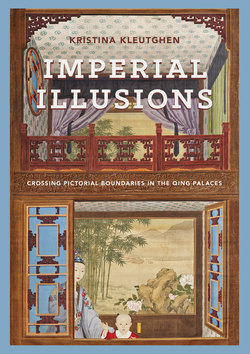

Читать книгу Imperial Illusions - Kristina Kleutghen - Страница 76

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеexperience in such estimates and calculations: perhaps the valuable substances he includes in the tables concluding the Brief Guide reflect that experience. He also would have needed to quickly calculate the material needs for porcelain production, such as amounts and costs of clay and pigments, the number of pieces that could be fired at one time in the kilns, how many pieces could be loaded on to a ship for export, and so on.35 With such a “practical studies” approach to understanding the mathematics of three dimensions, Nian’s approach to illusionistic Western painting is therefore precisely what one would expect from a mathematician. The Brief Guide and The Study of Vision are thus two approaches to the same subject: explaining and transmitting the technical knowledge required to understand and represent three-dimensional objects, although one representation is numerical and the other pictorial. To paint those objects in the same three-dimensional way that he perceived them, Nian simply needed to apply many of the same mathematical concepts to images. Nian’s two 1735 treatises, published only three months apart, demonstrate how he integrated his personal interests in Western mathematics and art by applying the precision and procedures of mathematics to painting by using measurements, calculations, and technical drawing tools. As distant as logarithmic calculus might seem from perspectival illusionistic painting, in Nian’s presentation they are two sides of the same coin, fundamentally related approaches to understanding one’s cognitive experience of the phenomenal world.

The Study of Vision

In the final lines of Nian’s entry in the Biographies of Astronomers and Mathematicians, Ruan Yuan writes that among Nian’s papers at his death was “an anonymous manuscript, entirely handwritten, with text as well as pictures [tuhua], which is also extremely elegant [bing ji jingmei],” which Ruan suspected that Nian had authored. Vague though Ruan’s comment may be, it notably does not describe the manuscript as having specifically mathematical content, and includes the tantalizing clue of illustrations alongside the text. It could not be the illustrated Brief Guide, which is listed individually. This mysterious manuscript, therefore, may well have been one of Nian’s two illustrated nonmathematical publications, which are not listed in the biography: The Essence of the Study of Vision and The Study of Vision. The latter has survived intact, but the former, an early shorter version of the same treatise, exists only in one fragmentary copy.36 That does not diminish the fact, however, that Nian twice published on the subject of pictorial illusions, demonstrating his enduring interest in the topic.

The Study of Vision comprises the original 1729 prose preface and a new additional preface dated to 1735, followed by 141 pages of illustrations that Nian refers to as tu. This term has been translated as “technical images” for the nonaesthetic knowledge encoded in such pictures, and tu have been described as “templates for action” that functioned together with nearby text to produce technical knowledge.37 Such images, which can be