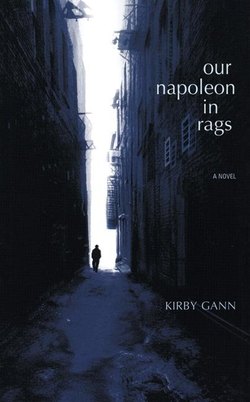

Читать книгу Our Napoleon in Rags - Kirby Gann - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTRAILING WINDMILL SAILS

THE NIGHTS AT THE DON QUIXOTE – that sumptuous dive – held darker than nights elsewhere, even if the club sat huddled within the smacked heart of the city. As in the rest of America (and for most Americans), this heart rarely became an object of attention and care, more fretted over than attended to, arteries hardening without complaint, a condition forming without the host’s knowledge. Like the biological heart, one remained aware but avoided the subject. One leaves the heart alone and hopes for the best.

We are in Old Towne, the broken-streetlight district in Montreux where dark house-stoops offer no welcome. Most of the light that sparked through the leaded wave windows of the Don Q was of the flashing variety, red and blue and sometimes white – vascular colors. The regulars called the Don Q the heart of Old Towne, thus making it the heart within the heart.

The original, stately farmhouse had once sat well outside city limits in 1865. As the decades passed it suffered add-ons and reconstruction to the point of invisibility, subsumed by brick. In our own time, the Don Quixote fell victim to the Come Back to Montreux! campaign, that brief resuscitation effort sponsored by the city council in the 1980s. They slashed mortgage rates in the vain effort to stave urban sprawl, inviting the wealthy to reinvest in squalid mansions left over from a more elegant era. Everyone believed Old Towne should have been the crown jewel to the city, a Dresden captured in amber glass on the muddy Ohio bank to lure tourists up from the Charleston and Savannah wastelands. But that support was arrested by a number of awful events, acts between the poor and dissolute confronted by the moneyed’s sudden interest, a history better left to sociologists studying the consequences of strikes, assaults, rapes, and murder. The campaign restored a few strewn blocks of eclectic architecture, but most of the homes remained arsoned-empty, or skinned by molding scaffolding, the hides of plastic sheets. What was left were hookers of all specialties and interests; adult bookstores barking private video booths; men in raincoats skipping over splashed glass in the streets, headed for the pawnshop brokers and liquor stores protected by pig-iron bars. And the Don Quixote, ferned and atriumed toward the glittering stars.

A wicket gate and garden path led to the entrance, crowned by a ragged windmill that was useless but for effect. Inside, the tiled floor swept down five quick stairs onto a mahogany and teak sunken bar. Above, in the original farmhouse, stretched the Theatre Room, where unsung playwrights presented works-inprogress, poets of the rant school sieged the stage for endless hours, and bands of every style played deep into the night. Though somewhat devout Christians, Beau and Glenda Stiles (the owners) still harbored bits of Bohemian soul.

Near the sunken bar there, under corroded lattice-work and paper lamps put up for sale by a Third World economic savior organization, Haycraft Keebler parlayed his days. As did Glenda and Beau, with their hapless helpmeet Mather Williams; as did the half-Cuban Romeo Díaz and his love Anantha Bliss, and even “our cop” Chesley Sutherland – all of whom own their places in this story, too.

Beau and Glenda provided the body the rest moved within, but Haycraft Keebler was the heart in the heart in the heart of this city. Or, to keep with the metaphor of the place, draw the group as a windmill with Hay the hub, the rest reaching sails – because Haycraft was the history of the place; his family blood was. His ancestors had settled the land and built the house, saw it lose the farm-field vistas as the old drive was first scarfed by dirt road, then cobblestones, then pavement, up to the day in Haycraft’s adolescence when corruption charges were leveled against his legendary father. The family sold the house and fled to Tennessee.

The celebrated mayor of Montreux in wartime, renowned for his string ties and classical learning, his passion for the arts and the planting of dogwoods; the holder of a congressional seat, who had been awarded a bronze statue in Frederick Park for his dedication to the progress of his community – Haycraft’s father Edmund Keebler expired before his family in a splash of his own vomit. Perhaps for this reason Haycraft became the crusader he was, seriously disturbed if unaccountably charming. Our bipolar bear, the regulars called him.

