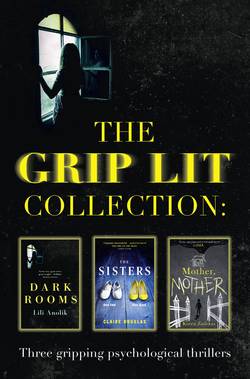

Читать книгу The Grip Lit Collection: The Sisters, Mother, Mother and Dark Rooms - Koren Zailckas, Claire Douglas - Страница 17

Chapter Four

ОглавлениеReturning to my cold, empty flat after the warmth, noise and babble of Beatrice’s vibrant house makes me feel like a dog that’s been banished from its family home to a kennel in the garden.

The silence bears down on me oppressively, reminding me that I do live on my own, that there is no Nia clattering around the kitchen making endless cups of tea, or Lucy curled up on the sofa tapping away at her laptop. Even though they’ve never lived with me here, in this flat, I still can’t get used to being without them, still expect to see the ghosts of them around every corner. It’s one of the reasons I left London.

I switch on the lamp and when I cross the living room to close the curtains I catch sight of something, someone, on the street below. My heart quickens. A man is standing by the front gate, I can barely make out his silhouette against the inky night. He has his collar turned up, a cigarette hanging moodily from his lips; the detail of his face is unclear, shadowy, a pencil drawing where his features have been rubbed out, but the shape of his head, the lanky figure, is so familiar I instantly know it’s Luke. It’s Luke and he’s found me. I fumble for my mobile that’s in the pocket of the jacket I’m still wearing, desperately scrolling for my parents’ number with trembling fingers. Then he looks up at my window, his eyes briefly meeting mine and I freeze. I watch, my mobile still in my hand, as he flicks his cigarette to the kerb and saunters down our garden path to ring the bell of the flat below. It’s not Luke, of course it’s not Luke. Nia would never break her promise to me. But it’s an unpleasant reminder that I’m not the only one who can’t forgive myself for what happened that Halloween night over eighteen months ago.

I sprint around the flat in a sudden frenzy of drawing curtains and switching on lights. When my heart finally slows and my breathing returns to normal I settle on the sofa with a cup of coffee and call Mum. I need to hear a comforting voice after the fright I’ve had.

She sounds husky, as if I’ve awoken her from sleep and I realize it is past midnight. ‘Abi? Are you okay?’ I imagine her sitting up in bed in her flannel pyjamas, her heart racing, expecting to hear me in tears, so I quickly explain that nothing is wrong. And then, without thinking, I tell her about Beatrice. I mentally slap myself when I hear the apprehension in her voice as she answers, ‘This isn’t the same as before is it, love?’

‘Of course it’s not,’ I snap, my cheeks burning when I think about Alicia.

She hesitates and I can tell that there is a lot more she wants to say, but my mother has always been a great believer in thinking before speaking. Instead she says how wonderful it is that I’ve found a friend, that I’m beginning to settle in Bath. Then she reminds me, as she always does, that I need to keep seeing Janice, that I mustn’t forget to take my antidepressants, that I have to do all I can to make sure I don’t end up in that place again – she lowers her voice when she says this last bit, in case the neighbours can hear through the walls that her daughter has been in a mental institution.

When she eventually rings off I sit with the phone in my lap. I’m consumed with an urgency I’ve not felt for a long time when I think of tonight, of Beatrice. The dancing in her living room after all her potential ‘clients’ had gone home, her cool, arty friends, the wine we drank so we were floppy and silly and finding everything hilarious, and then afterwards when the lights went down and we all slumped on to Beatrice’s velvet sofa, me squashed in between her and Ben so that each of my thighs touched one of theirs; believing for the first time in ages, that I belonged.

I touch the necklace at my throat, the necklace that Beatrice has made with her own two hands. She’s the one, surely? Even our names merge with each other – Abi and Bea – Abea. Does she sense it too? This connection, this certainty that we are supposed to meet?

