Читать книгу Our Napoleon in Rags - Kirby Gann - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHAYCRAH KEEBLER, HUMMING

HAYCRAFT AWOKE BEFORE NOON and fried up a breakfast platter of potatoes on a crusty hotplate, adding apple juice in a fogged wine glass culled from the clean side of a steel sink. As he took his breakfast Haycraft fetched his thoughts, hopeful it would be one of those fugitive hours when the thoughts would come. He considered himself “a man of dialogue,” citing Plato’s discourses as the prime example, and in these mornings the dialogues took place within himself – or at least by himself, in that he ranted around the cramped room, index finger pointed and raised, or hands turned out in muddled exasperation, head shaking as he voiced a multitude of questions (one giving rise to another) and, less often, answers to them.

Several points of view clamored in his head; he believed his particular genius lay in that he allowed himself to hear out each one. He often referred to his mind as the House of Representatives. If the dialogues would not come, he forced them to the surface via another fastidious protocol, his single obsessive hygienic rite: trimming his toenails. Haycraft Keebler had large feet with nails of maniacal growth. They required constant trimming and shaping, or else turned ingrown and disturbed his canvassing ambitions. He believed healthy feet formed the man: If the feet are distressed, then so the soul. Cryptically, he quoted Emerson: We see with the feet. Somehow this action with the clippers and file opened his inspirational well, acting as sergeant-at-arms to call his House to order.

After soaking one foot at a time in a large steel mixing bowl filled with steaming, salted water, Hay positioned himself on the single chair in his room, an old elementary-school chair with adjustable pressboard desk, which he reconciled so that one heavy foot rested upon it within his vision and also before the long double-hung window that gave onto the wide avenue outside. Snip-snip and click, then turning the file to smooth the newly exposed ridge, always perfecting each toe in turn rather than the sweeping gesture of cutting all nails across the foot before starting over again with the file. Murmuring as he worked: It’s in the details, boys, always in the tiniest details . . . until the words fell way to a melodious hum of Stephen Foster or Broadway standards. He did not bother with the rinds spun onto the floor. His eyes centered upon the window and the street scene outside, or else the curtain of his mind’s eye opened upon a loaded memory: an old woman pushing her belongings in a grocery cart rendered ruminations on why the city had a home for battered women but no shelter for the homeless specific to women (their nightly risks must be enormous!); an eight-year-old running about midday underscored the result of budgetary cuts from the truancy division of the police force; two men scrubbing away the spray-painted faggots from their doorway inspired his most high-profile success of helping usher through a fairness ordinance through the Board of Aldermen. Or, if not actually ushering that ordinance, he had at least helped in bringing the matter to some attention.

Everyone had a hard road, Haycraft knew. But you have to start with the small, concrete details. Can’t afford the broad gestures of historical perspectives – because that makes a question all or nothing, and absolute failure is not a possibility you can afford to entertain. His father used to tell him that. His father, whom Hay remembered as an amalgam of Thomas Jefferson, Merlin, and the apostle Paul.

So Haycraft concerned himself with general issues but strained toward specific, practical steps. What bothered Hay in general was the disappearing middle class, the widening gap between the very rich and the very poor. He also found the local police force unnecessarily brutal and intimidating. In moments of lucidity he realized there was little he could do about these aside from pointing out the obvious to those who could hear him, and he accepted as likely that his commitment to these issues was mere cover to a deeper loneliness inside himself. . . . Alone and obscure, he responded by loving everyone in the abstract. But what bothered him in particular, in the details of daily life (and therefore actionable), was the debris that saturated Old Towne like a wild fungus ravaging a tropical village: He could see it from his school chair by the window, he stepped over it any time his schedule thrust him into the streets – the discarded junk, cars on cement blocks, engines in the alleyways, carpentry materials, old roof tiles, gutted fixtures and cracked moldings and furniture, asbestos lining, and refrigerators with stillattached doors ready to coffin some unsuspecting playful child. All this and more, uncollected. Here, in the district that displayed awesome examples of America’s domestic architecture. Such sights wore on Haycraft; they inspired him. It was all going to change. Forcing a public bus to crash was merely an initial, active step.

Perhaps too firm of a step. He did hope the lady he had heard about was all right. He had been looking for an evocative statement, not an act of terror; he was an idea man.

Such ideas found their way into the broadside newsletter that he wrote, typed, edited, printed, and distributed himself: The Old Towne Fair Dealer, on-time delivery of which he guaranteed and accomplished along with his voter registration routes, the words of the newsletter gaining an extra air of authority through their proximity to official documents. Other copies made their way under the windshield wipers of parked cars or met pedestrians face-to-face from telephone poles, or skittered down the street on the wind, clinging to pantlegs.

—Madam, would you care to take a moment to learn of our mayoral race and its dire implications on the course of your life, he would say to a scrawny figure in giant sports T-shirt and curls, clutching one infant and flanked on either side by wide-eyed and silent dirty-faced urchins, figures from Dickens transported to the city Hay had taken upon himself to redeem.

