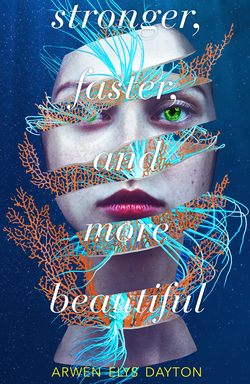

Читать книгу Stronger, Faster, and More Beautiful - - Страница 8

ОглавлениеHuman!

Stop!

… is what I’m thinking. As if I’ve already become something else, a different species, and I’m tired of hearing all of his worn-out, human-person logic.

The man is reminding me that Julia’s heart will be combined with my own heart, so it’s not like I’m “taking” hers. It’s a synthesis. The new heart will fuse both in a way that’s better than either of the originals. A super-heart, I guess you could call it.

He is reminding me of this, and every time I say “But—” he cuts me off by continuing his explanation, only more loudly. Now he’s almost yelling, though he’s just as cheerful as he always is.

Did I mention that he’s my father? And he’s only repeating what my doctor has explained so many times. Although, let’s be honest, my doctor explains the same things very differently. She discusses recovery rates and reasonable percentages and acceptable outcomes. She tells me about other patients, though of course, my case and Julia’s case—the case of Evan and Julia Weary, semi-identical twins—is unique, so we are, as she likes to say, “medical pioneers.” I’ve come to think of us as the season-finale episode of a show about strange medical cases. Tune in for the outrageous conclusion!

I’m in my hospital room, but I’m sitting in a chair in the corner, because it’s dangerous to stay in the hospital bed, which can be wheeled away for CAT scans or blood draws or surgery, or whatever, so easily. You have the illusion of control if you’re sitting in a chair.

Julia is in the adjoining room. She’s on the bed, of course. And though I can hear our mother in there with her, she’s only saying a few quiet words to my sister, and my sister is not saying anything in reply.

“This is fortune smiling on us, Evan,” my father says, using what has become one of his favorite phrases. He looms over me, because I’m sitting down while he’s standing and also because he’s six foot five. “Years from now, you’re going to look back on these weeks and wonder why you ever hesitated. Julia would want her heart and yours to be joined.”

Whenever he senses me becoming skeptical about what we’re going to do, my father finds a new angle to convince me. This is the new angle for today: Julia’s fondest wish is for our twin hearts to become one.

“But I’m the only one who will get to use the heart,” I tell him. “It’s not like we’re turning into one person and sharing it. I get the heart. She gets nothing.”

He raises his voice another notch as he says, “Would you rather put hers in the ground? Alone and cold? To rot?” Even he can hear the hysteria that has snuck into his argument. He lowers the volume to something like normal conversational level and adds, “You know she wouldn’t want that. She does get something. She gets you, alive.”

“I’m the one who gets that!”

“She gets it too, Evan.”

I hope that’s true.

“You sound out of breath,” my father says. “How about we keep our voices calm?”

This is an infuriating suggestion since he’s the one who’s not calm, but his observation is accurate; I’m having trouble catching my breath. I concentrate on forcing air in and out of my chest.

I notice that we’re only talking about Julia’s heart, even though she’ll give me so much more—her liver, part of her large intestine, her kidneys, even her pancreas. It’s too depressing to keep mentioning all the pieces of both of us that aren’t working right, so my parents and I have begun using the heart as a stand-in for everything.

I look up at him wearily. “Dad, why do we keep talking about it, anyway? You already decided.”

“You decided too, Evan.”

I sigh, and though I try to sound as angry as possible, he’s right. I did decide.

When the nurses show up to do tests, my father leaves. He doesn’t like to stick around for the nitty-gritty, which used to annoy me but now is a relief. If my father is present, he considers it an obligation to insert as many positive comments as possible into whatever uncomfortable hospital procedure is happening. It’s not ideal to have to make appreciative noises about the weather and baseball scores when a male nurse is putting a catheter into your penis, for example.

With my father gone, I hardly have to say anything.

Nurse: “Does that hurt?”

Me: “A little.”

Nurse: “Is this better?”

