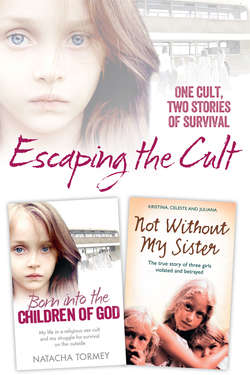

Читать книгу Escaping the Cult: One cult, two stories of survival - Kristina Jones - Страница 17

Chapter 7 Torn Apart

ОглавлениеThe Children of God might have renamed themselves The Family in a bid to make some kind of point about communal values, but when I was seven we came to learn just how little families like ours really meant to them.

It was early morning, when the tropical heat was at its most bearable. Birds sang their wake-up calls, swooping onto the flame of the forest tree with twigs in their mouths ready for nest building. A red-and-yellow butterfly fluttered down and paused on my hand before flying away. I watched it go before turning back to the confusing scene on the driveway.

An uncle was loading Leah and Thérèse’s scarce possessions into the minivan. My mother and Leah were standing next to it, hugging each other. I didn’t really understand what was going on but I had a sense it was very bad, and because Mom and Leah cried it was only natural I did too.

My brothers hung near them, trying to cling to Leah’s legs. With a determined look on his face Marc climbed into the van, picked up the bags and started to carry them back towards the house. The uncle grabbed them and put them back into the van.

‘No, no, no.’ Marc flung himself at Leah from behind, gripping onto her as if his life depended on it. My mother walked behind, gently trying to prise him away, but he screamed and clung even tighter.

My parents had been ordered to a new commune in Bangkok; Leah and Thérèse had been ordered to a different city. Leah was highly valued as a flirty fisher and she was still technically single because, although in a committed relationship with my father, she wasn’t married to him. In short, her assets were too useful for her to be allowed to stay in the threesome any longer.

The senior Shepherds who made the decision had sprung the news on us while my father was away on a mission, denying him the chance to say goodbye to his long-term lover and their daughter. As the minivan prepared to drive away with my beloved baby sister in it, I pressed my face against the window and blew a kiss to Thérèse, who had tears rolling down her tiny cheeks. She was just six. I was seven. As I waved goodbye I could never have imagined that it would be a decade before I saw her again.

We weren’t the only family to be broken up in such a brutal way. Siblings were sent away, married people separated, older children ripped from their parents – all on the whims of the leadership. I had heard my older brothers talking about how the mother of a friend of theirs had left The Family by running away in the middle of the night. She came back with some men a few weeks later to try to kidnap her son, but the Shepherds had been expecting her to try it and had already sent him to another country so she couldn’t find him.

My dad was still a Regional Shepherd but was beginning to see his authority wane. David Berg was paranoid about anyone becoming too powerful or challenging his dominance. As such he created a management ethos based on game playing, backstabbing and blame. Even at local leadership level it was impossible to get too comfortable in your role because it seemed that however hard you worked or how competent you were it was never quite enough. Dad had been a Shepherd for over ten years now, and some may have felt that was too long.

The night after Leah and Thérèse left was horrible. My mom looked pale and in pain, the boys wouldn’t stop crying and I was completely confused, still half expecting them to come back in through the door. Then we had the added turmoil of knowing that we were also on the move at the crack of dawn. Mom tried to be positive about it, saying that as Dad was in Bangkok so often anyway it was a very good thing because we could see much more of him.

I was sad to leave some of my friends but I was pleased to see the back of that place.

By 7 a.m. we were on the road, a ragtag family in a battered minibus, a few bundles of clothes our only possessions. The roads were winding and rough, which made me feel so ill we had to stop the car twice for me to vomit by the side of the road.

As we reached the outskirts of Bangkok I thought we had driven into hell itself. It was a terrifyingly teeming, bustling, overwhelming city that made Phuket look like a tiny village. I had never seen so much traffic or heard so much awful noise. At the traffic lights a man in uniform banged on the window. I saw his uniform and screamed: ‘Antichrist!’

