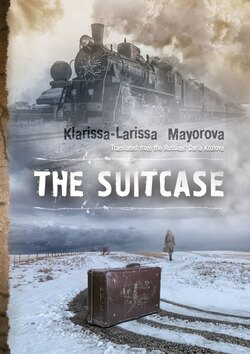

Читать книгу The Suitcase - Klarissa-Larissa Mayorova - Страница 2

Chapter 1

1942

ОглавлениеVera ran with the dog to a dug-out shelter. A dozen steps were left. A huge suitcase just slightly higher than her own weight made it impossible to move faster, but the woman grasped the handle tightly. Her strength was lacking. At last, she dragged it to the trench and dumped it in. Then she gripped on the dog’s fur and tumbled down after. The woman raised her head – a German plane circled over the village. It was like a howling death sweeping through the sky that was about to crash upon her. Blast! The second one. The third. Vera had covered her ears with the hands and, with all her might, pressed herself into the ground. She wished she could squeeze into its tiny gaps, and the earth itself shuddered and wailed helplessly. It seemed like this hell would never have an end.

She heard a piercing cry splitting the air. It was a child’s cry. Vera stood up on the wooden debris lying around and stuck her head out of the shelter. A five-year-old girl was standing on the porch of a house.

‘Sit!’ Vera cried to her dog and climbed out of the pit.

She was running as hard as she could. The plane made a circle and came back. Blast! The woman fell down.

Amnesia

Vera opened her eyes, and the bright sunlight dazzled her. She touched her head and felt the dried blood down her nape. She turned and looked around: pieces of rusty iron sheets, wooden boards, debris, broken glass were scattered everywhere…

From around the corner of the half-ruined house ran the dog. The clods of dirt swayed on its white fur, and ribs protruded out of its exhausted body. It sat beside the woman and started licking her hands.

‘Go away!’ Vera removed her hands away in fright and struggled to her feet.

Wagging its tail, the dog trotted around the woman, sat in front of her and started licking her face with a long rough tongue from chin to forehead.

‘Phooey,’ Vera spat, ‘phooey.’ The tongue got nearly into her mouth. ‘Seems like you know me,’ she thought.

She frowned and tried to remember how she had got here. It had been to no avail. Vera leaned upon the earth, blanketed with ashes, and tried to stand up. The wave of nausea began to cramp her throat. She got up. Then gradually, the blackness blurred before her eyes, and like the theatre curtains, dispersed, opening a new scenery.

‘Oh, God,’ Vera’s whisper was constrained by terror. She slowly turned around.

Debris of destroyed wooden houses surrounded her and only the chimneys of bare Russian stoves rose above the ruins here and there. The thick layer of dark-grey ashes covered it all. The wagon lay upside down. Flies were buzzing over the dead bodies with the sickening sound. The heart moaned, the breathing got faster, and suddenly she found herself shaking and her teeth chattering.

‘Where am I?’ Vera kept asking herself, looking all around. Her thoughts tossed in a frenzy, she clutched at her head and suddenly heard people’s voices and crying. She took off running towards the source of the noise. The dog raced off after.

The group of people, mostly women, were hauling corpses and gathering them in the pit. On the side of the road, lay the wounded with the two old ladies fussing around them. Vera ran over there and started examining the wounds.

‘I need the medical instruments!’ she cried out unhesitatingly.

‘My child,’ the old lady shook her head, ‘What instruments? In the whole village we could barely find a shovel.’

‘Needles, thread, knife, scissors, bandages, rags, water, matches!’ ‘Bring all that you have!’ not listening, insisted the woman.

* * *

After she had a thread and a needle, Vera stitched the wound of a teenage girl. Led by muscle memory, her hands were working faster than she was thinking, as her thoughts merely tried to catch up with them. She had no idea why and how did she get these skills but every action performed by her hand was confident and professional. Vera deftly operated with a limited number of the simplest tools, giving the injured medical help.

‘That’s it, I did the best I could. They need a hospital now,’ the woman said, seating herself on the ground. She rested her hands in her lap and was gazing down, thinking.