Grasping the mother’s attention, he launched into his most laden rhetoric – a style ingrained from his father’s campaigning days, when Haycraft himself had been the plump-cheeked child clutching the trouser leg, the difference being that this leg had been clothed in worsted wool, and that Hay’s face as a child had been clean, spit-shined by his mother’s kerchief, his hair brilliantined, his teeth white, his tongue stinging from a drop of cachou. His discourse threatened unholy annihilation by the indifferent powers-that-be of the lowly citizen doing her best to make ends meet. Once this fear had been staked precisely in heart, Hay’s Fair Dealer appeared among the registration forms – forms he filled out himself in order to trouble the potential voter as little as possible, asking for signature only, sometimes signing for them beside their X.

UTILITY CREWS IGNORE OLD TOWNE STORM DAMAGE. PLASTICS TOOL & DIE: CITY ATTEMPT TO POISON OUR CHILDREN? From declining library funds to sewage anxieties to the rise in teenage prostitution and the latest police brutality; from calls for a civil review board to the syringe recycling program, Haycraft’s House of Representatives covered them all. Smothered and covered them all, he liked to say, with each article subtly steeped in his avowed subtext, his final goal: nothing less than full secession of the district from the city of Montreux. Old Towne as autonomous community. Haycraft Keebler, political philosopher and populist idealist, manic-depressive man-abouttown, was a secretly subversive character.

And who could not believe him? Who in such a lost and forlorn community could not be left with the suspicion that this charismatic and feverish man at the doorstep was not on to something?

Away with apathy! he shouted, striding through the alleyways. You are not so content! If our souls are on their knees, then let us bleach clean the pavement! Haycraft believed the people’s indifference only masked their fear, and that this fear was little more than a child’s staring at a lake, not yet knowing how to swim.

He embodied enough outward signs of the kook to prove convincing: ski cap in summer, pin-striped trousers held by buckled suspenders; massive feet bursting at the seams of plastic sandals – sandals he vehemently defended as necessity, for their massaging fibers allowed his head to remain clear and focused, and his odd widths and low arches made it difficult to find good, proper-fitting shoes. A polo shirt buttoned to the neck still could not hide the splash of hair graying over the collar, curling to the loose, stippled skin of the neck and chin, scarred with red streaks from years of poorly prepared shaving (he shaved using the same steel bowl where he soaked his feet, and prepared his skin with a bar of castile soap). Clean-cut but cursed with oily hair, all sixfeet-two and 220 pounds of him rooted in your doorway, the glint of passion in reserve cornering his eyes and you, tired from a hangover that has lasted into its third day or jonesing hard for a cigarette since you swore to quit (or at least cut back) instead of paying that new tax of seventy-five cents per pack, sickly full with beans and eggs for the umpteenth time, anxious over your station in life or else not giving a shit at all – your lack of a job or even direction crushing your blunted senses, and what’s this you hear about your benefits being cut off soon, and why won’t the kids shut up, and was that neighbor boy in the stolen SUV backed onto a fence post really trying to run over those police officers so that they had to shoot and kill him with sixty-four rounds? – and you, weighted with this day of your life in arrears, find this strangely focused but intensely assuring bear of a man in your doorway, unbidden, telling you that with the least bit of effort on your own part, with support from himself and his streamlined network of volunteer agents, this life of yours can change. For the better. For the problems you face are not yours alone, but the entire community’s. And that community is ready to act. All you have to do is sign here (or allow him to sign for you), join this mailing list, perhaps answer your phone if you have one. Endeavors will soon be undertaken.

Why not? What do you have to lose? He’s not preaching the glories of freshly minted religion; he’s not even asking for a handout. Here was a man with a mouth perpetually formed to say yes. Here was a man who spoke of practicalities. And he wanted to do all the work himself. Why not?

Naturally not everyone was pleased to find hulking Keebler at the stoop of their home. Those who lived in the few blocks of restored mansions (trapped, like Beau and Glenda, by the Come Back to Montreux! campaign) could do without him. Desperately hip young lawyers and fund-for-the-arts economic developers and anti-Freudian existential psychoanalysts and the entire fey interior-design fetishists crowd preferred to keep to themselves behind gilded walls and sculpted cornices, protected by brick and iron barriers. Haycraft could not access many of them due to the elaborate security systems at their gates; others owned vicious canine defenders, an animal Haycraft held a nearly superstitious fear of. So he steered clear of these homes by habit (discreetly rolling a copy of his broadside and dropping it through the iron bars), although he was not afraid to approach these owners for brief recruitment talks should he find them offhand some evening in the Don Q, dining on one of Glenda’s homemade spanikopitas or drop biscuits. But Beau did not want Haycraft pestering the ostensibly well-heeled patrons, that sacred few. Credit-card charges zoomed directly to his bank account, but the ratio between checks cleared and checks written was always a precarious one for the Stileses.

It was the lower castes of the Old Towne citizenry that gave Hay his heroic impulses and adamant fervor; they were the ones who most needed the catalytic spark, the symbol of some martyr.... The educated near-rich he held no sway with and knew it – he approached their doors out of a sense of duty, not confidence; he stuttered and fretted and accomplished little if someone answered their door to his surprise. But The Lost, as he called them, inspired his obstinacy. With them he sought connection. The Lost had been his father’s territory – to his father the lost and the local amounted to one and the same thing. All politics is local, and the locals is lost, he had liked to smirk when playing at his homespun manner, often, to his young son. So it was not beyond the realms of possibility that when Haycraft crossed paths with a particularly fragile soul, he might see the meeting as nothing less than the end of his solitary ways. A savior’s life is a lonely one.

