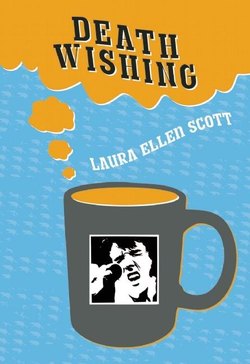

Читать книгу Death Wishing - Laura Ellen Scott - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5.

Yielding to pressure from an oppositional Congress and his own nagging curiosity, the President commissioned a blue ribbon committee charged with leading an open, national discussion of the opportunities and consequences of the Death Wish phenomenon. Populated by fifteen well-known thinkers, the committee members ranged from scientists to religious leaders to television actors, all of whom seemed to possess a certain photogenic moral certainty. The term “open discussion” meant that our celebrity representatives would hash things out on TV while we watched from the comfort of our homes. The discussion was heavily scripted, with the Dalai Llama yielding to Martin Sheen on the topic of the “resilient spirit of humanity,” while Steven Pinker asked leading questions of Oprah Winfrey. It was a ludicrous pageant of platitudes and vague reassurances, but the forum was enormously popular, and in no time the United States government had a hit reality show on their hands: The Wish Tank.

In a shadowed, starkly furnished setting reminiscent of an old PBS chat show or a post-modern play, Neil deGrasse Tyson and co-host Francis Bean Cobain reviewed the latest documented death wishes and tried to make sense of it all while the panel cooked up predictions and recommendations for future wishes. Four episodes aired over the span of six weeks before any of the panelists dared to bring up the subject of death, itself.

Cal Ripken: “So there is real pleasure in knowing. And knowing becomes its own experience.”

Amy Carter: “Yes, obliterating fear. We are all futurists now.”

Applause.

Sunday morning, bright and early. Wish Tank knocked the stuffing out of Meet the Press or any of those talking head shows. Val flicked it on and wandered away to another corner of the house, leaving it to blare in an empty room. We were getting ready to attend the Wish Local rally at St. Aloysius. Fresh from the tub and naked, I stepped on the scale in my bathroom. It seemed I was a pound lighter than last week, despite the binge of the night before. As if proud of me, Heidi Klum’s distant chirrup confirmed, “Well that’s completely awesome.”

I scrambled, mostly naked and mostly wet, to my room and shut the door, reducing the Wish Tank repartee to unintelligible vibrations transmitted to the soles of my feet via the ancient hardwood floor. I dressed in pale khakis and a short sleeved bowling shirt—my Sunday best, to be honest. Most of the clothing in my closet was, at this point, either too big or too small. I had landed squarely in the buffoon range of my wardrobe, and everything that fit me was best accessorized with a can of beer. I almost put on a pair of deck shoes before I realized I might be taking things too far. I caught sight of myself in the bedroom mirror and noticed that I resembled a down on his luck homicide detective. As I retrieved my loafers from the hallway, I heard Ms. Klum say, “And apocalyptics? Where do they stand?” Steve Ballmer had a quick, sweaty answer to this, but I didn’t quite catch it.

“Dad,” said Val. “Let’s go. This is bullshit.” He said this from the kitchen as he fussed over the coffee urn. Was I dreaming or did the boy sound almost enthusiastic? I detected familiar music and put my hand up in the justaminute signal, and dashed—as dashingly as a man of my size can dash—into the living room.

“Val, come here.”

A commercial for my weight loss program was on, with the usual thumpy techno pop and a bevy of plump ladies dancing around as if nothing was more blissful than self denial.

“What?”

“Just wait for it.”

Val slumped against the doorway and watched with me. Glistening plates of unlikely food, horse back riding, more dancing, huge pieces of chiffon catching the wind.

“There!”