Then all of a sudden, she smelled the tobacco smoke. Vera raised her head and saw an old man standing smoking. ‘Curious to know if I do,’ wondered the woman. She reached her hand into the trousers pocket and groped something that shaped like the pack of cigarettes. She lighted one. The women who were conversing together in low tones stopped talking and looked with judgment at the smoking woman with an unnatural colour of blonde.

‘Child, you saved us again. Yesterday you saved my little grandkids from starvation having fed them. Today God has sent you again to help the wounded people.’ ‘God bless you,’ she crossed herself and motherly added, ‘You’re a good soul, but you shouldn’t smoke. By the way, where’s your suitcase?’

It felt like a punch to the face.

‘Suitcase!’ cried Vera, and jumped to her feet, without even realizing that she got her memory back. ‘Rudy, follow me!’ she commanded to her dog and ran back to the place where she had awoken.

* * *

‘Come on, where are you?!’ throwing aside the destroyed house’s rubble, Vera kept asking anxiously.

Abruptly she stopped stiffened at a loss. Though she retrieved her memory back, some of its details erased. ‘Where had I left my suitcase? I’ve never even let it out of my hands,’ Vera was desperate to remember.

Near the wagon bustled a hungry dog nosing and sniffing the corpses.

‘Phooey,’ screamed Vera shooing the dog away, ‘Come to me!’

Wagging its tail cheerfully, Rudy came up to the woman. She patted the dog and commanded, ‘Seek!’ The hound brought her to the dug-out.

‘Thank God, it’s here!’ Vera felt relief. She descended into the pit and attempted to push the suitcase out. Her feet rammed down, and her arms and body pressing it to the earthen wall Vera tried to move the weight up with her knee.

‘Please, come on!’ her strength was ebbing fast, and the suitcase only slowly slid down. ‘Let’s put the wood boards under the feet,’ decided Vera. She poked her head out of the shelter, and an image of the girl on the porch flashed in her mind. A suffocating knot jammed right in her throat, and the gush of tears was breaking through. Vera dropped down on her knees and began to cry bitterly.

* * *

Vera slowly walked down the unpaved road, hauling the heavy suitcase that strained her arm. The dog trotted somewhere ahead. At once, they got overtaken by a wagon with the injured people.

‘Whoah,’ drawled the reins an old man, ‘I’d drive you, but my cart is full.’

The woman noticed the guilty tone the old man’s voice and replied soothingly —

‘It’s okay. Never mind. Go. I’ll reach the station slowly. Am I on the right road to the railroad station?’

The old man sighed. He pointed with his hand in the direction of black with the smoke western part of the horizon.

‘Go straight and turn left on a crossroad. Germans bombed it yesterday. Barely there’s much left of it. Chugunka’s damaged. They say the hospital train stopped there. Here may it will pick our wounded also?’ the old man whipped the horse with reins. The wagon creaked into motion.

‘Wait!’ ‘Wait!’ cried Vera, ‘Sir, I beg you, drive my suitcase! I’ll run after the cart! I really need to get on that train. I have to.

The old man looked at the frail woman with a heavy suitcase in her hand. His kind heart couldn’t resist, and he agreed. He got down, heaved the trunk on the place where he had been sitting, and walked beside the cart, holding the reins.

A fierce sun climbed at the zenith. It burnt like hell. The cart arrived at the station, where a green train with red crosses stood motionless right before the mass of mangled metal – rails damaged by yesterday’s bombardment. Women, children-teenagers, oldsters, soldiery, and men in civilian clothes scurried around repairing the railways.

Military medical train

‘You have to understand!’ a tall sixty-five-year-old army doctor in a uniform shouted at Vera, ‘It is a hospital train! We do not take passengers! We head into the thick of the fight and pick up the wounded! Furthermore, Kirov is back that way! And that is the way you are to go!’

He turned and quickly walked away.

‘I know,’ Vera tried to catch up him dragging the heavy suitcase which was skidding from side to side, ‘But your trains don’t usually come here. Only a local ambulance train goes through the station. Their final destination point is about forty kilometers from here, and then you go back to Kirov.’

