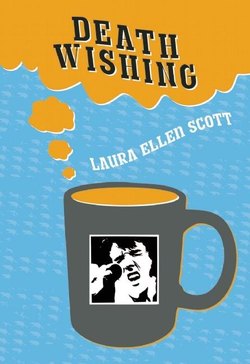

Читать книгу Death Wishing - Laura Ellen Scott - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2.

The cat-less night gave way to a still cat-less dawn, and I woke up a little cobwebbed from my indulgences. I stumbled into the kitchen and found Miss Pebbles seated at our sturdy old table, pulling the stone from a peach and flicking it into the trash while browsing through Andrew’s Hygienic Undergarments, a men’s corset catalog designed to mimic a pamphlet from the 1800s. Corset catalogs are abysmal, with spotty, all too realistic models photographed under high glare. Those thick ankles, raw skin, and howdy-howdy smiles are at odds with the dream.

A corset is a mechanical item of clothing that forces one to choose sides, if only because the sheer variety of corset styles and purposes makes one think about the dreaming wearer with tart empathy. Shall I assist young girls in their antebellum fantasies? Shall I enable tight-lacing fetishists? Shall I immobilize a damaged spine? Perhaps because of my own body image issues, I discovered that I felt something special for those men who sought to look more like women. I had no desire to look like or live as a woman, but I was aware that my attention to physical things (bodies, creation, barriers) squished its way through at least one feminine filter before it organized and labeled the world’s objects.

But to be more direct about it, I was a man reshaping himself, trying to lose weight in a city where the streets run with clarified butter, red spices, and sweet, sweet oysters. I wanted to use my crafter’s skills to assist other men as they reshaped themselves. To that end I had learned new things about old needs and desires.

A hand made garment can be the most perfect thing, as one thoughtful stitch follows another, accumulating into an aria. And opera is an apt metaphor here because that’s how it felt as I ascended into grace, pulling hand dyed thread through layers of brocade coutil. So similar to yet more lovely than writing fucking code all day. But that was my old life, dead and buried. Back in Northern Virginia I was the info tech director for a major defense contractor, now defunct and disgraced. These days, I lived with and worked for my son. Not that I minded, but it was strange being the grown-up and not having that matter one tiny bit.

I did like seeing Pebbles in our kitchen, even as I fought off the implications. She looked very fresh in a lemon yellow tank top and plaid men’s Bermuda shorts, leaning into our chrome and red Formica dining table that looked more like a 1950s Buick than a piece of kitchen furniture. Our kitchen was large with uneven floors, bright and sticky in the heart of our shabby Creole town home in the Marigny. We could never get that burnt grease and syrup smell to go away. Very different from the pretentious country kitchen of our old home in the suburbs.

I too was wearing shorts—sleeping shorts, and I looked a wreck. I yanked down my giant gray T-shirt and checked my fly. Nothing flopping, good. “Morning,” I announced with confidence.

“Mmm, hey,” she said brightly. I tried not to notice the glimmer of fruit pulp on her lower lip. The air was fragrant with chicory coffee, fresh brewed. A full pot, what a treat. One of the infrequent benefits of Val’s Romeo lifestyle was that some of the ladies he brought home were ambitious. They made coffee, sometimes breakfast. One child was caught organizing our silverware drawer; we never saw her again.

But making coffee was perfectly acceptable. “Val not up yet?” I asked. I poured a cup and slid into the seat across from her. She flipped through the catalog, her modest pink nails making a mockery of every image she encountered.

“You think we slept together,” she said. “We didn’t.”

“It’s none of my business.”

“He let me sleep on the couch last night. I was all weepy.” She looked up at me. Eyes bright and blue. No carnal residue. I took her at her word.

“The coffee is excellent.” I slurped to prove it.

She seemed to think this was an odd remark. “Can I come on your walk with you?”

“No.” My morning constitutionals were sacred. Then I thought about it. Boom, boom, boom. “Yes,” I said.

It was a romantic stroll in a very nineteenth century sense except that instead of picnicking amongst the tomb stones of poets (always an option around these parts) we took a tour of where certain cats once lived and prowled—the orange tom, the tuxedo twins, the half-pint-ever-pregnant tortie—and at one point the girl placed her hand atop my forearm.