‘It’s OK, ma chérie. He’s just a system policeman. He was only helping us through the traffic,’ explained my mother.

Her words did nothing to help me understand. I’d always been told the systemites in uniform were the Antichrist’s followers and were the most dangerous of all. When the End Time came they were the very people who would want to kill us. So why was it that whenever we went outside my parents spoke to them?

Once we’d traversed the city centre we reached a suburb on the far side. We turned off down a dusty unmade road, surrounded by boggy fields mostly, with a few half-constructed villas along the side. After a kilometre or so we arrived in front of a house with a large red metal gate and a high concrete wall with broken splinters of glass sticking out the top. We beeped the horn and the gate swung open to reveal our new home, a two-storey concrete building with a cluster of smaller one-storey buildings set around a central courtyard. I was disappointed to see there was no beautiful flame of the forest tree here. There was hardly any garden at all, just a few bedraggled shrubs here and there. Virtually all the space had been given over to the buildings.

We walked into a mess hall where over 150 people were eating lunch in silence. They all turned to stare at us. No one got up to say hello. I started to cry, grabbing at my mother’s skirt. ‘Mommy, I want to go back home.’

She bent down to reassure me just as a strange uncle walked up and gave us instructions about where we would sleep. My mom didn’t even have time to hug me before he announced her ‘mission’ was as usual to work in the nursery looking after the babies. He picked up her little bag and started walking through the hall, waiting for her to follow. When she hesitated he snapped rudely at her: ‘Come on then, I haven’t got all day.’ The pair disappeared out of view.

My brothers and I stood there waiting uncertainly for another ten minutes. The older boys stood with ramrod-straight backs, outwardly calm but watchful and aware. I got the impression they were as worried as I was but that they were trying to look strong for Vincent and me. I followed their lead by holding onto Vincent’s hand, hoping it would make him feel better.

The uncle came back. My eldest brother, Joe, found his voice, politely asking: ‘Excuse me, Uncle, but please can you tell me where my father is? Is he here?’

‘Yes,’ replied the man. ‘He’s busy with his work in the Shepherd’s offices. You will see him later. Don’t bother him now.’

He gestured for us to pick up our bags and follow him. As we walked he explained that all children slept in age-related dormitories. The dorms were as follows: YCs (younger children), MCs (middle children), OCs (older children), JETTs (Jesus End Time teens), JTs (junior teens) and STs (senior teens).

I was put in the MCs and Vincent the YCs. ‘I want to stay with Tacha,’ he pleaded to the uncle but the man barely even glanced down at him before handing him over to the aunty who ran his dorm.

The MC dorm was crammed with over a dozen double and triple bunks, with extra trundle beds on wheels underneath the bunks. The uncle pointed to a bottom bunk with a thin foam mattress. On one wall there was a large freestanding cupboard with several drawers. He picked out a tiny drawer in the middle where I was instructed to store my spare set of clothes.

The rest of the day passed in a haze of anxiety. As I climbed onto my new bed no one spoke to me, although several children stared at me blankly. I felt wretched, wishing so badly my mom would come and cuddle me. I thought about Leah and Thérèse. With the optimistic logic of a child, a little bit of me had hoped they might be waiting for us in Bangkok. With the final realisation they weren’t, I cried myself quietly to sleep.

I was woken at 6 a.m. by a completely naked aunty ordering us into the bathroom with her. The bathroom was large, with a basic Asian style shower – an oil drum full of water in the corner, a plastic bucket and a jug to splash water over ourselves. The other kids still ignored me. They had hollow, weird eyes that made me feel creepy. I was too scared to say anything to them. After the shower we all dressed in silence and marched single file into the mess hall for breakfast.

After breakfast my schooling regime was explained to me. The routine here was much more regimented than it had been in Phuket. The day was a constant round of Word Time (studying Grandpa’s teachings), followed by Memorising (memorising Grandpa’s teachings), Jesus Job Time (housework such as scrubbing floors or washing dishes), School Work (which wasn’t academic but involved more of Grandpa’s teachings), preparing for the End Time and Quiet Time (forced nap time).

