Читать книгу Re-Bisoning the West - Kurt Repanshek - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

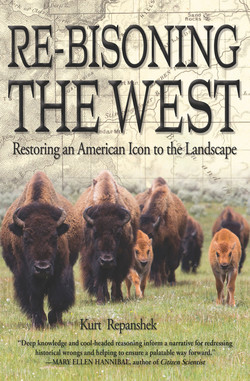

Avast, placid sea undulates slightly, as though to the rise and fall of the tide, staining the ground in all directions to the horizon. Though this sea contains no water, it moves in unison, rippling up and down, forging ever forward: herds of bison covering the landscape. Their dark brown shaggy humps rise not with a tide, but with the rolling hills. A dust cloud billows in their wake. Their baritone grunts, swelling and ebbing with the herd, carry across the Great Plains.

Late September nights in the backcountry of Yellowstone don’t hold warmth. They grow cold quickly. We had a reasonable pile of broken branches to feed the flames of our campfire until night called and we’d crawl into the down bags waiting inside our tent. Flickering shadows danced skyward against the lodgepole pine canopy, and an ebbing glow from the campfire leapt out across the forest floor. The snap and crackle of the fire was occasionally interrupted by nearby Lone Star Geyser as it fumed and sputtered and loosed a steaming whoosh of hot water, sending rivulets gurgling down to the Firehole River.

Though not our first backpacking trek through the park, we still had understandably nervous thoughts of grizzlies clacking teeth in the middle of the night, their low but unmistakable growl filling our ears. What we didn’t count on was the bison. Here in the forest. As the animal ambled along the firelight’s periphery, we couldn’t tell in the fading twilight if it was a bull or a cow. But at a weight north of one thousand pounds, male or female, it didn’t matter. It could inflict broken bones and trample our tent just by turning around. Nudging more wood into the flames, we watched the bison linger along the rim of firelight and then settle to the ground for the night.

Bison are deceptive. They are ponderous in their bulk, and their expressionless demeanor lends a certain stolidness. Matriarchal in herd structure, they are quick to defend their young, always conscious of nearby predators. They also are surprisingly nimble, capable of turning quickly and accelerating to forty mph. Bison are a mammalian relic from deep out of the past that are amazing to watch as they move in herds across the landscape or simply hunker down to bask in the sun while their calves frolic. They are powerful creatures, physically and iconically. Wander into an art gallery in the West and odds are good you’ll find images of bison staring out from canvases. Potent images of stout, indomitable animals that are hard to turn your eyes from. They are portrayed as they stand on the landscape, and at times in surrealistic, neon hues as the artist strives to depict their spirituality.

Back in 2007, the folks in West Yellowstone, Montana, no doubt recognizing the representation of wildness and strength in bison, staged a “Where the Painted Buffalo Roam” fundraiser for their town. This campaign featured twenty-six three-quarter-sized fiberglass cow bison statues painted by select artists to reflect themes from Yellowstone and Native American people from the region. These bison stood in various public places around town for a period of months, and then were auctioned off. The paintings on the bison statues were wide-ranging. One depicted the park’s Upper Geyser Basin in full steam mode, another feral horses at full gallop, another, the artist noted, “an attempt to portray part of the North Plains Indian belief in the legend of the Sacred White Buffalo Calf Woman, who came down from the heavens long ago to show the people the way to the sacred path.” The highest bid, of $17,000, went for a bison painted on one side to show turn-of-the-century tourists exploring Yellowstone by tally-ho coaches, and on the other a scene of yellow touring buses. The project raised $161,500. Cattle canvases would not have fared as well.

That night in the backcountry of Yellowstone, the animal that shared our campsite was an ancient animal, figuratively. The Bison genus stretches back some two million years to Asia. Somehow, through all the ice ages and despite all the long-toothed predators, it never went extinct. It probably should have, at least once or twice, as did the camels, mammoths, and ground sloths. Bison somewhat recently arrived in North America, about two hundred thousand years ago during glacial periods that dropped sea levels and allowed a land bridge to surface and connect Asia to the land we know today as Alaska. By crossing the thousand-mile-long strip known as Beringia, which now has been underwater for about twenty thousand years, the animals reached a new continent with near-endless possibilities for their kind.

