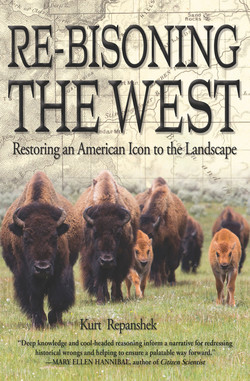

Читать книгу Re-Bisoning the West - Kurt Repanshek - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Landscape

The region, once labeled “the Great American Desert,” is now more often called the “heartland,” or, sometimes, “the breadbasket of the world.” Its immense distances, flowing grasslands, sparse population, enveloping horizons, and dominating sky convey a sense of expansiveness, even emptiness or loneliness, a reaction to too much space and one’s own meager presence in it.

—Encyclopedia of the Great Plains

The Great Plains is a topographical tabletop, one about five hundred miles east to west and two thousand miles north to south. Though not as flat as a table, the region nevertheless lacks a substantial range of mountains like the Appalachians, the Rockies, or the Sierra. It quite understandably could have developed an inferiority complex, for the East and West coasts urbanized much more quickly than this heartland, and across a much greater area. It took the 1862 Homestead Act, a legislative tool for encouraging the nation’s westward expansion, to see what was possible out on the Plains. But for more than a few, taming this landscape proved impossible. Even today, more than 150 years after the Homestead Act ignited a land rush where settlers who could tame 160 acres of land for five years received it free and clear, the Plains are a tough place to live.

This is a breathtakingly wide expanse of land, as I discovered after graduating from college. Determined to see, and more specifically ski, the Rockies, I stuffed my few belongings into the back of my boxy 1978 Subaru wagon and headed west from New Jersey, only to run into the Plains on the other side of Missouri. I didn’t find many trees to slow the wind or soften the sun’s glare. Park your car along I-70 after leaving Topeka, Kansas, and stand on the highway’s shoulder and you’ll be awestruck by a setting that runs to, and then bends off, the horizon in all directions. Touching all, or parts, of a dozen US states, the roughly five hundred thousand square miles within the Great Plains province wash ashore at the foothills of the Rockies on its western edge and dip into the Missouri River on its eastern boundary. But it is bigger still, two thousand miles north and south, extending from the prairies of Canada’s Alberta, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan provinces, all the way south to the banks of the muddy Rio Grande River.

Stand on the Wyoming prairie, or on that in Kansas, the Dakotas, Nebraska, or Oklahoma, and the open country flees from you in all directions. The plains cower from the Rocky Mountain Front in Colorado and Montana, but only in physical relief. There are no majestic peaks here, and yet, the Great Plains, with sun beating down, scant water, and seemingly perpetual wind, is as demanding a place as one of Colorado’s fourteeners for those unprepared.

When I first ventured into the Great Plains, a young man making his first encounter with what lay west beyond West Virginia where I spent my college days, the contrast in landscapes was startling. Behind me were heavily treed mountains with leaping streams. Spread out before me were endless, mountainless plains rolling in all directions. A sea floor without the sea. Cattle, not bison, dotted the prairie on either side of I-70 for much of the 603 miles from Kansas City all the way to Denver.

To begin to appreciate this landscape, you must understand how it came to be. The Rocky Mountains, and even the Appalachians, are easier to admire and grasp than the Great Plains because of the sheer bulk that they send up and the geology that they expose. The Great Plains is a subtler region, or physiographic division, as topographers would tell you, one in need of both a geologic and geographic primer. North America’s geologic contortions imbued the Plains with rich soils. During the Cretaceous Period more than sixty-five million years ago, an immense inland sea, the Western Interior Seaway, sloshed across the region. Into its warm waters sank the organic detritus of fish, amphibians, reptiles, seaweeds, and any land-rooted vegetation that was washed into the sea. Then came the slow ratcheting up of the Rocky Mountains. Geologists continue to puzzle over the exact mechanism that served as the jack, but some speculate that as the oceanic tectonic plate was forced to the east it didn’t sink deep below the North American plate, but took a shallower pitch. As it did, it pushed up the mountains, much as a throw rug scooches up when your foot catches the edge. These riveting mountains, with their steep, canyon-incised flanks, drained rains and snowmelt through the foothills, carrying soils and other vegetative flotsam into rivers that then deposited them on the Plains. As the Cretaceous faded after its seventy-nine-million-year run and transitioned into the Paleogene, and it into the Neogene, the evolution brought glacial episodes with towering rivers of ice bulldozing additional soils and silts into the region. They even remodeled the landscape in places. Streams were pushed into different directions; the mighty Missouri River was shunted roughly 180 degrees, shoved away from its northward flow and sent off to the south.21 All the while, more sediments were carried to the region on the breezes. Mineral-rich grains blasted into the sky by volcanic eruptions rode the winds to the Great Plains from the Great Basin far to the west.