The man quickened his pace. Having failed to keep up with him, Vera shouted in despair,

‘I am a doctor! A surgeon!’ I’ll assist you with the surgeries!’

The doctor’s foot hovered in the air for a second and slowly put down. All of a sudden, the man turned and looked at her skeptical. Only then he noticed that the woman wore men’s trousers and a plaid shirt looking like the one of a man too.

‘Okay. There are the wounded from the village. Let’s see what you’re made off. The ninth car – surgery, wait for me in there. I’ll come in no time.’

The doctor left quickly, and Vera hurried to the ninth car. She hauled the suitcase into and ran to the train driver.

A thin low man in oil-stained overalls was doing the check. He was moving along the cars while Vera, mincing after him, tearfully begged him to allow the dog on the train.

‘People starve, and she wants to keep a dog!’ shouted the man, then bent down, and climbed under the car with a massive wrench in his hand.

Vera grabbed his foot and pulled with all her strength back.

‘You, piece of trash!’ he fought back with the other foot and shouted, ‘Get out of here!’

‘We can’t leave this dog! It is exceptional! I’ll feed it my rations!’ Vera’s voice was breaking into shrill from tears.

‘Let it be,’ the machinist frowned, ‘I suppose it’s really something special if you’re ready to starve for it. Drag your goddamn dog here.’

* * *

Darkened. Vera and the doctor finished the operation. She’d been up for eighteen hours, and eight of them she had been standing rooted to one place. Pain in her legs felt like one tried to tug veins out of them. She bent one leg and rubbed the other under the knee. ‘It’s alright. I’ve had worse,’ kept encouraging herself the woman.

Vera proceeded to stitch up the incision. The doctor watched her closely and observed mentally, ‘Perfect. That’s pretty good, lady. How old must she be?’

The woman cut the thread with scissors and carefully put the tool on a metal tray. It clinked softly onto the iron. The doctor considered that curious and glanced at Vera – his stern look vanished. His eyes were weary.

‘Thank you, comrade,’ said the doctor.

‘I’ve never worked with the gunshot wounds before,’ replied Vera, a bit defensively.

‘It’s okay. No one has. I was taught by Burdenko. And I’m going to teach you. The way you bandage wounds looks quite peculiar. It takes so much time and lots of bandages. Where did you graduate from?

Vera got taken aback. She couldn’t tell the truth, and the last thing she wanted to do is telling a lie. A confused woman waved her hand and, what was quite out of place, asked him to teach her how to roll a coffin nail. They left the wagon. Vera seated herself on the metal step. The doctor had pulled a scrap of newspaper and wrapped it around his finger, explaining how to roll joints. He filled one with tobacco and handed it to the woman.

‘We haven’t even introduced ourselves properly. I’m Konstantin Gavrilovich.’

‘My name’s Vera,’ with the fatigue in her voice, answered the woman lighting up a cigarette.

Injury

The train crossed the front line. At full speed, it raced through the rumble of exploding shells. Vera stood alone by the window thinking. She gazed at the black smoke spreading along the horizon. It was not death that filled her with torturing horror, but the risk of failing to bring her suitcase where it was needed the most.

She felt the train slowing down as it was arriving at the station. It started breaking, and came the noise of a decelerating train and the creek of its wheels grinding the rail. A steam engine stopped with a prolonged ‘f-f-f-f-f’ as if it exhaled its last breath.

The medical personnel got off the cars. The awaiting, among which stood children, women, old people and soldier men, dashed to the arrived. Konstantin Gavrilovich cried at the top of his voice.

‘Comrades! Split into groups of four or five. As soon as the wounded are sorted, you begin carrying them into the train. Soldiers with a red mark on the forehead or hand are to be loaded into the seventh and eighth cars.’

‘Vera, you take the station’s right-wing,’ the man instructed and hurried to the first group.