The bison in Yellowstone’s Hayden Valley really don’t look much different from those who made the crossing. Oh, they are smaller, their horns closer to their skulls, their bodies more compact. We know this thanks to Walter and Ruth Roman. The couple literally scraped, or, more precisely, blasted, a living from the land with their Lucky Seven Mining Co. Summer into early fall 1979 found the Romans at their placer mine along Pearl Creek above the Chatanika River, sixteen miles northeast of Fairbanks, Alaska.1 Their tool of choice was a pressurized hose that spit out a nearly six-inch-wide torrent of water that could cut through the permafrost and, hopefully, expose gold-bearing rubble. This particular form of mining, known as “hydraulicking,” dates to the Roman Empire. Those Romans didn’t know everything, though, and miners during the California Gold Rush of the 1850s greatly improved the technology by adding a nozzle to create a more forceful jet of water to tear into hillsides.

What the modern-day Romans found as they slowly eroded the hillside into muddy torrents was not gold, but not entirely invaluable, either.2 Under their watchful eyes, the powerful sluice of water raked back and forth and back across the slope, thawing, chewing, gashing, slashing, and washing away a slurry of sediments, pulling away rocks and soil and debris from the past thirty-six thousand years. No gold fell away, but mired in the muck were the hindquarters of a prehistoric creature jutting out like some massive tree trunk. With a tail. Dubbed “Blue Babe,” in part for the color of the long-buried carcass, this steppe bison (Bison priscus), as paleontologists would later conclude, must have been a magnificent animal when breath filled its lungs, blood flowed through its veins, and rippled muscles flexed its hide as it walked. Blue Babe stood almost seven feet tall at the shoulder, weighed a ton or so, and had crescent-shaped horns ranging more than three feet from tip to tip. Those horns weren’t for show, not at all, but for defense, for survival. Driven forward by two thousand pounds of bone and brawn and fury, they could be particularly effective. The animal’s size and strength enabled it to endure on the mammoth steppe during the Pleistocene. It was a cold, somewhat arid place, covered with grasslands that wandered across the landscape then as they do today across the Great Plains of the United States and southern Canada. Forbs—herbaceous flowering plants—grasses, and perhaps willow shrubs provided the forage the great beast consumed and, in turn, transformed into muscle.

Blue Babe grazed this landscape with other bison, of course, but also with woolly mammoths, musk oxen, and horses. As they all fell into the category of prey for the carnivores of the day, they needed to keep watch for packs of dire wolves, short-faced bears, and American lions. The lions were among the big apex predators on the Pleistocene landscape, much larger than their relatives of today, though lacking the manes of African lions. The males that preyed on the likes of Blue Babe weighed more than 900 pounds, and possibly as many as 1,100 pounds.3 Females were smaller by a few hundred pounds, but, like wolves today, their tendency to hunt in small groups enabled them to overwhelm their prey from all sides and tilt the battle in their favor. They’d stalk, feint, and charge, take swipes and bites, always searching for a weakness, for an opening to launch a fatal attack. The steppe bison had no chance. Blue Babe’s death was, in the end, inevitable.

In that battle thirty-six thousand years ago, the bull bison was attacked from behind, either caught by surprise or run down by a lion, or lions, in flight. Claws raked its flanks, teeth pierced the thick hide that bore scars from past battles survived. Though the bison outweighed the lion by at least half a ton and had those massive horns, it nevertheless was at a marked disadvantage. Stumbling to the ground was fatal, as the predator tore at the bison’s girth, determined to rip through the leathery hide to reach the muscle and organs shielded by the rib cage. The battle attracted scavengers, who patiently waited their turn. But was that how it played out? Was it that cut and dried, a fierce attack accomplished in a matter of minutes? That was the mystery that landed at the muddy feet of R. Dale Guthrie. Born in 1936 in Nebo, Illinois, a village of fewer than five hundred then and less now, he was educated in paleontology at the University of Chicago and went on to teach zoology and Arctic biology at the University of Alaska from 1962–96. Though arguably best known for a book he wrote on Blue Babe, Guthrie traveled extensively in the Arctic and to Europe and Asia to study and decipher prehistoric sites. His avocation, second to paleobiologist, was art lover. He especially enjoyed studying Paleolithic art and searching for connections to, or representations of, Pleistocene natural history. With no time machine to transport himself back to that epoch, what better way to understand its wildlife than through the art the hunters left behind? Guthrie came away from a 1979 conference in Switzerland determined to try “to place Paleolithic art in a larger dimension of natural history and [link] artistic behavior to our evolutionary past.”4 Among the professional papers that flowed from Guthrie’s travels was one in which he wondered why the artists were drawn to create images of animals we refer to today as charismatic megafauna, the great beasts of their day thousands of years ago. Did the pinstriped horses and polka-dotted reindeer these people painted actually trot across the landscape, or were they embellished creatures the artists held in esteem? Why did so many scenes depict hunting?

