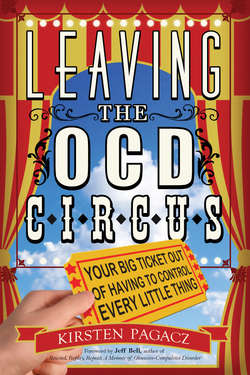

Читать книгу Leaving the OCD Circus - Kirsten Pagacz - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Cleaner Is Better for Sergeant and Me (OCD Is Morphing)

ОглавлениеAs a child, I believed that a pure, good, and perfect life looked something like the household cleaning commercials that I saw on TV. Some lucky kid's mom is so happy and looks so nice. She steps into her sunny kitchen after using Mr. Clean on her floors and counters. She's smiling and relieved. Her kitchen is spotless, bright, and clean. All I could think was that she was so lucky to have met her goal and her kids were equally fortunate. That TV world looked so ideal; it appealed to me on a deep level.

My bedroom was my world, and I had goals, too. I kept it to the maximum clean, just like in a TV commercial: tidy, straightened, dusted, and polished. I controlled this environment. Anything less was just not right. I no longer accepted uncleanliness and disorganization, and, more importantly, neither did the Sergeant, who was no longer soft-spoken at all.

I had a “socks-only” drawer. All of my socks had to be folded exactly the same way, into tight little perfectly round balls. They had to face the same way and line up perfectly, side by side, in color-specific rows. If a sock was not rolled right, I would unroll it and roll it back up again until it was. This felt critical to my well-being.

Under Sergeant's command, I controlled a sterile and perfect environment. I controlled all the objects and all the space between the objects. The lamp had its perfect position on the table. I made the bed the exact same way every day. The sheets were tucked in tight, and the top sheet was folded and creased perfectly to a straight edge. Nothing out of place, ever! Nothing dusty, ever! I lived by a doctrine of complete and utter order, Sergeant Style. Commanding the order of things on the outside made me feel better on the inside. The reward was intrinsic.

My mother didn't seem to notice that anything was wrong. She was thrilled that I was so neat. I was like a waitress in a diner, constantly taking care of her station. Wiping down tables and straightening the salt, pepper, sugar, and creamer; I had to control all the elements. Things started to have to be a certain way or I would feel off inside and uncomfortable.

Keeping up was exhausting, but the rewards made it all worthwhile.

One day, while recleaning my room, it suddenly occurred to me that inside and at the top of my bedroom closet there was a bright and bare lightbulb that I'd never dusted. Sergeant was right there to show me who was boss: “Because that bulb has never been dusted, your room has never been absolutely perfect and clean,” he said as if through clenched teeth.

I sank into disappointment. That was all I needed to hear. My room was no longer perfect. It was tainted, contaminated. Clearly, this disturbing situation would have to be rectified immediately. Thoughts of this impure, dusty bulb way up high in my closet filled my mind. I was edgy and distraught. Nothing was going to stand between me and that dusty lightbulb. Nothing!

This was the '70s and pretend kitchen sets were the rave for little girls. I was lucky to have one. My mini kitchen table set was badass; it had four little chairs with shiny vinyl leopard-print seats—the coolest. When I was in the mood for entertaining, I would often set one of my Siamese cats on one of the chairs and turn on my 45 rpm record player. My cats never stayed too long; they never made it through a whole song. But I was glad, if only for a little bit.

Back to the scene of the crime, I dragged one of the leopard-print chairs over to my closet. My plan was to stand up tall on the chair and dust the bulb and its white metal base. With Windex in one hand and a clean, soft cloth in the other, I ventured upward toward the unclean bulb, but no matter how much I stretched, I could not reach it.

Next, I gathered some large books from my bookshelf. Of course, all the books were lined up in order from smallest on the left to largest on the right. I stacked some of the books on my chair and climbed up. But even after standing on the books, I was still not tall enough to reach the impure bulb.

I could not disappoint Sergeant. It was important that I was obedient. He did not like to be kept waiting.

That's when I spied my gerbil tank. It looked to be just about the extra height I needed to reach the bulb.

I loved my two little gerbils. They were my cute little friends, and I loved to watch them play in the wood shreds and curls. To shield them from my cats and thus a potentially terrible fate, I'd always kept a piece of heavy glass on top of their tank, leaving a small opening so fresh air could get in but our three Siamese cats could not.