Prehistoric life became imprisoned in this geology. Microscopic plankton, both from flora and fauna, that were buried deep by other layers of sediments and eventually placed under great pressure and heat, turned into oil and natural gas. Dinosaurs turned into fossilized remains. The fossils in the Plains led to the great bone wars of the nineteenth century in places such as southern Wyoming, Colorado, and Nebraska, while the oil and gas continue today to be pulled from below the Plains states for energy. All these geologic perturbations over tens of millions of years produced an incredibly diverse topography. Along with the Missouri, the Milk, Yellowstone, Powder, Cheyenne, Platte, and Dakota rivers carve through the country. So, too, do the Medicine Bow, the Tongue, Arkansas, and Niobrara rivers. Mountains are not a hallmark of the Plains, but a few provide geographic relief, poking up as inland islands above the prairie sea. Along with the Black Hills in today’s South Dakota and Wyoming, there are the Snowy (Big and Little) and Judith Mountains in Montana, as well as the Little Rocky Mountains. But that’s about it.

This is a very big place with a very complex personality. Despite its identifying name, the Great Plains is not self-defining, is not solely a flat, mid-continental placeholder. It climbs in elevation from a reasonable two thousand feet above sea level to a lung-testing—for true flatlanders—seven thousand feet. It embraces the rolling hill country of the Black Hills, the flat prairies with “amber waves of grain” that stir in the breezes that sweep Kansas and the Dakotas, and even the volcanically puckered landscape of eastern New Mexico. Steady erosion for the past five hundred thousand years sculpted the intricate formations found in Badlands and Theodore Roosevelt national parks.

Patches of ponderosa pine forests, buffalo grass and wheat-grass prairie, a mix of bluestem and sandsage prairie, and even oak-hickory forest appear along the eastern edge of the Great Plains. There are expanses of fescue prairie, sections of mesquite and aspen, and some juniper-oak savanna.22 There are draws, washes, gullies, ravines, coulees, arroyos, and canyons. Topographical quirks—cliffs and sinks—were used by Native Americans when it came to hunting bison. Bison herds would be chased by the hunters up to, and then over, these geologic “jumps” to their death. These death traps still stand out today near Chugwater, Wyoming, and on the Sanson Buffalo Jump within Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota. Some outcrops run a mile in length and stand fifty feet tall, and many are still littered with bones.

But the “plains,” the mostly flat sections, are what come to mind when you hear the term uttered. At first glance, this can appear to be a desolate place, especially if it’s winter and a thirty-mph wind blows snow in your face, or if it’s summer and the cloudless sky offers no relief from the hundred-degree heat. Trees are few and far between in the heart of the Plains, too. Instead, you’re greeted by a mix of shortgrass and tallgrass species that are the dominant vegetation. The eastern slash of the Great Plains province that greeted whites three centuries ago gained a bit of height and structure with switchgrass that reached ten feet into the sky, and big bluestem, another prairie grass that rose eight feet above the soil. During the growing season, asters and sunflowers brought more color and some height. Perennial bunchgrasses still today are found in most, if not all, states east of the Rockies. Along with providing forage for bison, pronghorn, and deer on the Plains, the grasses offer cover and nesting habitat for a variety of bird species. Ample rainfall drives the vegetation’s growth. These plant species anchor deep root networks, locking the soil in place while also adding organic matter that encourages farming. On the more arid western half of the Plains grows sagebrush and grama-buffalo grass, the latter a runt compared to switchgrass and big bluestem. While it can struggle to reach ten inches in height, the buffalo grass carpets the prairie with a rich mix of other grasses: western wheatgrass, needlegrass, bunch-grass, and fescues.