The railhead was packed with people. Moreover, it severely lacked medical stuff. Vera rushed from one man to the other. There was a Red Army soldier – not alive, but yet not dead: his eyes motionless, the pulse barely palpable. Vera yelled,

‘Eighth car!’

In a hurry, she explained how to place the wounded on a stretcher. Cramped by nervous tension, her hands shook, the beads of sweat ran off her forehead, and the shirt, wet with cold sweat, chilled her back. She had never worked with such an amount of injured people before. The white coats desperately lacked stretchers. The people, suffering from pain, were laid on the blankets, torn bedsheets, and dirty doormats. The cars soon got crammed. The number of men in each one was 50—70 more than it was supposed to take and far much more than any regulations and the number of seats could allow. Lying densely to each other, the wounded hid the car’s floor.

The load was finished. A crowd of worn off faces, silhouettes in bloodstained clothes stepped back from the railways. Vera waited for Konstantin Gavrilovich. She ran along the train, checking if it was ready to depart. But then a whistle came. It meant the air raid.

Germans had waited until they finished loading the wounded onto the train and now were starting the raid. A low-flying plane had shown circling over the station, it was easy to make out black crosses on its wings. The panic-stricken crowd bolted. Chaos. Vera looked up to the sky. A slanted chain of black grains – the shells – had been breaking off the plane. Tearing the air through with a paralyzing noise, they dived down. The earth shuddered. The whole world turned into a wailing and hissing thunder of black smoke. The woman stiffened petrified.

‘Vera, run!’ the scream of Konstantin Gavrilovich came from the smog.

She turned her head sharply toward the sound of his voice and saw the doctor falling. Vera rushed to him. Gripped by panic, fleeing in all directions, people knocked her down. Their eyes were mad with terror. The woman got on her feet and ran, keeping close to the train. The smoke burnt her airway and nose and was getting into her eyes. The pitch-black picture resounded with a deafening roar of screams, cries, and a burst of machine-gun fire shooting at the fleeing people.

Vera hurried to the doctor. The man was holding his stomach.

‘Things are bad for me,’ the words cost him an effort. A shard had torn his abdomen, ‘Flee, Vera. You must survive and operate soldiers.’

The woman made no reply but drew volokushi1from her backpack, laid the wounded man on it, and dragged him along the ground. Her corpus bent forward low, her legs weakened from the weight of her burden. Suddenly the teenage boy ran up to her. He gripped the hem of the tarp and helped to drag him to the platform’s wall to get somewhere safe. Vera’s glance flicked at the sky. Under the tiny patch of the clear sky, she saw a Red Star on the speeding Soviet warplane. Engines roared, and the sounds of firing came. Our pilot shot the enemy plane down. Falling down, the heavy combat machine ripped the air apart. As it approached the earth, the prolonged cry of the doomed aircraft had amplified deafeningly, but the last seconds before it turned into a mass of mangled steel, the sound ceased. In a fraction of a thousandth of a second, it said goodbye to its life. Then it hit the ground. Blast! The rumble reverberated for thousands of versts.

‘M-m-ma’am, ma’am!’ ‘Please, take me with you, to the front,’ stuttered a little boy tugging Vera at her sleeve. He had a burr in his voice. ‘I’m gonna shoot the German. I’m now all alone.’

Vera shuddered. Though the rumble of the explosion hadn’t died yet, she turned her head and stared blankly at the boy. Suddenly the woman clutched him in her arms and held him close. Then a tone of her voice turned unexpectedly serious – the one with which she would have talked to an adult.

‘Your front is here. Here you’re needed most of all. Who else will load the wounded onto trains? You understand? You’re so brave. Making responsible decisions is the most important quality of a doctor. And you’re already such a strong-minded boy. Yes, you’ll make an excellent doctor. But you should study well, okay?’

The boy nodded his head. The woman had lifted the crucifix off her neck and put it in the lad’s dirty hand.

‘It’s golden.’ ‘I hope you will get some bread in return for this. Now please help me drag the doctor.’

The boy put the golden crucifix on his neck and grasped the volokushi.

