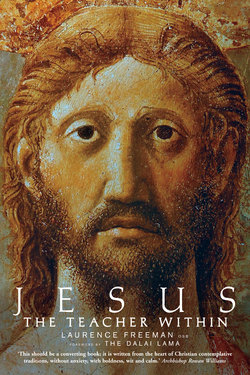

Читать книгу Jesus the Teacher Within - Laurence Freeman - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Faith and Experience. Faith or Experience? For many today the tension between the two has led to an unhappy polarisation of their spiritual journey. There is a great interest in spirituality but also great confusion about what it means. Polls show that increasingly we prefer to call ourselves spiritual rather than religious. Is this because spiritual means experience and religious means faith? And so we feel that as experience has the higher claim to be authentic, it is better to be spiritual than religious.

There is a lot to support this point of view. Firstly, the founders of the major religions do not seem to have thought of themselves as that, although they were all both deeply religious and spiritual. Secondly, religious leaders today, with some notable exceptions such as the Pope and the Dalai Lama, seem unable to inspire. And thirdly, the perennial tendency of organised religions to merge entirely with a culture and to fight with others is singularly unedifying in a world where globalisation and tolerance are valued so highly.

The problem is that faith and experience cannot be polarised so easily. Faith means more than belief, the dogma or tenets of religious systems. Experience means more than the good or bad vibes I get when I do this or that: it means the lifelong journey of becoming fully who we can be, who we really are. And religion is not so easily dispensed with either. We cannot be truly spiritual without encountering others on the same path and relating, with them, to those who went before us. Tradition is also a form both of faith and experience.

Jesus is an indispensable force in the achievement of any authentic spirituality. Even though most people have problems with the church–as do most church-goers themselves–the person of Jesus is one of the constant beacons guiding humanity beyond egotism and the violence of despair towards the higher goals it continuously sets for itself of kindness and serenity. As East and West meet and explore each other’s spiritual heritages in a friendship new to human culture, we are all encouraged to requestion the essential meaning, purpose and identity of our religious traditions. Perhaps this will help ease the conflict in people’s minds between faith and experience as we rediscover the essential unity and simplicity at the heart of our founders’ teachings.

For Christians the requestioning of their tradition has an obvious starting-point. It is the central question of the gospel around which the identity of a Christian disciple pivots: Jesus’ own question, ‘Who do you say I am?’ This book is really a play of variations on that theme. It is a lectio, a spiritual reading, of this question before some of the big issues of religious understanding: the historical reality of Jesus, the experiential and faith-meaning of reading the scriptures, personal conversion and naming one’s religious identity, the inner journey. And, running through it all, is the universal understanding that we cannot know anything, let alone God, without knowing ourselves.

This question I would suggest, is important not only for Christians. Those who follow another tradition but have their roots in Christianity can often carry negative baggage, misunderstanding and even guilt which this question can relieve them of. The response to Jesus’ question by a sincere practitioner of another religion, as the Dalai Lama’s response shows, can be highly illuminating for all, as well as helping to develop the dialogue that is so essential to the third millennium. For many Christians, too, this is a question they have never really listened to seriously or taken personally. Doing so will have a profound effect on their self-understanding as well as their sense of who he is. It awakens us to the need for silence and attention as the prerequisites for all listening. And it makes us appreciate better the noble attempts of the past–sometimes called orthodoxy–to respond to a question that can only be fully answered in a faith-filled experience of the Spirit.

However objective one tries to be about it, thinking of Jesus is inescapably personal. I should therefore, by way of example, express something of the personal experience of faith that has led to my writing this book. The first may seem more ‘experiential’, a one-off event; the other more of a process of faith, a long twisting journey. The point, it seems to me, is that they both express the same personal reality of unfathomed richness called Jesus.

Shortly after I became a monk, I was agonising over what I was doing with my life, who on earth or in heaven Jesus was or is, whether the church and all its baggage was only a massive collective self-deception, whether Christian faith gave sufficient backing to my odd and perplexing decision to be a monk. My questioning was not curious but desperate. I was not depressed but I was in great pain. Whether I was wasting or investing my life was what was at stake.

One evening as I was reading the gospel and had put the book down to think and pray I was suddenly filled with the only experience I could to that point really call praise. Suddenly and for no obvious reason I felt myself caught up in an orgy of praise and saw that it was both directed to but also through the person of Jesus. I knew that this was happening at the heart of the world–or at least of everything I was capable of understanding as the world. It was an ecstatic praise not a formal one, more like a rock concert than a church service. Yet its ecstasy was of the most deeply satisfying order and harmony imaginable. The words of the New Testament to him be all glory, honour and praise which had seemed exceedingly grey to me before now expressed a participation in the risen Christ ‘in glory’ in which every sentient being shares. Although for me Jesus was the hinge on which all this swung, the overwhelming conviction was that everyone and everything was involved. A great party is somewhere in full swing which no one is turned away from and where the fizz will never run out. Finding where this is happening and how to get there as soon as possible seems a good way of spending one’s life. This individual, to me ‘memorable’, experience has passed away in time. I don’t think of it much now. But I sense–maybe this is an aspect of faith–that what it exposed is always present, undiminished, and even always deepening.