Me: “A little.”

Nurse: “Can you roll over onto your back now?”

I don’t even have to answer that. I just have to do it.

Later, I’m left alone in my hospital room. This is the last day. It will happen in the morning. Julia and I have just barely made it to our fifteenth birthday. And now comes … whatever is next.

I am not immune to daydreams. I imagine slipping on my clothes, walking out of the hospital, and asking my mother to bring me somewhere peaceful to die. My favorite fantasy locations are on a beach overlooking Lake Michigan, or on the moon base, while staring up at the small blue face of Earth.

Yes, I know there isn’t any moon base, but I’m not sneaking out of the hospital either.

The daydreams are tempting, but here’s the truth of it: death sucks more than life, almost no matter what. There. I’ve admitted it. I want to live. Blech. It feels wrong.

I get off my hospital bed and go into the connecting room, Julia’s. My heart races as soon as I’m on my feet, but if I move slowly, I can keep it from getting out of hand. Julia’s room is kept nice and quiet and mostly dark, though it’s still daytime, so cloudy light comes in through the slatted blinds over the window. Her ventilator hisses and clicks. Her bed is surrounded by IV stands that are providing her food, her water, her drugs. Dripping, dripping, dripping away.

“Hey,” I say, out of breath when I reach the edge of her bed.

Hey, she says. Not out loud, of course. But I know she says it.

Julia is gray and her cheeks are hollow, but she’s still beautiful. Her hair is red, like mine, but hers is much longer and it’s been fanned out across her pillow (by our mother, probably), as if she’s posing for an illustration in a book of fairy tales. Here is Snow White, awaiting the kiss of a prince to wake her. Here is Sleeping Beauty, for whom the rest of the world has been frozen. I slide myself onto the bed next to her and lie there as my heart and lungs slow down, listening to the sounds of the machine that is breathing for her.

“Hey,” I say again.

It’s so boring here, she tells me quite clearly, though, again, not out loud. The time when Julia can speak out loud is over.

“I’ve realized that being a medical pioneer is mostly about surviving the boredom,” I tell her.

Julia sighs, silently of course. Then she tells me, When the doctor calls us that, I imagine us in a covered wagon with one of those old-timey black doctor’s bags.

“Why do people think being a pioneer is good?” I wonder aloud. “Isn’t it better to be waaay at the back of the line, after all the kinks have been worked out?”

This is going to sound mean, Julia tells me, but I never even liked real pioneers. In those Little House books, I kept wondering why they didn’t stay in New York or Chicago, where all the fun stuff was happening.

“You’re a snob,” I tell her. “They were brave.”

Yeah, they probably were, she admits. Then: You’re going to be brave too, Evan.

“Yuck. You sound like one of those greeting cards with the fancy cursive.”

I got sappy there for a second. Sorry. It’s from being in the hospital. She changes the subject. Where have you been all afternoon?

“Tests. Oh—this is exciting—they took a sample of my poop. New test. I guess it was to see what my large intestine is doing.”

What were the results of this poop test?

“It was poop. They confirmed that.”

Well … that’s a huge load off my mind, she says.

“After the test they plopped me back onto the bed.”

I’m flushed with relief that everything’s okay.

“It would have been so crappy otherwise.”

We both laugh. Me out loud. Julia, you know, not out loud. Annoying puns are kind of our thing. I scoot over until my head is against hers.

I forget what that’s like, she says.

“What? Tests?”

Moving.

“Oh. Right.” Even though I’m here with her so much, sometimes I forget too.

We’re both quiet for a while, but I know what Julia’s thinking about. She’s remembering that time when we were five years old, and she beat me twenty-four times in a row running down the street outside our house. I can feel her gloating.

I tell her, “Look, you beat me that one time—”

It was twenty-four times, Evan.

This is an old argument.

“Fine. You beat me on that one day. But I never let you beat me again,” I remind her.

What neither of us says is that we didn’t have many races after that day when we were five. Running became too difficult for either of us, and the following year, it was apparent that very few of our organs were growing at the proper rate.

Relax, Evan, she says. You’ve won forever now.