In July 1979, when the Romans called Guthrie, the paleontological puzzle confronting him, quite ignominiously, was protruding butt-first from the hillside. Guthrie, assisted by his wife, Mary Lee, and son, Owen, walked up to the muddy, well-preserved but slightly frozen bison rump and was immediately struck by the smell, “a rich, pungent rottenness, like nothing else I have smelled.”

“It was a rottenness aged for millennia in the frost—not a stench, but a sweet, intense tang,” he recalled.

The source of that stench was thawing quickly, too quickly to study from its awkward resting place. When the rear half of the bison began to tear away from the front end that was still securely frozen in place, Guthrie arranged to have it carted off to the University of Alaska and the Institute of Arctic Biology. Once there, it was put in cold storage in a walk-in freezer. When the animal’s head and shoulders melted free, they too went into deep freeze there. During an ensuing necropsy, the equivalent of a human autopsy, on the stunningly complete remains, Guthrie pieced together a theory for how Blue Babe died. And it wasn’t what most of us would think. His conclusion did not support a quick death by a pride of lions that had little trouble tearing into the animal. This bull had dense neck muscles covered by thick, sheet-like layers of skin. They formed a tough physiological laminate that a lion couldn’t easily clamp its jaws around. As a result, the cats would resort to smothering their prey. And that’s what Guthrie figured had happened.

“Using claws for a secure hold, a lion will throw a buffalo down and clamp the buffalo’s entire nose and mouth in a firm bite or clamp the trachea closed,”5 he explained. With Blue Babe, the paleobiologist based his theory on puncture wounds coupled with stains left by blood clots that had formed around the bull’s snout. But there was a twist in this case, which was unusual from the start. Why wasn’t the carcass devoured? Guthrie theorized that fewer than three lions were involved in attacking the bison, and that the carcass froze solid before they could consume much of it. Lending credence to that theory was that a tooth fragment from one of the predators, possibly broken off as the lion tried to tear through the frozen hide, was later found in Babe’s neck by a taxidermist.6

Because so much of the carcass was intact for the Romans to jet wash out of the hillside, Guthrie surmised that Blue Babe died early in winter. Bitterly cold temperatures turned the bison’s skin into a sheet-metal-like barrier that no predator could penetrate.7 Then, before spring thaw could arrive with warming temperatures that would soften the skin, bloat the carcass, and spew the odors that would bring the predators and scavengers back, Blue Babe was buried by sediments. Perhaps they came in one large swoosh of a muddy torrent unleashed by snowmelt. Or perhaps there was an avalanche that sent snow and soil down atop the carcass. And then some more layers were added for good measure, and they, in turn, froze. This process, repeated again and again, cemented the bison’s remains in permafrost, out of reach of predators and scavengers and out of sight for tens of thousands of years until the Romans came along with their powerful hose in search of gold.

The preservation of the find, the seeming freshness of it, Guthrie later told a gathering at the thirty-second Alaska Science Conference in 1981, was simply amazing. And, no doubt surprisingly to most of us, appealing in a gastronomical context.

“Red meat in the mud. It is really a dramatic thing to all of a sudden fall into your lap, to see this coming out—an animal that no longer exists, with black hair, wool, and fat,”8 he told his spellbound audience. While the remaining flesh might not have looked butcher-shop fresh, even after thirty-six thousand or more years it didn’t look too far gone to sample. So one evening in 1984 Guthrie invited the taxidermist who was able to showcase Blue Babe in repose for the university’s museum and some friends for bowls of Blue Babe stew. “The meat was well aged but still a little tough, and it gave the stew a strong Pleistocene aroma, but nobody there would have dared to miss it,” said the paleontologist.