Whether keeping with his lithium or not, whether coherent in his rhetorical oratorios or else slurred manic to the point of raving, Haycraft believed in the agency of a long-gone Old Towne community, believed it with feverish religiosity, refusing to acknowledge that community’s extinction, recognizing however its dormancy. This conviction had forced him through a life of perpetual crises and La Manchian quests, of plangent hours sired by doubt and solitude. Yet throughout all difficulties Hay knew he could transform the world.

And on this night, the night when this story starts, he shouldered his satchel beneath the windmill and through the double doors with ardent certainty that the first baby steps toward that transformation were now taken, enacted in the sabotage of a public bus.

Haycraft had his own philosophy, his own methods.

—You are over twenty minutes late. I was beginning to worry, we were going to send Chesley out to look for you, cried Glenda at the sight of him.

Haycraft hurried to her with gracious smile and nodding head, waddling down the steps to the sunken bar with an ache in his back.

—No need at all, no need for worries, Glenda, I am perfectly fine. An evening of action. Resolving the question of character and fortitude and all of that.

He beamed into the face of the older woman, a face like a peach too ripe, swollen fat yet sunken in patches; a once-sweet face gone sour.

—You should tell me of all people if you’ve adjusted your schedule, Hay. I do have my own anxieties –

—Yes, Glenda, it was thoughtless of me. Just a touch behind. And of course you have your anxieties; here, let me give you a little something for your troubles.

Haycraft opened the withered flap of his oilcloth satchel and scrounged through one of the interior pockets. He cast a glance back up the stairs at Chesley Sutherland, who was a cop, a true working cop, although at the moment he was on leave pending an investigation of his behavior and was thus moonlighting as security for Beau and Glenda. Sutherland made a show of fiddling with the dials of his police scanner (an off-duty hobby, a way of keeping up with the trade), and Haycraft stole two blue pills from the satchel and handed them over the bar.

—You are a dear boy, Glenda said; she caressed his hand once and disappeared behind the swinging saloon doors that led to the kitchen behind the bar.

The row of regulars watched her leave. None of them offered comment. Her husband wiped down the teak of the counter with a damp hand towel as he set out a pint of English ale for Haycraft – his eyes, pouched in beer-gut pads, following Glenda until she was out of earshot.

—What will those do to her?

—A couple of smiles, nothing more, answered Haycraft. She will be calm tonight, my friend. No nagging for you; no agitation.

Haycraft knew agitation like an old friend; he knew anxiety the way the stable mind knows when it’s time to flee a scene. Rigorous schedules helped him maintain: the wristwatch looped through his belt gave specific measure to where he was in his timetable, pointing him also to where he should be without the allowance of delays. And Beau and Glenda knew that schedule well: three hours of meditative writing, three hours to canvass the Old Towne district registering voters (or taking action against the community’s latest outrage-in-common), thirty-five minutes for the tending of needs such as grocery shopping and basic grooming. Afterward he liked to pass one hour and fifteen minutes with the homeless men who played chess on the ironslat benches near the library, offering them bananas and squash, an assortment of nuts – Haycraft steered clear of the passionately colored foods, preferring the calm safety of earth tones. Each evening he proceeded in haste to the Don Quixote for his beer, his studies, and chance companionship.

He did not worry for work. Being dramatically bipolar and publicly registered as such, the government sent checks that he signed over to Beau Stiles, who acted as something of a guardian. The agreement being that Beau would hand over the money in increments (Haycraft could not fathom the responsibility of a bank account), ensuring that the fundamental expenses were covered first: rent, utilities, pharmaceuticals, et cetera. But Beau was a busy if good-hearted man, and more often than not he cashed the check at his own register and forked over one lump sum of bar-damp bills with the order Now Hay, don’t you go manic with all this in your pocket. Haycraft swore to a regimen of acute self-diligence; but – also more often than not – he would skip doses of medication (testing how long he could go without, when feeling well) and hit a spell before the cash found the landlord, or the gas and electric company, and a tip jar would appear at the corner of the bar with a strip of masking tape across the glass, HAY’S RENT inscribed in permanent marker. Beau covered the rest when he could. Beau said he never had cared to live as a rich man.

Haycraft remained aware of the debt he owed such charity.

