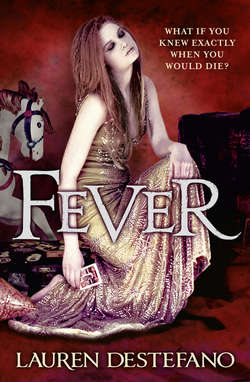

Читать книгу Fever - Lauren DeStefano - Страница 8

Оглавление

the tent, curled up so closely to the wall of the tent that its green tinges his skin. There’s a dingy blanket under him, and his shirt is gone.

Madame told me this is where I’ll rest tonight, while she figures out what to do with me. There’s a basin of water and some towels and soaps that look like they were hand-carved.

I wet a towel and dab at the red mark on Gabriel’s cheek. Tomorrow it will be just one of many bruises. He mutters something, draws a breath.

“Did I hurt you?” I say.

He shakes his head, nuzzles his face against the ground.

“Gabriel?” I whisper. “Wake up.” He doesn’t answer me this time, even when I turn him onto his back and wring cold water over his face. My heart is pounding with fear. “Gabriel. Look at me.”

He does, and his pupils are two small, startled dots in all that blue, and he’s scaring me. “What did they do to you?” I say. “What happened?”

“The purple girl,” he mumbles, smacking his lips and closing his eyes. “She had a … something.” He moves his arm as though in indication. And then he’s gone again. Shaking him does nothing.

“He’ll be out for a few hours.” One of the girls is standing at the tent’s entrance, a blanket bunched in her arms. “He seemed like he was in a lot of pain. I just gave him a little something to help. Here.” She offers me the blanket. “It’s fresh off the laundry line.”

She tries to help me cover him, but I shrug her away and snap, “You’ve helped enough, thanks. Whose fault is it that he was in pain to begin with?”

“Neither of you are from here,” the girl nonchalantly says, wringing a towel out over the basin. “Madame is very paranoid about spies. If I didn’t subdue him, she would have ordered the bodyguards to beat him unconscious. I was doing him a favor.” There’s no malice in the way she speaks. She hands me the wet towel, and she keeps a polite distance.

“What spies?” I ask, and gently rub away the sand and blood from Gabriel’s face and arms. I don’t like whatever is subduing him. He’s all I have in this terrible place, and he’s so far away.

“They don’t exist,” the girl says. “Most of what that woman says is nonsense. The opiates make her so paranoid.”

What have we stumbled into? At least this girl is not as nightmarish as the rest. Under all that makeup I can see the sympathy in her eyes that are two small dark stars in a nebula of green eyeliner. Her skin is dark. Her short hair is curled into glossy ringlets. And she, like everything here, carries that musty-sweet scent that radiates from everything Madame has touched.

“Why did he call you ‘the purple girl’?” I say.

“My name is Lilac,” she says, and indicates the light purple flowers on her faded dress, the strap of which keeps falling off her shoulder. “Ask for me if you need anything else, okay? I have to get back to work.”

She opens the tent flap, exposing the night sky and filling the tent with cold air and laughter, and the desperate grunts of men and the giggling of girls, and the steady rhythm of brass.

“This is my fault,” I whisper. I trace the line between Gabriel’s lips. “I’ll get us out of here. I promise.”

There’s salt crusted in my hair, and I feel so grimy that it’s tempting to climb into the basin to wash everything away. But whenever the bodyguards hear the water sloshing as I dip towels into it, they peer through the slit in the tent. Privacy is a lost practice in scarlet districts, I suppose. I settle for rolling up my sleeves and the legs of my jeans to wash as much as I can. Someone has laid out a silk dress for me—as green as this tent, with an orange dragon running up the side—but I don’t wear it.

I curl up beside Gabriel, fitting my arm around him. The soaps have left me with Madame’s strange scent, but he still smells of the ocean. I feel his skin moving under my fingers as he breathes, his muscles in constant, steady motion over his ribs. I close my eyes, pretend his is an ordinary sleep and that saying his name would bring him right back to me.

Time passes. Girls come and go. I pretend I am asleep and strain to hear what they’re whispering to each other. They say things I don’t understand. Angel’s blood. The new yellow. Dead greens. Men yell at them from a distance, and they go, their jewelry clattering like plastic shackles.