At all times children were forbidden to talk without permission. That was also the rule in Phuket but even the likes of Clay and Ezekiel, as terrible as they were, didn’t usually bother to enforce it. Here was different: I found to my cost that even a stolen whisper to my brother in the mess hall resulted in being sent ‘to the wall’, where you had to stand with your nose to the wall for up to an hour without moving. The first time it happened to me I got horrible cramps in my back and leg but when I moved I got a spank.

A few days after we moved in, the home began its annual ‘fast’. All communes in The Family fasted for three days leading up to Berg’s birthday, which was a day of ecstatic celebration for his followers. The entire house fell into what felt like a state of mourning. All daily operations, fundraising and events were cancelled. A few adults took care of the children and cooking in rotating shifts while the others spent 72 hours in prayer vigils, inspiration time and reading dozens of long letters from Grandpa. During the fast they were allowed to eat only liquid foods. I remember the large bowls of soup and a gooey pale orange mix of papaya blended with yogurt that sat on the counters in the dining room as the adults filed by us in complete silence, almost as if in a trance. Pregnant women and children were exempt from fasting, although we little ones had to spent extra time reading Grandpa’s letters and praying. Every evening the home would gather together for inspiration time, which was twice as long as normal. To me it seemed like endlessly dull hours of singing with the incants of praying in tongues floating through the house. It only served to add to my unhappiness at being there.

Within a couple of weeks I had begun to make friends – a boy called Noah and two sisters, Faith and Mary. Our friendship didn’t amount to much more than exchanging smiles or silently taking a place next to theirs in the classroom. But just being able to sit next to a child I knew wasn’t hostile helped me feel more settled. After a few weeks of being there I was beginning to sleep more easily. My all-pervading of fear of Clay was fading. My new bed was far from cosy but I took a certain reassurance in sharing the room with so many kids. That night I climbed in and fell straight to sleep.

‘Inspection time, MCs,’ the voice startled me awake. I could make out the silhouettes of an aunty and uncle who had come into our room. Disoriented, I thought for a minute they meant a tidy bunk inspection, and I was very confused as to why this was happening in the middle of the night instead of before breakfast like usual. I had clambered half-way out of my bed before it dawned on me I was the only one doing so. Two boys in the bed opposite had rolled over onto their fronts, faces buried in the pillow. My first thought was that they were going to be in trouble for ignoring the inspection. But then the aunty leaned over one of them and pulled down his pyjama bottoms as the uncle shone a torch. She took something and put it in his bottom. She pulled his pyjamas back up and moved to the kid above. I stared wordlessly as they moved methodically from child to child, repeating the process. No one was crying. As they reached my bed memories of Clay flooded back and I pulled the sheet up to my chin, shaking my head. The aunty looked surprised and turned to the uncle. He smiled. ‘She’s the new kid. Patience’s daughter. They probably didn’t have good cures in their old house.’

‘Ah, got you,’ said the aunty. She looked at me kindly. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Natacha.’

‘Hi, Natacha, I’m Aunty Rose. This is Uncle Zac. There’s no need to be scared, sweetie. We’ve come to give you all some medicines. You need them so you don’t get sick.’

‘I’m not sick.’

‘I know you’re not. Not yet anyway. But if you don’t take the medicine you might be. It’s good for you.’

‘Why?’ I was surprised at my own boldness.

‘OK, honey, have you heard of worms? Do you know what worms do?’

‘Yes, they live in the ground.’

‘They do. Some of them. But some of them live inside little children. They live in children’s tummies and they grow bigger and bigger and bigger until they give you a nasty tummy ache. I want to give you some medicine to stop the worms getting inside your tummy. It’s a lovely God-given natural cure to keep the nasty worms away. Can I do that?’

Still staring mistrustfully, I nodded silently.

‘OK. I promise it won’t hurt. Turn over, sweetie.’

With that she placed a large garlic clove inside my bottom.

She lied. I was so uncomfortable I couldn’t get back to sleep afterwards. Nor did it do anything to prevent worms. Loads of the kids had them.