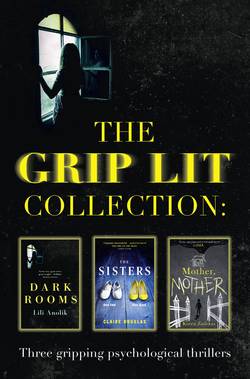

Читать книгу The Grip Lit Collection: The Sisters, Mother, Mother and Dark Rooms - Koren Zailckas, Claire Douglas - Страница 12

Chapter One

ОглавлениеI see her everywhere.

She’s in the window of the Italian restaurant on the corner of my street. She has a glass of wine in her hand, something sparkly like Prosecco, and her head is thrown back in laughter, her blonde bob cupping her heart-shaped face, her emerald eyes crinkling.

She’s trying to cross the road, chewing her bottom lip in concentration as she waits patiently for a pause in the traffic, her trusty brown satchel swinging from the crook of her arm.

She’s running for a bus in black sandals and skinny jeans, wire-framed glasses pushed back on to bedhead hair.

And each time I see her I begin to rush towards her, arm automatically rising to attract her attention. Because in that fraction of a second I forget everything. In that small sliver of time she’s still alive. And then the memory washes over me in a tsunami of emotion so I’m engulfed by it. The realization that it’s not her, that it can never be her.

Lucy is everywhere and she is nowhere. That’s the reality of it.

I will never see her again.

Today, a bustling Friday early evening, she’s standing outside Bath Spa train station handing out flyers.

I catch sight of her as I’m sipping my cappuccino in the café opposite, and even through the rain-spattered window the resemblance to Lucy makes me do a double take. The same petite frame swamped in a scarlet raincoat, pale shoulder-length hair and the too-large mouth that always gave the impression of jollity even when she was anything but happy. She’s holding a spotty umbrella to protect herself from another impromptu spring shower and her smile never fades, not even when she’s ignored by busy shoppers and hostile commuters, or when a passing bendy-bus sends a mini tidal wave in her direction, splashing her bare legs and her dainty leopard-print pumps.

My stomach tightens when a phalanx of businessmen in suits obscure my view for a few long seconds before they move, as one entity, into the train station. The relief is palpable when I see she hasn’t been washed away by the throng but is still standing in the exact same spot, proffering her leaflets to disinterested passers-by. She’s rummaging in an oversized velvet bag while trying to balance the handle of her umbrella in the nook of her arm and I can tell by the hint of weariness behind her cheery smile that it won’t be long before she calls it a day.

I can’t let her go. Gulping back the rest of my coffee and burning the roof of my mouth in the process, I’m out the door and into the rain while shouldering on my parka. I zip it up hurriedly, pull the hood over my hair to guard against the inevitable frizziness and cross the road. As I edge closer I can see there is only a slight resemblance to my sister. This woman’s hair is more auburn than blonde, her eyes a clear Acacia honey, her nose a small upturned ski-slope with a smattering of freckles. And she looks older too, maybe early thirties. But she’s as beautiful as Lucy.

‘Hello,’ she smiles, and I realize I’m standing right next to her and that I’m staring. But she doesn’t look perturbed. She must be used to people gawping at her. If anything, she looks relieved that someone has bothered to stop.

‘Hi,’ I manage as she hands me the leaflet, limp from the rain. I accept it and my eyes scan it quickly. I take in the bright print, the words ‘Bear Flat Artists’ and ‘Open Studio’ and raise my eyes at her questioningly.

‘I’m an artist,’ she explains. By the two red spots that appear at the apples of her cheeks I can tell she’s new to this, that she’s not qualified yet to be calling herself an artist and that she’s probably a mature student. She tells me she has a studio in her house and she’s opening it up to the public as part of the Bear Flat Artists weekend. ‘I make and sell jewellery, but there will be others showing their paintings, or photographs. If you’re interested in coming along then you’re most welcome.’

Now that I’m closer to her I can see she is wearing two different types of coloured earrings in her ears and I wonder if she’s done it on purpose, or if she absent-mindedly put them on this morning without noticing that they don’t match. I admire that about her, Lucy would have too. Lucy was the type of person who didn’t care if her lipstick was a different shade from her top or her bag matched her shoes. If she saw something she liked she wore it regardless.

She notices me assessing her earlobes. ‘I made them myself,’ she says, fingering the left one, the yellow one, delicate and daisy-shaped, self-consciously. ‘I’m Beatrice, by the way.’

‘I’m Abi. Abi Cavendish.’ I wait for a reaction. It’s almost imperceptible but I’m sure I see a flash of recognition in her eyes at the mention of my name, which I know isn’t down to reading my by-line. Then I tell myself I’m being paranoid; it’s still something I’m working on with my psychologist, Janice. Even if Beatrice had read the newspaper reports or watched any of the news coverage about Lucy at the time, she wouldn’t necessarily remember, it was nearly eighteen months ago. Another story, another girl. I should know, I used to write about such things on a daily basis. Now I’m on the other side. I am the news.

