Читать книгу Imperial Illusions - Kristina Kleutghen - Страница 44

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

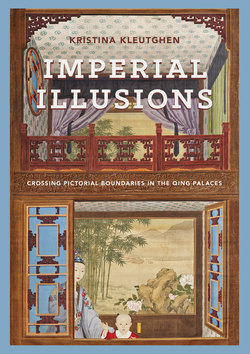

Оглавление1.3Wang Hui, Peach Blossom Spring following Zhao Mengfu’s (1254–1322) Methods of Using Color, leaf G from Wang Hui and Wang Shiming, Landscapes after Ancient Masters, 1674 and 1677. Album leaf, ink and color on paper, 22 × 33.8 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, The Dillon Fund Gift, 1989 (1989.141.4a-rr).

With these ideas as the new orthodoxy, little more than the names of a few muralists survive from the seventeenth century. Although at this time in Hangzhou one could still see murals believed to date as far back as the Tang dynasty,40 the dominant mode of seventeenth-century painting continued Dong’s ideas as further transformed by Wang Hui (1632–1717). Under the tutelage of Dong’s leading student, Wang Shimin (1592–1680), Wang Hui became the leading orthodox landscapist of his own generation by disagreeing with the exclusive privileging of Dong’s codified lineage, but never abandoning that heritage. Consequently, he created his own inclusive Great Synthesis of the brushwork and forms characteristic of many famous historical masters to blend mimesis and calligraphy, Yuan literati abstraction and Song professional realism, and what he called the “obscure” (an) and the “obvious” (ming) into nothing short of a landscape painting revolution.41 Wang’s work in this area is exemplified by a small album leaf painting, Peach Blossom Spring Following Zhao Mengfu’s (1254–1322) Methods of Using Color (figure 1.3), in which he employs the distinctive ropy but parallel “hemp-fiber” texture strokes (pimacun) characteristic of Dong Yuan (act. 930s–60s) and reinterpreted by both Zhao Mengfu and Huang Gongwang (1269–1354) to indicate the crevices of the rounded rocks, along with the archaic Tang blue-and-green landscape painting mode that Zhao Mengfu had also reinterpreted.42 Calligraphic strokes mix with vibrant colors in a dramatic juxtaposition of historical styles that would likely have shocked Dong Qichang, as the rich green of the hills contrasts with the lively pink of the blossoming peach trees to create a vivid image of the paradigmatic fantasy realm that still owes more to historical painting references then to the actual appearance of a spring landscape.43 Blue-and-green landscapes had long been associated with “visions of paradise or an antique golden age”; the application of a historical style to this particular subject of a magical world set apart from the real world therefore further separated the depicted landscape from nature and reality.44 By synthesizing certain nonliterati elements into the literati mode in his own way, Wang Hui integrated the pictorial past with his own originality in the present, but still relied on abstracted historical styles rather than accurate depiction based on nature.