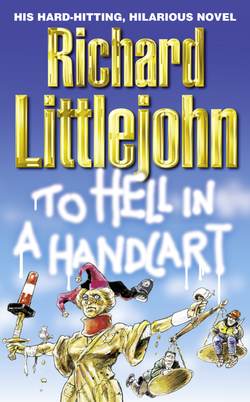

Читать книгу To Hell in a Handcart - Richard Littlejohn - Страница 11

Five

ОглавлениеNow

‘You’re listening to the Ricky Sparke show on Rocktalk 99FM. Let’s go to George on line one. Morning, George. Good to have your company today. What can we do for you?’

‘Hello?’

‘Hello.’

‘Can you hear me?’

‘Loud and clear, George.’

‘Er.’

‘Fire away, George. We’re waiting.’

‘You can hear me?’

‘Yes George. You’re live on air.’

‘Is that you, Ricky?’

‘No, it’s the Samaritans, George.’

‘What?’

‘George, you’re live on Rocktalk 99FM. You rang us. A nation awaits your pearls of wisdom.’

‘Well, like, what I wanted to say was, er …’

‘Get on with it, George. I can’t wait much longer. I’m losing the will to live.’

‘Well, you know, it’s about these beggars, like.’

‘What about them?’

‘Well, er, something should be done.’

‘And what precisely do you have in mind?’

‘Dogs.’

‘Dogs, George. I see.’

‘They should set the dogs on them.’

‘What dogs?’

‘Police dogs, I dunno. Any kind of dog.’

‘Alsatians?’

‘Yeah. And Dobermans and Rottweilers.’

‘Yorkshire terriers, miniature poodles?’

‘Are you taking the piss?’

‘Perish the thought, George. It’s just that, well, don’t you think dogs are a bit drastic? How about firehoses?’

‘Firehoses. Yeah, why not? That’s a great idea.’

‘Flamethrowers?’

‘I don’t care, I just want them off the streets and back where they came from. It’s not safe for a little old lady to go out of the house without being mugged or raped by these beggars …’

‘Ah, yes … I was wondering when the little old lady would turn up. She normally makes an appearance whenever anyone runs out of rational argument. Tell me, George, when exactly was the little old lady in question last mugged or raped by a beggar?’

‘I’m not taking anyone pacific, like.’

‘Specific.’

‘What?’

‘Specific. The Pacific is an ocean.’

‘Anyway, it could happen if something isn’t done. These Romanians are a bloody menace. They should be rounded up at gunpoint and sent back to Rome where they belong.’

‘Goodbye, George. Don’t bother ringing us again. It’s coming up to midday. That’s all we’ve got time for today and this week, thank God. Join me again at the same time on Monday for another unbelievable assortment of losers and lunatics live on Rocktalk 99FM. Until then, this is Ricky Sparke, wishing you good morning and good riddance. We are all going to hell in a handcart.’

Ricky removed his headphones and threw them onto the console next to the cough-cut button and a rack containing eight-track cartridges. The red on-air light was extinguished, indicating his microphone was switched off. He put his feet up on the desk, lit a cigarette and leaned backwards.

Where on earth do we find these people? It was the same every day, a telephonic procession of inarticulate imbeciles, radio’s answer to the fish John West reject.

Ricky had one underpaid, overworked producer in charge of everything from the running order to making the tea and working the fax machine. His only back-up was a girl on a work experience scheme who couldn’t operate the phones properly and appeared to be clinically dyslexic.

Rocktalk 99FM was the latest incarnation of a station which had started life eight years earlier as Voice FM. Its founders had won the franchise by persuading the Radio Authority they planned to broadcast a cerebral schedule of original drama, discussion, debate and documentaries dedicated to politics, humanitarian issues and the arts. It was going to sponsor live concerts and forums and gave a solemn and binding guarantee to recruit at least forty per cent of its staff from the ranks of the ethnic minorities.

That was the theory, anyway. The ‘promise of performance’ document managed to impress the assorted worthies who make up the Radio Authority, which regulates the commercial sector, and Voice FM was awarded a ten-year licence.

Six weeks before the station went on air, the founding fathers received an offer they couldn’t refuse from an Australian consortium desperate to break into the British market. They trousered the thick end of £15 million between them and withdrew to spend more time with their mistresses.

When Voice FM was launched, it bore little resemblance to the original pitch. Having spent most of their money actually buying the licence, the Australians had virtually nothing left over to spend on content. Out went original drama, documentaries and live concerts.

There was certainly discussion and debate, if that’s what you call cabbies from Chigwell complaining about cable-laying and bored housewives ringing agony aunts with their mundane grievances and PMT remedies.

As for recruiting from the ethnic minorities, that promise was kept, up to a point. The security officer was Bosnian and the cleaners were all illegal immigrants from Somalia.