Walk the prairie and, if you come after a soft, pattering rain, with the clouds clearing and the sun streaming through, the essence of the landscape rises up. Breathe deeply and fill your lungs with it. The moist air wicks up the pungent scent of sagebrush. As you stride through acres of this woody shrub, your legs brush the branches and their aromatic leaves release an indelible piquant fragrance. If you’re on the far western edge of the Plains, or perhaps in the Black Hills, you also might inhale a sweet, piney bouquet courtesy of ponderosa pines. Along the Plains’ eastern half, there might be a buttery scent, from prairie dropseed. All this vegetation, as it always has, provides food and habitat for pocket gophers, prairie dogs, and prairie chickens. They, in turn, are prey for black-footed ferrets, swift foxes, coyotes, bobcats, ferruginous hawks, golden eagles, and other raptors. Pronghorn antelope—North America’s fastest creature, able to accelerate to fifty-five mph in prairie sprints—and white-tailed deer rove the Plains as well. A mysterious herd of elk drifts through the Red Desert dune fields of southwestern Wyoming.

A well-aged, faded map hanging on a wall in my home locates the many native cultures that historically called the Plains home. People now known as Kickapoo Shawnee, Omaha, and Winnebago lived on the eastern edge where the states of Minnesota, Iowa, and Missouri have been carved out of the country. The Mandan, Brule, Ponka, Yankton, and other Sioux communities made the middle of the Plains home, while the Crow, Gros Ventre, Blackfoot, Shoshone, and Assiniboin peoples claimed the western side. Cheyenne and Arapahoe people also lived on part of this landscape, as did the Minnetarees.

For tens of thousands of years, and still today, the largest animal on this landscape has been the plains bison, known to most people as buffalo. Biologists classify the species as Bison bison, or even Bison bison bison. But the animals were tagged as “buffalo” by the coureurs de bois, the French-Canadian trappers of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. The name stuck with the voyageurs, fur traders who worked for the Hudson Bay Co. and the North West Co. and who called beef boeuf. Whichever name you choose, these animals are impressive to behold. Spend enough time in the Plains states and exploring their landscapes and you’re bound to encounter bison. Growing up in New Jersey, the only bison I encountered were pictured in magazines and sequestered in zoos. Not until my first visit to Yellowstone, in the mid-1980s, did I see bison in the wild. Driving through the park’s Hayden Valley for the first time is an experience you don’t forget, both because of the hundreds of bison and the traffic jams. Why some people think the hulking animals are tame is impossible to answer. Even after stopping at one of the park’s entrance stations and being handed a flyer warning them of the unpredictable nature of bison and how they like their space—move closer than twenty-five yards to these animals and you could be ticketed by a ranger—visitors pull over and park on the road’s shoulder, get out with their cameras and, with each successive shutter click, take a step or two closer to the bison that seems so small in the viewfinder. Or they’ll remain in their vehicles, slowly inching forward in the “bison jam,” and roll down their windows to snap a close-up of the bison alongside their rig. Rangers try to stop these behaviors, knowing full well how unpredictable, cantankerous, and dangerous bison can be.

There are times when the bison come to you, as was the case with my experience camping near Lone Star Geyser. I’ve also shared a campground with them in Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota. Crawling out of my tent one morning, I found about a half-dozen bison milling about the Cottonwood Campground. Some were munching the green grass for breakfast, while a big bull was using a tree as a backscratcher. Later in the day, while hiking toward Wind Canyon, I watched as a herd spilled through a mountain pass and rumbled down into the canyon. Standing on the trail, I knew that this scene had been repeated across the Plains for thousands of years. Bison close-ups also abound in Wind Cave National Park, and there’s little that compares with watching small bands moving freely across the prairie, or grazing the flats above the Snake River in Wyoming as the morning sun’s rays paint the Tetons.