Vibrant aqua script splashed across a white screen: The Freedom Plan. A beat before a husky female voiceover announced, “Now at last. The Freedom Plan.” And a beautiful, large, blonde woman dressed in a flowing white muslin suit emerged from the background, strutting seductively towards the camera. It wasn’t until she was quite close that one noticed the lit cigarette in her hand. Then a final image, as triumphant music swelled to a flourish: she took a long drag off the smoke and her eyes fuzzed in orgasmic satisfaction. “Real freedom,” the voiceover groaned.

Now Val was paying attention. “Did she just—?”

“Smoking is back, my boy.” Early that morning I’d groggily logged onto my online diet diary provided by the program, and there it was: in addition to my food fractions, water count, and exercise tally, I now had a field in which to enter cigarettes. “I’m allowed eight per day, as a matter of fact.”

Val ran his fingers through his lank hair and chuckled. “Cancer goes away and Big Tobacco comes back. Shit. Wish I’d thought of that.”

I decided to take the high road. “Well I’m not going to smoke. It’s filthy.” I straightened my shirt and changed the subject. “I suppose this is too casual to wear to the church?”

Val shook his head no. “No one gets dressed for church any more except hat ladies. You’re okay.”

We took a trolley and then hiked to St. Aloysius which is located in one of the least lovely, unreconstructed areas of West Side. The church steps were crowded with families exchanging goodbyes and making plans to meet up for late day dinners. But then I spotted Pebbles, seated on the steps, her arms wrapped around her rosy knees. She was wearing a dress, some light yellow cotton tube, but it was a dress. And she’d pinned a square of lace on top of her shiny red hair. A sweet gesture to propriety, but the frock was too short, and my eyes wandered over her brilliant white thighs. I think she noticed my attention, because she squirmed slightly and tucked in a little tighter.

She waved, looking lapsed and uncomfortable. Out of her element. She’d been waiting for quite some time.

St. Aloysius was a decrepit thing, had been even before Katrina, and was slated for demolition some ten years prior, but any structure that survived the Big K was suddenly a treasure. Even brutalist grammar schools from the seventies were subject to the preservationist urge.

I approached our girlfriend. Pebbles tried to smile but it came out crooked and strained. “They’re already loading in,” she said, nodding to a side entrance where a pair of ugly metal doors were propped open with a cinder block. I extended my hand and she took it, unfolding to her feet.

She flashed a quick smile at Val and looked away. Still stinging from last night.

Val stepped forward and patted her on the back. It was a weird thing for him to do, but she stood still for it, all the time staring hard at the church doors so as not to frighten him off. Like he was an autistic child. Or a deer.

I asked her, “What sort of crowd?”

“Scary. I think.”

As if to validate her impression, a trio of elderly women in tennis outfits strolled by. Two of them held hands, and they’d all bought their platinum wigs from the same cheap supplier. Sisters. Together forever. Next came a gentleman who appeared as if he’d stepped out of a cartoon OTB parlor. His checkered polyester suit was festooned with fabric pills, and he reeked of cigars. My enthusiasm plummeted. I was on the verge of suggesting we skip the event when an ivory town car took a reckless, squealing turn onto the street, rushed towards the front of St. Aloysius and lurched to a stop in front of its startled parishioners.

The vehicle was spotless with tinted windows and fresh new tires. When the driver emerged, he showed himself to be a caricature with blonde hair and golden skin under a black cap, sunglasses, jodhpurs, and boots. He flashed a grin for no one and everyone before taking a little nazi skip backwards to open the rear door for his passenger.

“Mirella?” said Val. “Now I’m impressed.”

Mirella emerged in her Sunday best, a knee length, lime green leather dress tailored so precisely it looked as if she’d simply hollowed out another woman and buttoned the husk up over her own. It was a threatening garment with a narrow collar and hem that cut into Mirella’s perfectly maintained skin. Mirella was one of those one-name-only individuals whose ethnicity was elusive; today she wore her thick black hair piled up on top of her head with a pretty Chinese stick run through it. Her eye shadow was the same shade of lime as her dress, but her heels were basic black, no less than six inches. Like weapons.