The Big Fire

The railroad was destroyed. The two last cars blazed with fire with people perishing inside. The world in turmoil. Gripped by the panic, women, children, old men were running, tripping on each other and shrieking. Out of the burning doors, shot the sheets of flame. And out of this diabolical fire, they were dragging out the people. Everyone was fighting the fire. A machinist crawled under the train to uncouple the cars.

‘Palych, where on earth you’re going?’ shouted a stoker Grishka, ‘Here! Here! Water!’

Grishka grabbed a bucket of water from the hands of a past running woman. With the full swing, he splashed it on the rail track. ‘Whoosh…’ billowed the thick black smoke.

‘Water!’ yelled Grishka.

‘Water! Water!’ shrilled the voices on all sides.

A nurse dashed back and forth, bringing the buckets. The water sloshed, splattering over the edges. Grishka rushed to her, seized the buckets, raised one high over his head, and poured over himself. In a moment, he was wet from top to toe. The second one he carried with him as he followed the machinist under the train.

An acrid smoke burnt his throat right away. He started to choke.

The machinist clothes were on fire, but he persisted in his work. Grishka smothered the blaze on his back.

‘Can’t turn the knuckle!’ shouted Palych.

Grishka hastened to help him. The clouds of pitch-black smoke shrouded the men, seizing them with a suffocating cough. The flame spouted from all sides and was scorching their arms, legs, shoulders, and backs.

Finally, they got cars uncoupled.

The stoker hauled out the burnt body of his friend, shouldered him, and ran towards the ninth car to the surgery.

‘Call a doctor! Doctor!’ cried Grishka, his face black from soot, hair disheveled.

In the opposite direction marched the people, unperceiving and shocked. Amid their trudging feet, throughout the platform, there were the body parts strewn. Flocks of crows, smelling food, circled over the scene of a tragedy.

Operation

The medical orderlies met Vera and the boy. They put the doctor on the stretchers and took him into the car. The surgery smelled of vapor as of the overcooked milk.

‘Prepare him for surgery!’ commanded Vera and retired to the sink. She scrubbed her hands. A nurse held her white coat ready. An orderly gathered Vera’s hair up to tie a white medical scarf2 on her head, but she dodged. She asked for a medical cap.

‘But it’s male,’ said the nurse with a look of surprise on her face.

‘Trousers I wear are male also. Now, what are you waiting for? Hurry up,’ Vera replied. In front of the medical team, a short, fragile woman grew into a confident and strict doctor.

Having no anesthesiologist skills, the nurse put a primitive Esmarch mask on the patient’s face, and the ether began dropping through the cotton wick. Vera proceeded to the operating table, took an instrument, and froze stiffened. A familiar dog barking struck woman’s ears. ‘Rudy!’ the thought flashed in her mind. She stood hesitating. The barking got louder. Obviously, the dog was looking for her. Vera pressed her foot against the heel of the other and pulled off a boot. Vera addressed the orderly.

‘Akim, there’s a white dog outside. Named Rudy. Bring it here to the vestibule and tie it up. Take my boot, he will follow you by my smell. Feed him my ration,’ Vera bent over the patient and set to work. The orderly grabbed the boot and, on the way out, bumped into Grishka with the machinist over his shoulder.

Deceit

Five days scared and exhausted people had been restoring the railways. And it was five days that medical staff had been on their feet. Five days Vera stood at an operating table. Between operations she went to the dog in the vestibule and fell asleep sitting beside it. It were precious 15—20 minutes of sweet rest.

It was getting dark. Vera stood at the car’s open door. After inhaling ether fumes for such a long time, she felt like swaying as if she was drunk.

‘We’re having a meal now. They should bring us food soon. Hang on,’ the woman said to her dog.

She took a deep breath of fresh air – and fainted. Akim came around the car whistling, with a plate in his hand. He looked at the woman lying on the steel floor and thought, ‘here she is, sleeping in the vestibule again.’ The orderly looked around and jumped into the car. He pulled the woman off the passageway and began to devour porridge. Rudy sat beside her still and watched the man’s every move without blinking. The dog licked his lips, and a long string of saliva extended to the floor. Rudy could stand the injustice no more and broke into barking.