Haycraft came marching past empty playgrounds and vacant lots through a warren of rookeries, full of himself for having signed a new subscriber to his newsletter, a silk-hatted young man in a T-shirt inscribed with the maxim TATTOOS WILL GET YOU LAID. They had agreed that if his secession plans succeeded then Hay could promise the young man a place in his cabinet, or at least a position in the cabal or shadow government he expected to organize to unofficially run things. On that glorious October day of ecstatic light sinking on the crisping leaves and cigarette butts he crushed under sandaled feet, shreds of burnt tobacco streaking behind his heels, Haycraft hurried to stay on schedule (the modest summit meeting had forced an extension to his allotted hours), until he was struck still with the same intensity as Jesus realizing sight of his first disciple.

Lambret Dellinger was the vision. Just a boy, fifteen and spindly thin beneath a white cotton Tee and faded black jeans, a pair of scruffy Doc Martens lifted from a thrift store covering his feet. He sat huddled beneath the glass wicket in the back gate at the Don Quixote, where the alley gave way to a stone garden Glenda tended, fenced in by fraying, treated wood. His hair was so black it appeared nearly blue in the shade, spiraling coils falling over his dark brown eyes and soft pale cheeks that were each rouged by the coming evening chill. He had never shaven, had never needed to. He sat with his back to the fence, arms crossed over the knees, chin on wrists, eyes staring blankly through waves of sheened hair. Absently he rolled a length of iron pipe back and forth along the length of his foot, the metal singing a sharp note about him. The stink of the city sifted in the alley breeze.

Haycraft, unaccountably bereft, beheld him. So taken by the sight he did not even notice car parts freshly dumped the length of the alleyway, nor the rolled chain-link fencing coiled against the curb. He shifted his satchel higher on his shoulder, transposed his weight from one hip to another. It was no good, he could not speak. He moved the satchel from right shoulder to left, waiting, his mind an empty slate, his eyes enlarging at the prospect of the boy – a mere wastrel! – descried there, he felt certain, as a sign: a sign for Haycraft only. Alone and bursting with youthful life – the violet splotches beneath his eyes notwithstanding, nor the stink of the rag soaked with mineral spirits drying between his wrists – a portrait of raw elegance in repose. His hair, wild and abundant, fell in thick locks over a surprisingly serene forehead. Surely the boy knew Haycraft was there, gazing haplessly. Why didn’t he say something? Then again, why didn’t Haycraft speak? For hours each day, unrestrained speech sprung from Hay’s tongue to total strangers. Now it was no good. His thoughts crossed and recrossed and crisscrossed the paths of his mind, retracing his history of ebullient and confident conversation, his witticisms, his implications, his clever asides and jocularities. He found little help. Only one offering came to his veering mind:

—Hello? Haycraft asked.

Met with silence. The autumn breeze came again, more forcefully now, shushing wrappers along the cracked tar and unmoored cobblestones; the sun’s brassy light pulled along the backs of the houses with it. The boy stared straight ahead, his limp gaze fogged in such unusual light, vaporous, lacking focus. The metal pipe sung out its single steely pitch.

—Hello? Haycraft asked again, emboldened by the boy’s silence, as though such silence suggested vulnerability, a plea for aid. This time his voice registered on the boy’s face; the heavy eyelids blinked slowly, the head moved with a deliberate and indulgent roll of the neck. His round cherub’s chin lifted briefly from his arms. The rag fell free to the ground then, presenting Hay with the only blemish to that perfect face: a cloud of raw, pink skin flamed about the mouth. The boy lay his head back against the wood planks behind him, lazily – demurely, Haycraft would describe it later – and the eyes, glowing with a micalike shine, took the man in.

—Hello boy, Haycraft said yet again, a final time.

The boy answered with his own hello, after a good long pause, apparently forced to go some lengths in search of the word.

He speaks! bellowed Hay. The words came rushing then. Such a handsome and able-bodied young boy, Haycraft said, and here he sits alone? Why, did you have a fight with the parents? I’m not sure I understand what you mean by no parents. Everyone must come from someone, I don’t believe things have changed that much since I was your age. How difficult the young must have it these days if what you tell me is so. What do you mean, you are working? But working how, crouched like this in one of our unfortunate alleyways, when it should be the world crouched before you, crouched at your feet! No, I do not lie! Tell me, have you eaten? Would you like me to give you, boy, something to eat?

Lambret sneered, he mumbled almost incoherently in a soft and broken voice; it would cost the man twenty-five dollars.

Such an exchange made no sense to Haycraft.

—What’s that? You would charge me for the gift of giving you nourishment?

The boy’s eyes crimped as though taken in sudden headache. The chin fell firmly down to his arms again. He worked his lips between his teeth, stretching the irritated skin around them.

—Come on now, I don’t have the entire evening. I am behind schedule as it is, and you see it is very important to stick to a plan as it was designed, mmmhmmm. Let’s get you a good cheeseburger. Glenda makes the best in town and uses only the leanest meat available and buys only from farmers who do not employ growth hormones, and with his hand reaching from beneath the satchelled shoulder he waited. He waited, and wondered, looking over the boy, thinking What have I found here, just look at the sight of him, a prince unanointed, as Lambret asked if a cheeseburger was really all he wanted to give him, his eyes gathering focus now. He took to his feet slowly, slovenly. He admitted he could stand something to eat all right.

