Читать книгу The Lost Tommies - - Страница 6

Prologue

Оглавление… average men and women were delighted at the prospect of war … the anticipation of carnage was delightful to something like ninety per cent of the population. I had to revise my views on human nature.

Bertrand Russell, on 1914 2

There was a time before, and, for those who survived, there was a time after. But for generations of men and women, the cataclysm of the First World War left a raw emotional scar, a legacy of loss and tragedy that still lingers today. It is difficult to comprehend one century on just how readily so many young men clamoured to go to war. The patriotic fervour that followed the declaration of war in August 1914 may seem quaintly naive today but for many of the men rushing to enlist the biggest fear was that the fighting would all be over before they got the chance to teach the Germans a lesson.

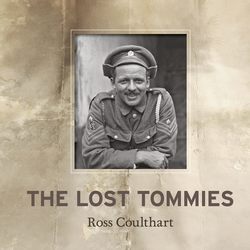

PLATE 1 A soldier from the 7th or 8th Battalion, Leeds Rifles. They were part of the West Yorkshire Regiment – he wears the West Yorkshire shoulder badge.

On 4 August 1914 thousands of men already serving in territorial reserve regiments, including those with the Prince of Wales’ Own West Yorkshire Regiment, received the long green envelopes marked ‘Mobilization – Urgent’. Recruitment offices were also overwhelmed by young men rushing to enlist, willing to do their duty for King and country; a flood reaching 30,000 a day at its peak.

I went to Bellevue Barracks, home of the 6th West Yorks, a Territorial battalion, and found there were crowds round there. Everybody was excited and every time they saw a soldier he was cheered. It was very patriotic and people were singing ‘Rule Britannia’, ‘Land of Hope and Glory’, all the favourites. A challenge had been laid down over Belgium and they were eager to take it up. I should have been home at nine but I stayed there until late at night. Everybody stood in groups saying ‘We’ve got to beat the Germans’ and quite a number were already setting off to enlist.3

Few anticipated the horror of what was to come. But the survivors would never forget it. George Morgan was one of the first volunteers for the West Yorkshires. When he admitted to the recruiting sergeant that he was only sixteen, the sergeant advised him to go outside, come back and tell him something different. George returned with the implausible claim that he was now in fact nineteen; he was then sworn in to service.

It was the biggest incident in my life. I’ve lived sixty years afterwards, and I’ve never, never got over it. It’s always been there in my mind. It was the biggest thing that ever happened to me. We’d all got to know each other very well and we were all very good comrades, in fact I don’t think there’s ever been better comradeship ever … and then all at once when this day, this terrible day of 1st July, we were wiped out.4

Just two years into the war, on that first day of the Battle of the Somme, 1 July 1916, it was one battalion in particular of those eager West Yorkshires, the 10th, that was to earn the dubious distinction of having suffered more casualties on that dreadful day than any other British Army unit. Twenty-two officers and 688 men were either killed or wounded, from a unit normally 1,000-strong; more than two-thirds of the men failed to answer the roll call the following day. During the months the Battle of the Somme raged, some one million men from both sides of the conflict combined would be either killed or wounded – and for little discernible gain to either side.

The West Yorkshires was just one of dozens of regiments that went over the top on the first day of the Somme – over 20,000 British soldiers would die in that first twenty-four hours alone; there were 57,470 casualties. Such losses are so overwhelming in their magnitude, so great was the industrial scale of the slaughter, that one can sometimes overlook the fact that each of those broken bodies was a father, a son, a brother, a lover or friend.

Throughout the war, in a quieter corner of Picardy just behind the Somme front lines, soldiers from regiments like the West Yorkshires enjoyed brief respites from the conflict. It was in the small village of Vignacourt that thousands of soldiers met a local French couple who dedicated themselves throughout the war to photographing the soldiers – partly to supplement their income but also because they no doubt realized the profound historic significance of what they were witnessing on their doorstep. They were civilian amateur photographers Louis and Antoinette Thuillier and, as battalion after battalion visited their village of Vignacourt, the couple captured images of the men (individually and in groups) before they were once again thrown back into the trenches, all too often to suffer grievous wounding or death. Among the pictures taken by Louis and Antoinette is the one below featuring members of the 6th Battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment.

PLATE 3 Soldiers of the 6th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment in Vignacourt while they were billeted in the area from early April 1916 through to 9 June.

One of those West Yorkshiremen photographed was a young Bradford man, Walter Scales, a twenty-year-old clerk when his 6th Battalion West Yorkshires was mobilized. He was an officer – barely out of his teens – in a proud territorial unit made up largely of volunteer city workers like himself. Walter looked so young when he joined up that his brother officers called him ‘the Babe’. Within weeks of this photograph being taken by the Thuilliers, he was to lead his men into the horrors of the Battle of the Somme.

PLATE 2 Close-up of Captain Walter Alexander Scales, 6th Battalion West Yorkshires.

For all the troops, Vignacourt was a welcome relief from the front line. A 6th Battalion history records the eight weeks the unit spent training and resting in and around Vignacourt as one of the happier times the battalion enjoyed throughout the entire war:

If we looked at this Vignacourt period from the point of view of the official War Diary we should dismiss it in a few words, something as follows:- ‘Training carried on vigorously: Battalion and Field Days weekly: Reinforcements of three officers and 170 other ranks received in May: two officers and 100 other ranks provided for work on New Railway Sidings at Vignacourt; battalion provides Brigade Head Quarters’ Guard every fourth day, etc, etc.’ The War Diary would thus compress the life of eight weeks into as many lines, whereas a few lurid hours in the Leipzig Salient on July 15th would fill a page. Most of the members of the Battalion would reverse the emphasis, however, and become eloquent on a joy ride to Amiens: a favourite estaminet at Vignacourt: an anniversary dinner: a jolly billet; and they would dismiss the affair in the Leipzig Salient with a shrug, as hardly being worth mentioning in comparison.5

There were also the ‘bombers’ of the West Yorkshires, who arrived in Vignacourt on 5 April 1916 for a well-earned rest from months of fighting. Among them were Bernard Coyne, John Bannister and Harry Duckett. The bombers were a unit of men specially trained in the use of hand grenades, a form of warfare that required close and bloody fighting at the sharpest point of the front lines. These men knew their odds were not good going into the coming Somme offensive. Two of that trio would fall within weeks; the other would almost make it through the war, only to fall in its final few weeks.

