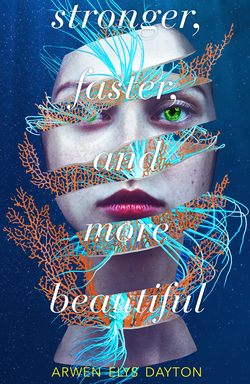

Читать книгу Stronger, Faster, and More Beautiful - - Страница 20

ОглавлениеElsie Tadd woke up in a room she did not at first recognize, with a dry throat, a throbbing head, and aches and pains all over. It appeared to be nighttime when she first opened her eyes, but when she sat up on the edge of the cot with the faded patchwork quilt, she noticed a hint of sunlight coming in through the window up by the ceiling.

“Church basement,” she whispered, identifying her location.

This was the spare room of her father’s old church, where he would sometimes sleep if he stayed late to speak with parishioners or to work on a sermon. Elsie knew the room well, though she hadn’t seen it in a long time. Besides the little bed, there was an old desk and a couple shelves full of dusty books—mostly rare versions of the Bible. One wall was covered by a rather beautiful mural that had been painted by Elsie’s own mother. The painting depicted God, in radiant robes, up near the ceiling, and below him was Jesus, healing the ten lepers who had called out to him on the way to Jerusalem. In the Bible, the men had said, “Jesus, Master, have pity on us!” but Elsie had always wondered how they’d been sure it was Jesus and whether they might have started out with something like “Excuse me, young fellow with the beard. Are you that Jesus everyone’s been talking about?” or maybe they’d called out “Jesus!” really quickly and waited to see if he looked around. When she was younger, Elsie had spent hours in this room, drawing and doing her homework, and she’d imagined painting speech bubbles over the lepers’ heads and filling in their words.

“But how am I here?” she whispered, because her presence in the church basement didn’t make much sense. Elsie’s father had been the minister of the Church of the New Pentecost for all of Elsie’s life, until a year and a half ago. Since he’d lost his ministry, no one in their family had set foot in the place. Yet here she was. “Did I dream about Africa?” she murmured.

No. Africa was there, in her mind, though it was like a mirage that lost its shape when you tried to look directly at it. Still, she recalled details—the city of Tshikapa in the Congo, the feel of thick cardboard in her fingers as she held up her protest sign; wet, miserable heat; everyone chanting.

The church was silent around Elsie, but she could hear the distant whoosh-whoosh of auto-drones commuting across the city. Her little brother, Teddy, used to run around this room saying “Whoosh, whoosh, whoosh!” while pretending that he could fly.

Teddy. The image of her curly-haired, seven-year-old brother brought other images along with it: Elsie’s mother sweating in her blouse and skirt, her green eyes alight with energy, leading the chant. Teddy holding a sign as big as himself that read I Am GRATEFUL For The Hole In My Heart!

Elsie swallowed, which reminded her of her sore throat and by association of every other part of her body that hurt. She felt her face. There were no bandages, only several spots that were painful to the touch, including all the skin around her right eye. The eye itself felt uncomfortable and strained, though she could see out of it perfectly well. She pulled up her long skirt to find bandages covering both of her knees, with scabs poking out beneath the edges of the gauze.

Another trickle of recollection came, as if through a haze of painkillers: A fall on a rocky patch of ground. A trampling of feet. Her father on a makeshift stage, singing and lifting his arms. Teddy, singing next to Elsie with all his heart: I was made this way! Oh, I was made this way! And the sensation in Elsie’s chest, the feeling that came over her whenever she thought about Teddy’s birth defect—the hole between the chambers of his heart that made him tired and one day might kill him—the sense that a giant had taken hold of her and was squeezing her ribs.

Maybe there had been painkillers, lots of them.

Elsie let her skirt drop.

“There really was a hospital,” she whispered to God in the mural on the wall. She imagined a speech bubble above His head that said, “No argument here.”

More images crept out of the shadows. There had been a clinic in a small building of decaying plaster on the edge of amuddy town square, a banner announcing Malaria Prevention and Treatment for Birth Defects. A line of Congolese women and children, waiting to be seen. Aid workers watching with irritation as Elsie’s father ushered his followers out of trucks to take places in front of the hospital.