It was sad and exciting at the same time. So terribly gothic. The gates surrounding St. Louis Cathedral were locked, protecting perfectly trimmed grass and red stone paths that wound around wild islands of flowers and trees. Normally the gardens would be crawling with cats. And later in the day after the gates were opened, this would be a place where people lay down for a bit of peace and shade—bums, tourists, students, artists, and cats, all shagged out like happy drunks. The sad tremor in Pebbles eyes suggested that she had read some part of my thoughts.

We wandered over to Woldenberg Park, half beckoned by the moan of a Russian barge and the morning-sweet scent of the river. Do other cities have so many oases? Each marvelous sculpture presided over its own wide territory so your heart could rest up before you happened upon the next. Robert Schoen’s “Old Man River” being the most arresting of these—seventeen tons of Carrara marble shaped into an eighteen foot male nude rising up out of the shrubs somewhat unexpectedly. The figure is soulful and stylized, not realistic, but the rough square representing his genitalia produces a sense of virility unmatched by known anatomy. This morning his bits were covered though. An enormous drape of white fabric was hitched around the statue’s waist, hanging down to where the figure’s massive thighs disappeared into its marble pedestal. A middle aged woman in walking shorts, sun visor, and New Balance sneakers stood at the statue’s base, tugging at the edge of the cloth, a bit shy about it, clearly wary that the authorities might swoop down at any moment. The drape slid down some, settling on the hips of the statue, making “Old Man River” look rather rakish and randy, as if he’d just popped out of the shower.

“Should we help her?” Pebbles asked.

“Whatever for?”

“Well she’s obviously striking a blow against censorship.”

“Do you really think so? My impression was that she was trying to sneak a peek.”

“There’s not that big a difference,” said Pebbles.

I smiled inside. Her careless banter would be fighting words out of a less pretty mouth. “You know what I thought?” I said. “I thought the Old Man was done up as a waiter to promote a food festival or something.”

Pebbles laughed. “So that’s where your head is at. You need some breakfast.”

We made our way to the Café Du Monde where Pebbles ordered hot, greasy beignets and a pint of whole milk. I ordered more coffee. The powdered sugar fell down her chin and onto her bosom, as is customary, and my heart started to click-click-click; lust and hunger are dangerous companions. Pigeons strutted everywhere, apocalyptic in number. One walked right over my shoe top, a thing that had never happened before. “Away, little bugger,” and I sort of soft-booted him into clumsy flight. Pebbles thought that was cute of me. I began to feel unreasonably handsome.

“So,” said Pebbles, tugging about fifty little napkins out of the dispenser on our table, “Corsets, huh?” She began scrubbing her fingers free of all traces of sugar. She was done eating, but there was one beignet untouched on her plate. Unbelievable.

I braced for an emasculating interrogation.

She sucked her teeth. “Isn’t that really complicated? I mean compared to making capes?”

“And what would be the transitional garment, in your view?”

She shrugged. Cream colored shoulders with freckles. Strawberries and cream. Damn. “Dunno. Belts? Hats? Oh wait—hoods,” she said, convinced.

It was early for it, but a “character” waded through a sea of pigeons clogging passage from the Café patio to the steps that lead up to the Moon Walk. Moon Walk was what they called the boardwalk along the river, named for good old Moon Landrieu, the politician credited with revitalizing the city in the seventies. This morning, one of the beneficiaries of that revitalization was already inebriated, all bright and pink in a bass (the fish) covered shirt and wearing an odd round straw hat with a shallow crown. Someone must have told him before he came down south, get yourself a wide brimmed hat, and stopping short of buying a sombrero that’s just what this fellow did. As I said, he waded through pigeons, making a general nuisance of himself. He shouted to no one in particular, “Satan hates Faggots!”

The disembodied reply was, of course, “So he must hate you!” Not clever, but there you have it.

“Fuck you wearing?” some other voice inquired.

The man insisted, “God loves me!”

“He must!” And this drew some chuckles.

I murmured to Pebbles, “The gentleman’s attitude is unexpected.”

She agreed. “From a distance, he looks more like the flexible type.”

We would normally ignore the behavior of impaired louts, but that round hat distracted me. I could barely keep from staring. And then Pebbles put her finger right on it. “You get those at the craft store,” she said. “You know, for centerpieces, dried flowers, that sort of thing? You hang ‘em on your door.You’re not supposed to wear the damn things.”