You don’t easily confuse bison with cattle. Bison are taller at the shoulder and greater in girth, woollier, and not often swayed or intimidated by human onlookers. In Yellowstone’s expansive Hayden Valley, herds of bison loll about at midday, chewing their cud, swatting flies with their tails, gazing about. And of a sudden, they’ll take up en masse and move in late afternoon, browsing slowly as they go. As the tourist traffic slows on the Grand Loop Road and then stops, often in the middle of the road, cameras snapping and rolling, bison keep moving. Driving by these shaggy animals, they do look tame, and even willing to let you reach out your vehicle’s windows to scratch behind their ears. It can take a concerted effort to spook the big bulls and cows, who seem to consider us with disdain, an inferior species. An Oregon man discovered this in August 2018 when, emboldened very possibly by a fermented beverage or three, he got out of his vehicle and pranced and preened and hooped and hollered, taunting a bison that was slowly moving across the park road. When the bison finally half-heartedly charged him, the man somehow managed to avoid the animal. He was not lucky enough, however, to evade law enforcement rangers, who arrested him two days later at the Many Glacier Hotel in Glacier National Park where, rangers said, he again was taunting, but this time with other human visitors. A few weeks later Raymond Reinke, fifty-five, of Pendleton, pleaded guilty to four charges, including one for having an open container of an alcoholic beverage in his vehicle and another for disturbing wildlife. He was handed a 130-day jail sentence, a bargain compared to what he might have encountered on the end of the bison’s horns.

Most people who view bison do it sensibly, from a distance. It’s usually a subconscious, or even conscious, matter of self-preservation. Even though the modern-day bison are smaller than their Pleistocene ancestors, they still are imposing at more than six feet tall at the shoulder, ten or more feet long from nose to rump, and weighing as much as two thousand pounds as adult bulls. Females are roughly half as large, which is still too large for you to mock within striking range.

Why add more bison to the landscape? Because they belong there. They once were an integral part of the landscape. They evolved with it, tilled it, manipulated it, engineered it. They were then, and remain today, ecological engineers. They mow the land differently than domestic livestock, often in a healthier fashion if they are left alone. Bison don’t graze as hard as cattle; instead, appearing finicky, they browse and move frequently. The grass always is greener over there. Grazers such as cattle and sheep nip the vegetation off at or near ground level, while browsers like bison eat green stems and leaves. As a result, they leave behind grasses of varying heights, while the grazers often settle in for their meals and leave stubble in their wake. Bison also tend to pass over forbs, a choosiness that increases plant diversity. They spend less time than cattle around water sources, and so don’t trample riparian areas or graze the surrounding vegetation down to the ground. All things being equal, cattle will spend hours around water; bison take a drink and move on.

These big animals don’t require dietary supplements to remain healthy or to pack on weight for market.23 They’ll move with the seasons across their habitat. Some herds historically moved as much as two hundred miles to retreat to lower elevation winter habitat with lower snowfall, and so less work for a meal. That big hump on their backs? It is a mass of muscle that evolved as bison plowed their heads through the snows of winter to reach summer’s leftover meals. When driven by hunger, these animals can shovel through eighteen inches of snow with their heads.24 Hunger can be a powerful motivator, as bison generally require a daily diet of thirty pounds or so of grasses, sedges, willow, and even the occasional wildflower, such as a bouquet of scarlet globemallow.25

Their size, and tendency to group together against threats, makes it hard for wolves to take healthy bison down. Elk and deer are much easier prey. Still, some wolves in Yellowstone’s interior have figured out how to survive on bison. The Mollies pack, whose territory is deep in the park’s Pelican Valley, is the only pack that regularly preys on bison. That choice was in part due to the fact that while elk leave the park’s interior for lower-elevation wintering grounds, these wolves stay behind to endure the winter along with the bison that stay put. The wolves have figured out how to take down bison, usually without getting injured or killed in the process. But it’s still not easy. While the predators can kill an elk in roughly four minutes, it can take fourteen hours for fifteen wolves to kill a bison.26 Elk run, hoping to outdistance wolves. That leaves them defenseless to predators looking to hamstring their prey. Bison, however, stand their ground and rely on their horns and hooves for defense. The resulting need for more muscles, and the protein-rich diet of bison, has produced wolves in the Mollies pack that are 5 to 10 percent larger than wolves that concentrate on elk down along the Lamar River. One male measured by researchers weighed nearly 150 pounds.