I feel myself falling asleep and try to fight it. But one minute I’m here, and the next I’m rocking on the glittering waves. One minute Gabriel is beside me, and then in the next, Linden is wrapping himself around me the way he did in sleep. He sobs in my ear and says his dead wife’s name, and I open my eyes. The hard dirt and thin blanket is an unwelcome change from the fluffy white comforter I was just hallucinating, and for a moment Gabriel seems strange. His bright brown hair nothing like Linden’s dark curls; his body thicker and less pale. I try rousing him again. No response.

I close my eyes, and this time I dream of snakes. Their hissing heads erupt from the dirt, and they coil around my ankles. They try to take off my shoes.

I wake in a panic. Lilac is kneeling at my feet, easing my socks off. “Didn’t mean to scare you,” she says. I feel like hours have passed, but I can see through the slit in the tent that it’s still nighttime.

“What are you doing?” My voice is hoarse. It’s so cold in this tent that I can see my own breath. I don’t know how these girls haven’t frozen to death in their flimsy dresses.

“These are soaked. You have to keep extremities warm, you know. You could get pneumonia.”

She’s right, I am freezing. She wraps my bare feet in towels. I watch her as she rummages through a small suitcase. Her curls are disheveled, her dress more rumpled. When she kneels by Gabriel this time, she’s got an array of things in a black handkerchief. She mixes powder and water in a spoon and takes a lighter to it until it bubbles, then draws it up into a syringe. Then she starts tying a strip of cloth around Gabriel’s arm above the elbow—which is something my parents used to do before administering emergency sedatives to hysterical lab patients—and that’s when I push her away. “Don’t.”

“It’s going to help him,” she says. “Keep him calm, keep you both out of trouble.”

I think of the warm toxins flowing through my blood after I was injured in the hurricane, how Vaughn threatened me and I couldn’t even muster the strength to open my eyes. How helpless and numb and terrified I was. I would rather have suffered the pain of my injuries, the broken bones, sprained limbs, stitched skin, than have been paralyzed.

“I don’t care,” I say. “You’re not giving him anything.”

She frowns. “Then, it’s going to be a rough night.”

I could laugh. “It already is.”

Lilac opens her mouth to say something else, but a noise at the tent’s entrance makes her turn her head. There’s a moment of fear in her eyes; maybe she thought it would be a man, but then she relaxes. “You know you’re supposed to stay hidden,” she says. “You want to piss Madame off?”

She’s talking to the child who has just crawled into the tent, not through the guarded entrance but through a small opening along the ground. Dark, stringy hair is covering her face. She moves more into the light, tilts her head to me, and her eyes are like marbled glass, so light they’re barely even the color blue—a startling contrast to her dark skin.

Lilac sets down the spoon and pushes the child back in the direction she came from, saying, “Hurry up. Get lost before we both get hell for it.”

The child goes, but not before pushing back and huffing indignantly through her nose.

Gabriel stirs, and I snap to attention. Lilac offers up the syringe again, gnawing her lip. I ignore it. “Gabriel?” My voice is very soft. I brush some hair from his face, and I realize how damp and clammy his forehead is. His face is splotchy with fever. His eyelashes flutter, but it’s like he can’t quite raise them.

Out in the night someone yelps in pain or maybe just aggravation, and Madame’s shrill voice cries, “Useless, filthy child!”

Lilac is on her feet the next instant, but she has left the syringe on the ground for me. “He’ll want it,” she tells me as she hurries for the exit. “He’ll need it.”

“Rhine?” Gabriel whispers. He’s the only one in this broken carnival who knows my name. He screamed it in the gale, pieces of Vaughn’s fake world whipping around us. He whispered it within the mansion’s walls, leaning close to me. He’s lured me from sleep that way, while my husband and sister wives slept before dawn. Always with such purpose, like it matters, like my name—like all of me—is a precious secret.

“Yes,” I say. “I’m right here.”

He doesn’t answer, and I think he’s lost consciousness again. I feel stranded, start to panic about him going back to that dark, unreachable place. But then he sucks in a hard breath and opens his eyes. His pupils are back to normal, no longer losing themselves in all that blue.

His teeth are chattering, and he’s stuttering and slurring when he asks, “What is this place?”

Not where, but what. “It doesn’t matter,” I say, blotting some sweat from his face with my sleeve. “I’m going to get us out of here.” We’re both lost here, but of the two of us I have a better understanding of the outside world. Surely I can figure something out.