Two years on, Voice FM was relaunched as Bulletin FM, a cheap-and-cheerful rolling news station, hampered by the fact that it didn’t actually employ any correspondents, just a roster of failed actors hired to read out agency reports and stories copied out of the newspapers and off the television by kids on work experience.

The traffic reports were delivered by one Ronnie Dugdale, an alcoholic ex-bus driver who had once enjoyed fifteen minutes’ fame as a contestant on Countdown. He was the first player to score nil points, failing to muster any word over four letters and missing the target on the numbers board by more than two hundred. After the show he was escorted from the green room by security for attempting to grope Carol Vorderman, the show’s attractive co-presenter. On the way home he was breathalysed, disqualified from driving for two years and sacked from the bus company. Still, it made him a minor celebrity and minor was all the celebrity Bulletin FM could afford.

When the motoring organizations withdrew co-operation because they hadn’t been paid, Ronnie took to making up his traffic reports, which became increasingly bizarre as the day wore on and he shuttled backwards and forwards between the Bulletin FM studios and the Red Unicorn over the road. One afternoon, he arbitrarily announced the closure of half a dozen main arteries and advised drivers to avoid Westminster and Waterloo Bridges because of a fictitious demonstration and march by 20,000 dwarves, demanding equal rights for the vertically challenged.

Unfortunately, thousands of drivers took him at his word. It caused gridlock in central London on an unprecedented scale. The Strand was still jammed at two o’clock the following morning. He was fortunate charges were not preferred.

That was the end of Ronnie’s radio career. Last heard of he was awaiting trial for driving a minicab through the front of a halal butcher’s shop while several times over the limit and while still serving a suspended sentence for driving while disqualified, without insurance, road tax or a valid MOT certificate.

It was also the end of what passed for Bulletin FM’s credibility. The station’s owners decided that rolling news was not the way ahead and convinced themselves that sport was the next big thing. Having seen the success of Sky, they decided to launch a dedicated football station, Shoot FM. Not actually having the commentary rights to any live football, they were reduced to inviting listeners to call in match reports on their mobiles from the back of the stands. This lasted about six weeks, until the lawsuit landed from the Premier League. Shoot FM struggled on, covering non-league football and commentating on the Spanish Primera Liga, until Sky realized it was being ripped off and the commentator was in fact sitting in Shoot FM’s studio watching the game on Sky Sports Three.

With three years left on the licence, the Aussies played their last card. Scouring the franchise document they discovered it allowed them to play forty per cent music by content. They decided they could always fill the other sixty per cent with phone-ins and thus Rocktalk 99FM, a mixture of classic rock and pig-ignorance, was born.

It coincided with Ricky Sparke, controversial columnist, being shown the door by the ailing Exposer, a downmarket tabloid aimed primarily at the illiterate and famous for being the first Fleet Street publication to feature full-frontal nudity.

The Exposer was Ricky Sparke’s last-chance saloon as far as newspapers were concerned. He’d blown more jobs than Linda Lovelace, largely through drink and an inability to tolerate fools. He was a gifted polemicist but had a history of throwing typewriters through windows if some lowly sub-editor changed so much as a single syllable of his prose.

For once, drink and madness played no part in Ricky’s downfall. His contract had run its course and the editor decided there was no longer any point in paying £100,000 a year to a wordsmith for a once-a-week column, given the fact that few of his readers could actually read.

Ricky was replaced by a former lap-dancer who dispensed sex advice in the form of a comic strip with voice bubbles, True Romance-style. When her first column appeared, readers were invited to take part in a competition to describe in no more than twenty words why they’d like to give her a bikini wax. The winner got to give her a bikini wax. Ricky entered under a false name and came second.

Ricky had frequently appeared on Voice FM, Bulletin FM and Shoot FM as a guest pundit, filling the voids between callers with sarcastic banter and mock outrage. It didn’t pay much but there was always a steady supply of drink in the studio, which Ricky reckoned at least saved him a few bob. He was quite good at it, too.

When Rocktalk 99FM was launched, Ricky received a call from Charlie Lawrence, the programme director, who offered him a job as the mid-morning presenter.

Lawrence was a former salesman who started off selling solar-powered boomerangs to tourists at Circular Quay in Sydney, wound up in newspaper telesales and graduated to promotions manager at an ailing talk-radio station.

He transformed the station, turning it into Down Under AM, Australia’s first all-gay on-air chatline.

Lawrence shipped up in London, headhunted by Rocktalk FM’s Australian management in an act of desperation.

‘We need controversy, we need to provoke people. We need someone who’s not afraid to speak his mind. You’re the man, mate,’ Lawrence had insisted over a bottle of Polluted Bay Chardonnay.