Then the darkness washes over me, dousing my joy. I don’t deserve to be happy. Guilt. Such a pointless emotion, Janice constantly tells me that, yet I am consumed by it tonight. You were found not guilty, Abi. I can almost hear Lucy’s soft voice, her breath against my ear, as if she’s curled up on the sofa next to me, and then to my surprise, my own, deeper voice, coming out of nowhere, bounding off the walls of my tiny flat so that it startles me: ‘I’m so sorry, Luce. I’m so sorry. Please forgive me.’

Two days pass without a word from her. Two days holed up in my flat with the rain drumming on the skylights in the roof, the fluke hot weather of Saturday a distant dream. Mum rings and invites me over, but I decline, telling her I’ve got some work to catch up on, when in reality the thought of spending the bank holiday with my parents but without Lucy makes the grief bubble back up to a dangerous level. Our family resembles a table with a leg missing; incomplete, forever ruined.

I know it’s not healthy for me to be on my own for too long, it gives me more time to obsess, to think about Lucy, to remember her last night; the panic, the fear. It comes back to me in moments when I least expect it, when I’m lying in bed on the edge of sleep, or when I’m perusing Lucy’s page on Facebook, re-reading the condolences from her three hundred-plus Facebook friends. I can suddenly smell the wet grass mixed with the smoke from the engine, see the blood caked on Lucy’s head, her beautiful but eerily still face as Luke cradles her in his arms, hear Callum shouting desperately into a mobile phone for an ambulance, feel the touch of Nia’s comforting hand on my shoulder as I crouch by the tree, the bark rough against my back, the metallic taste of blood on my lips and bile in the back of my throat as she whispers over and over again that Lucy’s going to be okay, in a futile attempt to reassure me, or herself. And the rain, so much rain, coming down in sheets so that our clothes clung to our bodies; coming down like tears.

To vanquish the relentless, soul-destroying thoughts, I try to remember Beatrice’s soft Scottish accent, the hurried excitable way she talks, her warmth, her humour. I’m still unsure if she knows about what I’ve done – a quick Google search would reveal everything. Is that the reason she hasn’t got in touch? Who wants to be friends with someone who’s killed her own twin sister?

I have a connection with Beatrice, even more than I first thought. Not only is she a twin too, she’s lost someone close to her, she understands me. Now that I’ve found her I know that I can’t let her go.

It’s still raining when I turn up at her door clutching an umbrella and cradling a bunch of large white daisies. I pull the bell and wait, jumping back off the stone step in alarm when a brown spider with yellow flecks drops in front of my face then desperately clambers its way back up its own silvery thread to the fanlight above.

There’s no answer so I wait a few more seconds before stepping forward to pull the bell again. When nobody comes to the door, I lean over the iron railings and peer into the ground-floor window where, apart from an easel and a couple of bookshelves crammed with irregular-sized, glossy hardbacks, it’s empty. I’m about to reluctantly leave when my eye catches a flash of something at the window of the basement, what I remember as being the kitchen. It’s fleeting, a blur of hair and clothes, but it makes me uneasy and the familiar paranoia creeps over me, causing sweat to pool in my armpits. I know with a certainty that I didn’t feel this morning that I’m not wanted. Am I making a nuisance of myself, as I did once before with Alicia? The feelings I’d thought I’d long since buried of that time – before I was sectioned, when I thought in my grief-addled mind that Alicia was some kind of soul mate – resurface, making me nauseous. Could I have got Beatrice so very wrong like I did with her?

Before Lucy died, I was fun, hard-working, popular within my group of friends. Now look at me. I’ve become the sort of person that others try to avoid, to hide from. My eyes sting with humiliated tears, blurring my vision as I stumble back down the tiled pathway towards the bus stop, the daisies wilting in my arms.