‘Stay quiet, you, stupid mongrel. Off!’ harshly snarled the orderly and took a swing at the dog, ‘shut up!’

When finished the porridge, he quickly placed the empty plate beside the woman and walked away, cautiously glancing over his shoulder.

Vera regained consciousness. The dog greedily licked the plate, which clattered against the wall. The dog’s sunken sides shocked the woman. Thinned legs could barely keep Rudy up. They weakened. A stomach, cramped from starvation, made him arch his spine, having sucked his abdomen in. The poor dog whined.

‘So, have you eaten? That’s good,’ the woman stroked the dog. She got up and staggered to the next car to change her clothing. On her way, she ran right up nose to nose against the orderly.

‘Akim, have you fed the dog?’ asked Vera keeping her suspicious look on the man. The young man nodded without blinking.

* * *

It was late at night. Finally, complicated surgeries were finished. Shuffling their feet from fatigue, the medical staff was tidying up the operating room. From the vestibule came a woman’s shriek. Vera and her colleagues rushed to the sound of the voice. A young nurse, neither alive nor dead, stood pressed against the wall: her hands spread wide, and her fingers clenched in a death grip on the iron door handles. Not far from her there lay the dog with a swollen belly and remains of the human flesh in his teeth. In the middle of the vestibule lay a hand.

Vera shifted her horrified look on the orderly.

‘Where did you take the amputees?’ frowning Vera asked Akim.

‘As always, I carried them out in the bags,’ the orderly uttered defensively, innocently staring at her, ‘maybe the dog picked it up on the platform.

But it’s tied up here!’

Akim took a step forward and, bulging out his chest, rammed against Vera. He scowled angrily and yelled,

‘You’re depriving soldiers of food to feed a damn dog!’

‘I don’t eat a bite of my food but give it to the dog! And it was this damn dog that pulled 500 wounded soldiers from the battlefield!’ the woman screamed in anger. She took a step toward the orderly resolutely, ‘how will he work now that you’ve fed him?!’

‘Oh, screw you! It’s a mere dog!’ Akim pushed people out of the exit and jumped out of the car.

Lunch. The medical staff came to an iron dog’s bowl to share their chows with the dog. One spoonful, two, somebody dumped the half of one’s plate out. Having caught sidelong unkind glances of his colleagues, Akim reluctantly threw Rudy a piece of bread.

The railways had been restored. The train started and, gradually accelerating, left the station.

Heading into the rear

Vera walked through the cars, examining the wounded. She was slowly moving between the soldiers lying close to each other when she stopped near a very young boy. Suddenly the guy winked at her. Vera did not react but staggered out of the car into the vestibule. It was over! It was the last car. Exhausted, she leaned against the wall and crouched down. The woman closed her eyes and pressed her fist hard against the chest. She felt like to howl, but instead, she started to sing softly,

“The spring shall come, but not for me,

I shan’t see the Don spill its sparkly waters.

Where’s a girl’s heart in a raptured thrill

Shall race its beat, but not for me.”

Sounds burst from the woman’s heart, getting amplified by the sound of the wheels. She had not even noticed how loud her singing became. The words of the song caught the soldiers’ ears. Somebody’s hand slightly opened the door to the vestibule. Through Vera’s song, almost by the skin, they could feel the pain that had swelled in the soul of this small and fearless woman. When the song ended, there fell total silence. Not a single moan could be heard. Only the monotonous sound of the wheels filled the train: ‘choo-choo-choo-choo-choo-choo…’ The train carried the red army into the rear.

1

Translator’s note: Volokushi is a particular means for transporting goods, used by orderlies and nurses in the Great Patriotic War for the wounded Red Army soldiers’ transportation from the battlefield to the aid station or hospital. It resembled a sled and consisted of curved runners, covered with fabric and fastened with metal strips.

2

Translator’s note: Military nurses of the Soviet Union during World War II wore a triangular bandage, while a medical cap was considered a piece of the male medical form.