Читать книгу Jesus the Teacher Within - Laurence Freeman - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

The Key Question

The Lost Continent of Atlantis or Shangri-La, Treasure Island or the world of Sherlock Holmes, were not more magical to my childhood than Bere Island in Bantry Bay in the County of Cork. I had not much sense of its geography or of the life really lived there but it burned as one of the most luminous centres of my imagination.

My mother was born on the West End of Bere Island in 1916. She left for England at the age of eighteen, married an Englishman and did not return to her place of birth for half a century when I took her back shortly before her death. Yet the relatively small proportion of her life that she and her ten brothers and sisters lived on Bere Island had an enormous and enduring influence. It coloured their imaginations and shaped their characters. It was the womb, or cauldron, of the myths, legends, histories and symbols which helped them, and later their children, articulate the meaning of their lives. I was proud to learn I was related to the kings of Ireland until I later discovered how many kings there were. The stories and legends of the island, of Irish history and particularly of the O’Sullivan Bere clan enlivened our family gatherings on five continents.

Personally, I constructed a wonderful fantasy about Bere Island and about Ireland in general as I grew up in London. It became a personal myth that did not need facts or even much sense of history. I longed to go there and at the age of eleven made a disastrous visit. My first disillusionment was to see electric light on the streets of Dublin as the plane landed. I had expected gaslight and horse-drawn carriages. The problem with Bere Island, when I got there a few days later, was different. It was too primitive and I felt a very self-conscious and adolescent Englishman.

Years later, in my thirties and as a monk, I was drawn back there again for periods of prayer and solitude. Its meaning had changed for me. Seeing Bere Island more clearly was not easy with so many layers of cultural myth and personal fantasy to clear away. But asking what Bere Island was for me helped me in the long hard work of self-knowledge. Valuing the power of my roots there, but learning to grow up in my relation to it and to shed my fantasies and false expectations changed me too.

‘And you, who do you say I am?’1

Who is he? This simple, timeless question rolls down the centuries. The answer is simple, too, but not easy. If we choose to listen and to respond to this question of Jesus, the way we live, think and feel is transformed. The transformation happens because the question brings us to self-knowledge and self-knowledge changes us. We can answer such a question only when we have been simplified by long and deep listening.

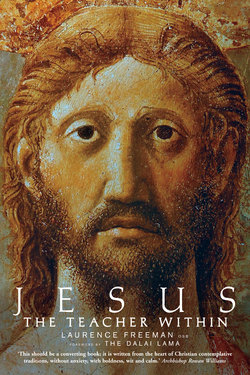

Every culture has its own images of Jesus and so no response can ever be the final answer. In a fourth-century Roman villa in Dorset there is a beautiful mosaic showing what seems at first glance to be a typical portrait of the young god Apollo. When you look closer you notice the chi-ro Christian symbol2 which identifies it as one of the earliest pictures of Jesus. For many British empire-builders of the nineteenth-century God, and therefore His Son, were quintessentially British. Baptism and British citizenship were closely related. In 1988 the American Senate was debating a proposal to spend more money on teaching foreign languages in state schools. A senator opposed it. The whole world was learning English now, he said, so why should Americans waste time learning other languages? To clinch his case he concluded, ‘If English was good enough for Jesus Christ, he said, it’s good enough for me.’3 Our thinking about Jesus, the way we respond to his question, is culturally conditioned.

We can only imagine Jesus with the means provided by our cultural and personal imagination. Most of us are not scholars with in depth knowledge of the cultural norms of the ancient Middle East two millennia ago. And even if we were, we would still be constricted by our personal and cultural point of view. Once we have pictured Jesus in our imagination, it is tempting to enrol him in support of our opinions and prejudices. The Jesus Christ we call to life in our imagination today, in our post-Christian and post-modern world, is a very different reality from the Galilean Jew of humble origins who was born when the emperor Augustus ruled in Rome and who was crucified by order of Pontius Pilate on a small hill near an abandoned quarry outside the walls of Jerusalem. Innumerable images through the history of Christianity, the world’s largest and materially most successful religion, have been developed to describe who Jesus is and what he means.4 Because of the distance between the historical and the imagined Jesus, Christians often seem more concerned about promoting their Jesus in support of their moral or social opinions than in discovering who he really is.