He stares at me for a long while, shuddering from the cold and the aftereffects of whatever was in that first syringe. And then he says, “The guards were trying to take you away.”

“They took me,” I say. “They took both of us.”

I can see him fighting to stay awake. There’s a dark bruise forming on his cheek; his mouth is chapped and bleeding; he’s shaking so hard, I can feel it without touching him.

I wrap the blanket around him more snugly, trying to imitate the cocooning technique Cecily swaddled the baby with on a cold night. It was one of the few times she looked sure of what she was doing. “Rest,” I whisper. “I’ll be right here.”

He watches me for a long time, his eyes darting up and down the length of my face. I think he’s going to speak. I hope he will, even if it’s just to say this is all my fault, that he told me the world was dangerous. I don’t care. I just want him here with me. I want to hear his voice. But all he does is close his eyes, and then he’s gone again.

I manage a fitful sleep beside him, shivering, covered with only a damp towel so Gabriel can have all the covers. I dream of crisp bed linens; of sparkling gold champagne that warms my throat and stomach as it goes down; of category-three winds rattling the edges, revealing bits of darkness behind a shiny perfect world.

I’m ripped from sleep by a gurgling, retching sound that at first makes me think I’m at my oldest sister wife’s deathbed. But when I open my eyes, I see Gabriel doubled over in a far corner of our tent. The smell of vomit is not quite as overwhelming as all the smoke and perfume that keeps this place in a perpetual smog.

I hurry to his side, all earnest, heart pounding. And now that I’m close to him, I can smell and see the coppery blood coming from a gash between his shoulder blades; the skin tears as he tenses his muscles. I don’t remember there being any knives in the struggle, but we were ambushed so fast.

“Gabriel?” I touch his shoulder but can’t bring myself to look at the stuff he’s coughing up. When he’s finished, I offer him a rag, and he takes it, slumping back on his heels.

It seems stupid to ask if he’s all right, so I’m trying to get a good look at his eyes. Shades of purple are tiered under them, from dark to light. The cold is making clouds of his breath.

In the light of the swinging lantern, his own shadows dance behind his still form.

He says, “Where is this place?”

“We’re in a scarlet district along the coastline. They gave you something; I think it’s called angel’s blood.”

“It’s a sedative,” he says; his voice is slurred. He crawls back for the blanket and collapses facedown. “Housemaster Vaughn kept it in stock. Hospitals used to carry it, but they stopped because of the side effects.” He doesn’t resist as I position him onto his side and draw the blanket over him. He’s shivering. “Side effects?” I say.

“Hallucinations. Nightmares.”

I think of the warmth that spread through my veins after the hurricane, think of being unable to move; Vaughn only kept me conscious long enough to threaten me. And though I don’t remember it, Linden claimed I muttered horrible things while I dreamt.

“Can I do anything?” I say, tucking the blankets around his shoulders. “Are you thirsty?”

He reaches for me, and I let him draw me to his side. “I dreamt you’d drowned,” he says. “Our boat was burning and there was no shore.”

“Not possible,” I say. His lips are chapped and bloody against my forehead. “I’m an excellent swimmer.”

“It was dark,” he says. “All I could see was your hair, going under. I dove after you and realized I was chasing a jellyfish. You were nowhere.”

“I’ve been here,” I say. “You’re the one who’s been nowhere. I couldn’t wake you up.”

He raises the blanket like a wing, wrapping me inside with him. It’s warmer than I thought it would be, and I realize at once how much I’ve missed him while he’s been under. I close my eyes, breathe deep. But the smell of the ocean is gone from his skin. He smells like blood and Madame’s perfume, which lingers in the white soapy film that floats in all the water basins.

“Don’t leave me again,” I whisper. He doesn’t answer. I reposition myself in his arms and draw back to look at his face. His eyes are closed. “Gabriel?” I say.

“You’re dead,” he mumbles sleepily. “I watched you die”—his voice hitches with a yawn—“watched you die all those horrible deaths.”

“Wake up,” I tell him, and sit up, and pull the blankets away, hoping the sudden cold will shock him awake.

He opens his eyes, glossy like Jenna’s when she was dying. “They were cutting your throat,” he says. “You tried to scream, but you had no voice.”