“Yes, of course, of course. My lord, how does he keep it affixed?”

“Suction of ignorance is my guess.”

We were having such a good time. A heavy Vietnamese woman in a smeared white apron and paper hat arrived table-side to collect our payment, and she too had an opinion on our early morning entertainment. “Mmmm-mm,” she blew, as we watched that blessed fellow teeter off towards Jackson Square. “I ain’ ready for that. Too early inna day.” Her accent came straight out of Plaquemines Parish.

Food is too cheap at the Café Du Monde, and leaving a properly calculated tip is embarrassing. I urged Pebbles to leave with me before our server returned with my change. We should have gone back to Esplanade then, but as with all experiences pleasant and complete, it is human nature to extend the moment into something weird and iffy and potentially ruinous. We drifted towards the Cabildo, and as the sun rose to burn off any cool remnant of dawn, the number of joggers, breakfast seekers, and first-minute shoppers increased, all of them plowing their way through pigeons now congregated big time in front of St. Louis Cathedral as if the archbishop himself was fixing to toss out some communion wafers or holy popcorn or whatever.

During our stroll I learned a few things about my lady Pebbles. It seemed she haled from a dry county in Arkansas, a refugee from a two year Christian college through which she visited New Orleans as part of a program to help folks rebuild their homes. It was supposed to be a six week mission, but by the program’s conclusion Pebbles hadn’t done much of the Lord’s work; instead she secured employment and a tiny walk-up on Esplanade. She was currently employed as a barista in an un-famous internet café, and it was her best job so far—she’d tried a little stripping, a little bartending, a little house cleaning, all the conventional service gigs, but pulling coffee meant she worked in a reliably air conditioned environment, and her nights were mostly free. Free for what? Free to sing the blues, of course. While she was waiting for divine inspiration to tell her what she was going to do with the rest of her life (and she did not want to return to college, thank you), she liked to sing at open mic nights. Checkpoint Charlie’s mainly.

That settled it. I had to get out more. I told her I’d like to hear her sing some time.

“You sure about that? Because I’m damned awful. I just get up, wiggle around and yell a couple tunes for the folks who are too drunk to go home yet. They’re real appreciative, but the musicians pretty much think I suck.”

“And you love the blues that much?”

“Not really. But that’s what people want to hear from white girls around here. I prefer honky-tonk, like Loretta Lynn when she was doing those ‘Fist City’ type songs. Those I can sing, but players around here don’t like to rock so much.”

Normally, if the day is fine, you’ll come across a little pick up band installed on the benches in Jackson Square, maybe sharing the territory with a palm reader or a juggler or homeless druggie Bobby Rebar, dancing his fool head off. But we were too early for that, encountering instead a lone tuba player seated on an overturned white plastic bucket. He was an elderly Creole, somewhere between sixty and two hundred years old, and his instrument looked like it had gotten caught in the undercarriage of a runaway bus. He wasn’t playing, not just yet, but his lips were poised over the mouthpiece as he eyed passersby, silently and unsuccessfully willing them to gather. You gotta give the people what they want though, so he commenced an unenthusiastic rendition of “When The Saints Go Marching In,” one of the few options for solo tuba. Some folks slowed down to listen, but I had the sense he wasn’t playing for them so much as he was calling to his tardy brother musicians: Hey, help me out here!

Unfortunately, he managed to attract our mad hatter, who sort of planted himself ten yards away, eyes ablaze as if receiving signals that no one else understood. He’d scored himself a refreshment, a large white go-cup full of pink frost, and he sucked on the straw like he needed a brain freeze to shut out the nagging voice of God. I began to worry for the pigeons at his feet.

There was tension between these men. Predator and prey. A bit of nervous fear in the tuba player’s eyes.

The hat man sucked hard, as if that plastic straw was his portal to glory, and his face changed colors. He finally let go and gasped a squealing breath, the quality of which captured my attention and that of many others in the square.