Who he really is is far more than who he historically was.

According to the author of the Letter to the Hebrews, Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today and tomorrow.5

How can this timeless identity be described? From the gospels it is clear that Jesus avoided titles that defined himself too narrowly. When he called himself Son of Man he was sometimes saying only ‘I, a man’ as when he remarked that the ‘Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head.’6 But even this single title has a wide range of meanings: from a circumlocution for the first person pronoun to the One who will come in glory to judge all people. On other occasions, the ‘Son of Man’ is associated with the authority that bestows forgiveness of sin and power over the sabbat7 This simple title sounds many chords. It evokes the figure of the prophet of Ezechiel, the fragile humanity of all the prophets and the vision of Daniel where one like a (or the) Son of Man appeared as a figure in celestial glory. In the passion and resurrection predictions in Mark’s gospel (Chapters eight-ten) this ancient title is used to show just how directly and compassionately Jesus relates to his fellow human beings. It also explains why he suffered the prophet’s fate. But neither ‘Son of Man’ nor the many other titles by which Jesus has been known can adequately express the response that his simple question invites.

Jesus clearly seems to have wanted people to think about who he was: not merely in received biblical or theological terms but in terms of their personal relationship to him. To ask who Jesus is implies who is he for me, to me, in relation to me? This is true, of course, of all human relationships. How else can I say who you are except in relation to me? Who am I in your eyes except in relation to you and who you see yourself to be?

When Jesus says he is the Son of Man he is stressing the simply but profoundly human way that he relates to us and we to him. This one expression, drawn from the idiom of his time and region, also shows how anyone listening to his question must first see him in his cultural context if we are to read the gospels intelligently. Christians, too, need this informed intelligence for their faith to grow. Their understanding of Jesus leads them to a deeper understanding of God precisely because their relationship to Jesus is grounded in his humanness. To emphasise the human nature of this relationship is not to say it is mundane or superficial. It leads to an extraordinary discovery of the full meaning of humanness. One consequence of this is that when we ask who he is we will always be led to ask who we are as well. It is always a specific person who knows Jesus. He can no more be reduced to an abstract definition than any human being. It is primarily as a human being that Jesus wants to be known by other human beings.

This is how Jesus puts the question in the gospel of Luke:

One day when he was praying alone in the presence of his disciples, he asked them, ‘Who do the people say I am?’ They answered, ‘Some say John the Baptist, others Elijah, others that one of the prophets has come back to life. And you, he said, ‘who do you say I am?’ Peter answered, ‘God’s Messiah’.8

Before leaping in with an answer, as Peter did, using a term charged with meaning for him, we might wish to stay silent a moment. In that silence we could reflect on the nature–and the power–of the question Jesus poses, just as a question. We should make sure we have truly heard the question before trying to get the answer right.

Important questions create silence.

Early in his first book on meditation, Word into Silence, John Main9 stresses the importance of the right question rather than the right answer. Get the question right before getting confused or intoxicated by the variety of answers. First of all, to hear the question demands that we pause, pay attention and repeat the question. John Main uses the myth of the Fisher King in the Arthurian cycle of stories to describe the power of a question to transform the world.10

Parsifal, a knight of the Round Table, meets Anfortas, the Fisher King, who has been wounded by a lance through both thighs. The king is restricted to lying down and fishing from the bank of a river. Around him his kingdom languishes, a wasteland of freezing mists. On his first meeting with the Fisher King, during which he actually sees the Holy Grail, Parsifal does not ask any question of the king. This is a mistake whose impact he soon experiences. His failure to ask a question threatens the very existence of the Round Table, the symbol of global order. Realizing his sin of omission, Parsifal swears never to spend more than two nights in the same place until he has found his way back to the King and discovered the meaning of the Grail.