—Beau Stiles, if and when I begin to play the lottery, and if I were ever to find myself reveling in the good fortune of such unlikely victory, you may rest assured you will receive my entire first year of deposit. I swear on that!

—We need two hundred K to get clear. Be sure to pick your numbers before the next full moon, we could both use health insurance.

Such loyalty originated in shared family history. As a young man Beau played bluegrass with Haycraft’s father – Beau on bass, Representative Keebler on fiddle – and he and Glenda had been there as bystanders when the connection to the race track was discovered, investigated, publicized, et cetera; they had watched sadly as the bright child Haycraft used to be developed into the strange soul the regulars knew. Beau felt some measure of responsibility for the tragedy, too, as he had led the retinue that brought Hay’s father to the horses.

He tried to look out for Edmund’s son, though it was not always easy. He had this place, a haven for the man, he would like to say; if he could, he would like to tell his old friend that his son was doing all right, that he was doing as best he could.

But the Don Q was not always the great refuge Beau hoped to create or Haycraft hoped to find. Hulking Chesley Sutherland eased down the stairs cradling his radio close to his cheek, the volume swept low to a bare crackle and burst.

—Yo Haycraft, you hear what I’m talking about? Bus crash tonight, four blocks down on Second. Guy pushes junk out in the street and wrecks a bus. Took out three parked cars and some lady.

—I can assure you I don’t know the first thing about it, Chesley. You said a lady? What do you mean, is she all right?

—They didn’t make a formal announcement. They got an ambulance there is what I know. What’ve you been up to? I notice you come up late.

—Leave him alone, said Romeo Díaz. Let the guy be, Sutherland, you’re not even on the force these days.

—Not today, no, but I will be again, you know. And I’ll have my eye on you, too, Díaz.

—Buses crash, officer, answered Romeo. It’s a tough world out there.

—Garbage doesn’t just fall into the street. Somebody put it there, they shoved it there. I think I know somebody.

—You don’t know anybody, man, you need me to tell you that?

Haycraft made a point of examining the yellow suds clinging to the insides of his pint glass.

—Yes, Haycraft said. Buses do crash all the time, don’t they? It is a dangerous neighborhood, you know. I think it a shame you are not allowed at the moment to keep us safe, Chesley; perhaps I’ll explore that in an upcoming editorial. All kinds of crazies running around.

The notion of becoming the subject of Keebler’s obscure essays did not impress Sutherland in the least.

—Yeah, your editorial. You put that in there, I’ll take it to my hearing.

—It could help! Discernible proof that the community stands behind you!

But this was said more as an aside, an afterthought. Haycraft’s head was already on to other things: After the day’s modest action, and the growing certainty that he may have gotten away with it, he could be forgiven the rush building inside him, his emotions insurgent and mutinous, the roilsome confidence that identified him (he felt certain) as a brash leader of men. This notion of “a lady” hurt – maybe even killed? – because of his actions was quickly morphing from an object of guilty fright to one of fateful purpose:

—I do hope your old woman is all right, of course. But maybe her misfortune is precisely what we need to inspire people to action. This district, what we need is a catalyst, Hay postulated. Something to fuse our determination, firm our resolve. A symbol, an icon, an issue to gather the many into one. A martyr.... Old Towne is a dangerous community, a community in danger; we need nothing less than a crusade. Crusades produce martyrs.

—We’ve had enough of martyrs here, Beau reminded Hay, curling a dry tongue over white-whiskered lips.

—Yes, but maybe this lady.... Haycraft trailed off.

He had no comeback; he knew Beau had it pegged: The two boys from St. Luke’s High School had created no catalyst to a saving crusade six years before. Instead they had started the engine behind Old Towne’s hastened decline. Lost one night on their way to a football game, they ended up in a discarded alleyway freezer – a block behind the Don Q in Huddle Gate Square – with trousers about their ankles, hands bound, one bullet wound each at the base of the skull. It had been Beau Stiles who found them. White suburban kids raped and murdered, killing too any further interest from investors. That the murderers were found at the investigation’s fever pitch, and were both black, unemployed, had previous violent records and contraband pasts the legal system had let slip through – locals, in other words – did nothing to encourage the moneyed public to find more to salvage there. Charming, once-lavish houses, yes; but little else. An area beyond salvation.