Ricky didn’t take much persuading. He was also available. What Lawrence didn’t know was that Ricky had already been told his contract at the Exposer wasn’t being renewed and that he had nowhere else to go.

Ricky was almost potless. Although he had always been handsomely paid, his prodigious thirst and the mortgage on his flat in a mansion block at the back of Westminster Cathedral swallowed his earnings. He could just about manage to service his credit cards and his extended bar bill at Spider’s.

He could have lived somewhere cheaper, but he needed to be at the centre of town. He also liked being driven, especially since the London Taxi Drivers’ Association had blacklisted him following a column in praise of minicabs. Ricky only discovered this when he clambered into the back of a black cab in Soho one night and asked to be taken home.

The driver looked at Ricky in the mirror and checked. He took a newspaper cutting off his dashboard, held it up to the vanity light, inspected it and turned to get a better look at his dishevelled passenger.

‘You’re him, aren’t you?’

‘Eh?’

‘Sparke. You look older in real life. And fatter. But I can tell it’s you.’ The driver was clutching Ricky’s picture by-line, torn from the pages of the Exposer. It had been taken some years earlier in a professional studio and enhanced by Fleet Street’s finest photographic technology. Although Ricky had worn badly over the years, it was still recognizably him.

‘OK, so it’s me. Give the man a coconut. Now take me to Westminster.’

‘You must be kidding, mate, after what you said about us. You’re barred.’

‘Then take me to the public carriage office. You can’t do this.’

‘I can do what I like. Now get out. Go on. Out!’

Ricky stumbled out of the cab and retraced his steps downstairs into Spider’s. Dillon laughed when Ricky told him the story, gave him another one for the strasse on the house and called a local chauffeur firm to take him home.

When the car turned up, it was being driven by former police sergeant Mickey French, an old mate Ricky had known since the Seventies, when he was a local newspaper reporter and Mickey was PC at Tyburn Row, although he hadn’t seen him for a couple of years. Mickey took him back to his flat, declined an offer of a drink and said he’d call Ricky in the morning. Since that night, Mickey had been Ricky’s regular ride around town.

Not today, though. Mickey had taken the family off for a long weekend at Goblin’s Holiday World and Ricky was left to his own devices. Lunch loomed. Ricky had no wife to go back to. He was married once, to a copytaker on his first newspaper, a printer’s daughter from Lewisham, south-east London.

But it wasn’t going anywhere. Ricky refused to go south of the river and she could never settle north. Since he never came home, it didn’t really matter where they lived. She moved out, filed for divorce after less than a year of marriage and ended up with a used-car dealer in Eltham, three kids, a facelift, a tummy tuck and a villa in Marbella, where three times a year she topped up her fake tan with the real thing.

Ricky never remarried, was never bothered about children, rather liked his bachelor existence. The booze had taken its toll over the years, but had never taken over. Ricky prided himself that he always got up for work, no matter how rough he felt.

‘I’m a milkman. I deliver,’ was his proud boast. And he did deliver. Abuse and insults by the bucketloads, tipped over the heads of the great and the gormless, the rich and fatuous in a succession of newspapers. He’d always been good for circulation but his off-the-ball antics cost him a string of jobs, right back to the time when still in his teens he clattered the long-serving chief reporter of the long since defunct Tyburn Times, sending him tumbling downstairs, in a heated dispute over punctuation, and caused his first employer to tear up his indentures.

A quarter of a century later, he had mellowed, rather like a top-class single malt. Probably because of single malt. His fighting days were over, ever since he had mistakenly stripped to the waist on the Central Line and offered violence to half a dozen Millwall fans making a nuisance of themselves on the way to Loftus Road. He spent three weeks in hospital as a result of that piece of foolhardiness. It cost him three teeth, replaced with some expensive bridgework. Ricky had been knocking off a divorced dental hygienist at the time and had been able to negotiate a discount for cash from the South African dentist with whom she shared a surgery. She eventually gave up on Ricky, hooked up with the dentist and moved to Jo’burg, where she was killed in a drive-by shooting. Some people never know when they’re well off, Ricky remarked when he heard the news.

‘How’s it going, mate?’

Ricky looked up and saw Charlie Lawrence standing in the studio doorframe.

‘This isn’t a job for grown-ups,’ he replied, running his fingers roughly through his hair, massaging his scalp as he did it, trying to relieve the tensions of dealing with the great unwashed and their uninformed, unfocused view of the world, three hours a day, five days a week.

‘You look plenty grown up to me, mate. A little too grown. Not so much grown up as grown out. You should take up squash,’ said Charlie, indicating Ricky’s middle-age spread.

‘You must be joking,’ Ricky said. ‘Anyway, this is all bought and paid for. Once you’re older than your waist size, it’s not worth the bother.’

‘Oh, no? Take me, mate. We’re, what, about the same age? I’ve still got a six-pack.’