The voice is almost lost in the wind but I can just make out someone calling my name. I turn and there she is, standing in her doorway in her bare feet, toenails bruised with black nail varnish, wearing a blue spotty vintage tea-dress underneath a chunky cardigan, waving frantically at me and smiling. Relief surges through me and all the old doubts crawl back into the recesses of my mind where they belong as I trot towards her.

‘I’m sorry,’ she says as I get nearer. ‘I was on the phone, talking to a client, oh I’m so thrilled to be saying that. I’ve actually got a client. I wasn’t going to answer the door until I saw it was you. Come in, come in.’ She’s talking in her usual fast, excited manner and I can’t stop grinning.

I cross the threshold into the hallway, breathing in the familiar Parma violet smell I already love so much and handing her the now crumpled-looking daisies. Confusion alters her features for a moment so she appears older, sharper. ‘Are they for me?’ she frowns. When I nod self-consciously, explaining that they’re a thank you for the necklace, she takes them from me and smiles shyly, her face softening again. ‘Thanks, Abi. But you didn’t have to. I wanted to give you the necklace. You did me a huge favour on Saturday. Do you want a cup of tea?’

I tell her that I’d love one. Dumping my wet umbrella on the doormat, I nudge off my trainers, relieved that I remembered to put matching socks on this morning, and follow Beatrice through the hallway, the flagstones warm under my feet – of course, she would have underfloor heating – and down the stairs to the basement kitchen. ‘I love your house,’ I say as I admire, yet again, the high ceilings and intricate coving, the Bath stone floors and Farrow and Ball painted walls. Considering it’s full of young people, the house is surprisingly tidy.

By now we’ve reached the kitchen and I shrug off my wet coat and hang it on the back of the chair to dry before taking a seat at the wooden table and it’s as though I’ve come home. A fluffy ginger cat with a squashed face is curled up asleep on the antique-looking armchair in the corner. Beatrice follows my gaze and informs me the cat, a Persian called Sebby, is hers. Lucy loved cats too.

‘He’s getting old now,’ she says fondly. ‘He mainly likes to snooze.’

The house is quieter than it was on Saturday, with the dripping of rain on an outside drain the only sound to be heard, and I hope that it’s only the two of us here. I didn’t notice the little white Fiat with its red-and-green stripe parked outside. Ben told me the other night that the car was his and I recall making a joke about why a tall man would want to drive such a small car.

I watch as Beatrice busily runs the taps of her deep Belfast sink to fill a vase and then plunges the flowers into it. ‘These are lovely, thanks, Abi,’ she says as she arranges the flowers. I notice some of the daisies have drooped over the side of the vase. ‘That’s kind of you to say you love this house. I think it’s quite special, but maybe that’s because of the people who live in it with me.’ She turns to me and flashes one of her amazing smiles and a lump forms in my throat when I think of my empty flat.

‘It’s a huge house,’ I say. How can an artist and someone who works in IT afford a pad as luxurious as this?

‘It is. Too big for me and Ben. So it’s nice that we’ve got the others living here too, although Jodie is moving on.’ An emotion I can’t quite read passes fleetingly over her face like a searchlight. I play with the necklace at my throat, waiting for her to elaborate. She looks as if she’s about to say something further then appears to change her mind. ‘Let me put the kettle on,’ she says instead. ‘It’s a pitiful day and it was so sunny at the weekend. Honestly, this weather.’

‘Is Ben at work?’ I ask. Her narrow back stiffens slightly at the mention of his name. I watch as she pours boiling water into two cups, pressing the teabags against the side with her spoon, her fair hair falling in her face, and I find myself longing to go over to her, to push her silky hair back behind her ear so that it’s no longer in her eyes.

‘Yes. He only works contract.’ Her voice sounds falsely jovial and it occurs to me that perhaps they’ve had a row. ‘I don’t completely understand what he does, but I do know it involves computers.’ She laughs as she hands me the mug of tea and pulls out a chair opposite me and sits down. ‘What about you, Abi? You said on Saturday you were a journalist?’ Even when sitting, Beatrice seems to ooze energy; her legs jiggle under the table, her elegant fingers tap the side of her white bone china mug. She takes an apple from the bowl of fruit in the middle of the table and indicates I do the same. I murmur my thanks and choose a dark-red juicy plum, but when I take a bite it is hard and sour.

