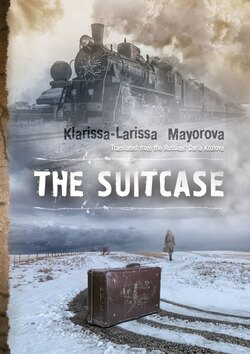

Читать книгу The Suitcase - Klarissa-Larissa Mayorova - Страница 3

Chapter II

Military-sanitary train

ОглавлениеOn the way

Vera was on the doctor’s round.

‘No, you’re not going anywhere. And now you’re not a doctor at all, but a stubborn patient who always wants to be restrained!’ Vera gently scolded Konstantin Gavrilovich, holding him in the bed while he was trying to get up.

‘Vera, I won’t walk. I will examine those who can walk into the bandaging room by themselves. Look at these girls – they’ve got bows on their hair. They barely finished school, slipped through the two-month nursing courses, they don’t even know how to bandage, and here I am, the doctor, lying in bed. Vera! Let me go,’ demanded the man removing Vera’s hands away.

‘Okay. We’ll see tomorrow,’ she covered the doctor with a blanket and hurried to the next car. Konstantin Gavrilovich pulled his head through the doorway and called out to the woman:

‘How’s our Palych? Who’s driving the train instead?’

Vera came back to the doctor. The woman struggled to hold back the tears but failed. She uttered in a choking, heart-breaking voice:

‘Poorly. He’s suffering. His burns are too extensive. He was burning but continued uncoupling the cars. I’ll operate him the day after tomorrow. I’m going to need your help, that is why I need you strong. And we’ve found a new machinist – a nimble old guy,’ the woman’s nerves finally gave up. Her teeth clenched her lower lip, and she hurried to get out of the car.

Konstantin Gavrilovich got up and slowly walked in the opposite direction. He moved towards the bandaging room.

* * *

The train had started to slow down, approached the station, and stopped.

The medical personnel left the cars. The bright hot sun hurt people’s eyes. Crowds of children rushed down the platform towards them. They swarmed around Vera, stretching their thin bony arms out to her and asking for bread. She looked at those little emaciated faces, into their beady eyes where the despair gave way to the hope of gaining at least the bread crumbs. The station’s military commandant strode towards the woman.

‘We’ve got 136 people injured,’ the man said, holding out his hand to Vera over the children’s heads.

‘We have nowhere to place them. We have people lying in the passageways. We can hardly breathe.’

‘I know. We’ve prepared several empty platforms with mattresses and are organizing coupling now. As soon as it’s done, we begin the loading.’

‘Okay!’

Vera turned around. Through the cars’ windows, the injured looked at the children.

‘Kids, let me through! I’ll get you some food,’ she said, but the children did not listen and trotted along with her to the car.

Vera jumped on the train and ran to a secluded place where she had hidden her suitcase. She threw off the rags and opened it.

The woman hesitated: she stretched her hands to the suitcase but paused for a few seconds.

‘Oh, Gosh,’ whispered the woman. Tears ran down her face. From a suitcase full of groceries, she drew cookies, hardtacks, candies, halva, and put everything in a bag. Tin soldiers fell out of an inner pocket. Vera had put them in back again, closed the suitcase, and covered it with rags.

* * *

Meanwhile, the wounded soldiers were passing a bowl from hand to hand. They put their rations in a common plate – a slice of bread, a piece of sugar, boiled potatoes. Having collected a full bowl of food, the soldier asked Akim to take it to the children. The orderly proceeded into the vestibule and closed the door. He picked lumps of sugar and bread slices and shoved them in his wide pockets hurriedly. Rudy sat near the car entrance. The dog observed the man.

‘Oh, you again. Get out!’ Akim shooed the dog.

The door creaked. Akim shuddered and looked with the startled eyes at Vera entering the vestibule. Rudy snarled, glancing askance at the orderly.

‘I have some food for kids, but your dog doesn’t let me pass,’ Akim said.

Vera pulled the dog away from the passageway and stepped out in the street with the orderly, where the children were waiting for them. The woman had picked an older boy from the crowd, gave him the pocket, and said sternly,

‘You’ll divide it all by yourself equally. Promise?’