All thoughts of The People and The Lost, of land co-ops and entrepreneurship programs and the need to beautify these alleys and to draw patrons to the pleasures of the Don Quixote, disappeared before the prospect of the boy Lambret Dellinger. It would be getting to night soon – Hay could feel the shifting hour like the edge of a blade to his ribs – and there Haycraft was, stuck outside, and so far off schedule that he was humming again, his first hint of agitation. The lengths of his nerves fluttered alive with hummingbird wings. Usually a case of worry. Yet the Don Q was only a few steps away, and twilight had arrived – the hour that always led him to recall the Tennessee farm his family had fled to; when the peacocks leapt to the low branches and screeched their mournful cries; when Haycraft had no concerns further than finishing the nearest book at hand, and arriving home in time for dinner, and the parlor games invented by his parents. It would be night soon, yes, which meant time to allow the day’s duties to slide into memory and to relax one’s wayworn body among fellow strivers and comrades. The nights at the Don Quixote always did evoke in Haycraft the feeling of a reward bestowed.

—Look what I’ve found, Haycraft announced to the regulars upon entry, setting down his satchel on his corner table before approaching an open barstool nearby. A new friend recruited to our aid, plucked right off the street. And hungry, too.

Beau Stiles smiled down to the curiously young face. No doubt he made up his mind in that instant as to Lambret’s condition, station, and the level of surveillance he would require. Beau had the gift of making snap judgments of character while his face betrayed nothing more than considerate attention. He moved the tip jar marked HAY’S RENT outside of Lambret’s reach as he asked the boy what he might like to eat.

—One of Glenda’s famous cheeseburgers, Haycraft said. I promised him already.

The rest of the regulars offered a cautious welcoming as a family takes in a stray dog, undecided on whether it could stay for fear it might be rabid, dying, or belong to someone else. They were willing to keep it fed for the moment, willing to grant the stray a pat on the head. Haycraft had invited in The Lost before. Usually these were yammering bag ladies of the grocery-cart variety, rag-arrayed beneath plastic head covers, the dour and dowdy aged who swooned in sleep at the comfort of a booth and whistled through piano-board mouths, leaving Beau and Glenda to wonder what to do.

Lambret didn’t mind the new faces, the interior decor strangely foreign and otherworldly (all that stained wood, the palms and brick, the hanging paper lamps) filtering through the easy fumes in his head. Happy chance had placed him there, though once darkness fell fully over the city with its shroud of safety, he would need to slide out onto the streets again to Frederick Park. But that would be later. A boy on his own: Lambret was in no position to complain about any help he might stumble upon.

The adults observed Lambret closely, searching for clues in whether he ate his fries by hand or by fork (he ate them by hand), and with what manner he approached the cheeseburger. Lambret tore at the sandwich; he ate with a voracious appetite. That pleased Glenda, who prepared all the food from scratch, using her mother’s basic recipes and channeling her father’s improvisatory panache to make the dishes her own. She was especially proud of her cheese-and-garlic-crammed drop biscuits, and was happy to see that she did not have to force the boy to try them. Moreover, she had not seen her own son since he left for college on a partial scholarship in drama nearly a year before, and so was gratified to speak with a boy not too far from his age. For the recognition; for the memories of her own house once filled with all kinds of loud, rumbustious teenage boys.

The over-twenty-one policy didn’t take hold until nine o’clock. As Lambret sucked down soda after soda, Glenda plied him with questions about schoolwork and family, questions he evaded with shrugs and the phrases it’s okay and they’re all right, evasions that did not bother her (he was a teenager after all), as his silences allowed her to relate stories of her own son, Damon, and the letters he wrote home from Texas, and her worries over the loans he had taken to get by in such a large state as Texas, she said; how could a drama major ever expect to pay off his loans?

—Something about being a Stiles, we’re just built for debt I guess, she fussed, gesturing at the bird’s-eye maple wood trim on the backbar, the mahogany of the bar itself.

—But he does love his education, she continued. At least he does now. I wonder how he’ll feel when the bills come due and he’s working steakhouse theater.

—Or a girl turns his head, Beau added, smiling.

Glenda laughed with delight. It was a shared joke having to do with their own history, though they never let the regulars in on the exact reference.

—He never responds to my letters, grumbled Haycraft.

—You don’t write him letters, Hay, you send off your newsletters, Glenda answered.

—Yet each is a personal missive from me, directed to any individual whose eyes might grace my four humble pages. My thoughts and observations, things I want the boy to respond to! Simply because I don’t scribble Dear Damon at the top or sign off with my fondest wishes doesn’t mean I don’t want to hear from him. It is important – of utmost importance – to stay in touch with the views of the young. To nurture. They have a much clearer perspective on our society than we, who are hopelessly enmeshed within it....

Maybe such proclamations best accounted for Haycraft’s initial attachment to Lambret: the man’s desire to stay in touch with the young. Many times before he had voiced his attraction to all things of energy and beauty, and despite a sulky temperament under the influence of inhalants, the boy provided a good deal of both. Once the effects of his habit wore off, Lambret was bright, questioning, the eyes no longer glazed, but large and curious. He showed a compassionate heart in caring for a number of stray dogs collected from the neighborhood, sheltering them in the wreck of an abandoned house off one back alley, nursing the injured ones – such as Blind Mooch, who had been blinded by a rat – back to health. He played crate basketball with other kids, or else sat out the midnight hours with a spray can in hand to sketch his tag on any surface he deemed appropriate.