After five gruelling years he finds Anfortas’s castle again. Going straight up to the king, who is still lying prone with pain, Parsifal poses his question: ‘Who serves the Grail?’ Immediately the Grail appears before them. Parsifal falls to his knees and prays that the king’s suffering may be ended. Then he turns again to Anfortas and puts his second question, ‘What ails you?’ Instantly Anfortas rises healed. With the king’s newfound wholeness, the whole land is restored to life and fertility. Trees flower; streams flow; animals breed. Parsifal had simply asked his questions: one about the meaning of life, the other conveying compassion. The story is not preoccupied with the right answers to these questions but simply the caring, mindful way in which they are asked. Questions that can work such wonders just by being sincerely asked are redemptive questions. They must be heard and attended to. Then they change and renew the world.

By retelling this myth John Main addresses the dilemma of a Western culture which has for so many people today become a disabling and barren wasteland: a polluted environment and increasingly unstable ecological system, a sense of psychological isolation and social alienation in urban life, chronic levels of anxiety and increasingly dysfunctional families, shamefully widening gaps between rich and poor, addictive lifestyles and demeaning entertainment, unsupported institutions of democracy and manipulative media, a sense of powerlessness and abandonment among the young, confusion between personal and social morality, the loss of religious authority and the dangers of shallow syncretism. The malaise of the modern soul can be redemptively touched by those timeless myths that remind us of the eternal questions. These are the questions we must return to, not with easy answers but with new reverence. We have reached the point, John Main believes, where we do not need more answers, instant diagnoses and solutions. We need to relearn how to listen, humbly and profoundly, to the redemptive questions.

This does not imply that redemptive questions are in themselves magic solutions. They initiate a process of redemption. This means a conscious process of healing and of liberation from all that blocks joy, compassion and creativity. They liberate us, for example, from the grip of illusion and prejudice, from obsessiveness and fanaticism, from the fear of strangers and the prison of hatred. A redemptive question is not like other mundane questions. It does not expect an ordinary, rational, correct answer. Instead, it opens up a deeper level for experiencing the truth. The well-timed question in psychotherapy can cut the psychological chains of many years–and why do you think you said that? Or simply, what does that mean to you? Such open questions also operate at the root of the spiritual quest and trigger definitive awakenings.

Unlike answers, questions attract and hold our attention. They are irresistible, like a half-open door. Answers, especially wrapped in dogmatic certainty or claiming to be right in this form for all time, soon come either to bore or oppress us. Even the best answers can be as unwelcoming as a door banged in our face when they exclude alternative responses. Rather than giving answers and making rules Jesus called people to experiential knowledge. By asking questions or telling stories he invited his hearers to a personal discovery of truth, a redemptive recognition of reality. Throughout the gospels it is his questions which magnetize and capture our attention. Often they also deftly turn the attacks of his hostile critics back on themselves.11 It is by questions that he leads his disciples into a deeper understanding of who we are and who he is. These are the inseparable twin insights of his gift to humanity.12

Often, however, answers can be fatally attractive. They make us feel we can bottle the truth in a slogan, a dogmatic definition or scientific formula. ‘How many floors does the Empire State Building have?’ has an, easy, once-for-all answer. To deeper questions than this our responses require continuous and deep listening. Philosophy makes no progress but keeps returning to the basic questions asked by the first thinkers. This does not mean that truth is merely a subjective judgement or that there are no simple truths about right and wrong (do not kill, do not tell lies, help the poor). It means that the ways we formulate responses to these questions are constantly changing. Cardinal Newman (1801-90), one of the greatest of Christian theologians, wrote The Development of Christian Doctrine to show that one of the tests of a true answer is precisely that its way of expression evolves over time.

When we stop questioning we die. We only stop asking questions when we have despaired of life or when delusion or pride have mastered us. All the same, we hardly ever give up dreaming that a single definitive formula could solve all life’s problems. The temptation is very strong to cheat on the challenge of the mystery of life by reducing it to the status of a problem. So, people go on demanding absolute answers even to the redemptive questions. It is precisely these kinds of questions, though, that frustrate the ego’s attempt to control the mystery. The right questions constantly refresh our awareness that life is not fundamentally a secular problem but a sacred mystery. Mysteries are not solved. They are entered upon and they embrace us. Responding to Jesus’ question about himself and us involves not a discussion but a way of life. His disciples were first called ‘followers of the way’.