The most successful stripper-entertainer in New Orleans, Mirella was possibly sixty to eighty years old. Mirella might also have been a man. If not presently, then some time in the past. It didn’t seem to matter. She held our attention regardless, occupying a realm beyond sex; she was a creature of the fourth dimension, with better practices and more interesting options than any of us fools could imagine. Her driver man cupped her elbow to guide her to the church. The crowd made way, and she smiled like the queen she was. She and the driver ducked through the propped open metal doors, and I no longer had any doubts.

“Let’s get a decent seat,” I said.

Pebbles asked, “They just gonna leave that car in the street?”

“No one’s going to touch it.”

Within, rows of folding chairs were filling fast. This was a banquet room and not the church proper, windowless and dim, save for the furthermost row of ceiling lights illuminating a podium on a slim talent-show style stage. I could not imagine Queen Mirella resting her perfection on cold, gray metal, and indeed she was nowhere to be seen amongst the unwashed. Rather, she was arranged atop a stool set off to the side from the rest of us, where she was quite fortunately backlit by an emergency exit sign. Somehow she managed to draw the light forward like a stole around her shoulders. Her man stood behind her, all but invisible.

Mirella posed her long dark legs at an alluring angle, one knee a little higher than the other and both legs pressed close to each other in a hungry kiss, almost entwining at the ankles but not quite. All she needed now was a microphone and a sax player.

Oh, and one more detail. She smiled down at the rest of us like the God-damned Mona Lisa. I remembered something that I’d heard back when Death Wishing still lent itself to giddy gossip: that Mirella intended to OD and wish the sky orange. And now to be this close to her? The hairs rose up on my neck.

Val led us to seats at the front, but close to the exits. Eventually there were fifty of us in that stifling, dark room, most being unrepentant “characters” from the mid-low end of the economy. Not a normal workaday soul in the group. Of course since Katrina, everyone looked a little rough, a little raped, and even new-bought clothes tended to hang from the shoulders like government issue from an island nation you never heard of.

Enter Rollie, my queen-like weight loss leader. That is, before she got caught up in the Wish Local movement. Rollie was in her sixties, had kept her weight off for twenty four years. She was no nonsense, almost militaristic, and I missed her like hell. I’m sure her social views were gruesome, but her courage and knowledge of exotic fruit were impressive. She strolled in from a moldy antechamber wearing a sculpted periwinkle linen skirt suit, white stockings, and periwinkle flats dyed the exact shade of her outfit. I think there was even a slight periwinkle tint to her short white hair. I wouldn’t put it past her.

So Rollie in her breathtaking, ready-for-heaven ensemble, and Mirella in her assertive lime leather. The rest of us? Filthy monkeys.

And Rollie wore that same smile, Mirella’s smile. The women nodded to one another, and we all held our breath in the presence of such supreme collusion. Val’s appreciation was cool, but Pebbles gazed like a child in awe. She wanted to be one or both of these women when she grew up.

Rollie took the podium. No notes. No amplifying device, no power point set up. Someone closed the door and we were sealed in.

“Welcome,” she said. “Welcome, my family.”

Val made a face.

“We’ve gathered today to acknowledge the truth.”

“Amen,” called a voice from the shadows.

To which Rollie cautioned, “I do appreciate we’re in a church, but let’s not allow mystery and faith to confuse our mission. We have work to do.” Her remark provoked some uncomfortable shifting, and we looked to Mirella the way one might peer into a flight attendant’s face during turbulence. Mirella was solid, unmoved, eyes forward.

Rollie said, “You all know about the houses on Tennessee Street, right?”

And how could we not? Tennessee Street ran through one of those tragic Ninth Ward neighborhoods virtually erased by Katrina. Think of that famous photo of the two hundred foot barge squashing a school bus—that neighborhood. Used to be a street full of kids, old women and gangsta rap. Then for a while it was just wreckage, feral cats, and crickets. Have you ever seen a city street that was utterly dark at night, and silent? Because there is no electricity and there are no people? Of course you haven’t. No one ever had, until the storm.

