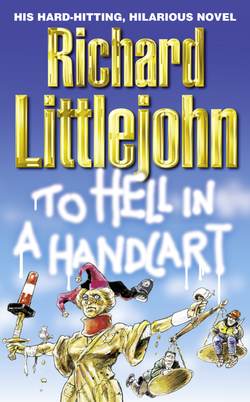

Читать книгу To Hell in a Handcart - Richard Littlejohn - Страница 7

One

ОглавлениеThe Tigani, Romania

The Tigani doesn’t feature on many maps. It isn’t sign–posted. The Tigani doesn’t advertise. Strangers are rare in these parts.

The Tigani – Gypsyland. Bandit country, home to six hundred close-knit families.

The police never ventured here. There had been no official law enforcement since the fall of Communism and the death of the dictator Ceausüescu. When the men in the black Mercedes S500 had stopped en route to ask directions, the non-gypsy locals questioned their sanity.

Their $100,000 limousine passed silently along the dust road, its computer-assisted air suspension soaking up the potholes like a sponge absorbing spilt milk. The trademark double-glazed smoked glass of the Daimler-Benz company concealed the faces of the driver and his three passengers.

It had cost the men in the Merc $100 and a carton of Marlboro to persuade a taxi driver from a town thirty miles away to lead them to the turning for Gypsyland. They followed his rotting Romanian-built Renault saloon for over an hour before he pulled off the single carriageway, pointed them towards their destination and wished them good luck. Then he was off in the opposite direction in a cloud of dust.

It had taken them just over three hours to cover the ninety miles from the Romanian capital of Bucharest, the final leg of a journey begun in Moscow.

As the car made its stately progress along the unmetalled lane, it was surrounded by raggedy, bare-footed, snot-nosed children and their semi-feral pets. Further back stood a gaggle of women aged from fifteen to seventy-five, wearing traditional Romanian peasant costume, long skirts, woollen jackets and headscarves. The younger women clutched babies in swaddling clothes.

They passed a group of men, all dressed in the familiar Eastern European uniform of denims, sweatshirts bearing the names and logos of provincial English football clubs, trainers on their feet. They pulled on untipped cigarettes and watched, warily.

Behind them loomed a derelict cement factory, which had closed eleven years earlier, a monument to the futility of central planning. There was real poverty here. Families of seven and eight sharing two rooms, with bare floors and a few sticks of furniture, heated inadequately by a simple log fire.

Yet at one end of the village stood a few new houses, red and white brick-built, with one or two cars in the driveway. These were home to the Popescu clan, the town’s ruling Roma gypsy family.

The Mercedes approached the biggest house in the street, a neat two-storey construction, with uPVC windows, a bright red front door and a paved driveway, upon which stood a Toyota pickup truck, with heavy-duty towing attachment, and an old-model BMW 525i. There were flowers in the garden, in stark contrast to the barren patches of yard elsewhere in the town.

This was the home of Marin Popescu, leader of the Roma clan, the self-styled Bullybasa, whose word was what passed for law in the Tigani.

The driver pulled into the paved driveway and brought the Mercedes to a halt behind the BMW. He popped the central locking.

Three men in Armani suits and Gucci loafers got out. They were all wearing immaculate black, collar-less shirts and sunglasses. The humidity stuck to them like warm glue, in stark contrast to the filtered, constant sixty-eight-degree, humidified air in the Mercedes. A small crowd of peasants watched from a distance as two of the three Russians approached the front door. There was no movement from within the house.

The biggest of the group pulled the wrought-iron handle of a bell hooked up to the door and waited for a reply.

He stepped back and surveyed the front aspect. Not a curtain twitched.

‘Marin Popescu,’ he called.

Nothing.

The smallest of the three men returned to the car and rapped his knuckles on the driver’s window. The boot lid eased open with a gentle clunk. He walked to the back of the car, bent over the boot, reached inside, removed a tarpaulin and retrieved a Soviet Army-issue, hand-held, anti-tank grenade launcher.

‘Marin Popescu,’ the big man called out again.

Silence.

The big man and his other companion strolled around to the back of the Mercedes. The small man moved to one side and took up position on one knee about thirty feet from the front door.

The crowd withdrew and scattered for cover. The other two men climbed back in the Mercedes and the driver reversed slowly.

The small man squeezed the trigger, propelling an armour-piercing grenade in the direction of the front door. It hit the target, shattering the reinforced steel behind the wooden façade, passing along the hall and exiting via a kitchen window. It slammed into a tractor parked at the rear and exploded, igniting the tractor’s fuel tank, sending it thirty feet into the air in a spectacular, incandescent fireball, shattering every window at the back of the house, melting the uPVC frames like putty.