Every spiritual tradition treasures the power of the question. In Zen practice a koan is a question thrown to the rational mind which arrests the ego’s attempt to control reality. Like a key the koan opens consciousness beyond reason to truth as unfiltered experience, pure knowing. Receiving the koan from the teacher, the student’s rational mind may recoil in anger and frustration as it futilely tries one clever solution after another. And the ego’s need for control appears to be endless, even for some would-be Zen practitioners. In a bookshop I once saw a paperback enticingly called A Hundred Zen Koans–and their Answers!

Answers are most dangerous when we egotistically fight to defend them against a broader vision of the truth. Visiting Bere Island in my thirties made me rework some of the answers I had received as a child to questions about my family history. This involved me in both emotional and intellectual change. Ideologically or theologically we can also cling to familiar answers until they seem to be the only answers. Then they can be used to justify the condemnation and rejection of others. Even the most tolerant people cling tenaciously to their views. Listen in to any conversation and you see how quickly people defend their own answers by attacking others. Then, hopefully, we recognise how we are no different! Set answers breed conflict and prejudice. Wisdom and tolerance are found by listening to the important questions, keeping them open, pausing in silence to listen again and again.

Over the past two thousand years there has been no lack of answers to that searching question which Jesus put to his close disciples one day in the village of Bethsaida: ‘Who do you say I am?’ Peter, the impetuous leader of the disciples was characteristically quick to reply. It is the first recorded answer to a question around which two millennia of Christian life has formed. It was brief: ‘God’s Messiah’, he answered. Many church councils subsequently wrestled with the right way of expressing a longer response. In AD 381 the Nicene Creed, as expanded at the First Council of Constantinople, clarified the Christian perception of the divine identity of Jesus. This is the grounding insight of faith embedded in the Creed most universally recited by Sunday congregations around the world to this day. Bathed in biblical language the Nicene Creed can be used as a beautiful meditation on the mystery of who Jesus is in relation to biblical revelation:

We believe in one God, the Father, the Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all that is, seen and unseen. We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ, the only Son of God, eternal begotten of the Father, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten not made, of one being with the Father. Through him all things were made. For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven: by the power of the Holy Spirit he became incarnate from the Virgin Mary, and was made man. For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate; he suffered death and was buried. On the third day he rose again in accordance with the scriptures; he ascended into heaven and is seated at the right hand of the Father. He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead, and his Kingdom will have no end. We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the Giver of Life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son. With the Father and the Son he is worshipped and glorified. He has spoken through the prophets. We believe in one holy, catholic and apostolic church. We acknowledge one baptism for the forgiveness of sins. We look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come. Amen

What does this mean and how do we experience its meaning? It can be read and pondered sitting in a library but a quite new dimension of meaning is discovered when this creed is sung by a community of worshippers at the Eucharist. The power of its meaning is then understood to be more than cerebral. It is felt to be reaching deep into the intelligence of the heart.

There have been many other attempts to answer the question of Jesus. In AD 451 the Council of Chalcedon,13 in over three hundred carefully technical words, defined its answer through the dogma of the two natures in the one (divine) person of Jesus: two unseparated but not confused natures. The seminal Councils of Nicea and Chalcedon, and the subsequent centuries of Christological debate have reverently, and sometimes irreverently, attempted to settle the question of who we say Jesus is once and for all. Often in the heat of polemic the debaters have forgotten the essentially personal tone and the dimension of mutuality in the actual question Jesus asked. Not just ‘who am I?’ but ‘who do you say?’

In response to Peter’s answer Jesus ‘gave them strict orders not to tell this to anyone.’ He did not reject Peter’s confession of faith. His reason for strictly instructing them to keep silent becomes clear in what follows immediately in the next section of the gospel. Jesus links his question to the personal cost of discipleship. The cost is nothing less than everything: to leave self behind and to imitate the self-transcendence of his Cross and Resurrection. By binding his disciples to silence about the answer to his question he was doing what he did when he ordered them not to publicise his miracles. His messiah-ship, like his powers, could easily divert people from the real challenge he was presenting. Everything else was a side-show beside the central challenge of listening to his question with a depth of attention that would awaken self-knowledge. His question summons a response from a silent depth within the heart itself.