“The Tennessee Street event marks the sixth documented wish to be implemented,” said Rollie. She took a breath. “In Southern Louisiana. The government will issue a report this week that will detail the demographics of enacted wishes, and one of the things that report is gonna say is that a disproportionate amount of wishes come from our area.”

That was newsworthy. We shifted, muttered amongst ourselves like worried hens. The Tennessee Street event occurred after one of the original residents brought in a pre-fab home to set it up on his old land and declared it time for the neighborhood to return. And it did, but not in the way that he expected. While it had taken him more than a year to reclaim and rebuild his home to a livable condition, his great aunt, who had lived on Tennessee since before the great white flight of the sixties, managed to rebuild the rest of the neighborhood overnight.

“Wish they was houses back on Tennessee Street,” she said, and then she went to sleep for the very last time. In the morning she was gone, but where every row house and shotgun shack had been swept away by the surge following the failure of the 17th Street Canal, now stood a perfect, if boring looking, Dan Ryan style modular home. All the plumbing plumbed, all the electricity wired, everything waiting for the city to do its part and flip the big switch that would restore basic services to the community.

It was an emotional thing to watch on the evening news, as the shreds of disintegrated families were led back to their homes under the protection of their nation, for once. Women cried, men cried, we all cried to see it. And we all waited for the administrative shoes to drop on those people’s heads, but that never really happened. There were tax issues to be ironed out, but in Louisiana government crawls at a snail’s pace. So here was a new, shiny neighborhood. Two strips of little putty colored, mushroom houses in the Lower Ninth Ward to form a sliver that looked a lot more like a Northern Virginia suburb than the cradle of jazz.

Rollie intoned, “No, we have no problem with God, but His intermediaries? We can’t count on them. Not priests, not government, not any appointee who was in place and failed us before. Do you remember waiting for help and charity? Do you remember how none of the structures of responsibility, from the levees to the ministries to the White House, were adequate after the storm? The only real help came from family, friends, and heroic neighbors. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not here to talk anarchy, I’m here to talk about local interest.”

I leaned forward in my seat. I wished I’d been able to convince Martine to come along.

“We have no science other than statistics to support the suggestion that Death Wishing favors our region. But the numbers are too important to ignore. We must take measures to ensure our own safety and, you bet I’m gonna go there—prosperity. This is no longer a question of believing or not believing in the phenomenon of Death Wishing. No one can live outside it any more.”

At this point Pebbles slipped her hand into mine, making me want to utter my own “Amen.”

What followed then was an impassioned but sometimes strained argument that the Wish Local movement was a deity free philosophy of opportunity, though the mystic subtext was undeniable. Rollie and Mirella came off as High Priestesses, even though they insisted they were merely community leaders. Back in the cheap seats of my mind, I knew they were just as prone to corruption and inefficiency as anyone else, but I didn’t care. I was thrilled to be part of the drama. Rollie was an artist, and it was a delight to watch her work the crowd, slowly releasing and cranking the tension until all rationality gave way to stomping, hooting, and other forms of sweaty affirmation.

My favorite part was the end. We were on our feet, and Rollie stepped back to accept our wild applause, her eyes wet with triumph. Then we turned our attention to Mirella. She had come down from her display to balance on those wicked heels, and the light that cradled her seemed to pulse and swell. We quieted down. She raised her chin. Her eyes went liquid black. When she spoke her voice was burnt sugar: “Looking out on the morning rain . . .”

Pebbles squeezed my fingers.

“ . . . I used to feel so uninspired,” said Mirella.

And then she proceeded to sing the rest of “You Make Me Feel (Like A Natural Woman)” a capella. So terrible, but so amazing. I held my breath. I wept. It was the most powerful religious experience of my life.