A second, different kind of experience of Jesus came through a third person. My teacher John Main was a powerful personality. He never used his power to control others’ beliefs or behaviour. But to be near him was certainly to be influenced by what he believed and how he acted. When I first started to train with him my aim was not specifically to know better who Jesus was. That might have been a long-term goal but in the short term I had to begin to iron out my own problems and grow in self-knowledge. Gradually I came to see how deeply central Jesus was to John Main, not just as a religious symbol. I came to see how Jesus lived in John Main’s own person as a living presence, in a personal relationship that was hidden (mysterious) but not secretive. Perhaps this is why to hear John Main read and comment on the scriptures aloud so refined one’s faith. The words rang with the authority of his own experience. He was not always talking to or thinking about Jesus of course. For some religious people John Main was in fact a little too irreverent and worldly. But, from time to time, I would glimpse with awe the depth, intimacy and reality of his faith-filled experience. These insights accumulated and focussed my attention over these formative years. Perhaps this is essentially how all faith is transmitted. I did not at first know what to make of it. I did not seem to feel it experientially myself. But I was not sure. While I was wondering what to do I put the subject of how real Jesus is on hold.

John Main died at fifty-six. The future of his work of teaching Christian meditation, through the small community he had formed, seemed highly precarious. I was at a loss to know what to do except to continue meditating. I was prepared to see everything he had worked for collapse in ruins. What in fact happened reflected the Resurrection experience of the early Christians. The expansion of the meditation community over the following years seemed like a Pentecostal event, the burst of new life in the primitive church. It was often very turbulent too, but palpably a work beyond the power of the individuals concerned. This is not to say that the development of the meditation community was the creation of a new church. In fact the reverse was true. It was rather about the renewal of the existing church. I came to see that after every death there is resurrection. Within every resurrection there is something universal. Individual experience is part of a greater reality. So, the growth of a world-wide community of meditators became for me another seeing and feeling of the elusive but inescapable mystery of Jesus. It was not restricted to particular experiences but was more like the unfolding of a greater single experience. It was personal but in a sense that exposed the illusion of the individual as an isolated, autonomous existence. It grew partly from that relationship with Jesus that I had felt and in some way shared in with John Main.

Over the years the growth of the work he left behind has transformed my sense of the relationship between the living and the dead. For anyone interested in wondering who Jesus is, this question of our relationship with the dead is an important bridge to cross. The fledgeling Christian meditation community became a way to understand Jesus’ promise to his heartbroken disciples that his death did not mean he was abandoning them as they first felt. He would be ‘with them till the end of time’. I began also to understand that what enriches the heart of a person is not exclusive. It can and should be shared. Through others who shared their spiritual journey with me, including their questions, doubts, insights and fidelity, there came the incomparable gift of feeling the life of Jesus working in them, guiding and teaching them with compassionate personal precision. Usually it has been through the lives of others, rather than by focussing on my own experience, that I have seen the truth that he never leaves us.

Human beings will never cease telling stories. Our lives are understood when we narrate them. Similarly we first meet the question of Jesus through the stories we call the gospels. I am grateful for having grown up with them: the wonder of these stories is precisely that they speak to the child and the man. Coming to love them prevented the dogmatic approach to faith from becoming too dry. The Jesus in the stories always seemed more alive than the catechism. This book then is simply another way of telling an old story. It is one that belongs to humanity and so becomes fresher with every telling. The story’s effect on us, not an interpretation we are told to believe, constitutes its deepest meaning. But the story is now also embedded in a tradition of its own making.

In writing this book I found it helpful to refer to a small but highly charged element of my personal history: a small island in Bantry Bay, on the south-west coast of Ireland, where my foremothers came from. The relevance of this to my attempt to understand Jesus in the light of contemporary spirituality and its problem with faith and experience will, I hope, become clear. I hope it makes the book more readable. It should clarify the subtle relationship between imagination and reality, story and truth, past and present.

Mummy, what was Bere Island really like? My questions about it brought it alive and my mother and aunts (my uncles rarely got a word in) had plenty of answers. There were multiple answers to my question and they were nourished by memories kept alive by the art of retelling them. My questions about Jesus seldom met with the same depth and liveliness. It was not in catechisms but in people who seemed to me to genuinely know Jesus that I felt my questions about him could be answered. Gradually I learned to listen to his question for myself.

Reality, like the meaning of good stories, never stops expanding. No answer is final. This itself spells the pain of loss as a condition for growth. When I eventually went to Bere Island I had to disown the fairy-tale image I had formed earlier. There were family stories I heard later which undermined some of the prettier versions I had been given as a child. But in visiting it as an adult the enticing, magical beauty of Bere Island–like faith itself–has not been lost but developed. In a strangely similar way, through all of my life the mystery of Jesus continues its silent expansion.