Silence harmonizes the many different answers that are possible and will test their authenticity. We can only validly say who he is when we know who we are. Silence is the source of both insight and tolerance. For example, in Matthew’s account of the scene Peter’s answer is more elaborate and is commended by Jesus. But the same injunction to silence follows:

Simon Peter answered: ‘You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God’ Then Jesus said: ‘Simon son of Jonah, you are favoured indeed! You did not learn that from mortal man; it was revealed to you by my heavenly Father. And I say this to you: You are Peter, the Rock; and on this rock I will build my church, and the powers of death shall never conquer it.’ He then gave his disciples strict orders not to tell anyone that he was the Messiah.14

Some scholars think that Jesus’ response to Peter’s answer suggests a later addition to an original text or story. For his readership Matthew wanted to emphasise Peter’s preeminence among the apostles. Luke’s version does not mean we should never give a thoughtfully worded answer to the question. Matthew’s account does not say there is only one possible formula. These differences between the two gospels illustrate how all the gospels must be read, not that they are contradicting each other. Matthew and Luke both show Jesus emphasising silence. He did not seem to believe that his mission would be helped by his being popularly acclaimed as the ‘messiah’. The same injunction to silence is found in the ‘secrecy motif’ of Mark’s gospel, the earliest of the four gospels, concerning miracles. Mark also reports Peter’s response but without Jesus’ comment.

The identity of Jesus can be validly expressed in diverse and even divergent ways. The most eloquent and universal expressions are at home in silence. The main purpose of this book is to stress the often neglected value of silence in responding to the question of Jesus that, more than any other question, defines our relationship to him. It is the indefinable silence at the heart of the mystery of Jesus which ultimately communicates his true identity to those who encounter it. And it is a universal identity. He belongs to the Jewish tradition messianically. But he has come to belong no less to the rest of humanity. Every religious tradition will employ its own terms to describe him. If there is a unity in all these responses it will not be linguistic or theological but a mystical unity beyond words, concepts and images. We know the highest truth by love not thought: the Christian mystical tradition, together with its sister traditions, is sure of this. The silence of love, not logic, is the sharing of one’s self-knowledge with another.

Jesus’ question welled up from the silence of his own self-knowledge. He posed it while he was ‘praying alone in the presence of his disciples’. This context of prayer is all-important for understanding his question. It is the context of discipleship and spiritual awakening: community, friendship and shared consciousness. Let us look at what this context of prayer, in which the defining question of Christian identity is first raised, means for us today. By understanding prayer we learn how to read the gospels, the essential texts of Christian faith. We also learn what discipleship means and how to see prayer as a journey of the soul into the boundlessness of God.

Who do you say I am? The answer is to listen.

Jesus is not there in history just to be looked at, examined, and judged. He is not here only to be observed, to be seen with the eyes of the body or the mind. He is to be known in relationship–known with the eye of the heart. When he is seen just as an object of scholarship or historical analysis, the perceptive faculty of faith is lost. Faith is the bonding-power of all relationships because it allows inter-subjective knowledge to develop. It disintegrates and degenerates into scepticism as soon as the person we relate to becomes an object. When we coldly objectify Jesus we miss our appointment with him. His power as spiritual teacher, liberator, healer and redeemer, the same today, yesterday and tomorrow, passes us by. He could work no miracles there because of their lack of faith.15

Of course, historical and critical faculties should be employed in reading the gospel and in investigating Jesus as a historical figure. To repress this kind of inquiry merely blocks the deeper understanding that resists rational analysis. We need to ask who the historical Jesus was and what he actually said. And what people said he was and what they say he said. But the ‘pursuit of the historical Jesus’ is the beginning not the end of the quest we embark on by listening to his question.