‘I used to work for the features pages for one of the nationals, in London,’ I say through a mouthful of plum which I manage to swallow with difficulty. ‘That was before I got my dream job on a glossy magazine. But I’ve done my fair share of news too. I used to work at a press agency and spent a lot of time hanging around the houses of famous people or public figures. We call it door-stepping, although some might call it stalking.’ I laugh to show I’m joking but Beatrice smiles seraphically and I wonder what she’s thinking. She takes a bite of her apple and chews it slowly, thoughtfully. ‘But now I freelance and things are a bit slow,’ I add hurriedly, wanting her to forget the stalker comment.

‘Is money a problem?’ She looks at me with concern and my cheeks burn. Judging by her lovely expensive-looking clothes and this beautiful house, money isn’t a problem for Beatrice. I don’t want her to think that’s the reason I want to be her friend.

‘No,’ I lie. ‘My parents have said they will help out if I need it. And I can always go and live with them if I can’t afford to pay rent any more.’

‘I’ve had an excellent idea,’ she almost shouts, her eyes bright and her cheeks pink. ‘Why don’t you move in here?’

‘Here?’ I’m so shocked that I can barely form the words and almost choke on a piece of hard plum. Of course, there is nothing I’d want more than to move in with her, to be with her all the time.

‘Oh, it’s perfect,’ she says, jumping up and dropping her apple in her exhilaration. I watch as it rolls across the table, falling off the end on to the tiled floor. Beatrice ignores it and stares at me, an intensity that I haven’t seen before in her eyes. ‘I was so upset when Jodie said she wanted to move out. But it’s fate, it’s so you can move in here with us. I should have thought of it before. Durrr!’ She actually slaps her own forehead with her hand and pulls a silly face, making me giggle. Her enthusiasm is infectious and the thought of moving into this stunning house, living with people again rather than rattling around my empty flat makes me want to bounce happily around the kitchen. ‘Why don’t you come and view the room now? I think Jodie’s gone out. Oh, it will be such fun if you move in.’

‘But …’ This is all going too fast and my heart begins to race. I’m not sure if I can do this, if I can start living a normal life again rather than my current hermit existence.

‘There are no buts, Abi. We got on so well on Saturday. I was so nervous about the showing, but you made it such fun. You’ll come to love the other girls. Pam is larger than life and such a laugh, and Cass is a sweetheart …’ She holds out her hand. ‘Come on.’ She smiles. Her eyes are wide with excitement, making her look even more beautiful. I think of how great it would be, living with Beatrice and not being alone any more; it would be like having a sister again, and I can’t stop the smile spreading across my face.

‘You’re right,’ I say as I take her outstretched hand, allowing her to pull me gently to my feet. ‘It will be perfect.’ And I follow her out of the kitchen, leaving the sour plum on the table behind me.

Beatrice’s bare feet make a slapping sound on the stone steps as we climb the winding staircase and I touch one of the daisy-shaped coloured lights that have been wound around the banister, excitement building at the thought that soon this beautiful house could be my home. The heady scent of Parma violets hits me again and I’m aware it’s coming from Beatrice. It must be her perfume or the washing powder she uses for her laundry. Either way, it’s intoxicating.

When we reach the first floor I can’t resist poking my head around the door of the huge sitting room that runs the length of the house, remembering from Saturday the velvet squashy sofas, the artefacts that Beatrice has collected from her travels to places such as India, Burma and Vietnam, the French doors leading out to a large terrace overlooking the garden. I remember the frisson of exhilaration I felt, wedged between Ben and Beatrice on one of those sofas, wine glasses in hand, chatting away as though the three of us had known each other for years.

Beatrice stops halfway up the next flight of stairs and turns in my direction with a questioning rise of her finely arched eyebrow.