Wolves might be the consummate killing machines in the wild kingdom, but bison are the apex creatures. Everything about them affects all other life-forms on the Plains. Their habit of rolling on the ground to shed fur, crush biting flies, and, for males, embed their scent in the dirt, creates “wallows,” small craters in the earth. These wallows are no small depressions, and at times bison might seem fastidious in creating them. Some bulls will seek ground softened, perhaps thanks to a seep or rain puddle, and then thrust a horn into the dirt like a pick. With growing vigor the animal then drops to the ground and uses both horns as well as the hump on his back to grind his desired indentation into the earth.27 Repeated use by any number of bison can grow some wallows to about nine hundred square feet—roughly the size of half a volleyball court.28 And because wallows are returned to again and again by bison that squirm about on their backs, grating their spines, humps, and flanks into the ground, the dirt is compacted. The result, when rains come, is that these depressions can turn into ephemeral water holes. These oversized puddles are used by the Plains spadefoot toads as nurseries, they nourish wetland plants, and they can even influence runoff. Botanists for the National Park Service have found that wallows can aid prairie plants that grow in moist settings and that, overall, they contribute to prairie biological diversity since their size, shape, and water-retention capabilities attract different grasses and forbs. Miniature wetland gardens, if you will. National Park Service researchers calculated that at the pinnacle of the bison population there might have been more than 1.5 billion wallows. Some of these relic depressions can be seen from the air today.29 In some areas, once you know what to look for, you can find yourself surrounded by them. You won’t find them in cattle pastures. Cows don’t wallow.

Bison are not averse to showing wolves a thing or two about dominance. In 2002, researchers in Yellowstone watched bison drive wolves away from recent kills the wolves had made, and saw a herd of nearly forty bison chase off eleven members of the Druid Peak pack that had pulled down a cow elk. The bison then surrounded her to keep off the wolves. Another time, onlookers watched as a half-dozen bison repeatedly scattered eight napping wolves.30 Videographers in the park even captured a week-old calf hold off an attacking wolf long enough for mom to arrive.31 And, at a state park in Florida, a bison was photographed running off an alligator. Some Yellowstone visitors have experienced the temper of bison firsthand, having been gored and even flipped into the air by those that they approached for photos too closely.

Bison are community builders, too. The grazing of their herds assists prairie dogs in building their colonies, and provides nesting habitat for the melodious western meadowlark, chestnut-collared longspur, and other songbirds. Explore prairie grasslands and you’ll find the mountain plover, lark bunting, and ferruginous hawk. More than three dozen bird species are associated with grasslands once tended to by millions of bison.32 Some birds have something of a symbiotic relationship with bison. Starlings and cowbirds will hop a ride on the back of bison, in part to be close by when the animals kick up insects out of the prairie grass, and also to pluck insects out of the fur they’re clinging to. It’s also thought that there is a collaborative relationship between bison and prairie dogs, as the dogs’ constant nibbling on grasses in their sprawling colonies spurs fresh growth, even into the fall, that bison relish.

Through their grazing, bison also stimulate vegetative growth, and they inhibit the spread of woody vegetation by rubbing not just their horns on shrubs and trees but their entire bodies as they scratch a massive itch. If there are no trees around, a nice boulder will suffice. The grazing habits of bison created de facto firebreaks on the prairie, as flames would run up to the vegetative mosaics bison formed with their shifting meals and sometimes stall, diverting into areas with heavier vegetative fuels.33 While bison cows can live to twenty years—with many of those years prime for producing offspring—males are into old age by their twelfth year. Hard winters with deep snow can quickly cut those limits.34 But even in death bison give to the landscape, their bodies feeding wolves, bears, coyotes, and the various scavengers that trail those predators, and returning nutrients to the soil, nourishing fungi and microbes.

