Читать книгу Imperial Illusions - Kristina Kleutghen - Страница 53

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

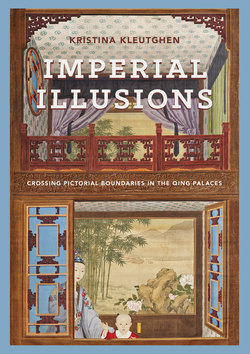

ОглавлениеAppropriating Western Painting at the Kangxi Court

Johann Adam Schall von Bell, S.J. (Tang Ruowang, 1591–1666), was just beginning to use a combination of Western art and science to make inroads at the Ming court when that dynasty fell in 1644 due to an internal rebellion. The rebellion was subsequently quelled with assistance from the Manchu Qing dynasty, which had established itself well north of the Great Wall in 1636, but the Qing then succeeded the Ming to become the new foreign rulers of China. Beginning his work anew with the Shunzhi emperor (r. 1644–61), Schall von Bell became first a scientific advisor and later a personal mentor to the young ruler, thereby succeeding in establishing the Jesuits as both scientific advisors and imperial teachers of Western learning (Xixue). Shunzhi’s heir Kangxi demonstrated deep interest in the various branches of European knowledge that made up the Renaissance scholastic quadrivium of arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. Ferdinand Verbiest, S.J. (Nan Huairen, 1623–88), who assisted and later succeeded Schall von Bell as the director of Beijing’s astronomical observatory in 1669, noted that linear perspective played a key role in the mathematical sciences taught at the Qing court.66 Although a painting technique, linear perspective was introduced as part of geometry and therefore was presented less as an art than as an aspect of technical knowledge. Along with established literati painting values, this scientific nature was likely an important part of what prevented its visual dialogue with Chinese painting in the seventeenth century,67 but also what made it attractive to the Qing court as part of new knowledge that supported Kangxi’s statecraft, and which he supported in turn by sponsoring a number of texts in both Chinese and Manchu on Western learning. Such study, patronage, and control of this technical knowledge was a dramatic departure from previous imperial and literati practices, which avoided direct engagement with such subjects, and has been interpreted as a means of demonstrating political authority by mastering knowledge not common among the literati scholar-officials who dominated the civil bureaucracy.68 The specialized knowledge Kangxi gained by studying mathematics, astronomy, and other subjects with the Jesuits was therefore an essential part of his statecraft, which positioned him as both a powerful ruler in full control of the empire and a teacher who embodied the Confucian ideal of the sage-ruler who was wiser than his subjects. Such a presentation was particularly important given that Kangxi had come to real power only by overthrowing his regents while still a young teenager, and had spent the first decades of his sixty-one-year reign brutally consolidating the Manchu-led empire against pro-Han Ming loyalist rebellions in southeastern China.

To help improve the Han majority’s perception of the Manchu Qing rule, establish support among the literati, and strengthen his self-presentation as a legitimate Confucian ruler, Kangxi followed an ancient precedent and undertook a series of imperial inspection tours.69 The most important were his six Southern Tours (Nanxun) through the Yangzi River delta, where Kangxi sought new officials from among the unparalleled