In his dark moments even Haycraft admitted that, for the most part, they were right. Still he said: All the more reason. All the more reason to try again. And yet again, if need be.

—Victory to the persevering, Romeo Díaz gave as a mocking toast. Haycraft, we need to get your candle dipped, man. We need to get you laid.

—You guys have all the plans, added Beau, casting the line out to everyone in a row at the bar, setting hacking cackles among the rank of men.

Romeo Díaz still held that sex was liberation; Haycraft knew the act would never erase the effect of Beau’s discovery that long-ago morning. That one of the murderers was also first cousin to Mather Williams provided endless fascination to Haycraft. By nature, fascination came easily to him: His soft lips fell into their curious fold, as of a horse’s mouth, loose, parted in rapt concentration, his eyes open and unblinking at whatever matter required his attention.

Glenda Stiles had made herself a kind of patron to Mather, a gentle but damaged soul, touched (people said), a man of general incapabilities. She called him a Child of God. Haycraft watched thin black Mather shuffle-muttering about the Don Quixote’s rooms in a swaybacked, knock-kneed gait, singing to himself, his mop standing in for a microphone. Hay observed Mather helping Glenda with prep work in the kitchen, the soft dark face lengthened in concentrated scowl, fleshy cheeks loose and shifting, his white server’s jacket – a leftover from one of Beau’s previous jobs – and black pants splattered with sauces, dips, cleaning agents. Haycraft would watch and ruminate aloud, wondering at what Mather knew about that murderous cousin, about what memories did the two share in common, and how did these affect him now – or did they affect him at all? Did the guy understand anything? He knew right from wrong; Mather was all about blessings. What does one make of having a murderer in the family? And when Mather finished his jobs and sat with his shift drink (brandy) on a corner stool at the bar, Haycraft ventured to ask.

—Mather, please, he began. Your cousin....

Except dear damaged Mather declined to talk about it. Maybe he couldn’t talk about it. Moments such as these caused Haycraft to lament that anything he wanted to understand succeeded in escaping him. Here is Mather listening: he leans his cauliflowered ear to Hay and his globular eyes spring wide; he tilts backward and shakes his head, says, No no no, uh-uh, or dismisses the conversation entirely: That boy bad from the day he born, we got the devil everywhere you know. He cackles a discomfiting, high-pitched crow’s laugh, rolling those gelato eyes, a sight people found disturbing before they realized his harmlessness. Mather’s eyes bulged large, the lids folded back to expose the entire egglike eyeball, glistening white and greasy wet. His teeth were yellowed and gnarled as though he had grown up gnawing bicycle chains. The mouth spread strung with spittle, the pink tongue withdrew as he laughed and laughed.

Haycraft could not find the answer directly, so he took the more roundabout method of examining Mather’s posterboard paintings, which dotted the walls throughout the building. Haycraft could spend as much as an hour in front of a single picture, savoring its forms and colors, reading the scrawled texts, absorbing the most minute of details. Primitive, yes; wildly oilstick colorful; splatched in scrawl – the works depicted a psyche lost to the cityscape. Crudely drawn corporate-logo galaxies (Marathon Oil, McDonald’s arches, Shell) spun in orbit about cartoon street signs, roadway markers, cars and buses, the occasional train. Scenes from the city set off-kilter, floating on the paper with no concern for perspective. Brooking these images ran rivers of prose, estuaries of free-associative diatribes and rivulet declarations, seemingly transcribed unedited from Mather’s head:

THIS is tHe MarATHon, you GoT to run run run to tHe MarATHon serMon of MatHer WilliaMs EvrYtHiNG MusT GO! sale. How abOUT tHaT MoNeY, brotHErs and SISterS? TeLL ME hoW BoUT SOME HELP? I taKe eAcH BOTtoM DoLLaR.

Mather scratched out the sentences in ballpoint pen or drugstore magic marker, lines aslant at whatever angle struck him as most convenient at the time of composition. And there among intersection road lights and vaguely figurative passersby, Mather designed advertisements for himself: SonGs For SALE / OnE DoLLAr I SING my oWN SonGs!!!