I don’t answer her because that’s a horrible thing to say. If we were having one of our competitions to see who could say the most despicable thing, she would totally win.

Oh shit, are you crying? I didn’t mean it. I was only joking!

I put my hand over Julia’s heart, and then I put Julia’s cool, limp hand over mine. It’s possible that I am crying, but there’s no reason to dwell on it.

In that calm way of hers, Julia tells me, We shared a womb, Evan, and a crib, and a room for the first six years of our lives. Now we’ll share more things. It will be okay.

Possibly you have never heard of semi-identical twins, so let me explain. Semi-identicals happen when two sperm fertilize the same egg. (I really hope you already know what sperm and eggs are, because I don’t want to be the one who has to tell you.) At some point after this cellular three-way, Mother Nature realizes that something is not right, and the egg splits into two, which in our case meant that it split into me, Evan, and her, Julia. But it’s not quite as simple as that. There are some mixed-up DNA signals with semi-identicals. Some become intersex (boy parts and girl parts), and some have other glitches in the embryo-formation process. We had none of those issues—our problem is that our hearts and livers and several other organs never learned how to grow to full size, even though the rest of us made a go of it.

I’m taller than you are, Julia helpfully points out as I float toward sleep.

She’s taller by about an eighth of an inch, by the way. Fifty percent of our DNA is identical—from the egg we both shared.

And the other fifty percent, from the sperm, is not identical, but it comes from the same person (our father, unless our mom has really been hiding stuff from us). So we’re as closely matched as any boy and girl can be.

But around our thirteenth birthday, Julia’s organs started lagging behind worse than mine did. At first, for months and months, she was just tired. Then she was just asleep. Then it wasn’t really sleep anymore, and she was in the hospital and the machines were brought in to keep her alive. And now she is on this bed, silent to everyone but me. Vegetative is what they call it, as if she is a stalk of wheat or a spear of asparagus. This sucks so deeply that there aren’t really words. This is as close as I can come:

That’s me in the middle, drowning.

I fall asleep next to Julia and I wake up when I hear voices in my own room. At first I think it’s nurses who’ve come to give me a second rectal exam—just to make sure—but that’s not who it is. It’s my mother, and a man—not my father. This man has a different voice entirely, smooth and deep and sort of … stirring, I guess you could say. Except that he’s using it to argue with my mother, and almost immediately I know exactly who the voice belongs to.

Don’t keep me in suspense! Julia says, startling me. I didn’t think she was awake. Who is it?

“It’s that weird minister Mom’s been talking to all month. I’ve heard his voice when she’s talking to him on the phone.”

Oh, yeah. She keeps mentioning things “the Reverend” says. I didn’t even know we were Christian until Mom started having all these Jesus feelings.

“I’m not sure Reverend Tadd even is Christian,” I whisper to her, still trying to hear what they’re arguing about.

His name is Reverend Tadd? Julia asks skeptically. Is that his first name or his last name?

“I don’t know. But I do know that he’s an asshole. The way he speaks—it’s like Jesus was his roommate at summer camp and if you’re lucky he’ll introduce you.”

How does Mom even know him?

“She wanted someone to ‘guide her to the right choices’—about us, I guess. I heard her tell Dad. They argued and Dad won, but Mom said she still needed to talk to someone. And talking people out of medical procedures is, like, Reverend Tadd’s thing.”

“Wait! You look angry.” Our mother’s voice rises suddenly on the other side of the door. “We’ve had beautiful discussions, and I said you could come bless them, but I don’t want you to argue—”

The door from my room to Julia’s room flies open a moment later, and the man is in the room with us, trailing our mother. He approaches the hospital bed, one hand raised, with a finger directed upward, as if he has a personal, finger-pointing connection straight to heaven and he’s calling in a favor.

“You!” he says, his eyes locking onto me where I lie next to my sister. I’m not ashamed to say he’s scary, because he is scary; his eyes are wild and his face is screwed up with outrage, but he’s also …

Much younger and better-looking than I thought he would be, Julia says calmly.