More. A little Congolese girl, with beautiful dark brown skin and a sad face, standing stoically while a doctor gave her an injection beneath her belly button. Elsie knowing what the injection was: Castus Germline, the reason her father had dragged them to the Congo. Save the Third World, even if the First World has been lost. Once inside the body of a young girl, Castus Germline would edit diseases out of all her eggs and edit in protections against malaria and other infections, so that her children’s and grandchildren’s health would be close to perfect. Elsie’s father chanting: Arrogance! Blasphemy! That’s not how God created me! Pointing at the tiny girl and the others waiting in line, enraged that no one in the hospital was listening. Elsie lifting her own protest sign—Why Do You HATE What You Are?—so she didn’t have to see the girl’s face, because that giant had been compressing her chest again.

The giant was squeezing her right now. She rose from the cot, fought off a spell of dizziness, and dashed out of the room into the cold hallway outside. Across the hall stood a little bathroom, which she stepped into in order to examine herself in the mirror over the sink.

Except the mirror was gone. Someone had pulled the whole medicine cabinet from the wall—recently, judging by the freshness of the broken plaster surrounding the large cavity that had been left over the sink. The cabinet was sitting on the floor with the mirror side toward the wall, as if the mirror had been offensive, as if it had been ordered to stand in the corner.

Elsie noticed deep scrapes on her elbows now, and these tugged more memories free: Congolese men pouring into the town square, rocks being thrown, people yelling. An old woman with her head wrapped in a brightly colored scarf, spitting at Elsie’s father, throwing clods of dirt. Elsie’s mother leaping forward.

“Mama,” Elsie whispered. “What happened to us?”

Elsie was afraid she already knew the answer. There had been another hospital, bright lights. People lifting Elsie onto a rolling bed, the endless floating of drugs in her bloodstream …

She reached for the medicine cabinet, to turn it around, but a sound from down the hall stopped her. It was her father’s voice, deep and soothing, and he was saying, “Elsie, are you awake? Come here to me, girl.”

“Daddy?” she asked, sticking her head out of the bathroom. It was slightly frightening to hear him in the stillness of the basement. She’d been hoping for her mother’s voice, she realized. Or Teddy’s.

“Daddy?” she called again. Elsie was fourteen years old. Calling her father Daddy was beginning to sound childish. Yet that was the only way she’d ever been allowed to address him.

He didn’t say anything else to her, but her father’s voice continued on in a murmur. She followed the sound down the hall and found him in the old storage room, among the props for the Christmas pageant and the Easter decorations, the extra folding tables and chairs, and stacks of out-of-date paper hymnals that had long since been replaced by tablets. The Reverend Mr. Tad Tadd, Elsie’s father, was kneeling in one corner of the room, facing a large plaster Jesus that had once hung on the wall in the room where Elsie had woken up, before one of its feet had fallen off. Elsie had thought the Jesus looked more roguish with one foot missing, and perhaps more historically accurate, considering his injuries on the cross; however, most people were not looking for roguishness or perfect realism in their Savior, Elsie’s mother had explained, and so the broken Jesus had been relegated to the storage room.

Her father, turned toward the wall, was murmuring to himself, with his personal Bible open in his hands. Elsie could catch only a word here and there. He might have been saying, “We are all the fish … You tried to tell me … Fish of different sorts, the fish …” Which made no sense, since her father did not care to eat fish of any kind. And yet he sounded as though he were holding up one end of a quite serious conversation with God.

His hands and arms, like Elsie’s, were scratched, but she could see nothing else amiss from where she stood.

Tentatively, she asked, “Daddy, what are we doing here?” She didn’t like the idea of interrupting, but her father sometimes spoke to God at such length that it wasn’t practical to wait until he was done.

“They never changed the door codes,” her father said,without turning from the plaster Jesus. “I didn’t want to bring you home just yet.”

“But how did we get here?” Elsie asked.

“Joel helped me. We got you released and brought you here so you could wake up in peace.” Joel, a doctor, had been one of her father’s parishioners and his best friend, before the Reverend’s fall from grace.

“But … Tshikapa, the Congo,” she said.

“Yes, Africa,” her father answered heavily. And then, as if to explain, he added, “Airlift and two hospitals.”

Yes. That. The mirage in her head was taking on solid form. The mob, and the rocks.

Elsie had been standing just inside the doorway, but now she got closer. Hoping the words were wrong, she asked, “Mama and Teddy are dead? I didn’t dream it?”

One of her father’s hands went to his face, and when it came away, Elsie could see that it was wet. He was crying. He turned his head slightly as he said, “You didn’t dream it, baby girl.”