But for money he worked a walk in Frederick Park, the shuffle line of urgent, shadowy men who crept past the statue of Haycraft’s father with one hand on their money. Any one of them there at the bar could guess at what he did on first sight: The initial glance required a doubletake to clarify whether he was boy or girl. He appeared to be in-between. Despite soft features, his face betrayed a lean hardness advanced for someone so young – it betrayed a life accustomed to sleeping in the odd spot, the dark stairwell or dried culvert, his face. Haycraft seemed happy, but what could a hustling boy want from him that was any good? When the two arrived again at the exact same time the next evening, suggesting the youth was not going to disappear at once (that Haycraft’s schedule had made a minute adjustment), the conclusion was apparent on the face of each one there: They would have to keep an eye on this Lambret kid. Haycraft was one of their own, after all.

There was nothing suspicious to find in their attachment, in Hay’s point of view. Haycraft gave, so it was only natural that in turn he should attract a trustworthy, giving companion. And Lambret was as different from the other night-boys working the park as the drawing of a tree is different from a real one. They forged a bond partly on Lambret’s love of graffiti – or, more precisely, his knowledge of and intimacy with the usefulness of spray paint and its variety of possible applications. Lambret could sing a rhapsody to the glories of spray paint, the pleasure found in the hiss of aerosol, the rattle of the ball in a quivered can, the comfortable fit to the grip of his hand, the satisfaction of instant surface transformation. Sensing a poetic strain in the boy for the first time, Haycraft encouraged him to describe his passion further; and, listening closely, head angled backward as he scratched softly at the raw flesh of his shaved neck, Hay’s House of Representatives was called to order, wherein a lively debate commenced.

Because the contrivance of a bus wreck was not enough. Executed perfectly, it achieved nothing more than two newspaper articles detailing the event, and one self-righteous editorial condemning the sick minds of a few obscene souls. (A complete misreading, in Hay’s view.) It turned out the woman he’d heard of had been only grazed by the fender, causing a few scrapes and bruises. The city hauled away the debris that caused the accident, and the event disappeared. The rest of Old Towne still suffered its crisis of uncollected refuse, especially in the forgotten alleyways – those passages Haycraft and Lambret both knew with the familiarity of lovers.

The city rarely flagged in regular collection of bagged trash; outside of the odd strike here and there by put-upon workers, curbside pickup occurred every Thursday. No, the crisis lay in the larger objects, the materials discarded by bankrupt manufacturers, tobacco rollers, abandoned construction sites, the fled well-to-do: culvert pipes, random iron and metal scrap, ancient air conditioners and ovens, railroad materials left over from the historic Nashville line (which cleaved the district, but not as definitively as the affluent would have preferred). Even distaffed telephone poles remained strewn over the original paving stones, clogging the narrow passages that Haycraft utilized in his canvassing endeavors; passages that Lambret and his pals used as escape routes from the likes of the Chesley Sutherlands out there who were not serving suspension-with-pay. Lambret and his pals were large-scale graphomaniacs, surmised Haycraft. Trick money in hand (or, more commonly, with the discount secured by a jacket of ample pockets), they cleared the hardware stores of acrylic spray paint and permanent markers and then covered storefront security gates and streetlevel power boxes, public telephones, bus stands, concrete viaducts, newspaper dispensers – any workable surface on which a kid could stamp his tag. What was left in the cans and markers flowed through the boys’ nasal passages, a practice Haycraft abhorred instinctively, disgusted by the sight of their soft mouths circled by inflamed haloes, peppered acne, flakes of paint. He went about them thrusting his handkerchief to their faces, often spitting into the cloth first like a mother scrubbing her child on the steps before church. A practice that set off the boys into bursts of embarrassed laughter. A sound Hay liked.

But first things first: At this time Haycraft was much more concerned with the graffiti the boys practiced than with their health. Before Lambret, he thought the wild looping caricatures and obscure tags an irritant to the urban eye; but once he had met, and watched, and listened to Lambret passing time with his friends, throwing bones or watching the dogs wander through empty lots, he grasped graffiti as possibility. With Lambret in mind, the unintelligible scrawls became not a further junking of civic culture but a legitimate form of underground expression. If nothing else (Hay maintained to Beau and the scattered regulars at the sunken bar, over several wet autumn days), the images brought attention to those objects usually ignored.

—A power box; the back of a stop sign. It’s as though you’ve never seen them before. Suddenly there they are, singular and credible, worthy of scrutiny.

Romeo Díaz snorted at what he considered to be another in a long line of Hay’s “inane” campaigns – crusades he believed came only to a man who had the leisure to imagine them and who, he would say, approached reality at the most present angle of convenience. He toasted Haycraft’s new insight with Dewar’s and soda; he asked Hay if the kid had introduced him yet to the aerosol can’s other recreational uses. But the notion of graffiti as environmental enhancement outraged Chesley Sutherland.

—There’s nothing singular about it! Incredible is the only word I have for the contempt these kids show – it’s arrogance pure and simple, covering our public works like kudzu. They are defacing public property, Hay, doesn’t that bother you?