Then he was down. I heard a flesh muted crack. An explosion of pigeons opted not to catch his fall in favor of forming an avian cloud to hide the shame of his collapse. But pigeons know how to rid themselves of strong emotion, and in a split second they dispersed, settling just a short hop away from the man’s still form. He was face down. At first it appeared as if he were horribly, impossibly injured, but that was because he’d landed on top of his hurricane. The pink, icy ooze squirted an unfortunate trajectory across the bricks from about where his heart was located. It was not gore, obviously, but suggestion can be a powerful thing. Some good soul screamed for our prone lunatic whose head was now entirely obscured by his ludicrous craft store hat.

He moved his arms. Hands tentative as they sought the push up position, and that small sign of life sent a wave of relief among those who had paused to watch. There were six or eight of us, enough for a small concert. No doubt the tuba man was pissed.

When Pebbles touched my arm, I felt emboldened. “Sir,” I said firmly.

Two palms to the ground, testing his weight. He groaned.

“Sir, do you need assistance? Should I call for help?”

“Let him sleep it off,” someone suggested, and there was agreement from others. Hat Man had made himself popular, all right. I could only imagine that he’d made a full morning out of expressing his charming opinions.

He groaned again, made another move to raise himself. I did not want to touch him. I sort of leaned over, but away so he couldn’t catch me with some drunken, round house move. A mule and carriage clopped onto the scene, and the driver paused to scare up custom. “Any y’all want to ride?” He seemed unimpressed by our unwell friend.

The hatter made a forceful move and heaved himself over onto his back.

“Shit,” said about four people at once. His nose was smashed, and blood painted a thick, filthy stripe out over his mouth and down his chin and neck, pooling on his shirtfront where the bass no longer appeared indifferent to their situation. The pink libation clashed with the red blood, and it looked as if his torso had been used as a fish cleaning station.

I’m not trained in these matters, but I crouched next to him, and another man joined me. Several onlookers used their cell phones to dial 911, and all I could think was that there didn’t seem to be a way to stop the bleeding without pushing stuff into his head.

Pebbles dropped some of her unused napkins from the Café down to us—I don’t know why she kept them—and the man who knelt with me accepted them gratefully, but then he too became indecisive. He held the tissues in his hand and hovered over the wound, unsure of where he could do any good. Our man’s nose was absolutely obliterated; it looked like he’d been shot in the face.

His eyes were open, zig zagging like an animal. Then they closed. “I think you need to stay awake,” I said. A siren burst, not too far away. “Someone’s coming sir. It won’t be long.”

Then the man honked like a goose, and flecks of blood and other particles sprayed upward. I caught most of the gory sneeze, and my helpful friend caught a bit as well.

“Oh my God, Victor!”

I clamped my lips and eyes shut, but it was too late. I could taste copper, could feel hot specks on my skin. I lurched back. The crowd gasped. We all shared the same horrible, unchristian thought, underscored by what the mad hatter managed to declare next, his voice a thick, nauseating thing:

“I’m dying. I know it.”

I kept my mouth and eyes sealed. I didn’t even want to God-damned breathe.

“Gimme your water!” Pebbles’ voice sounded like a crow. Subsequently I detected a scuffle, which was probably her wrestling a plastic bottle out of some tourist’s fanny belt. She was by me then, trickling water on my cheek. “Hold still,” she said, her instruction hardly necessary. She daubed at my face with a wet napkin. I stayed still and tight. I had to trust that she could do this right.

“I die,” croaked the man I’d felt compelled to assist. “And I wish, I wish . . .”

Pebbles tells me I was forgotten then. That the possibility of my infection from the bloody sputum of a homophobic raving drunk was released like a vapor and replaced with an entirely refocused sense of horror. I remember someone pushing me back, but still I refused to open my eyes. The uneven pavement below me was cool, but the sun targeted my clenched face and I saw red, literally. Like it was some kind of sick joke.

The small crowd descended upon the man who seemed prepared to utter his last words. Pebbles’ napkins were put to immediate use, and there was no more uncertainty. The group wordlessly colluded on a divers hands approach to curtailing his freedom of speech by committing an act of involuntary manslaughter. Paper napkins covered and filled all the holes in the poor man’s face. He was unable to complete his wish, all right. He was also unable to breathe, right up until the paramedics came marching in.

