Читать книгу Sang-Thong A Dance-Drama from Thailand - King Rama II - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

This translation and study of the background and present-day importance of Sang Thong have been done in an effort to discover in a literary work expressions of Thai views of life, and especially of views that offer some contrast with those of the West; to trace some of Sang Thong's motifs within the wider context of Southeast Asian and Indian patterns of thought; and to gain some insight into its dual historical development as it was gradually formulated by learned priests and refined courtiers, as well as by common, fun-loving villagers.

I have chosen for translation the dance-drama version of the Sang Thong story attributed to Phra Putthaloetla (King Rama II), the second king of the present Thai dynasty, who reigned in the early 19th century. This version is from Bot Lakhon Nok Ruam 6 Rueang: Phrarachaniphon Ratchakan II [Scripts for Six Dance-Dramas in the Style of Lakhon Nok, by King Rama II et al.], published in Bangkok by the National Library in 1958.

In an effort to retain as much of the subtlety of Thai thought as is possible in English, I have translated the first act, "The Birth of Prince Sang," line by line, with explanatory notes. Although these notes are at the back of the text, they are (unlike citations) an integral part of my effort in this translation to understand the Thai mind. Reflections of the Indian tradition in the characters and imagery of Sang Thong also appear in these notes. The remaining eight acts I have summarized with notes, again trying to preserve non-Western images and expressions reflecting values which historically or currently have been part of Thai life.

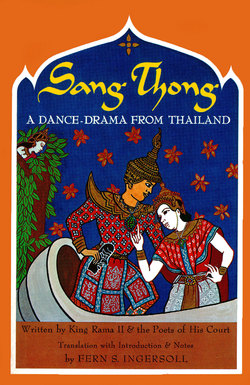

Illustrations for "The Birth of Prince Sang" were done by Bunson Sukhphun, who has lived all his life in the Thai rice village where our family lived for a year. He feels his court scenes lay no claim to period authenticity, but show what is in the minds of many country and city Thais when they recall the Sang Thong story. The country scenes illustrate in accurate detail the way of life during his boyhood some twenty years ago, which in many respects resembles rural life as it existed in the period of Rama II and as it continues even today.

ON TRANSLITERATION

Writing Thai words in Western script has, through the years, followed a variety of systems, no one of which is right for all purposes. I have basically followed the system recommended by the Library of Congress, which is not greatly different from that devised by the Royal Institute of Thailand. Stated briefly,

The vowels a, e, i, o, u are pronounced as in Italian.

th (as in Thai) sounds like t as in "top"

ph (as in Phanthurat) sounds like p as in "pin"

kh (as in lakhon) sounds like

k as in "king"

k (as in klon) sounds like g as in "go"

In the words Sang Thong, lakhon nok, and klon, the o has the sound of aw as in "dawn."

For students of linguistics or of the Thai language the system may be summarized in somewhat more detail:

| Voiced stops (initial position only) | b, d |

| Voiceless, unaspirated stops | p, t, ch, k |

| Voiceless, aspirated stops | ph, th, ch, kh |

| Voiceless spirants | f, s, h |

| Voiced nasals | m, n, ng |

| Front unrounded vowels | i, e, ae |

| Central unrounded vowels | ue, oe, a |

| Back rounded vowels | u, o, aw |

| Voiced semivowels—initial position | y, w |

| Voiced semivowels—final position | i, o (after a, ae) |

| w (after i) |

Except in the cases of Sang Thong, lakhon nok, and klon, mentioned above, which have previously appeared in English-language publications about Thai theater, I have used aw as in "dawn" to represent the third back-rounded vowel. I have also substituted likay, a form which appears in earlier English-language publications, for like.

I have used the conventional spelling for proper names.

For Pali words, I have used a generally accepted system of transliteration.