She wanted to feel shocked, but she didn’t. Part of her had known the moment she woke up.

Elsie took a seat on an aged footstool with the stuffing coming out of it. A broken hymnal tablet shared the stool with her. When her leg brushed against it, a four-inch-high three-dimensional Japanese woman sprang up from the tablet’s screen, lifted her arms, and began to sing the Japanese version of “Crown Him with Many Crowns.” A crack down the center of the tablet caused half of the woman’s body to be a smudged rainbow of disconnected colors. Elsie switched off the tablet.

“Are they gone?” her father went on. “In a sense, yes. My beautiful wife and beautiful little boy, but—”

“But they’ll live on in heaven at the end of time?” Elsie interjected automatically, because that was the sort of thing her father would say at a moment like this one.

“Yes, they will. But they don’t have to wait, because they are living on already.”

A rock to the back of her mother’s head. Teddy trampled. She had seen those things.

“How?” she whispered.

The Reverend had his forehead leaned against his Bible in an attitude of most fierce prayer, and Elsie wondered if it was possible that he had conjured up a miracle. She imagined a mural of this very moment, herself and her father and God hovering above them in his radiant robes, and she saw the speech bubble above her own head: “Excuse me, Lord God? Have You got something remarkable up those flowing sleeves of Yours?” But the God in the imagined mural looked as curious as Elsie was to hear what her father was going to say.

“If there’s one thing I’ve always said,” the Reverend told his daughter, “it’s that a man who cannot admit he’s wrong is not much of a man.”

It was true, she’d heard him say that, but—

“Do you mean you, Daddy?” she asked.

“I do.”

This surprising admission took several seconds to unfold within Elsie. Her father was criticizing himself?

“What—what were you wrong about, Daddy?” she asked.

In the mural, God gave Elsie a look of disappointment. “You know what he was wrong about, Elsie,” His speech bubble admonished her.

Elsie’s speech bubble said, “I need to hear him say it.”

The Reverend Tadd said, “A revelation, my sweet girl, is like turning on a light or opening a window. Have I told you that?” Elsie still couldn’t see his expression, but she imagined that it looked as it often did during the most ecstatic portions of his sermons—one part joy, one part pain. “You’re in a dark room and then—poof!—the sun floods in. And what you thought were formless shapes and terrible shadows are not. In God’s light, you understand that they’re something else entirely.

“Do you want to know what I’ve been shown?” her father asked. “Should I try to put it into words, even though words won’t do it justice?”

“Sure, Daddy.” If there was one thing Elsie understood about her father, it was that he knew how to use words that would do his ideas justice. His pride in his verbal skill burned intensely. In the mural in Elsie’s mind, she saw that pride like a glowing coal where his heart should be. Her father’s skill with words was the only thing that had buoyed him in the face of his lost ministry, his failure with the church board, his public humiliation. And his skill with words was part of that tight grip the giant had around Elsie’s chest.

“I’ve been shown that my expulsion from the Church of the New Pentecost was fair. I was as wrong as a man could be,” he told her, the words coming out in a toneless stream. “I went on the radio all those years, I stood at the pulpit before my congregation and told them they were defying the Lord. Changing themselves, growing new hearts and lungs and now even eyeballs!” His voice grew more resonant, as if he were in rehearsal for a public performance.

In the mural in her mind, God said, “He impresseth Me greatly with his beautiful voice! At least he’s got that going for him.”

She silently agreed with the Lord; she’d always loved her daddy’s voice. But would he say the things Elsie could feel caged up inside her own chest?

The Reverend continued, “But what if I am the one who defied the holy design? I can still see the look in that boy’s eyes, Elsie, years ago, when I told him he was turning himself into a demon!”

He stood up and reached for Elsie’s hand without turning toward her. Elsie got to her feet and slipped her hand into his. She thought they were going to pray together, but instead he led her out the door and back into the hall. The Reverend moved swiftly, pulling her along in his wake as he walked up the stairs, through the vestry, and out into the church itself. The lights were off, but late-afternoon sunlight came in through the stained-glass windows, turning dust motes into burning stars. He walked to the very edge of the dais, still holding Elsie’s hand, and there he faced the empty pews as if they held a Sunday’s worth of worshippers. He raised his arms toward heaven, and because Elsie’s hand was clasped in his, her arm was lifted too.