Beatrice smiles and I try to push thoughts of my sister from my mind as I turn the leaflet over, pretending to consider such an event while the rain hammers on to Beatrice’s umbrella and on to the back of my coat with a rhythmic thud thud.

‘Sorry it’s so soggy. Not a good idea to be dishing out flyers in the rain, is it?’ She doesn’t wait for me to answer. ‘You don’t have to buy anything, you can come along and browse, bring some friends.’ Her voice is silky, as sunny as her smile. She has a hint of an accent that I can’t quite place. Somewhere up north, maybe Scottish. I’ve never been very good at placing accents.

‘I’m fairly new to Bath so I don’t know many people.’ The words pop out of my mouth before I’ve even considered saying them.

‘Well, now you know me,’ she says kindly. ‘Come along, I can introduce you to some new people. They’re an interesting bunch.’

She leans closer to me in a conspiratorial whisper, ‘And if nothing else it’s a great way to have a nose at other people’s houses.’ She laughs.

Her laugh is high and tinkly. It’s exactly like Lucy’s and I’m sold.

As I meander back through the cobbled side streets I can’t stop my lips curling up at the memory of her smile, her warmth. I already know I’ll be stopping by her house tomorrow.

It doesn’t take me long to reach my one-bedroom flat. It’s in a handsome Georgian building in a cramped side road off the Circus that’s lined with cars parked bumper to bumper. I let myself into the shabby hallway with its grey threadbare carpet and salmon-pink woodchip walls, pausing to peel a brown envelope from the sole of one of my Converse trainers. I look down to see several letters scattered in the hallway and pick them up hopefully when I see they’re addressed to me. They have muddy footprints decorating the front where my neighbours have trodden over them to get to their flat without bothering to pick them up. I flick through them and my heart sinks a little; all bills. Nobody writes letters any more and certainly not to me. Upstairs, in a box on top of my wardrobe I have a stash of letters, notes, museum stubs and other ephemera that was Lucy’s. Rescued from her room after she died. We both kept all our correspondence from over a decade ago when we were at different universities, before we could afford computers and laptops, before we even knew how to email.

I push past the mountain bikes that belong to the sporty couple who live in the basement flat, cursing as my ankle scrapes on one of the pedals, and climb the stairs to the top floor. I’m still clutching the leaflet which has started to disintegrate from the rain.

I unlock my front door and step into the hallway, which is much smarter than the cluttered communal entrance downstairs. I’m only renting it but the landlord decorated the walls a pale French grey and installed an antique oak effect wooden floor before I moved in. Then Mum promptly turned up and swiftly dressed the place with rugs, throws and framed photographs to make the flat look more ‘homely’, to give the only child she has left a reason to live.

As I hang up my wet coat my heart sinks when I notice my mobile phone on the black veneered sideboard. I pick it up with dread, hoping that I don’t have any missed calls, but there are ten. Ten. I scroll through the list. Most are from Mum but a couple are from Nia too, along with messages asking me to give them a call, their voices laced with barely disguised panic. I’ve only been gone two hours but I know they think I’ve tried to do away with myself. It’s been nearly a year since I ended up in that place – I still can’t bear to think of it – but they still believe I’m unstable, psychologically weak, that I shouldn’t be left on my own for too long. I pull the sleeves of my jumper over my wrists, subconsciously hiding the silvery scars that will never fade.

The flat is steeped in dark shadows although it’s only a little after five. Outside it looks as if a giant dirty grey sheet has been thrown over Bath. I switch a lamp on in the living room, instantly warmed by the bright orange glow, and sink on to the sofa, putting off ringing my parents. I’ll have to do it soon otherwise Dad will speed over here in his acid-green Mazda on the pretence that he’s ‘just passing’ when he actually wants to check that I’m not lying unconscious on my bed surrounded by empty bottles of pills.

My mobile punctuates my thoughts with a tinny rendition of ‘Waterloo Sunset’ by The Kinks and I drop it in shock and watch, bewildered, as it body-pops across the floor. Panic rises. I didn’t catch the name flashing up on my phone. I don’t know who’s calling me. My heart starts to race and I feel the familiar clammy palms, the churning in my stomach, my throat constricting. Calm down, remember your breathing exercises. It must be someone you know. That song means something to you. ‘Waterloo Sunset’. London. Nia. Of course.

I almost want to laugh in relief. It’s Nia calling. Only Nia. My heart slows and I bend over to pick up my phone. By now the music has stopped and Nia’s name flashes up under missed calls.

‘For Christ’s sake, Abi, you had me worried. I’ve been trying to get hold of you for hours,’ she snaps when I call her back.