A list of titles with recommendations:

1) BathTub Blues – GOOD for winter sorrow

2) ruiNATION day – no child under 6

i mean 7 allowed, this SonG is SCARY

3)Them Dead Rat Blues

4)Somewhere Out on LonGStand RoAD

The last about when he got lost on the bus lines and ended up stranded in the county’s far east end. Haycraft paid a dollar to hear him sing that one, once.

Don Q regulars often stumbled across Mather at work, sitting on a street corner singing, surrounded by his art supplies as a child in a romper room, oblivious to the pedestrians and working girls altering paths to put more space around him. When not puttering about as help for Glenda, all Mather did was take the bus to city parts known and unknown. Whatever image caught his eye, whatever thought crossed his mind, made its way into his medium.

Haycraft inspected the works for a sign, a symbol, a clue he could use toward understanding. Chesley Sutherland confessed he could find nothing in them but the distortions of a raving mind. Romeo Díaz could expound on their value as relics of folk art – but the most real thing about Romeo was that he believed all art a sham, a con his nature allowed him in on the game of. Beau admired their energy, thought they proved the man had soul. And Haycraft agreed, arguing that even if the works could not be regarded as Fine Art headed for future museums, they still displayed a specific vitality. He pegged Mather as a kind of warped antenna, channeling the energy from the streets and setting down messages from the collective, communal spirit of place.

—Because you can see nothing contrived in them, he said. Nothing fabricated. They feel urgent and necessary, and what better definition of art can you devise on your own?

Once Mather finished his single brandy he said his farewells: a process that took a great deal of time. He repeated his farewells with a string of Thank you Glenda’s, and Were you happy with me today’s, and Do you want me back tomorrow’s, all to which Glenda gently responded with Yes, Mather, thank you too, we’ ll see you here tomorrow. It was ritual, perfected over years. He took her hand into both of his, delivered a smile and some speech; and then it was Mather walking two steps before turning again with the Were you happy with me today?, a hesitation as he listened to her assurances, and then again a few more steps away before he returned to see if he should come back tomorrow, back and forth, again and again. Only after he passed the luckless bar line of regulars did he say goodbye to each. He navigated the six steps from the sunken bar using an unpleasant seesaw movement with his hips, a walk that looked like he carried a great weight, as if he struggled to carry some object larger than himself. At the top he met Chesley Sutherland, who leaned into the exposedbrick wall with arms crossed over a once-banded, now meaty chest.

—And how are you today, my brother? A good day? Chesley answered only with a smirk and tip of his head.

—You keep breathing right, now, Mather added, gesturing at the asthma inhaler Sutherland clutched in one hand. You got to be strong, you got to be strong to be blessed, you know what I’m saying? Be blessed with a breathe-right night now.

Mather raised one hand in gentle beneficence as a gesture of goodbye-good will. Then, his eyes and jaw swooping over a long arc back to the others:

—You all have yourselves a blessed night now.

And off he went into the city evening, alone, to wherever it was he lived or hid, or to take his seat on one of the Montreux buses going anywhere.

With Mather gone and the click of the door stays fitting one another behind him, a settling descended over the rooms as the regulars relaxed into their long-haul night.

Capture this: Hoagy Carmichael whispers through the overhead speakers of the main parlor (one rests near Beau’s cracked stand-up bass, a holdover from his bluegrass days), its light piano lilting through “I Get Along Without You Very Well” as Romeo’s no-filters sift blue smoke about the pentagram paper lanterns; Romeo shifts in a single-breasted sport jacket, his benjamin overcoat thrown lightly over the bar and his Stacies propped on the stool next to him, all animated gesture and argument to Beau, who stands in rolled shirtsleeves pretending to listen. A clement smile graces Beau’s lips, he clutches a wash rag in one hand, and he directs his eyes to the baseball game on TV. Glenda murmurs the melody while she folds cloth napkins in contented lassitude, her floral smock reeking dusted with spices and sauce, her bobbed hair caught on one side in the arm of her eyeglasses; Chesley Sutherland sidles down the steps, rubbing the ginger stubble on his head and resituating the holster over his hip as he cranes around a post to catch the score. A few couples splay scattered and intent over their tables. Upstairs in the Theatre Room, the night’s band begins to check their levels, the drummer giving a shy punch to his kick.