It all depends on how deeply we listen, how much time and attention we give to it. The quality of our attention enhances the way we ask all questions about him. It affects the way we encounter him as a personal reality because it moves the place of meeting from the mind to the heart. By heart I do not mean an emotional or physical centre. Heart is a universal term used by spiritual traditions to designate that centre of integrated consciousness where all ways of knowing are focussed. It is where sense becomes spiritual, where imagination may become insight. It is the centre and the wholeness of the human person. In the heart my self-knowledge and my knowledge of God are in harmony, the peace found beyond ego consciousness.

Discovering Jesus’ identity for us is not achieved through intellectual or historical enquiry. It happens in the process of opening to our intuitive depths, to deeper and more subtle ways of knowing and seeing than we are accustomed to. This is prayer and the experience quickly makes it clear that prayer is more than thought. It is an entry into an inner space of silence, where we are content to be without answers, judgements and images. Later in this book I will turn to meditation16 as a way, time-honoured and universal, of entering this inner space of the heart and developing the state of silence. For many, meditation, a way of faith-filled silence, has transformed religious belief, whether Christian or non-Christian from arid theory to vital personal experience. The silence of prayer that is deeper than thought and image enhances our knowledge of Jesus because it leads into the reality of pure presence. Our response to the redemptive question is not, however, a matter of either intellectual or spiritual techniques. Meditation is not a trick for answering the question of who Jesus is. It is, in my experience, a way of listening to the question more deeply and clearly.

The redemptive question requires selfless attention. To listen is to be truly ‘obedient’ as the Latin root (ob-audire, to listen) suggests. To grasp for an answer is symptomatic of distraction. The sign of scattered, superficial or intermittent attention during meditation, for example, reflects our repeated tendency to get lost in thought and fantasy. Similarly, a sign that we have stopped paying attention to his question or have filtered it through our own preconceptions is that we do not even answer the actual question he put. Overconfident answers usually address the question that no one has asked. Or they are the answers we were taught years before but which have remained untested in the light of experience. A further danger signal is when the redemptive question becomes boring. This is often the result of having lost respect for the religious authority associated with the question. The answer to this question is not a solution but an insight. Through the struggle of faith, and with the balm of grace, insight dawns. As science, art and religion can all testify, the actual source of insight remains forever mysterious.

Jesus asks Who do you say I am, not What am I or even Who do you think I say I am? It is an intimately personal question. If we do not feel its intimacy as disturbing–even intrusive–we have not listened to it. It is not twisting our arm however. Its authority is not violent but vulnerable, not forceful but humble. To ask a person who they really think you are is a declaration of love.

Redemptive questions illustrate what redemption means. This is important for all humanity, not just for Christians. If we can understand what Jesus, as one of humanity’s great teachers, is getting at in his question, we will see where he is trying to get us to. We will be the wiser for it. And wisdom is the principal value that human beings need to develop today. According to the Book of Wisdom, the ‘hope for the salvation of the world lies in the greatest number of wise people’.17

The meaning of any question depends on its context. ‘Are they off?’ means something different when you are at a racetrack, ordering in a fish and chip shop, or smelling a bag of old fruit.

Considering the context of Jesus’ question leads us to look at the gospels themselves and their tradition. We are alerted about how to read the gospels prayerfully. For the early Christians reading and interpreting the gospels was not an essentially academic and certainly not a journalistic undertaking. It was a means of entering contemplation and an integral element of salvation and enlightenment.18 It was both prayer and a preparation for deeper prayer.

As described in Luke’s gospel Jesus was ‘praying alone in the presence of his disciples’ when he put his disturbing question to them. The apparent contradiction is illuminating: how can one be alone and in the presence of others? We can be alone on a crowded subway train or at a party where everyone is a stranger. This is loneliness, knowing no one and feeling known by no one. But there is another kind of aloneness which is solitude. For example, when we meditate or engage in creative work we are solitary but not isolated. Alone, not lonely. All spiritual growth leads from loneliness into solitude. The recognition and acceptance of our eternal uniqueness is solitude. At first it can be more terrifying than loneliness because it dissolves the crowd around us and reveals instead the mutual presence of other solitudes, other unique persons. Solitude is the basis of all relationship. In solitude we run the supreme risk of paying attention to a reality other than our own. Whoever wants to find his life must lose it.