The boy looked at the woman with large round eyes and answered:

‘I give my word.’

Akim gave the teenager a plate of food.

The children left, and Vera ran to load a new group of the wounded. Rudy followed her.

* * *

The eighth car was disbanded. Some of the injured were displaced on the flatcar. The empty wagon was provided for a group of newly arrived and people needing surgery. The train was ready to leave. People jumped off the car and gathered on the platform. Akim stood a few steps away from them. In front of him sat Rudy, baring his teeth and growling. His upper lip was twitching, the dog looked as if it was ready to attack the man. Vera watched them in silence.

‘Calm your nervous dog!’ Akim demanded the woman.

‘Rudy! Stop! Vera commanded the dog.

Nevertheless, the dog continued baring his teeth.

‘Get off, I said!’ the orderly swung his hand at Rudy.

Rudy started barking, and the fur raised on his withers. Akim backed down and waved his hand. The dog lunged at the orderly. With a cry, Vera rushed to seize the dog, but it was too late. A huge black mouth had bitten into the orderly’s trousers pocket. The frightened Akim, fighting off the dog, stumbled and fell down – Rudy had torn man’s pocket apart. Bread and lumps of sugar fell out of it. Vera had pulled the dog close to her, calmed it down, and leaned over the sugar.

‘Oh, you skunk! You’ve stolen it from children!’ she brandished her fist to throw a lump of sugar at Akim but restrained herself, realizing the product’s value, ‘I refuse to work with you.’

‘That’s not up to you! You’re not the train master! It’s still Konstantin Gavrilovich who’s making decisions here!’ the orderly yelled.

‘So go and complain about me!’ she replied sharply with disgust.

The woman marched away. The men on the platform, and those who still could raise themselves on their elbows, watched the scene in silence. Everything was quiet. Colleagues looked at the man with contempt, turned around, and followed Vera without saying a word.

Three soldiers stood near the car, smoking. The one with the bandaged shoulder took a deep drag, extinguished his cigarette, and threw the stub with two fingers. Akim was walking quickly along the train when the men blocked his way. Their sullen, threatening looks terrified the orderly, and he stepped back like a shivering hyena. The soldier swung at Akim and struck him with all his strength. The mighty fist of the soldier fell on the bridge of the medic’s nose. The hit man rolled down the slope. The soldier spat in his way and climbed into the car.

The Break Through

An elderly master’s assistant came running from the station. He took the stationmaster aside and, panting, said:

‘Bad news, Leonid Yegorych. The Germans occupied the next station,’ a man was trying to catch his breath, holding his hand at his heart. He took off his cap, wiped his sweaty bald head, and freckled face. ‘We just heard about it. People say we’ve beaten the Krauts off, but these must have been sent there for us, seven or eight of them. They’re informed that train is coming.’

The commandant frowned, and his face grew black as thunder. He told Vera and the locomotive crew the grave news.

‘We’ll fight our way through,’ the old machinist stated firmly, ‘pump water into the boiler at full capacity, and you, Grishka, stoke the fire hotter than hell, make the devils sweat.’

‘All right, uncle,’ the muscular guy answered briskly.

* * *

The train had started off and began gaining speed. In the ninth car, Vera and Konstantin Gavrilovich were preparing for the operation. The red army man was put on the operating table. The doctors were getting to work.

The train rushed along the rails, overtaking the wind. More and more often, the soldiers cast their glances at the scenery outside of the windows. A boy of about eighteen leaned against the window, flattening his nose against the glass.

‘Mushroom! Mushroom! We’ve passed su-u-uch a big boletus there!’ spreading his arms, the guy demonstrated.

The soldiers laughed.

‘And he di-i-id get a look at that,’ a man with an amputated leg drawled his words, ‘we’re rushing so fast you won’t see a big-boobed woman.’

The laugh echoed through the car.