The small man put the grenade launcher back in the boot of the Mercedes and replaced the protective tarpaulin, like a mother covering her precious, newborn baby.

The other two men got out of the car, clutching Kalashnikovs. The small Russian took a machine pistol from a holster under his left armpit. They waited for the smoke to clear, then walked towards the house.

As the smoke parted, they could see the figure of a man, 5ft 9ins, medium build, greasy, greying hair, walking towards them, his arms outstretched towards the heavens.

The Bullybasa was a less impressive figure than they had expected, even though he was immaculately dressed in designer trousers and silk shirt, with an expensive watch on the wrist of his extended left arm.

He was in his late forties, with a weathered complexion, typical of the Roma people. His nervous smile revealed a gold front tooth.

He had already been humiliated in front of the town. Even if he came out of this alive, he might never be able again to command fear and respect in the Tigani. It was time to negotiate.

‘Gentlemen. I am Marin Popescu,’ he said in the pidgin Russian he had picked up as a result of his involvement in the car-smuggling racket. ‘No more, please. Not in front of my people. Follow me into the house. We can resolve this. Come.’

He backed into the smouldering hallway, past the remnants of some expensively embroidered wall hangings.

Marin Popescu led his three visitors from Moscow into a large sitting room, furnished with plush Persian rugs, upholstered leather and mahogany sofas and matching footstools. A 46-inch back-projection Sony home cinema TV stood in one corner, its cable leading outside to a large satellite dish, like a giant wok, now containing one molten tractor.

The big man spoke.

‘Where is he?’

‘Gentlemen, we should talk.’

‘We have nothing to discuss.’

‘Where is he? Where is your son, Ilie?’

‘I am not able to tell you that. I do not know.’

The big man levelled the muzzle of his Kalashnikov at Marin’s head.

‘No, please,’ Marin pleaded.

The big man swivelled left and unloaded ten rounds into a wall hanging hunting scene above the fireplace.

‘For the last time. Where is he?’

‘He is not here.’

‘We know that.’

‘He has not been here.’

The big man raised the Kalashnikov and smashed Marin round the temple. The Bullybasa collapsed in a heap on the marble tiled floor.

‘OK,’ he said. ‘Enough. He has been here. He was here three weeks ago. But he is not here now. He is very afraid. He has run. He has gone. But he told me to say you will get your money. He is very sorry, it was not his fault.’

‘Where is he?’

‘He has gone to England, to get your money.’

‘Where in England?’

‘London, maybe. I’m not sure. But he will be back with your money. He will steal cars, ship them to me. I will sell them, give money to you.’

‘Not good enough.’

The big man put the Kalashnikov to Marin’s head. He pressed his Gucci loafer into his throat.

The second Russian reached into the pocket of his Armani linen suit, took out a chamois leather pouch and removed a pair of silver-plated pliers.

‘You know what they say about Russian dentistry?’ The big man smiled for the first time. ‘It’s all true.’

As he pressed his foot into Marin’s Adam’s apple, the second Russian knelt beside him and squeezed the Bullybasa’s streaming nostrils. Marin gasped for breath.

The second Russian clamped the pliers onto Marin’s golden front tooth and yanked. Marin let out an agonized, terrified screech and his tooth was wrenched from its roots, ripping his gum and top lip in the process. He writhed in agony on the floor as the big man released his grip. His mouth was a claret gash. The blood poured through his fingers. The pain was excruciating.

‘We’ll call that a down payment,’ said the big man.

Marin cried out in pain, like a wounded fox caught in a snare.

‘London?’ mused the big man, wiping his forehead with a silk handkerchief.

‘He will get your money,’ Marin tried to reassure the Russian, even though he was gagging on his own blood.

‘Money?’ laughed the big man. ‘It’s gone beyond money.’

He lowered the Kalashnikov and pumped two bullets into Marin’s skull, one in each eye, putting the Bullybasa out of his misery.

The three Russians walked out of the house and settled back into the Mercedes.

The driver reversed, engaged Drive and motored slowly out of town. There was no reason to hurry. The Bullybasa was dead. The car was bulletproof. And the police never come within twenty-five miles of the Tigani.

As they drew onto the road to Bucharest, the big man picked a satellite phone from the centre console and punched in a number.

Seconds later, a voice in Moscow answered.

‘Sacha, it’s me,’ said the big man. ‘Who do we know in London?’