Haycraft watches them. His lips part slightly, eyes saucer huge behind thick lenses, two fingers the size and texture of sausages holding his place in a fat book. He stares at the room and then the window, falling deep into the light outside as it grows fine as sand, whirling with red and blue, singing with descending sirens; soon that light filters to black, and the reflection of the bar in the glass stretches narrowly into the leaf-dusted, bottle-strewn boulevard. The illusion of the bar extending into the streets is definitive to Haycraft: All his efforts were focused on bringing the strangely patient camaraderie from inside the building out to spread over the neighborhood, and to bring the people from outside, in.

Capture this picture in a long slow dissolve, these few souls held static in their particular share of solitude. They offer singular visions of companionship to whomever happens along. A picture hesitant through the following hours, expectant, waiting for midnight to arrive like some longed-for music, waiting for each night to be stirred alive.

As the moon reaches its full height, the typical weirdness sets in:

No one could guess why a retired ballerina decided to discard her top and shimmy onto the half-wall that cleaved the bar from the rest of the room. Two AM and her shift finished at the Primrose Girls on the Go-Go, the Don Q parlor nearly crowded with sweating bikers and slumming bankers and career students ravished by their need to break from all things MOM – they shouted again and again for the bourbon and the beer that polished each leering face to a hazy shine.

Beau scurries to serve in Hawaiian shirt and black leather apron. He shouts to Romeo Díaz, No, no, tell her not here, this is a good place! and allows himself a good take on her bare torso before casting a glance for any glimpse of wife Glenda nearby; at no sign of her, he hacks a grateful guffaw.

Romeo turns to the young woman to pass on Beau’s orders, but stops speechless at the marvel of her bare breasts, sculpted scoops of pale flesh peaked by a maraschino cherry rose. She drifts through a drunken routine of pliés and jètés, culminating with a turned ankle, a surprised exclamation, her bruised bottom scattering dirty glasses from a nearby tray.

She sits in silent rumination, gazes at the floor with a confounded smile. As if alone in her bedroom she reaches to her left breast and scratches the underside softly.

—Buy her whatever she’s drinking, a shirtless man in leather jacket, HELLZAPOPPIN emblazoned across the shoulders, waves to Beau. He mocks applause for the performance, shouts his thanks.

—Well what the fuck is that? asks his companion, twentythree clutching at forty with handbag-leather cheeks and blue smudges beneath her eyes. Smoke frets from her mouth and over his face though she appears to be griping to an invisible associate beside her, loud enough for HELLZAPOPPIN to hear. He fiddles with one of the tiny rubber bands spindling the braids in his beard.

—Let it hang, woman, he answers her.

She sucks harder on her cigarette and hot-boxes it, the yellow of her eyes rimmed with venom. He looks at her, looks away, smacks his lips at something distasteful, looks at her again:

—Don’t break my balls over it, jesus, I’ll slap you here to Nashville, he adds, and this breaks her gaze.

Díaz approaches the dancer, fresh gin rickey on HELLZAPOPPIN’s tab in hand for her. He drapes his jacket over her small, bare shoulders; her top seems to have disappeared. Beau checks Chesley Sutherland, who scowls and shakes his head, setting Beau to wonder if he should expect a crackdown soon – he worries that Chesley, under investigation with another cop for his second excessive-force complaint, might decide tipping off a fruitful bust could help his case with the department. Then again, Chesley still wears his gun, which can’t be legal in his situation. On such unadmitted bargaining chips Chesley and Beau have built a solid working relationship.

A pack of redneck southenders stride down the six steps from the Theatre Room, exulting in the nostalgia of classic-rock covers going on in there. Swine-eyed with liquor and scavenging for more, a brush-cut boy in Hilfiger attire continues to a buddy:

—I says fuck you officer, pulling me over on expired tags, I mean I was only two days late dawg. . . .

Sutherland shadows them near the bar, hoping for a messy altercation. He turns away to suck on his inhaler and misses an underage patron maundering the tables for unclaimed tips.

The clock pops to three, Saturday night’s heaviest hour. Romeo is launching into grins now as he makes clear headway with the ballet dancer.

—It was $225 a week with the company, I only got corps work, she says, one slender hand modestly pinching together the lapels of his jacket. I make that a night now. Exotic dancers have longer careers, too.

—You are absolutely right, Romeo agrees.