The bison’s nickname, “Blue Babe,” was derived from both the mythical, oversized ox that accompanied the legendary lumberjack Paul Bunyan of American folklore9 and from the bluish hue left on the bison’s skin due to a chemical reaction between minerals in the surrounding soil, phosphorous from the skin, and the air. Babe was just one of the ancestors of today’s Bison bison. Coexisting with the bull for a time, but eventually succeeding it, was the Ice Age Bison latifrons, or long-horned bison, a massive beast at more than eight feet tall and more than two tons on the hoof. It shared the landscape for about one hundred thousand years with Bison antiquus. Then arrived Bison occidentalis for a somewhat short period and, finally, today’s Bison bison.10

Collectively, the various subspecies demonstrate how, down through the millennia, the populations of these now iconic animals rose and fell and evolved, facing climate change and enduring predation by four-, and later two-, legged carnivores. Their numbers and physiques altered to suit the times, standing large and massive when the climate produced mild seasons of plentiful vegetation, and shrinking smaller and less hulking during glacial periods when forage was comparatively scarce and a smaller body size better maintained core temperature. No other land-based megafauna have endured through the ages as have bison. They are hard not to admire, not just for their appearance but also their perseverance and uncanny adaptability.

Early man venerated bison much as we do today, probably to a greater degree, because the animals provided food, shelter, and warmth. When Blue Babe was being attacked by that lion, or lions, on the other side of the world in Europe humans were accustomed to blocking the cold of winter with the heavy robes of bison and other furry ungulates and nourishing themselves with the equivalent of bison ribeyes.11 Paintings adorning the walls of caves at Altamira, Spain, portray bold, handsome bison. Many of those sprawling images, some of which are life-size, were crafted in life-mimicking pigments.12 These were not mere stick figures, not doodles to pass the time until the rain stopped. These were meant to show respect, even awe. Ochre, hematite, and manganese were used alone, or diluted or mixed with other substances, to produce varying shades of skin tones. These Stone Age artists put much thought into the images they wanted to create with the color palette and canvas at their disposal. If the image alone didn’t reflect enough respect for the animals, it was further enhanced and given lifelike qualities by the artist’s use of rippling rock wall contours to add heft, some muscular definition, to the paintings.

That idolization of, and reliance upon, bison came to North America with those humans who walked from Asia east to the continent. As in the old world, in the new one the beasts were hunted for food and shelter, clothing and fuel, even ornamentation. Evolving societies of native cultures were nothing if not inventive and practiced at finding what they needed. Bison hides were scraped clean of fat and muscle to become tepees and robes. They were stretched over curved tree limbs to form bull boats that could be paddled across a river. Bison ribs became runners for winter sleds, while sinews launched arrows from bows or served as thread. And, of course, the meat was about the richest protein around.

But bison were more than sustenance and shelter. Great Plains people viewed them almost as deities, and perhaps rightfully so, considering not only their sheer bulk and demeanor but also the reliance on them and their cultural significance. Bison were mythical, practical, spiritual, and transformative animals. Black Elk held bison in particular regard. Born shortly before the end of the Civil War, this Oglala Sioux holy man fell sick when he was nine years old and lingered for several days in a semiconscious state. During that period, he had a vision in which he was taken to the center of the Lakota world and instructed on the keys of earthly unity. “I was seeing in a sacred manner the shapes of all things in the spirit, and the shape of all shapes as they must live together like one being,” he recalled.13

As a young man, Black Elk traveled for a while as part of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, though he would later return to the Black Hills of South Dakota and Wyoming to describe for whites the traditions of the Lakota. In 1932, with his son acting as translator, Black Elk related his life story to a biographer. During hours of interviews, Black Elk explained the Lakota’s reverence for bison. “The buffalo represents the people and the universe and should always be treated with respect, for was he not here before the two-legged peoples, and is he not generous in that he gives us our home and our food?” he asked rhetorically. “The buffalo is wise in many things, and, thus, we should learn from him and should always be as a relative with him.”14

But human predators, primarily those with white skin, didn’t always share that respect. Hunters hired by the railroads to provide meat for the gritty crews building the Transcontinental Railroad, military personnel working to deprive the native peoples of their foremost sustenance, and buffalo hunters making a living by selling bison robes and hides decimated the species in the nineteenth century, pushing it toward extinction. So great and widespread were the killing fields that a Paiute medicine man, Wovoka, near the end of the century instructed his people to perform a once-forgotten dance that he maintained would drive the whites from the landscape.