With all my strength, I got my arms around the tank and carried it over to the chair. All right, everything was coming together now. I had the chair, the books, and the glass container. Really, this plan seemed like a stroke of brilliance.

I took the stack of books off the chair and put the gerbil aquarium on it. I then slid the heavy piece of glass over to completely cover the top. I knew I'd be quick and efficient and my little guys would have more air soon. Then came the books in their perfect stack.

I had no trouble climbing up my well-thought-out stack of items. Windex and a soft cotton cloth in hand, I made it to the top, standing with my feet aquarium-width apart so as not to break the glass.

My Windex was opened, and I had it on spray. As soon as I aimed at the bulb and sent out the first squirt, I started to feel relief. Wipe, wipe, wipe the dusty bulb with the cloth. The situation was looking promising.

But Sergeant wasn't satisfied. He barked, “This job is not good enough. You need to take the bulb out of its metal base and spray into the hole where the bulb goes in. The whole area needs to be clean, not just the meager little bulb!” Craving some peace of mind, I knew I'd have to do as he said; there was no other choice. This time Sergeant really went for it. “If you ever wish to be loved again by your family, you have to complete this task.”

So, with the cloth covering my hand, I unscrewed the hot bulb and took it out of the hole. I could feel its heat through the cloth. I aimed the Windex directly into the hole and squirt, squirt, squirted the spray right in. Then, with cloth-wrapped fingers, I reached into the hole and began to wipe.

The electrical charge hurled me to the floor. From the tips of my fingers, the electricity surged through my body and straight into my toes. I landed on my back—the books, aquarium, and chair thrown in all directions.

Lying there on the floor, unable to move, I was certain that I had been electrocuted and died, like the boy I'd heard about who lost his life on the train tracks. So I kept my eyes closed for a little while. I thought that I should wait for my angels to come get me and take me to heaven.

When the angels hadn't come after a few minutes, I thought that maybe I'd gone straight to heaven. I cautiously opened my eyes. Wow, I thought, How funny! Heaven looks just like my bedroom; maybe they are welcoming me with something familiar. The dizzying effects from the fall started to wear off, and eventually I sat up and looked straight ahead into my closet. One end of the glass top had come down hard during the fall and was now inside the tank.

I got up and slowly walked over to take a closer look. The situation was awful: the glass, like a guillotine, had chopped into the exact same spot on the back of the gerbils' necks, and their eyes had popped out and were still attached to purple tendons. It looked like a scene from a horror movie. I couldn't believe what I saw, and I felt so guilty.

I could feel the complete silence of my bedroom, and a deep, overwhelming grief—not only because this had happened but because I had done it. I had killed my little friends.

Oddly enough, Sergeant wasn't angry. In fact, he was reassuring. “Don't worry too much; you did the right thing. After all, the bulb had to be cleaned.” Sergeant spoke with an incredible confidence, and I believed him.

As awful as I felt about my little guys meeting a terrible death at my hands, I also felt so good that the hole under the lightbulb was now clean and dust-free, that the lightbulb was spotless, and that the Sergeant was pleased with me. The reward of pleasing Sergeant was just about the best thing ever. And for the next twenty-three years, I did whatever he asked, no matter how strange it got.

Although I don't remember exactly, after my electrocution, I most likely headed outside to look for someone to play with in the neighborhood.

I was lucky; my neighborhood was loaded with kids, and a lot of them were close in age. If I was particularly lucky that day, my best friend Victoria, who lived a few doors down in the same townhouse, could come out and play. Maybe we would have cartwheel competitions on our neighbor's front lawn, or we'd get Oana, a girl whose family came from Romania, to come out and play, too; this way, we'd have more judges and contestants for our cartwheel competitions. Or to scrounge together some change, we could return my mom's Tab soda bottles at the neighborhood grocery store that was a couple of blocks away. Then we'd buy red licorice for ourselves and start eating it in the alley on the walk back home.

Usually, there was a game of Kick the Can starting up somewhere, or we'd jump on our bikes and go exploring. We were really living all right, and we came home with dirty, grass-stained pants and sometimes a hole in the knee from a rough landing while doing bicycle ballet.

Today I am grateful for growing up in this neighborhood and all my memories of the great adventures that took place between the mulberry trees and the old oaks. Growing up there, on the south side of Oak Park, gave me a really solid base, a core of joy.

Even though Sergeant was bobbing in and out—that was how my OCD worked at this time—there were even stretches when Sergeant seemed to take most of the day off.

Photo: Victoria Moran/Illustration by the author