“It’s not real,” I say. My heart is pounding with fear. My blood is cold. “You’re delirious. Look; I’m right here.” My fingers brush his neck, which is flush and warm. I remember when we kissed, Linden’s atlas between us; I remember the warm air of his little breaths on my tongue and chin and neck, the sudden draftiness when he drew back. Everything dissolved from around us in that moment, and I’d never felt so safe.

Now I worry that we’ll never be safe again. If we ever were.

The rest of the night is miserable. Gabriel succumbs to an unreachable sleep, and I fight to stay awake so I can keep watch against the dangers that lurk beyond our green tent.

When I sleep, I dream of smoke. Curling, twisting, weaving paths that lead nowhere.

“—up!” someone is saying. “Rise and shine, little love-bird! Réveille-toi!”

An arm tightens around me. I snap to attention. Madame is speaking in that phony accent again, her consonants flourishing like the smoke from her lips.

Daylight is a blinding force behind her, filling the silk outline of her scarves like rainbow lizard crests, making her face a shadow. And the whole tent is full of green, reflecting on my skin.

Sometime in the night Gabriel pulled me back into the blanket with him, and his arm is encircling my ribs. He buries his face in my hair, and I can feel the clamminess of his forehead. When I sit up, the movement doesn’t rouse him. He doesn’t regain consciousness at all.

The syringe. The syringe is no longer where Lilac left it.

Madame takes my hands and pulls me to my feet. She cups my face in her papery hands and smiles. “Even lovelier in the daylight, my Goldenrod.”

I’m not her Goldenrod. I’m not her anything. But she seems to have claimed me as one of her possessions, her antiques, her plastic gems.

I will Gabriel not to mutter my name again. I don’t want Madame to have it, rolling it off her tongue the way she fondled the flowers of my wedding band.

She pouts. “You do not want to wear the beautiful dress I laid out for you?” It hangs over her arm now like a deflated corpse, like the bloodless body of the girl who wore it last.

“Your sweater is so beautiful. How can you stand to wear it while it’s filthy?” she says sadly. I think her frown could melt right off her face. “One of the little ones will wash it for you.” Her accent has morphed to something else now. All of her THs come out like Zs, and her Ws like Vs. One of ze little ones vill vash it for you.

She thrusts the dress at me, and unwinds a fur stole from her shoulders and drapes it around my neck. “Change. I’ll wait for you outside. It’s a beautiful day!”

I’ll vait for you.

When she’s gone, I change quickly, figuring it’s my only way out of this tent. And I admit that the silk feels nice against my skin, and the stole, despite the choking must, is so warm I could get lost in it. Wearing these things may be the only way Madame lets me out of the tent, but what about Gabriel? Gabriel, who is still trapped in a haze. I kneel beside him and touch his forehead. I’m expecting it to be feverish, but it’s cold.

“I’ll get us out of here,” I say again. No matter that he can’t hear me; the words aren’t entirely for him.

Madame peels back the tent flap and tsk-tsks, snagging my wrist and tugging so hard, I think of the time my arm was dislocated and my brother had to snap it back into place. “Don’t worry about him,” she says. My bare feet are dragging, and I realize I’m not really trying to keep pace with her.

As we leave the tent, two small girls sweep past us and gather my rumpled clothes. Their heads are down, mouths tight. I only get a glimpse of them, but I think they’re twins. I’m pulled out into the cold sunshine, and the sky is a light candied blue, like I’m looking up through a sheet of ice. Madame fusses with my hair, which smells like a combination of salt water and a scarlet district. It feels heavy and tangled; her expression is distant, maybe disapproving, and I’m sure she’s going to criticize it, but she only says, “Don’t you worry about the boy.” She grins, and I swear I can see my outline repeated in each of her too-white teeth. “He’ll wake up when he can learn to be reasonable about sharing you.”

In the daylight, without the commotion or the light of the Ferris wheel, I can see what a wasteland this place is. Long stretches of just dirt, or a rusty piece of machinery erupting from the ground like it’s growing from a seed. There’s another ride off in the distance, and at first I think it’s a smaller Ferris wheel turned onto its side, but as we get closer, I can see metal horses inside of it, impaled by poles, their legs poised as though they were trying to escape before they were immobilized. Madame catches me staring and tells me it’s called a merry-go-round.

The black eyes of the horses fill me with pain. I want to break the spell on them, to animate the muscles in their legs and set them running free.