Jesus poses his most intimate question from his vast solitude. He turns to his disciples, his friends and companions, from the self-knowledge in which he has recognized and accepted himself in prayer. He is baptized in self-knowledge. He knows where he comes from and where he is going. The self-knowledge of Jesus, like all human self-appropriation, arises from the creativity of prayer. Prayer means growing in self-knowledge rather than merely performing or mouthing a set ritual. It is about paying attention rather than listing needs, making statements, articulating our intentions or even obsequiously saying please and thank you to God. Prayer underpins religion more essentially than religion legislates about prayer.

You are here to kneel

Where prayer has been valid.

And prayer is more

Than an order of words, the conscious occupation

Of the praying mind, or the sound of the voice praying. 19

Jesus’ piercing question highlights the intimacy which is discovered by sharing a spiritual path. This intimacy is the community of the True Self in which the many know they are one. Prayer is the expansion of consciousness within this communion of self-knowledge. It is light years beyond what our individual egos know about ourselves. When Jesus uses the first person pronoun (who I am) he claims the rare right to say I authentically. It is no longer the little me of the ego at which most of us are stuck.

All relationship is to some degree about sharing in self-knowledge. This does not mean merely what we know about ourselves and what can be verbalised or conceptualised. It is pure consciousness, simplified of self-reflection and free of anxiety. Childlikeness rather than philosophical cleverness comes closer to showing us what this means. ‘Unless you become like a little child . . . ,’ Jesus teaches. His question expresses his desire to share his self-knowledge. Behind this desire is divine ‘love–longing’–as the Upanishads call it.20 It is found deep in Jesus, in God and in the human being, and it unites God and humanity in their common thirst for each other. Behind the question of Jesus is the longing to be loved by those he loves. The selfless passion at work is the consuming longing to transmit the whole of one’s self to another. This is the ‘eros’ aspect of all love. But when this longing expands to embrace all others it has become ‘agape’. The meaning of the universal, selfless agape of the Trinity is that this passion for self-communication is at the very heart of reality. In the minutest atomic force, in the expansion of the universe and in every human relationship. Behind his question, therefore, is his personal insight into the nature of God as a communion of love.

The authority of Jesus, which his contemporaries felt both positively and negatively, flows from the well of his self-knowledge. He knows his life’s source and destination.21 Self-knowledge of this depth consists of more than information about ourselves. It is richer than the most perceptive psychological insight. To know who one is and where one has come from is a knowledge which can only be enjoyed in the ‘community of the True Self’, that is, in the knowledge of God which is love. It is known not by trying to possess it but by self-transcendence.

Self-knowledge is also humility. By putting his question in the way he does Jesus humbles himself and proves the authenticity of his authority. What authenticates it is partly the fact that it can be so easily misinterpreted. True humility is easily mistaken for pride. Some religious people are particularly skilled at masking pride as humility. When they encounter real humility they mistake it for an exceptionally good mask and enviously want to expose it. It is not so surprising that to many of his contemporaries Jesus appeared as a manifest egomaniac claiming, as they said, to be equal to God.

Perhaps this is why Jesus said the first will be last and the last first. His humility is the authority which turns the tables of the ego’s power.

It is never those hungering for power who recognise him. Humility of this intensity is revolutionary and dangerous. It upsets the balance of power constructed by egotism. The ego plays its power-game at every level: individual, relational, social and political. It must find the question of Jesus disconcerting because the question threatens to expose the ego’s need for total control. Jesus was playing with fire when he provoked the ego’s reaction to the true self. We can see it in ourselves daily. Hearing his question the ego rushes to dismiss both question and questioner. This simple question has all the revolutionary humility of a guru, a teacher, a rabbi and a prophet. Whoever truly knows himself can help others to know themselves simply by asking them who they think he is. There is no playacting in this. He communicates himself simply by being himself. Such humility allows the community of the true self to unfold towards us and to enfold us.

Redemption is knowing with our whole being who we are and where we have come from. It is the grace of the spiritual guide or guru to awaken this knowledge. By communicating himself through a gentle question Jesus invites our attention. This has the potential to become a relationship with him as our teacher.