* * *

In the locomotive, the fireman Grishka threw the coal with a shovel into the stoke. Hellishly heated air of the furnace burnt his body. He worked hard without stopping. The striped t-shirt on his body was wet as if it had been held in water. The drops of sweat sprayed all around. Salt sweat trickles rolled down from his forehead, getting into his eyes, blinding and stinging them, but he had no time to wipe his face. The train was approaching closer and closer to the occupied station. On the platform, the machinist noticed a group of Nazis.

‘Come On, Grishka! Come On!’ he yelled to the stoker, ‘We’ll get through! You’ve crossed the wrong guy! You don’t know uncle Vasya yet! Petka!’

The machinist’s assistant dumped the bucket of coal and ran to the master.

‘Open the blow-off valve!’ uncle Vasya yelled to the assistant with all his might.

Fascists took off running towards the train. A hellishly hot mixture of water vapor gushed out of the tap and drenched the German soldiers. They clapped their hands to their faces, and one by another, fell on the ground. In agony, they rolled on the platform, kicking their legs and yowling.

‘We’ve broken through! We did it!’ Grishka threw a shovel and dashed to hug the machinist. The old man’s brittle bones cracked.

‘You’re, uncle Vasya, Gorynych! Scorched Fritz with the vapor! Genius!’ the excited stoker couldn’t calm himself down from joy and continued squeezing the machinist in his arms.

‘Oh, come on! Ease up!’ Uncle Vasya quieted him.

The train scorched ahead, and the boy with his nose pressed against the window observed the fascists fall on the ground. He watched them and couldn’t understand why they were falling because there was no shooting seen or heard.

Since then, uncle Vasya was called Gorynych, and the train was called the Russian Dragon. After the war, Vasily’s wife would ask one day, ‘Why do they call you like that?’ ‘Well, there were times,’ the old man would answer.

Death

Vera carefully changed a medicated gauze dressing on the burned back of the machinist.

‘Hold on, dear. I’ll give you a needle, you’ll feel better.’

‘Vera, please, sit with me,’ Palych’s words were barely audible.

The man was lying on his stomach. Vera crouched down in front of him, and their eyes met.

‘No need,’ Palych whispered, ‘Don’t waste your medicine on me. I don’t have long. Don’t get mad at me.’

‘Hey, Palych, what d’you talking about?’ Vera lay her hand on the machinist’s arm and began stroking it. Involuntarily, her eyes became wet, ‘Why should I be angry with you?’

‘Well, it was wretched – our first meeting. And now you’re saving my life. You said the dog was kind of special. Tell me about it,’ the dying man asked.

Vera tried to smile, but her face only contorted into the grimace of pain. She looked into Palych’s haggard eyes and called the story to her mind:

‘Under Rzhev it was. There I got into a real meat grinder. I lay in the forest. Bullets whistled over my head, sideways, behind my back. I thought, so, that’s it: now the stray bullet, the bloody fool, will get me. Abruptly everything went quiet. Still, I didn’t get up. Some time had passed, and I heard someone breathing so fast, right into my ear. I looked up and saw a dog standing next to me, and the earth was covered with blood all around. There were more corpses on the ground than there were trees. I got up and wandered, the dog followed me. Abruptly, the dog stopped and walked in the opposite direction. I followed it. It led me to a severely wounded soldier. I raced to help him, but he only said, ‘Save the dog. I beg you. He’s special. He’d saved about five hundred men. Delivering a field first-aid kit to the wounded soldiers, that’s all that the dogs do. But this one by himself had dragged the injured men on sled-drags to the dugout during this winter. Totally white, he stays unseen on the snow. Bullets whistle, but he keeps crawling forward. Nothing can get him. His name’s Rudy.’ I gave him my word that I’ll keep this dog. And by that evening, the soldier had died.

There was so little life in Palych’s body that Vera could not hear him breathing – therefore, she did not notice and missed his last breath. Man’s tortured look stared fixedly somewhere in the distance. Vera observed his frozen gaze but continued muttering something inaudible, trying to understand at what second of her story his life ended. She touched his face with her hand and closed the man’s eyes. As a doctor, Vera must state the time of death, but still, instead, she continued babbling and squeezing his thin, lifeless hand with her trembling fingers.