That’s exactly what I was thinking. The Reverend is young, perhaps only in his late twenties. He has thick, wavy black hair that falls over his forehead, and piercing dark eyes that are alight with passion.

Before our mother can stop him (which, to be honest, she is making only a very feeble attempt at) he’s on his knees at the side of the bed, his eyes beseeching me. I’m startled by his sudden presence, but it’s hard to be too startled when Julia is with me.

“You,” he says, bowing his head over his hands briefly, as if to let me and Julia know that he’s not too proud to beg—in fact, that he relishes this opportunity to beg.

“Reverend,” our mother says, without much force. “It’s been decided. And this is family business.”

Ignoring her, he looks at me and says, “You know there’s still time.”

I should be cringing away from him, but I’m so tired of the sympathetic looks from nurses and my parents that his energy fascinates me.

“Time for what?” I ask him, propping myself up onto my elbows.

Don’t ask! Julia says. She has understood immediately what sort of man he is. Why would you encourage him?

“Time for ev-er-y-thing.” (That’s exactly how it sounds.) “You’re a young man now, a person.” He’s gripping the railing of the bed in his zeal. “If you do this thing, Evan Weary, you will become something that’s not meant to be.”

His voice and his certainty are mesmerizing. I feel as though he has pressed something sharp into my malfunctioning heart. The Reverend Tadd-not-sure-if-it’s-his-first-or-last-name sees that he’s gotten to me, and he follows up immediately.

“Do you want to turn yourself into a demon? A life-devouring creature?” he asks me, his face getting close enough to mine that his minty breath washes over me. “Is that your goal?”

Do you know the sensation when you’ve been injured but the pain hasn’t reached you yet? I am having that feeling now. I think it was his use of the word life-devouring.

I know resistance is called for. “Um … I don’t know if I even believe in demons—” I begin, but he rides right over me.

“You don’t want to be one! That’s the answer. No good person wants that!”

I can feel Julia’s outrage that I’m taking these insults lying down. Roll over and kick him in the nuts! she tells me.

But I don’t have to, because our mother has finally found her courage, and she grabs the Reverend Tadd by his shoulders.

“You have to leave now,” she tells him, her voice quaveringbut firm. When he doesn’t budge, she puts her hands on her hips and says, “If you don’t leave, I will call the nurses—and security! I mean it, Reverend.”

He stands up, unrushed, as if he were done anyway and is leaving only because it’s his own choice. He brushes off his pants and stares down at me and Julia, calmer now that he’s succeeded in calling me a demon—or, I guess, a soon-to-be-demon. The full demonification hasn’t happened quite yet, as he has thoughtfully pointed out.

“Reverend!” our mother says, warning him against further pronouncements.

Close-lipped, Reverend Tadd walks to the hospital room door, yet before we’re rid of him, he looks back at me and takes another stab. “You don’t have to do this selfish thing,” he says.

Selfish. It’s the word that’s always there, in the back of my mind. How did he know?

Sensing that I have become paralyzed before this man, Julia steps in. Can’t you see it’s already eating Evan up? she yells at him. If Jesus were here, He’d slap you! You—you—creep!

But Reverend Tadd, of course, has not heard her, and he’s already left the room.

“I’m so sorry, Evan,” our mother says. “I said he could say a prayer here, that’s all.” She’s leaning against the closed door and has dissolved into tears, which, actually, has been her most common state over the past few months.

What’s Mom crying about? Julia asks, still half yelling. She’s the one who let him in here. Oh, Evan … are you crying too?

I wake up and know that my parents have tricked me, or rather, that they had the nurses drug me. I’m in my own hospital bed, even though I don’t remember moving back. Sunlight is pouring in my window. It’s morning. The Day.

“Julia,” I say as my eyes open.

The room is full, but empty of her. Nurses are crowding in with prep carts and rubbing alcohol and IVs. They’re checking my vitals, slipping tubes into my veins, talking to me with that impersonal friendliness they must learn in nursing school.

I catch sight of my father, so tall that it feels like he’s in the way, even though he’s standing in the corner to stay clear of the bustle. He smiles benignly at me.