The word guru is not a common term in Christian vocabulary. But that does not mean Christianity lacks a rich tradition of spiritual friendship and union with the guides we need for the inner journey–from the didaskaloi–, or teachers of the New Testament, to the monastic abbas and ammas of the Desert Tradition to the staretz of Eastern Christianity or the anamkara, the soul-friend of Celtic Christianity. The modern idea of a spiritual director can be a somewhat psychologised version of this ancient wisdom of spiritual friendship. In the gospels Jesus is called rabbi, or teacher, more often than by any other title. Yet it can seem strange to Christians to think of themselves as his students or disciples. This could only happen because they have been diverted by answers and stopped listening to the question–the skilled question by which any teacher awakens knowledge.

A Christian is essentially a disciple of Jesus. And he is their guru. Good disciples do not feel their guru is in competition with other gurus.

Tolerance, dialogue and collaboration are the challenges facing Christian disciples today. For the first time since the fourth century institutional Christianity is not bolstered up by a secular power that supports religious exclusivism. Christians are being invited to see themselves as disciples of Jesus in a new relationship to the disciples of masters in other traditions. Realising that Jesus is their personal guru is decisive for freeing Christians from engrained attitudes of imperialism and historical intolerance. They are then freed for dialogue and spiritual partnership with other faiths. The question by which Jesus relates to his disciples therefore also connects him to the spiritual search that is common to humanity.

Jesus is not seeking disciples to enhance his self-esteem. In fact the gospels tell how he let many opportunities for guru stardom pass him by.22 He saw many of his followers turn away from him because his teaching threatened them by its sheer personal authority. For this or other reasons it may not suit us to think of Jesus as our guru. We may not want a guru at all or we may feel called to another. Jesus does not condemn that decision. But even if this is how we feel about him we can still listen to the silence from which his question arises and touches everyone.

The word disciple derives from discere, to learn. A disciple is one who acknowledges that he has got something to learn and that his teacher, at least for the present, knows more. There is a paradox involved in acknowledging this. It implies a separation from the person in union with whom we are to learn how to transcend duality. Beyond duality lies the full participatory being of love. So in fact discipleship does transcend itself. The disciple goes beyond the teacher because the teacher goes beyond himself. This paradox–is the essence of the identity of Jesus. It is good for you, Jesus told his companions, that I am going away. Discipline is the way the disciple learns to enter this paradox–the discipline of listening, of silence, of reading with the heart, of meditating without desire.

When we are unaware of the stages by which relationship unfolds, we risk premature failure in every relationship we make. The first phase of romantic attachment seems like the end of everything. In learning to relate to Jesus, we begin by listening to his question, sitting at his feet. But as we hear his silence we find that we are inside his question, compassionately known by his self-knowledge. The mystical truth of the New Testament is that we are in a union with Jesus that takes us beyond every kind of ego-centred relationship with him. Christian fundamentalism, like all forms of fundamentalism, is arrested development–relationship that gets blocked at an early stage. In union with Jesus the disciple’s individuality, though not destroyed, is transformed. What else does love or death mean? As a second-century Christian writer put it:

For you in me and I in you, together we are one undivided person. 23

Deep prayer guides us beyond dualism into union, beyond ideas and images into reality. From the gospels it is clear that Jesus did not want hangers-on or devotees but full disciples or friends. Insight–into our being ‘in Christ’ and of his being ‘in us’, of our sharing the same God and Father with him24–dawns when egotism has given way to self-knowledge nurtured by the grace of relationship with him. We need duality in order to transcend duality. In other words we must work with the ego to transcend the ego. Similarly we need the historical Jesus to reach the Cosmic Christ. And yet we encounter the Jesus of ancient Palestine not as he was then but as he is now. Meeting him now we encounter everything he has ever been and all he will yet be.

In listening to the question which Jesus puts to humanity we are also hearing a call to self-discovery. Listening to him leads to listening with him to the mystery of existence at its source. This process is what makes the question and person of Jesus so relevant for the modern spiritual seeker. If we are to see Jesus as he is, and not just as our ego imagines him to be, we must learn to listen to his question in the very silence from which he asks it.