Chesley had his ideas, too; Sutherland’s Laws, they called them. He preferred “The Sutherland View.” If you want to hear the Sutherland View on the problem, he might begin, entering a conversation on capital punishment, I say you dust off the chair and plug it back in. His main tenet being that actions against his sense of the public good must be met with an opposite and overwhelming reaction, for example, any kid caught at the bus station with spray can in hand should be prosecuted to the full extent of the law.

—We don’t have much to punish them with, he admitted. But watch your pennies and the dollars will take care of themselves. Hit the kids hard for misdemeanors and then it’s easier to nail them later at the felony level. ’Cause trash always comes back. Get them locked away soon and you never have to worry about them again.

Haycraft rarely digested the opposing thoughts of others. Usually disagreements led only to his further fastening of mind. The work of Lambret’s cronies had raised Hay’s awareness; innocuous objects no longer escaped his attention, and surely he wasn’t alone in such sudden insight. Despite intense efforts he had never succeeded in bringing attention to or engineering the erasure of Old Towne’s alley debris. Therefore, cover said debris in graffiti, and the necessary attention would be drawn.

Haycraft had the ideas, Lambret the ability. Their projected canvasses rarely consisted of flat surfaces, and Hay could hardly draw a coherent line by hand, much less with a spray can. But in the way a poet tackles a devilish meter to express his thought and finds the restriction inspiring a more luminous work than would the endless freedom of blank verse, Haycraft discovered his vision in his absence of finesse. Never miss the majestic villa hidden in the tight villanelle, he quipped. He would undertake his project with a monochrome aesthetic: all surfaces laminated in gold.

He swore the boys to not indulge in any momentarily inspired, improvisational creations. The plan throbbed with such promise that he took the worrisome step of adjusting his daily schedule: First he consulted his calendar for the upcoming moon phase (the success of new projects required getting started before the new moon); he took the bus to a suburban hypermarket and filled a rolling suitcase with materials; then he arranged three twenty-two-minute meetings with the small band of aerosol guerrillas in his apartment. There he presented the boys with targets marked on a district map hung over the chipped plaster of his apartment wall and disastrously hand-drawn by Hay himself. Boys he had come to like, even admire, despite the sharp chemical stench. He surged into the awaiting room like water rushing from a burst main, overwhelming the boys in seconds. He sat with them on the couch with one large leg crossed in front like a railroad gate, curling his arm over the back to clutch a boy’s shoulder, careful never to touch anyone above the knee for fear of alienating him. He drank water from the same glass of any boy he spoke to, thinking such earthiness persuasive. Over three short evenings Haycraft exulted in his hidden capabilities as a general, delineating missions for each group of three clad entirely in black, provoking them with fiery (but brief) motivational speeches before launching the lads out with his blessings, into the dark.

—It’s true I ask you to take grave risks, Haycraft admitted. But remember the hand that builds is better than that which is built. Better and nimbler than the hand is the thought which wrought through it, as Emerson so rightly remarked.

The boys hardly understood him and did not care. They liked the idea of their work being somehow sanctioned, and here was an adult with a place of his own, a place where any or all of them were welcome to crash. They thought him nuts but cool, an easy touch.

Meanwhile Haycraft continued his scheduled forays to the Don Quixote, as a cover.

—In order to retain a sense of normalcy, he explained. To delay suspicion. This mission is illegal, I want you all aware of that. It must be dispatched in total secrecy. You are to be artful terrorists; harbingers of an awful beauty.

Haycraft was not interested in the threat of arrest. He believed civic disobedience should be anonymous, so that a government could never be certain how large a wave of unrest they were dealing with, thus leading them to suspect the worst. He believed in covert coercion.

The boys launched themselves out his door in giggling glee. Each night, Haycraft inspected their handiwork as he walked home from the Don Q, humming his light Foster tunes and smiling to himself at three in the morning, on schedule, the full moon still some days away. And he was happy to open his door upon the splayed form of Lambret each time, asleep on the covered couch beneath a dusty sheet, among another boy or two on the floor. He stepped lightly over the wagging tails of curled dogs, trying hard not to be frightened, and ignored the soiled rag in Lambret’s hand.

Four nights’ work and the task was done. Mission accomplished: Immediately the new artworks entered the conversation of the city; citizens began to take note of the lengths of pipe and rolls of wire mesh resplendent in gold beneath radiant sunlight. Snap judgments occurred on the merit of the works as art – usually asserting the negative – but the point was that the debris was now noticed. With outrage and an inward shudder, in most cases, and in these instances the Board of Aldermen passed motions to have the works removed. As had been planned and hoped for all along.

Added, unforeseen benefits were of consequence, too. A handful of the works were left to stand in the forsaken corners where the boys had mounted the debris in a kind of foundobject sculpture, met with a puzzled shrug by the average Old Towne individual, few of whom claimed to have much insight into the baffling absurdities of Contemporary Art. High-res photographs appeared in Montreux Magazine and in the new color editions of the newspaper. There were discussions on the local talk radio, and brief investigations on the nightly news. Such small successes were only an added award in Haycraft’s view. What mattered in the end was that the debris was gone, and his neighborhood’s grand architectures now had the chance to breathe.

Haycraft was aware this achievement was due in large part to the abilities of the boy.