She opens the jacket and lifts a breast to show him a pink scar from where she had paid to have a size reduction to meet the demand of an art she later abandoned. Now she was saving to have them enlarged.

—More money in a bigger size, she says, and again, Romeo, fascinated, replies:

—You are absolutely right.

The dancer appears now to fully observe Romeo for the first time, to actually consider him as a real person and not a vague figure from a daydream, and the first hint of a smile tightens the soft corners of her mouth. She offers him her hand and says:

—Anantha. Anantha Bliss.

—What kind of name is that? Anantha Bliss?

—Not my real one.

Romeo’s grin moves beyond his usual leer, and he takes her hand between both palms and raises all three hands together, a gentler version of his gentlemen’s handshake. He has no idea what sort of transformation has just been introduced into his life, and as yet feels overwhelmingly confident.

Son of a bitch !

Those circled nearby turn and look; the corn-yellow teeth of HELLZAPOPPIN’s companion are bared in response to an unanticipated slap. He was feeling his whisky. Magically a compact mirror appears in hand and she adjusts herself accordingly, inspects her face for visible damage. Finding nothing permanent, she sneers at those who stare: What’re you looking at?

On a run to the bathroom Romeo stops long enough to scoff at Sutherland’s dutiful public stance (arms crossed over massive chest, feet shoulder-width apart, an air of smug alertness though his eyes appear aimed above the crowd at the far wall). He expresses sympathy for Sutherland’s frustrations at being allowed only to watch.

—Big healthy boy like you and nothing to do but spectate? And we got crimes going down right now all over the neighborhood, some damsel in distress you can’t do anything about!

Sutherland shoots a sullen stare. Since his suspension he has muttered this outrage often – that while he wastes time among the drunks at the Don Quixote there are real crimes being committed throughout the district. Like today’s bus accident. What if a cop had been out there on a beat? The injustice just baffles him. But he doesn’t mind a little play here and there with Díaz, and he refuses to take the bait the man has tossed him. He suggests Romeo had better be careful not to take too much time with the young boys in the bathroom, he might lose his girl to an off-duty cop.

—Off-duty is what you call it? Romeo laughs.

Sutherland ignores the question, happy with his picture of Romeo in action in the bathroom stalls.

—You probably wouldn’t care about losing the girl if it meant you got to keep the boys, would you Díaz? he asks.

—Only man to suck me off was a cop like you. Except he was working.

The exchange heats quickly between these two men who never liked one another and never pretended to. Sutherland follows Romeo into the bathroom (the two stalls empty), questioning aloud Romeo’s problems with authority, his macho spic bravado, his loneliness.

Back in the parlor Beau listens to their yelling and shakes his head, shrugs.

—I’m tired, he tells Glenda. Honestly I don’t know how much longer I can stand this shit, it gets harder every night.

One hears such declarations from Beau on a regular basis.

Sparks ignite between HELLZAPOPPIN and his girlfriend, trading half-slaps and hard poking fingers as their companions scoot their chairs from the table with a weary, accustomed air. Haycraft, nearby and alone among it all deep in a book, raises his head and exclaims, People, please! but they ignore him. He scans unsuccessfully for Chesley Sutherland. Beau is of no help, either, a frantic blur behind the bar now as the redneck boys high-five one another, backing hard into other guests.

HELLZAPOPPIN clutches his girlfriend’s hair in his fist, and Haycraft raises to his full height. Dear people, I insist, he begins, just as Romeo stumbles rumple-shirted down the steps to the bar, shouting that he wants Beau’s aluminum baseball bat. The dancer smiles and rolls her neck on her shoulders, the jacket falling open. She is leaving. Sutherland smiles to her as he gambols out of the bathroom beaming, sliding a raw-ham hand over his stubbled head. He is bumped shoulder to shoulder by a man skipping out on his tip, a surprise so impudent and unthinkable that Chesley can only stand still and watch him follow Anantha Bliss out the door. And at the height of it all slings the wild clanging of a brass bell, Beau’s hand desperately yanking the hammer rope, and the tension washes up in the air with the ceiling fans, vanishing into Beau’s punchline cheer: Time to tilt at the windmills, folks!

Outside it is morning. The night is now over, its teeth marks still scraped across the sky.