Madame brings me to the rainbow tent, the biggest and tallest of them all. Four of her boys are guarding it, their guns crossed at their chests like half an X. They don’t bother to look at me as Madame ushers me past, ruffling one of their heads.

She opens the tent flap, and a gust of cool air rolls in, unsettling the girls inside like wind chimes. They mutter and stir. Most of them are sleeping, piled against and atop one another.

The girls are all the same, like I’m looking into a house of mirrors. Long, bony limbs hunched against each other, and lipstick-smeared mouths full of rotted teeth. And for some girls it’s not lipstick—it’s blood. Unlit lanterns hang over their heads. The sun through the tent lights them up in oranges and greens and reds.

And farther down is the entryway to another tent that is veiled off by silk scarves trailing sickly sweet perfume, and something else. Decay and sweat. When Rose was dying, she concealed herself in powders and blush, but Jenna didn’t, and as I cared for Jenna during those final days, I could see her sallow skin beginning to bruise, and then the bruises would sink down to the bones and fester. It was a smell that haunted my dreams. My sister wife rotting from the inside out.

“I call this my greenhouse,” Madame says. “The girls sleep all day, so they can be fresh as daisies in the evening. Lazy girls.”

A few of the girls bother to look at me, blinking lazily and then returning to sleep.

She says she names the girls after colors, so she can keep track of them. Lilac is the only girl named for a color that is also a plant, because Jared, one of Madame’s best bodyguards, first found her lying unconscious in the lilac shrubs that border the vegetable gardens. “Belly about to burst,” Madame jokes, laughing maniacally. Lilac gave birth under a swinging lantern in the circus tent, surrounded by curious Reds and Blues. And the Greens, Jade and Celadon, who have since died of the virus.

“Nasty, useless little girl,” Madame Soleski says, indicating the little girl from last night with the strange eyes, who has crept out from a shadow. “One look at that shriveled leg and I knew on the day she was born that I’d never be able to get a decent price for her when she was the right age. But she can’t even be put to work! She scares the customers away. She bites them!”

Lilac, who is burrowed among the others, draws her daughter into her arms without opening her eyes. “Her name is Maddie,” she mutters, her voice slurred.

“Mad is right,” Madame Soleski says, nudging the child with her shoe. Maddie cants her head up at her with a violent stare. She snaps her little teeth at the old woman, venomous and defiant. “And she doesn’t speak!” Madame goes on. “Malformed. Horrible, horrible girl. She should be put down. Did you know that a hundred years ago when an animal was useless, they used to have a chemical that would put it to sleep forever?”

The smell of so many girls in such a small space is making me dizzy, and so are Madame’s words. One of the girls is twirling her hair, and it’s falling out in her hands.

A guard stands in the entryway. When nobody else is looking, I watch him reach into his pocket and then hold out a strawberry for Maddie. She pops it into her mouth, stem and all, a delicious secret she devours whole.

I hear a noise from the tent that’s veiled off. I think it’s a cough, or a groan. Either way, I don’t want to know. Madame is unfazed, and tightens her arm around my shoulders. I fight to keep my breathing even, but I want to cry out. I’m furious—maybe as furious as I was when I climbed out of the Gatherers’ van. I stood very still in a line with the other girls. I said nothing when I heard the first gunshot—the unwanted girls being murdered one at a time. There are so many of us, so many girls. The world wants us for our wombs or our bodies, or it doesn’t want us at all. It steals us, destroys us, piles us like dying cattle in circus tents and leaves us lying in filth and perfume until we’re wanted again.

I ran from that mansion because I wanted to be free. But there’s no such thing as free. There are only different and more horrible ways to be enslaved.

And I feel something I’ve never felt before. Anger at my parents for bringing my brother and me into this world. For leaving us to fend for ourselves.

Maddie stares at me, her eyes glassy and bizarre. This is the first time I’ve really looked at her. She’s obviously malformed—not just the strange, almost colorless blue of her eyes. In addition to her shriveled leg, one of her arms, the left, is shorter and much thinner than the other; her toes are almost nonexistent, as though something kept them from growing all the way out of her feet. But her face is angular and sharp, her expression all fearlessness and ire. It is the face of a girl who has seen the world, who realizes that it hates her, and who hates it in return.

Maybe that’s why she doesn’t speak. Why should she? What could she possibly have to say? She watches me, and then her eyes become distant, inaccessible, like she’s diving into waters too deep for me to follow her into.