“It’s okay, Evan. She’s gone on ahead of you.”

“Julia!” I say again, louder this time.

The nurse closest to my face makes little noises that are half shushing, half consoling. Well, mostly shushing.

I hear Julia very distantly. Evan. Evan. That’s all there is, only the ghost of her voice from somewhere far below me in the hospital. Evan …

It is … I’m not sure how many days later. Maybe four?

They took Julia’s heart while I was unconscious, and then, inside my chest cavity, they used her “compatible tissue” to rebuild my own heart, and then they jolted the super-heart into action, and (I heard later) they all clapped when it began pumping blood. Pictures were taken. A day later they did the kidneys, the liver, and everything else that required renovation.

I have a line of metal staples down the middle of my chest. They look pretty badass, like Dr. Frankenstein was given free rein to close me up. There are stitches and staples in lots of other places too. Supposedly, modern medicine is excellent at minimizing scars, but my nurses assure me that mine will still be amazing after they heal. I’ll look like a scattered train track for the rest of my life. It feels like the train on that broken track hit me, then backed up to finish the job. Except … even with all the pain, I actually feel better. My heart is beating strongly and regularly, my body seems lighter. How crazy is that?

“Here I am,” I say.

The hospital room is empty except for me, so I can get away with talking to myself without drawing frowns from the nurses. I lay a hand across the mess of staples down my breastbone. “And here you are,” I tell Julia. “Keeping me alive.”

She doesn’t answer. It’s rainy today, and the only response I get is the patter of raindrops on the hospital window. Even if you’re one of those people who love the rain, I think you’ll agree that the things it says are, at best, extremely boring. At worst, they’re only raindrops, which are no substitute for your dead twin sister.

“Dead,” I say, trying out the word that I haven’t let myself think. I’ve shied away from it since the operations. Now that I’ve said it aloud, though, I have to ask her what I’ve been afraid to ask.

“Julia, were you dead when they took out your heart? Or did I steal it from you while you were still alive?”

She doesn’t answer. Of course, she doesn’t need to. Everyone—the doctor, my parents, the nurses—danced around this question. But I always knew the truth.

I am growing again.

It’s been twelve days since the last surgery and there’s enough oxygen in my blood, and my digestive system actually gets nutrition out of the food I eat, and and and and, you know, all the things the doctor optimistically suggested would happen, are happening. I’ve grown an eighth of an inch and gained three pounds. That eighth of an inch, by the way, makes me as tall as Julia was, though I’ll keep growing, they assure me. I might even get as tall as my father.

“Fortune has been smiling on us all this time, Evan,” my father is saying. Did I mention he was in here with me? He is. He’s helping me get into my clothes. I’m strong enough to dress myself, but I’m letting him feel useful.

My mother’s here too, though she’s outside the room, to give me privacy while I get dressed, and probably also because she feels guilty about letting Reverend Tadd crap all over the last few minutes I had with my sister.

They’re releasing me from the hospital today. Over the past several years, Julia and I have spent a combined total of over five hundred days here. During those five hundred days, I’ve imagined this final day many times. In my favorite version, we walk out the front doors, and shortly afterward, the hospital is leveled by an earthquake, and then ripped apart by a tornado, and then set on fire by roving bands of zombies. After that, if “fortune keeps smiling on us,” packs of wild dogs will urinate all over the rubble as a warning never to rebuild.

“It’s nice to see you smiling, Evan,” my dad says, when my head emerges from the sweater he’s pulling into place over my Frankenstein torso.

I decide to let him in on the daydream. “I was thinking that after we walk out of the hospital’s front doors—”

“You know we’re going to wheel you out in a wheelchair, right? No walking just yet. But soon!” he tells me cheerfully.

“Oh, right,” I say. He is so literal.

Every doctor and nurse on this floor is lining the hallway as I’m wheeled toward the elevator by my parents. Even some of the more mobile patients are standing in their doorways to watch us, the medical pioneers. My father waves and smiles at all of them. My mother is soundlessly mouthing thank you, as though she were always one hundred percent behind this whole cannibalize-your-sister’s-organs scenario.