At the Don Quixote, the regulars fells into ripe discussion. An operation on such a large neighborhood scale overthrew even baseball as a topic of debate; the world could have been covered in gold for the intensity with which they evaluated the act. Romeo stuck to his indifference – he kept his 1968 BMW out of the alleyways and the debris had never bothered him. Beau Stiles said he liked the spirit of the thing, though he wasn’t sure he understood it. A grumbling Chesley Sutherland declared it still vandalism, and that if he were allowed to return to duty he would get the bastard kin who were at the bottom of it, rounding up all implicated by martial means. He said this with an eye cast at Haycraft, who everyone suspected had been secretly involved. Haycraft turned his palms upward, baffled by the attention.

—Always a crime somewhere, always some punk looking for an arrest, Sutherland muttered. And here I am stuck with you guys, making sure you don’t hurt yourselves.

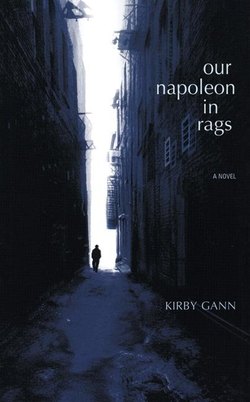

Just then Romeo Díaz raised his glass and launched into a mocking toast, christening Keebler Our Napoleon in Rags, a moniker Haycraft disparaged haughtily among the other regulars as insulting, but one that at home he quietly cherished, using the title to sign his notebooks.

—Although I’ve never appreciated the warlike spirit of any man, I have always admired the figure of Napoleon in history, Haycraft explained once, alone with Lambret. Emerson wrote a laudable essay about him, you know. He spoke of the man as a figure created by the people, by the times. Europe gave birth to Napoleon out of necessity, and he rose to the demand. I cannot imagine a more noble call to heed.

Quietly the Don Q regulars came to tolerate the new presence of the boy in their cloistered world. Lambret’s profession in the park was something of an open confidence – not that he hid anything by his low-slung black jeans, the loose, dirty T-shirts that hung on his lithe, nearly frail frame, and the pouting, helpless stare that seemed the default expression of his face. They tolerated him by not beating him to a pulp any time he followed Haycraft into the bar. But their uneasiness was palpable: No one could see what the boy could possibly want with a man like Hay that did not imply manipulation. As a ward of the state, Haycraft did have consistent money coming, and his family had provided a very small trust – Beau and Glenda concerned themselves with that possibility. Romeo disliked Lambret because of his sexual ambiguity; he detested such confusions on principle. He thought boys should be all boy, playful and destructive and ready to goof until the age came to get serious. (Whenever that was.) Chesley Sutherland thought the kid a punk who had lured Haycraft into pedophilia – a crime. He did not want to be forced to tip off his contacts on the force, but Chesley believed he had to do what he had to do.

What bothered them all, strangely, was apparent affection. Haycraft’s hand calmly stroked the black, almost French curls of Lambret’s hair; his palm rested easily on the thin neck as they gazed together at the television behind the bar. They leaned into one another in all occasions. They worked together closely – unusual work, too, with Lambret reading aloud from Thoreau and Emerson, and Haycraft interrupting to make a gentle corrective of pronunciation or else expand upon the writer’s ideas. This sight eased Beau and Glenda’s concerns a notch on their inner dials, but the regulars did not know what to make of it: They felt forced to watch the two incline their heads toward one another over a table, sharing a smile, a gentle touch, the pleased pucker of Haycraft’s lips. Eccentricities of character were ably assimilated here; there is a kind of friendship where people appear ready to bare their teeth on the other’s throat, and they continue like that all their lives yet never part. The Don Quixote was filled with such friendships; as Sutherland said, Everyone here’s fucked up some way or other.

Now there they were, confronted by one of their own in the company of a fifteen-year-old boy.

—And not all boy at that, Romeo insisted. And he may not even be fifteen, I’m not convinced.

Chesley snickered. He told Romeo he sounded jealous.

—Maybe you need to get out to that park and get your own Lambret, man.

The idea held such promise to the suspended cop that he could not resist further extrapolating on the possibilities of what a Lambret could do for a lonely Romeo. Although Romeo could not afford such luxuries, Chesley added. He nudged Romeo with his elbow.

—What the guy needs is a woman, I’m telling you, Romeo said, ignoring him. Someone who’ll take care of him, not the other way around. I mean look at the kid: He’s halfway to bitch already. I’m not convinced Hay’s into male ass.

The others didn’t respond. They continued to stare at the two in their booth, trying to act like they were not staring. Haycraft’s sexuality had never been touched on in conversation before: It was not a subject worth pursuing; the guy was as sexual as a plant. So they thought.

They continued to watch and wonder as Lambret read aloud from a thick volume while Haycraft lounged, his head reclined on a pillow situated as a headrest behind the booth, his eyes closed in contentment.

—Maybe he plans to adopt him, Romeo ventured.

—I don’t think that’s the kind of daddy the kid is looking for, answered Chesley.

The two laughed a long time on that one. They were able to milk that one for weeks after, every night, any time the hours turned slow.

Beau thought such speculations hurt morale.

—You two hush up about that stuff, he said. I’m trying to sight the positive. That kid has a hard road and look at how Hay’s getting him turned around.

—If I find Hay’s getting it from the chicken here I’ll take him down, I don’t have a choice, Chesley spat.

—And I got a security camera showing you with a gun when you’re not even on the force, Beau said.

—Not officially! Officially, I am not on the force. For now.