PLATE 4 Bombers of the 1/6th Battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment in Vignacourt during their eleven days in the area from 5 April 1916.

PLATES 5–7 1/6th West Yorkshire bombers Bernard Coyne, John Bannister and Harry Duckett.

For eight weeks the West Yorkshires took their rest and training in Vignacourt but they knew what was coming. One history records that the men came to regard their time in the village as their ‘fattening up for the slaughter’.6

Within possibly just days and certainly weeks of his photograph being taken in Louis Thuillier’s farmyard (Plates 8 and 9, below), Second Lieutenant Cuthbert George Higgins, the smooth-faced young officer sitting in the middle of the men of C Company from the 6th Battalion of the West Yorkshires, was dead. Higgins was a Londoner from Hanover Square – his father, William, is listed in the 1901 census as clerk to a brewing company – and it is not clear how his son came to be commissioned with the West Yorkshires. Within hours of the beginning of the Battle of the Somme, on 1 July 1916, the twenty-four-year-old was killed in the British Army’s massive attack on the town of Thiepval. Assaulting the town required the breaching of a maze of trenches heavily protected with a huge number of machine guns, across an open and exposed no man’s land. Higgins was in the reserves, waiting in Thiepval Wood to follow the leading waves of troops that had gone over the top at 6.30 a.m. When the order finally came at around 3.30 p.m. for his company to advance, logistical failures meant the 6th Battalion had to go over alone:

It is a misnomer to say they attacked Thiepval, for not a man got more than a hundred yards across No Man’s Land. ‘The men dropped down in rows, and platoons of the other companies following behind remained in our lines, as to do anything else was suicide. It is impossible to describe the angry despair which filled every man at this unspeakable moment. It was a gallant attack,’ said the Brigade Diary, ‘but could not succeed from the first.’ The enemy’s parapet was alive with machine guns. Again and again attempts were made to climb the parapets and advance, but all in vain, those who succeeded in reaching No Man’s Land only added their bodies to the pile of dead and dying. The 1/6th was the only Battalion of the 146th Infantry Brigade which succeeded in obeying the orders to advance, with what result has been described – every third man in the Battalion had become a casualty – the results were nil!7

PLATE 8 Close-up of Second Lieutenant, C. G. Higgins, C Company, 6th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment, taken during the battalion’s eight-week stay in Vignacourt from April to June 1916.

PLATE 9 West Yorkshire Regiment 6th Battalion soldiers, probably from C Company under the command of then Captain R. A. Fawcett (seated, second row, second from left). The officer first from left is a Lieutenant Hornshaw. The officer third from left is Second Lieutenant C. G. Higgins.

It puts the war’s appalling losses in some perspective to pause and consider that toll; one-third of this one small battalion, men whose faces are probably among these Thuillier images, was wounded or killed on the very first day of the Somme … so many casualties in just one day of fighting, in a war that was to last for years.

PLATES 10–12 Young soldiers of the West Yorkshire Regiment just before the Battle of the Somme – a final few days’ rest in Vignacourt before the Big Push.

Almost a century later it is easy to imagine that the ghosts of these lost Tommies still linger in the ancient French farmhouse where these photographs were taken. On a bitterly cold winter morning, above the very farm courtyard where thousands of young soldiers posed, I am stumbling up an ancient wooden spiral staircase on the last leg of what has been an intriguing historical detective story chasing the clues in the Thuillier images. Each step takes me further back in history, through the detritus of a family home stretching back generations. The wobbly and uneven steps are layered with dust, and I have to steady myself against the crumbling plaster and brick walls. I feel my way in the murky gloom as I step into the attic of this old farmhouse.

The attic is a long, dusty, oak-floored room. Although I am wrapped against the bitter cold of a French winter, the biting chill still penetrates the gaps in the eaves and walls. We move aside old leather suitcases, saw blades and bottles, a stack of empty salvaged Second World War American jerrycans; in one corner is an elegant, perfectly preserved nineteenth-century baby’s carriage with large painted cast-iron wheels. Above our heads the knots of old tree limbs can still be seen in the hand-chiselled oak beams supporting the heavy tiled roof.

My breath is visible as condensation in the frigid air. There is only the sound of feet shuffling up the stairs behind me, and the muffled noise of the occasional vehicle outside. We are all mute with anticipation. It scarcely seems possible that this decrepit attic could be, after months of searching, the place where a treasure trove of extraordinary First World War photographs has lain hidden. There are mounds of old motorcycling magazines from the 1930s that we carefully lift aside, peeling back the decades of a family’s jumble. Everything is covered in a thick layer of dust.

Then, by the light of an attic window, we see three old chests.

I lift the lid of one of them, a battered ancient metal and wood chest. And there they are: thousands of glass photographic plates – candid images of First World War British soldiers behind the lines. There were also Australian, New Zealand, Canadian, American, Indian, French and other Allied troops.

PLATE 13 The battered chests in which the glass plates were stored. (Courtesy Brendan Harvey)