I’m dying to hear what Julia would say about this sad parade to the elevator. Would she tell me to feign a stroke? Or clutch my heart?

“That’s right, smile,” my father says quietly. “Let them see how grateful you are.”

Am I grateful? I haven’t heard her voice for two weeks.

In the main lobby, and the world outside is visible through the huge glass doors. My mother’s gone off to pull the car around, and when we see her driving into the pickup area, my dad says, “Here we go,” and pushes me out through the doors.

“Oh!” I cry out, because the strangest thing happens the moment I cross the threshold: the super-heart stops. There’s a heartbeat, and then there is nothing, stretching out from one instant to the next and the next and the next. I cannot breathe, I cannot move. My super-heart has walked off the job without giving notice.

My father’s smile falters, and then, in a panic, he shakes me. “Evan? Evan! Is it your heart?”

There’s a thunk! in my chest as the heart starts up again. Then, thump-thump, thump-thump, it’s going—as if nothing at all went wrong. If anything, I feel a new surge of vitality.

“Evan?” he says again, frantically.

I wave him away. “My heart … is fine,” I tell him.

“Are you sure?” He looks back through the doors, ready to flag someone down.

I nod, give him an emphatic thumbs-up. My mother has pulled the car up right in front of us, so I push myself to my feet, and before he can even catch up to me, I’ve opened the back door of the minivan and climbed inside. In moments, we’re all in the car and my mother is driving away.

I watch the hospital growing smaller as we get to the end of the street. When at last I can see only a sliver of the hospital’s upper floor above neighboring buildings and it’s about to disappear from sight entirely, I think, Cue the earthquake!

Julia should laugh at that, but she doesn’t. I’m sitting in the back of the minivan alone, looking past my parents at the road ahead. Traffic and life are out there, ready to take me in.

It’s not until we are stopped at a long traffic light that I hear it. Very quietly, a voice asks, Do you want to kill all the other patients? The voice sounds not so much upset as curious, and it’s as soft as the murmur of an insect or a mouse.

I’m so startled, so unsure of what I’ve heard, that I can only bring myself to whisper an answer. “I don’t mind if they’re all evacuated first,” I breathe. “But the building has to go.”

There’s silence in response and I sit there, holding my breath. I’ve imagined the voice; it’s nothing but my hopeful ears playing tricks on me. The quiet stretches on as we travel through the city. My ears strain for anything besides the noise of the traffic, and they are disappointed.

But when we’ve gone a very long way and the hospital is nothing more than an anonymous mass far behind us, I hear this:

I agree. The hospital building has to go. The voice is growing as it speaks. It’s not a mouse’s voice anymore, it’s a kitten’s. So …, it says, growing into a child’s voice, what were the results of the operation?

“Just the usual,” I whisper, for fear of scaring her away. “You know, new heart, liver, pancreas, blah, blah, blah.”

No new brain? she asks. Her voice has become her real voice.

I shake my head.

So they screwed up the one thing you actually needed?

I nod. And smile.

Did you hear about that kid who was taken into the operating room, but then he had a change of heart?

“He didn’t know if he was going to liver die,” I whisper.

Aorta laugh at that.

“Like me—I’m in stitches.”

I don’t mean to cry, but tears spring to my eyes and a bunch of them are pushed out by a sudden burst of laughter that is incredibly painful to all of my recently sutured parts, which doesn’t make it any less magical.

“You were so quiet,” I whisper.

That was on account of being dead, she tells me. By the way, I heard you call it “your heart.” That was a little cold.

“I didn’t mean it,” I say, squirting out another set of unstoppable tears. “I meant our heart.”

I’ve said this last part loudly, and my father and mother both turn back to look at me.

“Our heart!” I say again to her.

“That’s right, Evan. Our heart,” my father says.

Is he serious? Julia asks. Are they going to take credit for everything forever?

“Probably,” I answer.

Julia sighs. Eventually she says, I guess it doesn’t matter what they think. What do we care?

There.

She has said it: we.

And I am happy.