‘So have I. It’s in my fridge and it’s full of Guinness.’

‘You should take more exercise. It’ll do your temper good, too.’

‘There nothing wrong with my fucking temper.’

‘That’s not what it sounded like to me this morning.’

‘What are you going on about, Charlie?’

‘I thought we were a little bit on the grumpy side today.’

‘We? You mean me. Well, it’s all right for you sitting in your strategy meetings. I’m the one who has to handle all these fuckwits. Who needs them?’

‘That’s where you’re wrong, mate. They may be fuckwits, but they’re our fuckwits. And we’ve got fewer of them by the week. Who needs them? We need them. The advertisers need them. You need them, mate. You definitely need them.’

‘And what’s that supposed to mean?’ snapped Ricky, swivelling on his chair, his right arm colliding with his Rocktalk 99FM mug, sending stale, cold coffee cascading over the console.

‘Can we have a word?’

‘That’s what we are doing, isn’t it?’

‘I mean an official word. In my office.’

‘This is my office. Say what you’ve got to say.’

‘I’ve just got these, mate. Take a look.’ Charlie threw a stack of ring-bound A4 paper on the console. Ricky picked it up and studied it. Numbers, figures, graphs.

‘What is this?’

‘The RAJARs, mate. The official listening figures for the last quarter. We have been experiencing some very serious churn.’

‘Since when have you been running a dairy?’

‘You’re the one who’s always boasting about being a milkman. I’m afraid you’re not delivering.’

‘I’m here every day. I’ve never let you down.’

‘We’re not talking attendance here. You don’t get a silver star for turning up. This is what matters,’ said Charlie, pointing to the bottom line on the second sheet of paper.

‘And what does it say?’

‘It says that between nine and noon we are down almost thirty per cent. And who’s on between nine and noon?’

‘That’s only to be expected. I’m new to the station. People have got to get used to me. You have to figure that it will take time to win people round. Three months ago, before I started, this was a football station, with no fucking football. I’ve had to start from scratch.’

‘You can’t argue with a fall of thirty per cent.’

‘I can. Three months ago, the only listeners you had were a bunch of soccer-mad morons too stupid to find Radio Five.’

‘That’s as maybe, but there were thirty per cent more of them.’

‘Of course, that stands to reason. The kind of terrace plankton you had listening to you then are hardly going to stay tuned for adult-orientated rock interspersed by saloon-bar pontificating.’

‘I know that. But if you look at the figures more closely, you’ll find that the new audience is falling away, too. It’s down ten per cent over the past two weeks, according to our tracking.’

‘You picked the format. And you picked the presenter. Me.’

‘True. But I didn’t know you were going to go out of your way to piss off the listeners.’

‘I don’t.’

‘You do, mate.’

‘Don’t.’

‘What about George just now?’

‘The man was a fucking idiot. Turn the dogs loose on beggars? For fuck’s sake.’

‘A lot of people out there agree with him.’

‘A lot of people want to bring back hanging, drawing and quartering.’

‘Look, Ricky, all I’m saying is lighten up. Cut them some slack. Don’t be so short with them.’

‘Short is what I do.’

‘So you’ve got to do something a bit different. Look on the audience as our customers. Be nice to them once in a while. Play to their prejudices. Don’t sign off by dismissing them as a bunch of losers and lunatics. God knows what message that sends to the advertisers.’

Ricky got up and pulled on his coat from the back of his chair. He picked up his bag and headed for the door. Charlie didn’t move.

‘Excuse me, Charlie. I don’t need this after a long week. I’m off to get pissed.’

Charlie’s eyes hardened. His corporate smile faded.

‘I don’t think you’ve been listening to me, Ricky.’

‘Sure I have.’

‘Oh, I don’t think so.’

‘So what’s your point?’

‘My point is that this station, particularly in this time slot, is going down the dunny. I’m paying you a lot of money. Too much money. I’d never have given you so much if I’d known you’d already been kicked out of the Exposer.’

‘I wasn’t kicked out. I just, er, left.’

‘Don’t lie to me. They didn’t renew your contract. And they replaced you with the Picture Book lady. I should have fucking hired her myself.’

‘And what, exactly, is that supposed to mean?’

‘It means that if these figures don’t show a serious upturn, you’re finished.’

‘See if I care.’

‘Oh, but you do care, Ricky. This is the last train to Clarksville for you, mate. There’s not a newspaper left in London would hire you and if you screw up this gig, there’s not another radio station would touch you either. Just you think on that when you’re diving headfirst into the European wine lake in ten minutes’ time. Think damned hard. Think about your bar bills and your monster mortgage on your funky little bachelor pad. You’ve got to raise your game. If we’re not up at least thirty per cent, back to where we were, by the next survey, you’re dead meat. You’ve got three months.’