On North America, the descendants of Blue Babe eventually separated into two subspecies, the plains bison and the wood bison. The two are similar in appearance, though the plains bison are a bit smaller and stockier with thick “chaps” of hair down their forelegs. The taller, more angular wood bison carry a more square hump, have a darker pelage, and tend to have straighter, less frizzy hair on their heads. While Yellowstone is home to the largest wild herd of plains bison, Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park claims that distinction for wood bison. But outside of national parks and some state parks, the loss of grasslands to settlement and agriculture has affected many of these species. Bison, of course, have lost vast landscapes they once roamed at will. So, too, have black-footed ferrets, small, slinky, carnivorous cousins of weasels, that were thought extinct until 1981. That’s when a ranch dog in Meeteetse, Wyoming, trotted home with one in its mouth, happy but ignorant of the significance of its catch. An ambitious captive breeding program has boosted their numbers. And yet, while recovering ferret colonies today can be found in Badlands and Wind Cave national parks in South Dakota, the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation and the UL Bend National Wildlife Refuge in Montana, and more than a dozen other locations in the Plains states, they remain endangered as a species.

The examples of negatively affected species go on. The US Fish and Wildlife Service considers swift fox populations to be ample, but their natural habitat on the Plains has been cut by about 60 percent due to growth of the human footprint.35 Also struggling to survive against this loss of room is another Great Plains native, the mountain plover. The transformation of grasslands into industrial agricultural plots and asphalt rectangles surrounding big box stores has plovers heading toward threatened species status, something their East Coast and Great Lakes relatives already have. These diminutive birds are known to some as “prairie ghosts,” as their dusky coloration helps them blend almost seamlessly into the landscape. The name could be prophetic if their habitat continues to shrink.

As land has gone into agricultural production, or been cleared for other development, non-native bird species in the Plains have increased in number as the native vegetation that many species evolved with has been lost. Ring-necked pheasants, gray partridges, and house sparrows are among the invasive species competing with native species.36 But if we could give bison a larger slice of the public landscape, some of these other species just might expand, as well. Because bison utilize the landscape differently than cattle—moving more often, not lingering around water sources, favoring a different vegetative menu—native vegetation would gain an ally against invasive species, riparian areas wouldn’t be so trampled, and the prairie not so heavily grazed. Wildfires, more likely in a warmer, drier climate, might not be as destructive on the Plains thanks to the vegetative patchwork left by bison.

Though the Great Plains is defined by prairie and sometimes referred to as the Great American Desert, it is an arid but not a waterless region. The Missouri and Platte rivers and their tributaries funnel snowmelt through the Plains. For early nineteenth-century explorers, these rivers provided access to the unknown West as they traveled by canoe, keelboat, and pirogue. These waters also provided the explorers’ larder, as lakes, oxbows, and kettle ponds lured deer, elk, and bison, as well as mallards, pintails, teal, and Canada geese, among other species. Beavers were the engineers of the water world of the Plains. Their dams affected water flows, created ponds that in turn became lush riparian areas, and even “managed” woodlands to a certain extent by chewing downing trees.

Considering their size, horns, demeanor, and long, indomitable presence on the continent, it’s understandable that bison for so long have been held in esteem. We marvel at their long history, how their very being exudes the concept of wildness in today’s over-populated and developed world, their encapsulation of raw power. They appeared on the back of the Indian Head nickel that was minted from 1913 to 1938, became a symbol of the Interior Department in 1917, and have been part of the National Park Service arrowhead emblem since 1952 because of bison’s reflection of conservation. They were designated the national mammal of the United States in May 2016. But admiration for bison goes much further back. They played a key role in nourishing civilizations, literally and figuratively. For more than ten thousand years they were a veritable cupboard for Paleo-Indians, Native Americans, and settlers, providing food, clothing, and shelter. At day’s end, Native Americans would return to tepees made with bison hides, use bison robes as insulating carpets and as blankets, and cook meals in massive bison stomachs. They and mountain men alike would use bison sinews for thread; turn horns into goblets, powder horns, and ladles; and reduce hooves through boiling into glue for attaching arrow points to shafts. Bison fur—fine, insulating hairs close to the body covered by more coarse outer hairs that provided a layer of protection against rain and snow—filled pillows, was woven into ropes, and adorned headdresses. For some, it even found new life as human hairpieces.37 The coarser outer hairs also were used to fashion horse halters. Not overlooked were bison tails, which became fly swatters.38 Portions of hide served as saddle blankets, were fashioned into moccasins as well as drums, and used as palettes. Bison brains tanned these hides, while hearts became pouches. The animals’ manure, plopped down as patties on the prairie, when dried became fuel for fires when wood was not available.