‘I’ve only been gone for two and I forgot my phone.’

‘What have you been doing?’ I detect the thread of doubt in her voice, as though she suspects I’ve been preparing to hang myself in the woods or stick my head in the gas oven. ‘Have you got no work on?’

I suppress a sigh. Work used to be commissioning editor on a glossy magazine. Now it’s the odd bit of freelance when I’m up to it, or usually when I’m running low on cash. I know if I’m not careful I’ll lose all my contacts. I’ve only got a handful of loyal ones left, which isn’t surprising after everything that’s happened over the last year or so.

‘Miranda says there isn’t much work around at the moment,’ I lie. Miranda, my old boss, is one of the loyal ones. I toss the leaflet I’m still holding in the direction of the coffee table; it misses and, weighed down by the rain, sinks to the floor. It’s unreadable now, turned into papier-mâché, but I’ve made a photocopy of it with my retina. I kick off my trainers then put my feet up on to the velvety cushions and stare out of the sash window over the rooftops of Bath, trying to pick out the spire of the Abbey among the mellow brick. The rain abruptly halts and the sun struggles to reveal itself from behind a black cloud.

Her voice softens. ‘Are you okay, Abs? You’re living by yourself now in a place you barely know and …’

‘Mum and Dad live four miles away.’ I force a laugh but the irony isn’t lost on me. I’d been desperate at eighteen to go to university to escape my parents and the small town of Farnham in Surrey where we lived. And now look at me. Nearly thirty years of age and I’ve followed them, like a stalker, to this new city where they’ve come in a bid to try and rebuild their fractured lives. Not much chance of that with me hanging around, reminding them of what they’ve lost.

I can’t bring myself to tell Nia about Beatrice. Not yet. Not after last time. She’ll only worry.

‘I’m honestly fine, Nia. I was walking around Bath and then it began to rain so I went for a coffee. Don’t worry about me. I love it here. Bath’s peaceful.’ Unlike my mind, I add silently.

‘Peaceful?’ she scoffs. ‘I thought it was full of tourists.’

‘Only in the summer. I mean, it’s busy, but not as frenetic as London.’

She falls silent and there it is. All that’s unspoken between us, wrapped up in one word. London. I know she’s thinking about it. How can she not? It’s all I think about when I speak to her. That cramped Victorian terrace that the three of us shared. That last night. Lucy’s final hours.

‘I miss you.’ Her voice sounds small, comfortingly familiar with its soft Welsh lilt. For a second I close my eyes and imagine how my life used to be; the hustle and bustle of London, the job that I had loved, the array of glittering parties and glamorous events thanks to Nia working in fashion PR, Lucy and Luke, Callum …

But looking back before that night is as if I’m looking back at someone else’s life, it’s so different to the one I lead now.

‘I miss you too,’ I squeak, then I force myself to make my voice sound cheerful. ‘How is it, living in Muswell Hill? Anything like Balham?’

‘Different, and yet the same. You know what I mean,’ she sighs. I know exactly what she means. ‘Abs, I’ve got to tell you something. I’ve been worrying about it for ages. I’m still not sure if you should know.’

‘Okay …’ I feel a sense of unease.

‘It’s Callum. He’s been in touch.’

I wait for the panic to descend upon me. But nothing, apart from a slight fluttery sensation behind my belly button. Is that what the antidepressants have done to me? Dulled the sensations, the memory of him? I try to conjure up an image of his six-foot-two-inch frame, his almost-black hair, his heavily lashed blue eyes, those tight jeans and leather jacket. I loved him, I remind myself. But he too is wrapped up in the memories of that night. He’s been sullied for ever, as has everything else.

‘What did he want?’ I’m trying to sound nonchalant but I know Nia won’t be fooled. She’s my best friend and she was there, she knows how much he meant to me.

‘He asked me for your number. He wants to talk.’

‘Shit, Nia,’ I gasp, taking ragged breaths. ‘Did you give it to him? Does he know where I live? If he knows, he’ll tell Luke. You promised me that you wouldn’t tell them where I’ve moved to. You promised.’ My voice is rising as I think of Luke’s face the last time I saw him, frozen in grief as he told me calmly that he would never forgive me for Lucy’s death. His words, along with his detachment, were as painful as the blade I took to my wrists.

‘Abi, calm down,’ she urges. ‘I haven’t told him anything. I don’t even think Callum lives with Luke any more.’

‘I’m sorry,’ I gulp, making an effort to suppress my anxiety, my fear. ‘I can’t speak to him. I can’t. Ever again …’

‘It’s okay, Abi. Don’t worry. I haven’t told him anything about you. I have his number, if you ever decide that you’re ready to speak to him …’ she trails off.

I stay silent, knowing I’ll never be ready. Because to speak to him would mean revisiting the night I killed my sister.