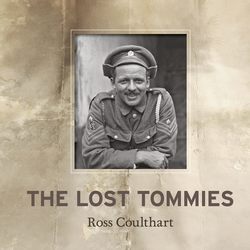

Читать книгу The Lost Tommies - - Страница 10

Identifying the Tommies

ОглавлениеPLATE 36 A sad soldier of the Royal Fusiliers – a close-up from the high-resolution scan of his fatigued face shows him lost in thought. This same soldier also appears in Plate 216.

In February 2011, the Australian Channel Seven TV Network aired a documentary about the discovery of the Thuillier glass plates. Shortly after that ‘Lost Diggers’ story was broadcast, we posted thousands of the Thuillier collection photographs of the Allied soldiers on the programme’s website and also on a specially created Facebook page, which still exists today. It became an unprecedented social media phenomenon for a history archive, with millions viewing the pictures online from all over the world. Within days, the volume of emails, excited phone calls, letters and Facebook messages we were receiving showed just how much the images had touched so many. Hundreds of thousands of viewers wrote us emotional and passionate accounts of their response to the faces of the Australian diggers and British Tommies in particular:

Goose bumps watching the show …

This is so wonderful, I can barely believe it’s true. Many of the faces showed signs of great fatigue and yet they managed to smile and pose for a photo forever preserving the moment in time …

A few tears shed knowing some of these fellows never made it home. What a wonderful discovery for many families around the world.

For so many of the people who have since viewed the photographs online it has become a personal odyssey to find a connection with the as yet unidentified soldiers:

These photos brought tears to my eyes. I had eight great uncles who all fought on the western front. Five of them were brothers. One of them was killed in action five weeks before Armistice Day, after surviving three years of that bloody hell. He is our only Digger out of eight that we have no photographic record of. Maybe he is one of these men.

Thank you so much for making these great photographs available. My mother lost her uncle in France in 1915. We have no info’ on him, not even a photo. We have always tried to find his records but without a regiment number, we are up against a brick wall. I sit here with tears in my eyes, wondering if he is one of these brave men. You have done a wonderful thing.

Our grand uncle … died of wounds … How amazing to think his image could be among these photos.

I carefully examined each and every photo looking for any resemblance to the many family members who fought in WW1, some of whom never returned.

Then began the calls for the Australian images to be brought home:

Don’t let them be forgotten. Bring these historical plates to their rightful home.

These photos … should be treated as national treasures and every single one of them should be brought home immediately.

These young men gave their lives in order to protect and fight for our country; these photos are an amazing part of the history of Aussie diggers in battle and the campaign they were involved in … Lest we forget.

Many relics of these men may remain in France but these treasured photos need to be honoured on Australian soil. It is now our turn to answer the call of duty and return these photos to their home for safekeeping.

Ohh I have tears of pure joy and total sadness after looking through these pics … History in front of our very own eyes … Thank you for sharing. Never forgotten.

In July 2011, with the generous support of the Seven Network’s chairman, Kerry Stokes AC, the entire Thuillier collection of around 4,000 glass photographic plates, including the British images, was purchased from the living descendants of Louis and Antoinette Thuillier, the couple who had supplemented their farming income during the First World War by selling pictures to passing Allied soldiers. If Louis and Antoinette were alive today they would no doubt be chuffed and probably very surprised to see just how much passion their portraits of thousands of young soldiers from a war so long ago has aroused.

PLATE 37 An equally sad-looking soldier – no regimental badge.

In late 2011 the precious glass plates did finally ‘come home’, in a gigantic packing case, purpose-built to carry them, along with the Thuilliers’ canvas backdrop. After months of planning, cataloguing, careful cleaning and scanning, the Australian digger plates were gifted to the Australian War Memorial for permanent display. Many of the more intriguing images and the stories behind them formed the basis of a nationwide touring photographic exhibition organized by the AWM. The remaining thousands of British and other Allied soldier plates have been preserved by the Kerry Stokes Collection in a secure repository in Perth, Australia.

More than once in our research it has struck us how impermanent many of the records that we rely on today are in comparison with the handwritten files, letters, printed photographs and glass photographic plate negatives that have made this such a rich collection. As we began examining the plates, drawing on the expertise of people like Peter Burness, it was a revelation to discover how, in many ways, the photographic plates used by the Thuilliers are actually a superior storage medium to the standard celluloid photographic negative, let alone digital imaging. Not only have they already lasted nearly a century, but so much information is packed into these enormous negative plates that it was often possible for us to zoom in on a colour patch, medal ribbon or cap badge to help identify a soldier. There is something terribly poignant about being able to zoom in to the pained and weary eyes of an individual soldier – actually to see the mud on his boots and the texture of his uniform.

As we applied modern photo-processing software, it was astonishing to see faces emerge from the murk of so many plates – images that could so easily have been lost forever. We have asked ourselves many times how much of today’s history will survive to the same extent. How many personal handwritten letters have we preserved today that will record the thoughts and experiences of our loved ones for future generations to read? What was once recorded in a letter just a few decades ago is now just an electronic impulse stored on magnetic media whose lifespan can still currently only be surmised. Will the digital records of today – the photographs, emails and the writings on other online ephemera such as Facebook, Twitter and websites – allow people in a hundred years to explore the history of our present era with as many resources as remain from the First World War? How much of our heritage and experiences will be lost as contemporary storage media slowly fade or are carelessly deleted?

The process of identifying, at least by regiment, as many of the Thuillier images as possible for this book has been a painstaking and often frustrating process. Many of the soldiers were photographed in front of the distinctive painted canvas backdrop and that has been a useful fingerprint in identifying Thuillier pictures which made their way back home into family collections or regimental history books. On rare occasions the identification was easy because a particular soldier features and is actually named in one of the rare Thuillier images reproduced in regimental history books or contained in personal collections. There have been other occasions where photographs taken of soldiers after the war have allowed us to ‘match’ them with a soldier in a Thuillier image (see the Royal Fusiliers). Once identified, it has also been difficult to find out more about a particular soldier because so many of the British service files are incomplete or were destroyed completely in German bombing raids during the Second World War.

PLATE 38 An unidentified soldier. No clues as to his regiment can be seen in the photograph.