Wovoka had been born in Nevada, about seven years before Black Elk. Though his teenage years were spent living with a white family, a time during which he learned about Christianity, when he was about thirty years old he refocused on Paiute traditions and beliefs. A powerful vision he experienced during the total solar eclipse of January 1, 1889, spurred Wovoka to revive the Ghost Dance—which an earlier Paiute medicine man, or healer, had started in 1869. That man, Hawthorne Wodziwob, encouraged his followers to perform a circle dance. A series of visions convinced him that doing so would wipe the white people from the earth while native cultures would be left to prosper. Wovoka built on this message through his own vision, and promoted it as a way to cleanse the world of whites and renew the landscape and its wildlife, including bison. “All Indians must dance, everywhere, keep on dancing,” urged Wovoka. “Pretty soon in next spring Great Spirit come. He bring back all game of every kind. The game be thick everywhere. All dead Indians come back and live again. They all be strong just like young men, be young again.”15

But the return of bison was not spawned by these visions or Ghost Dance rituals. Late nineteenth-century technological advances gave buffalo hunters even more reason to kill bison. These advances seemed ready to doom both the species and the native peoples who relied upon it. As more and more bison were killed, the people who once followed the great herds through the seasons continued to lose hold of the Great Plains as their homeland and were being pushed into reservation life. The downfall of bison herds was dynamic, though not accomplished solely by two-legged white predators. Other factors included the hunting by native cultures and even predation by wolves and grizzlies. Some think disease may also have played a role. Myriad factors contributed to the Great Slaughter.

Bison miraculously did come back, but not due to a prophecy. Their future was ensured by a handful of players, of white and native cultures, who sensed the demise of the great animals and worked to prevent it. There were men whose names stand out in American history, as well as some who have been overlooked. Among those often relegated to the back of the story are several men with Native American blood, including two who built a turn-of-the-century herd of several hundred bison that today is key to the return of purebred bison to the Rocky Mountain Front that sidles up to Glacier National Park. Still, it was a modest number of players, a small, far-flung group in a sparsely populated, far-stretching nation at the turn of the twentieth century, that crossed paths and collaborated as they worked to preserve bison. Today we see their success in small but strikingly rich, diverse pools of bison genes nurtured from Canada to Mexico, from Iowa to California. These men had no template to work from, no previous conservation mission or map that they were trying to emulate. There were no instructions, no how-to manuals. They were acting upon their own instincts, developing their own theories, arguing when necessary to gain some forward momentum in securing a place in the country where bison could survive.

Their timing coincided with a national consciousness welling up around the conservation of wildlife and natural spaces. John Muir had been praising the values of nature in promoting the High Sierra and what would become Yosemite National Park. His efforts corresponded with the rise in the 1870s of magazines such as American Sportsman, Forest and Stream, and American Angler that cultivated national audiences concerned about wildlife. Emerging at the same time were various organizations dedicated to wildlife and conservation, groups such as the League of American Sportsmen, the Camp Fire Club, and the Audubon Society.16

Four of the actors who had key roles in engineering the recovery of bison had big, oversized personalities; they were proud of their accomplishments, and not shy about announcing them. Each had hunted bison. Yet each came to recognize the dark fate bison faced, and was determined to see the animals avoid it. To a large degree they succeeded, as bison numbers rebounded from dozens to hundreds to thousands and then tens and even hundreds of thousands. Not to the millions that once roamed the West, but to herds that today ostensibly will prevent the species from vanishing.

But while the numbers are impressive, the touted recovery of bison as a unique, genetically pure species is not that simple and not so certain. Arguments have been made over whether the species is indeed recovered, saved from extinction, and some courts have entertained those arguments. At the moment, there doesn’t seem to be any great urgency to resolving them, thanks to an estimated half-million bison in North America. Those animals are divided into two groups: commercial herds, raised for meat, their decorative hides, and even their heads as Western chic mounts on display in homes, hotels, and lodges; and conservation herds, which are viewed as inviolate reservoirs of pure bison genes intended to preserve the species. Media mogul and philanthropist Ted Turner owns the largest commercial bison herd, some fifty-one thousand head,17 while conservation herds are scattered across the West and the Great Plains states, most often in units of the National Park System but also in preserves such as those managed by the Nature Conservancy and on Native American reservations.