Meat was not just a given, it was survival and a daily meal for many native cultures.39 That which wasn’t to be eaten promptly had to be cured, and that meant hours carving thin strips from the carcasses to hang in the sun. This work was done by the women, who also spent hours fashioning tools and utensils from bison bones, and more time adding artistic flare to both clothing and tepees.40 Sections of the hide were fashioned into “parfleches,” early storage trunks. In North Dakota, I gazed at one of these handsomely decorated bags that was hanging from the roof of an earth lodge at Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site. Geometric designs painted in vivid reds, blues, oranges, and whites covered the hide. These nineteenth-century suitcases safely stored clothes, dried foods, and trade items. In an effort to keep the parfleches safe from rodents and any rain that might leak through the lodge ceiling, rawhide swatches were threaded onto the cord that suspended the bags.41 Two centuries ago, George Catlin saw parfleches and more in person. Raised in the heart of New York State on the family farm, he set out in life to follow in the footsteps of his father, a successful attorney. But his passion to paint prompted Catlin to shelve his law books and take up brush and palette with a studio in Philadelphia. Though he initially concentrated on small portraits, one day he was awestruck by a delegation of Native Americans that passed through Philadelphia on their way to Washington, DC.

He recalled this incident in Letters and Notes on the North American Indians:

A delegation of some ten or fifteen noble and dignified-looking Indians, from the wilds of the ‘Far West,’ suddenly arrived in the city, arrayed in all their classic beauty—with shield and helmet—with tunic and manteau—tinted and tasseled off, exactly for the painter’s palette. In silent and stoic dignity, these lords of the forest strutted about the city for a few days, wrapped in their pictorial robes, with their brows plumed with the quills of the war-eagle.… Man, in the simplicity and loftiness of his nature, unrestrained and unfettered by disguises of art, is surely the most beautiful model for the painter—and the country from which he hails is unquestionably the best study or school of the arts in the world … and the history and customs of such a people, preserved by pictorial illustrations, are themes worthy the lifetime of one man, and nothing short of the loss of my life shall prevent me from visiting their country, and becoming their historian.

Catlin let go of miniatures and instead worked on detailing the history of Native Americans by traveling the West.

From 1832 to ’37 Catlin made forays into the West and Midwest, visiting dozens of tribes to record their lives on canvas. He spent time with the Blackfoot, Crow, Cree, Sioux, Mandan, Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, Osage, Chippewa, Sauk, and Fox. The artist produced more than three hundred portraits during his journeys, as well as a couple hundred related paintings. He marveled at the native languages, noting at one point that the Crow and Blackfeet speak completely different languages, that the Dakotas have a different language than the Mandans. His portraits of two Mandan chiefs on the Upper Missouri so impressed the chiefs that they named Catlin Teh-o-pe-nee Wash-ee, or medicine white man. Catlin’s words and paintings captured the Great Plains in its pre-development rawness and magnificence before settlers swept over it.

“In looking back from this bluff, towards the West, there is, to an almost boundless extent, one of the most beautiful scenes imaginable,” he wrote in 1832 as he gazed out from the Lower Missouri River. “The surface of the country is gracefully and slightly undulating, like the swells of the retiring ocean after a heavy storm. And everywhere covered with a beautiful green turf, and with occasional patches and clusters of trees.”

You can find such settings in some places today, but very few with bison on them.