And he was a drunken liar. Gerald Pollin was not dying, he wasn’t even close to dying. And he carried no communicable diseases, though not for lack of trying. Apparently he’d come to New Orleans intent on becoming someone new via sexual experiment, but so far no one was willing to lend a hand unless Gerald was willing to fill it with money first. And more than horny, Gerald was cheap. More than cheap, he was a drunkard. Two days into his adventure all the rejections he managed to collect took the spirit form of the ignorant woman who raised him, and he found himself raving in her voice. What a meager inheritance.

And what he gave to me was paranoia. For the first time since I moved down south, I felt real fear. I sat in an examining room with Pebbles who bided her time perusing a colorful pamphlet about stroke symptoms. She’d insisted on coming with me to the emergency room, but before that she’d tried to convince the paramedics to take me before poor Gerald. It didn’t work, and her attitude was not very attractive, but there are rare moments when a screeching, shrill woman is the only person on your side, and you couldn’t be prouder of the spectacle she was willing to make of herself.

There was nothing wrong with me, but we were waiting for the Alprazolam to take effect, and the doctor thought we’d be better off cooling our heels in private. Since Katrina it’s a whole lot easier to get anti anxiety meds through legitimate channels, which is not to say I didn’t fully deserve a little chemical help at the moment. And since cancer had been wished away, medical centers no longer processed patients like cans in a factory.

The edge fuzzed for me eventually, and the bitterness in my throat became stale. Somewhere else in this cigarette stain colored hospital Gerald Pollin was having his face restored as if it were the infrastructure of an ancient city, with pipes being laid and walls being reinforced. He, and the rest of us, would be better off with the Las Vegas approach: implode the fucker and start from scratch. I wondered if he’d had this sort of thing done before, and if the reason his nose seemed to shatter like marzipan wasn’t due to a previous reconstruction. Whatever. He was in pain. If not now, then soon.

Gerald Pollin was an asshole, but he wasn’t meaningful enough to make me feel this defeated. He was an accident. He was banal. He simply didn’t possess the power to trouble me so deeply. And to be honest, I had a hard time fixating on him, especially after I sussed out his inborn limitations. There was no Demon Gerald, so what had me so rattled?

Pebbles recognized that I was ready to move. She asked, “We gonna call Val yet?”

“Uhm. What’s today?

“Friday.”

Good then. I hadn’t missed Sunday. In a tourist driven economy you can lose track of days, because every day is an occasion for parties, both heartfelt and hollow. “Death Wishing,” I said out loud.

Pebbles waited. She’d seen trauma before, apparently.

I told her, “A friend of mine is giving a speech Sunday. One of the Wish Local events. Would you care to accompany me?”

Pebbles settled in her bones, becoming all women at once, and what came out was very measured, closed off: “Will it cost anything?”

“No.”

“Val coming?”

“He might just.”

“Okay.”

“What happened today—” I wanted to say something that would isolate the experience and rationalize the behavior of all involved. We weren’t going to be questioned by any authorities, especially if we all remained silent, and even if Gerald retained memories of the trauma he was entirely unreliable. That left us with our own internal judges to appease. For the first time I was grateful for having been incapacitated by hysteria; I don’t know how I would have behaved otherwise. All I know is that up until today I had been living a parallel world where Death Wishing was no more real to me than the latest scandalized celebrity. It was an earthquake, but in another country that only existed on the nightly news.

I wanted to say something about it all. But Pebbles was staring me down something fierce, and all of a sudden I felt as if I had no right to say anything at all.

I was nothing, right? Just a moony old man to her. She took my hand, and I hopped down from the exam table. She was going to lead me down the hall. She was going to guide this shuffling fool out the door.

I bit down: and what did you do my lovely girl? What side did you take when Hat Man Gerald opened his poisoned mouth? Oh yes indeed, paranoia had me now. Answers are never as important as questions.

Pebbles made a move to replace the stroke pamphlet in its holder (a minor relief that she didn’t think we’d need to take it with us), but she ended up knocking the entire batch to the floor. She squatted to retrieve them and the whale tail of her thong breached from the waistband of her shorts. The Alprazolam granted me permission to stare at her backside, and I found myself reading a line of red words printed on the pink elastic waistband:—llo Kitty Hello Kitty Hello Kitty Hello Kitty Hello Kitty Hello Kitty Hello Ki—

I held my breath and made a wish. Girl was gonna kill me for sure. And Death Wishing? That mysterious bitch. I honestly thought she would pass me by.