Conservation herds stretch from Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park in the Northwest Territories south to Yellowstone, and from California to Iowa. State parks from Florida to Utah and even “landscape zoos”—with enclosures of tens of acres—in California feature bison. The National Bison Association, a non-profit organization that promotes commercial bison operations, has a goal of seeing bison numbers reach one million, possibly as soon as 2025. And yet, the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources lists bison as near threatened. Many scientists accept that the plains bison is an ecological relic, one effectively extinct within its historic range.18 There are scant few bison roaming wild as they did 150 years ago, and the bulk of bison in North America are in commercial herds often managed to a degree as if they were cattle. Some of these captive bison face selective breeding, are moved through rotational pastures depending on the season, and are provided veterinary care on occasion. Altogether, that approach to managing bison threatens to move them away from their Bison bison ancestors both physiologically and behaviorally. At the same time, suitable land for bison is disappearing quickly. Two-and-a-half-million acres of shortgrass prairie were lost to agriculture between 2015 and 2016.19 Another 1.7 million acres were transformed in 2017.

The species’ future depends on our best animal husbandry, for both commercial and conservation herds. Without dinner-table appeal for bison ribeye steaks, tenderloins, and tri-tips and the desire to mount their heads over fireplaces in trophy homes, there would be little incentive to ranch bison. Were it not for the Interior Department’s determination to preserve bison as genetically pure, or as pure as possible, and the resolve by native peoples to connect with their spiritual past, the number of conservation herds very possibly would struggle to grow in number with healthy genetic diversity.

Compounding the threat of genetic pollution and pocket conservation herds is the reality that bison have been removed from all but a sliver of the Great Plains. Bison in large numbers don’t seem to mesh with our societal explosion of cities and towns, industrial zones, agricultural conglomerates, and even ranchettes. Without room to roam, conservation herds are limited in number of both herds and individuals. The removal of bison from the landscape also has affected the region’s ecosystems by disrupting natural processes that other native species thrive in and rely upon. The cascading ecological impacts are clearly visible, both in terms of fauna and flora. As bison go, so, too, go a number of other species that evolved alongside these cloven-hoofed creatures and which also have been slowly squeezed by development that turned the Plains into suburbia and conglomerate agricultural tracts. Swift fox, black-footed ferrets, and greater sage-grouse all face precarious futures without society’s intervention.

There are reasons for optimism. After all, bison have great public appeal. Tatanka, the Lakota word for buffalo, entered into popular lexicon in 1990 via the Oscar-winning movie Dances with Wolves. The designation of bison as the national mammal in 2016, along with the arrival of ground bison and bison steaks in groceries, raised the visibility of an animal that once was more numerous than any other ungulate on the North American landscape. The federal government’s efforts to see bison as a pure species remain on the landscape is a huge plus in their favor. But now, little more than a century after efforts to preserve bison began, the species faces a puzzling legal and biological predicament. Though sheer population numbers early in the twenty-first century placed an estimated five hundred thousand plains bison in North America, 96 percent of those animals are in commercial herds and lack genetic purity due to century-ago experiments to blend bison and cattle into some sort of super-livestock. Those experiments were conducted, ironically, by some of those who also worked so very hard to preserve the pureblood species. Today some conservationists argue the species, in a genetically sound form, needs the protection of the Endangered Species Act to survive. Some scientists view that as hubris, a grand measure of hyperbole. If a bison is 99 percent pure, containing just 1 percent cattle genes, does that weaken the species? That debate can, and will, continue without immediately dooming bison. But society must be willing to allow bison to recoup some of the landscapes they’ve been removed from if we want the species to succeed. There is a large amount of shortgrass and tallgrass prairie lands outside the National Park System that, in theory at least, could be opened to bison. Native peoples have nearly one hundred million additional acres on their reservations that could help support the animals. More acreage could be found on public lands held by states and the federal government. The era of large-scale conservation does not have to be a vestige of history or victim of development. We just need to be more creative and willing to forge alliances that would benefit from wild bison. In turn, bison would benefit the landscape, as it has been demonstrated that they are ecologically better than cattle or sheep. Bison are icons not just of the West but of the entire country. They are cultural centerpieces and are seen as key to lifting up native peoples spiritually, economically, and in terms of longevity. They should be given the opportunity to thrive not as open-air zoo specimens but as ecologically functioning biological engineers on the land.

Those sentiments are shared half a world away. In Romania, in the Southern Carpathian Mountains, European bison, or wisent, vanished from the landscape two centuries ago. But work is underway to release at least one hundred of the species by the end of 2020. Those pushing the initiative point to many of the same reasons for their recovery operation: European bison create a mosaic landscape with their grazing, which in turn benefits biodiversity. Part of the region targeted for wisent encompasses the Tarcu Mountains, which are a component of one of Europe’s last significant wilderness areas. Successful recovery of the species would not only be an environmental victory, but is seen as a way to benefit the region economically, as well.20