It was enough to shut Sutherland up. He needed Beau to vouch for his character at his deposition for reinstatement. Beau would do so, regardless of what Chesley did in the Don Q as long as it did not bring the place down – having a contact on the force can only help a nightclub owner in the long run.

If anyone would have thought to ask him, Lambret, after a good fumble for words, might have explained his relationship to Haycraft as similar to student and tutor. A charged relationship, yes, but when he thought over the details of their brief time together – Lambret was living in Haycraft’s apartment within a few weeks of meeting him – he saw the older man teaching, himself doing his best with addled mind to listen. He was a boy in a hurry to grow out of childhood, and Haycraft opened the gate to a region reserved only for adults. It did not matter that these adults did not like or trust him; Haycraft assured him that eventually they would. And despite his velocity toward adulthood, Lambret still needed the example of an older man, however bent and tattered the model may be.

Haycraft gave the following explanation to Beau:

—He doesn’t want my money, he never asks for anything. We read, and discuss, and I believe he is making great strides, then he disappears for days. He comes back, and I only need remind him of his father’s example to set him straight for a while longer. His father was an adjunct professor, you know. Lambret mythologizes him, the bewitched genius too close to the flame sort of thing. That nonsense. But I’m slowly bringing him around to admit that the father is only an addict, that whatever gifts he may have had he let go for junk.

Haycraft had come to understand the powerful grip of the rags the boy carried, and his supply of aerosol cans, modeling glues; he had no use for the willful dulling of a mind. If Lambret preferred highs to the difficulties of concentration, Haycraft insisted he do it elsewhere. And often, the boy did. But always he came back, stray dogs panting in tow.

—Speaking of fathers, Hay, doesn’t it bother you where he does his business? That’s Edmund Keebler’s statue they pass around. I would think that would bother you.

—My father is not watching, Beau. That statue is not my father.

What Haycraft would have liked to have said is: What business is it of yours? What if, when the boy arrived in early morning, considerate of the time so as not to disturb Hay’s schedule, what if Haycraft opened his door to find Lambret standing alone, his face downcast, his fatigued eyes confessing to how absolutely lost he felt? What if Hay allowed the boy inside, and as he scolded him over his lack of hygiene, began to run the bath? If Haycraft then watched the boy undress and crouch into the tub, then kneeled there beside him, sponge and soap in hand; if he set to agitated humming while he lathered the boy’s soft skin and saw the white flesh redden with the hot water; if he then dried the boy himself in the thickest towel he could find before leading him to the bed to rest. And if Haycraft decided to rest then, too – what of it? If Lambret stretched his thin body long across the coverlet and let his towel fall aside, lying quietly while Haycraft traced shaking fingers the length of his legs, his back, the line of his jaw – was it anyone else’s concern? The boy had been providing himself long enough to have forgotten safety; he was as stubborn and clever as Copperfield without any of that character’s charming innocence. Haycraft saw his ministrations toward the boy as acts of cleansing – washing away the street, the chemicals; washing away the ignorance from the urchin’s mind. Haycraft wanted to gather the Don Q crowd before him and shout: I am not Mather Williams’ cousin dragging the boy behind a dumpster, steak knife in hand. He was convinced that Lambret, his discovery, had no one but him, and Haycraft’s very being was composed of an irascible need to save someone.

It was Glenda who finally mustered enough courage for a direct interrogation. Haycraft gave away nothing:

—We teach each other, he said. It’s very much in the spirit of the Ancient Greeks: I give of my learning, and in turn he gives of his goodness and his will to learn. An eye-opening proposition for me, as I’m sure it would be for you also, Glenda. Like being allowed a glimpse of the future. Lambret has both man and woman in him; he embraces both, both archetypes. That is the way of the future, and I want to understand it.

Glenda smiled. She could display an accommodating smile, one that pinched the corners of her mouth and stretched the thin mauve strips of her unpainted lips, but which had no effect on her eyes. Her eyes remained steady, the flesh about them loose and puckered, thick, soft. It was a smile that said take your time when waiting for a patron’s order, exhibiting infinite patience even at those moments when she had none.

—Yes, very much like the Greeks, or the Romans, Haycraft continued, rolling now. Don’t you see how this folds into all my other endeavors? We read together as in Augustine’s time, when reading was communal and our modern notion of tackling a book in solitude would be passing strange to society, when to read meant to listen; to own a book was to memorize it for recitation – note this down, Lamb, here’s a future editorial subject; perhaps we have become so cut off from one another in this age because of our approach to reading, the massive distribution of books for sale rather than a borrowing-in-common; certainly the isolation of television-watching has its impact in this too; yes, this is a thought worthy of pursuit, it fingers everything....

—Yes that’s all very nice Hay, but remember Beau and I aren’t running a public library here and your friend is very young in the eyes of the outside world, chided Glenda. I’m asking you to keep in mind our situation.

—Yes, yes, of course, I understand. But you must understand that there is something so appealingly vague about him, like holding a memory, a comforting and nostalgic memory.

—The memory I have is coming to see you in the hospital, Glenda answered, covering Haycraft’s hand with her own. She was referring to a time in Hay’s twenties, when he had first become infatuated with another boy from the streets who ended up beating him when Haycraft refused to be more forthcoming with his money.

But Haycraft and Lambret were no longer following her. They were looking past Glenda, toward the half-wall that separated the dining room from the bar.