‘I’m only being nosey,’ I admit as she continues up the stairs. I fall in behind her. ‘And remembering Saturday night.’

She laughs her endearing tinkly laugh. ‘It was a great night – and there will be many more like it if you move in. Jodie’s room is up here, next to mine. And Ben’s room is opposite, next door to the bathroom. Then, upstairs we have two more bedrooms, the attic rooms, which Cass and Pam use. They have their own bathroom, thankfully, as usually one of them is ensconced in there, dyeing their hair. I expect you remember all this anyway, at the open studio event the other day.’

I nod, not wanting her to know how accurately I’ve memorized the layout of her house; then she really would think I was a stalker. We reach the landing, pausing outside one of the first doors we come to. It’s painted in a creamy white with a solid brass knob for a door handle. There’s no lock. Beatrice raps her knuckles gently against it. When there is no answer, she pushes the door. It opens with a lingering creak.

The room is so at odds with the rest of the house that it’s as if I’ve been teleported into a student bedsit. It smells of unwashed bedding and dirty clothes mixed with something acrid, chemical. I give a little start. Jodie is lying on the single bed that’s been pushed up against the wall to make way for two more ugly sculptures. She has huge earphones clamped on either side of her head, her eyes are closed and she’s quietly mouthing the lyrics of the song that she’s listening to. I can’t quite make it out, but it sounds slow and angsty. I survey the large room with its indigo walls blu-tacked with many posters of gothic bands from the early 1980s, the high ceilings and marble fireplace, and try to imagine it as my bedroom. Two sash windows that are nearly the height of the wall face on to the street below and the identical five-storeyed houses opposite. A silver birch in the front garden bends and stretches in the wind, its leaves casting dappled shadows on the grubby-looking carpet.

Jodie’s eyes snap open and she pulls the headphones from her ears.

‘Sorry, Jodie, I did knock,’ says Beatrice, not looking particularly contrite.

Jodie sits up and swings her legs over the side of the bed, glaring at us sullenly. She’s wearing a huge black T-shirt with a silhouette of Robert Smith on the front which makes her look about twelve. Her legs are pale, her calves adorned with so many moles they remind me of a child’s dot-to-dot drawing.

‘Do you remember Abi?’ says Beatrice. Jodie nods gruffly as I say hello, her bright blue eyes surveying me so intently it’s as though she can read my thoughts, that she knows all about me. My heart skitters and I mentally recall Janice’s words, the mantra she taught me to calm myself when I sense a panic attack coming on.

Jodie turns to Beatrice, her little face pinched into a frown. ‘I only told you I was moving out yesterday and already you’ve found a taker for my room.’ She gets up and steps into a pair of grey skinny jeans that are in a coil by her bed.

‘It wasn’t planned, Jodie. It only occurred to me a few minutes ago when I was chatting with Abi downstairs,’ says Beatrice casually, as she walks over to one of the gargoyle-esque sculptures. I might not know much about art but surely anyone can see her sculptures are hideous.

‘Is she an artist?’ she says, as if I’m not even in the room. When Beatrice shakes her head, Jodie’s frown deepens. ‘I thought you only let artists live here?’ I can sense the animosity emanating out of every pore in Jodie’s body. I stand awkwardly by the door, feeling like an intruder. Beatrice opens her mouth to reply but Jodie cuts her off with a shrug. ‘Whatever. It’s none of my business any more. I’ll leave you to it.’

As she stalks towards me I instinctively breathe in, but instead of walking past me to go out the door, she stops so that her face is inches from mine. ‘For some reason, she desperately wants you here,’ she says in a low voice. I glance to where Beatrice is standing on the other side of the room, examining the sculpture, running her hands over its beaky nose and making appreciative noises, much to my surprise. My eyes flick back to Jodie as she continues, coldly: ‘I’d watch my back if I were you.’ And then she storms off, leaving me staring after her in bewilderment.