Madame mutters something unkind and kicks the child in the shoulder, then she steers me outside.

There are plenty of other children, with stronger bodies and normal features. They work, polishing Madame’s fake jewels, doing laundry in metal basins and hanging it on wire that’s strung between dilapidated fences.

“My girls produce like jackrabbits.” Madame says the last word with malice. “Then they die and leave me to care for the mess they leave behind. But what can be done? The children make good workers at least.” Ze children.

Long ago President Guiltree did away with birth control. He’s of the pro-science mentality and thinks geneticists will fix the glitch in our DNA. In the meantime he feels it’s our responsibility to keep the human race alive. There are doctors who know how to terminate pregnancies, though they charge more than most can afford.

I wonder if my parents ever did it. For all the time they spent monitoring pregnancies, I’m sure they knew how to terminate one.

Abortions are supposed to be banned, but I’ve never heard of the president actually punishing anyone for disobeying one of his laws. I’m not entirely sure what the president even does. My brother says the presidency is a useless tradition that might have once served a purpose but has become nothing but formality—something to give us hope that order will be restored one day.

I hate President Guiltree, who has been in charge of this country longer than I’ve been alive. With his nine wives and fifteen children—all sons—he does not believe the end of humankind is near. He makes no move to stop the Gatherers from kidnapping brides, and encourages madmen like Vaughn to breed infants who will live their lives as experiments. Sometimes he’s on television, promoting new buildings or attending parties, flashing smiles, toasting his champagne glass at the TV like he expects us all to be celebrating with him. Or maybe he’s mocking us.

“He’s kind of handsome,” Cecily said once, when we were all watching TV and his face appeared in a commercial. Jenna said he looked like a child molester. We’d laughed about it then, but now that I’m in a scarlet district, Jenna’s former home, I think she must have been serious. Living in a place like this, she must have learned how to see all the monsters that can hide in a person.

Madame shows me her gardens, which are mostly patches of weeds and buds, encased in low wire fences. The strawberries, though, are growing under a weatherproof tarp. “You should see them in the spring sunshine,” she says giddily. “Strawberries and tomatoes and blueberries so fat they explode between your teeth.” I wonder where she gets the seeds. They’re so hard to come by in the city, where all of our fruits and vegetables seem to have taken on the city’s gray tinge.

She shows me the other tents, full of antique furniture, silk pillows piled on the dirt floors. Only the best for her customers, she says. The air in each of them is muggy with sweat. At the last tent, which is all pink, she turns to face me. She takes my hair from either side, in both hands, holding it out and watching the way it falls from her fingers. A strand gets caught on one of her rings, but I don’t flinch as it’s ripped from my scalp. “A girl like you is wasted as a bride.” She says the word like vasted. “A girl like you should have dozens of lovers.”

Her eyes are lost. She’s staring through me suddenly, and wherever she’s gone, it brings out the humanity in her. For the first time I can see her eyes under all that makeup, see that they’re brown and sad. And oddly familiar, though I’m sure I’ve never seen anyone like this woman in my life. I never even dared to peek into the shadows of scarlet districts nestled in alleyways back home.

I was never even curious.

Her lips curl into a smile, and it’s a kind smile. Her lipstick cracks, revealing a bleary pink underneath.

We’re standing by a heap of rusted scrap metal that is humming mechanically and emitting a faint yellow glow. One of Jared’s projects, I assume. Madame raves about his inventions. “Contraptions,” she calls them. “This will be a warming device for the soil. My Jared thinks it will make it easier to plant crops in the winter,” she tells me, patting one of the rusted pieces.

“So, what do you think of my carnival, chérie?” she asks. “The best in South Carolina.”

It amazes me how Madame can speak without the cigarette ever falling from the corner of her mouth. Maybe I’ve been breathing in too much of her smoke secondhand, but I’m in awe of her. Things fill with color as she moves past them. Her gardens grow. She created a strange dreamland with only the ghost of a dead society and some bits of broken machines.

She also never seems to sleep. Her girls are napping now that it’s daytime, and her bodyguards seem to alternate shifts, but she is forever weaving between tents, tilling, primping, barking orders. Even my dreams last night smelled of her.

“It’s not like any other place I’ve seen,” I admit, which is the truth. If Manhattan is reality, and the mansion a luxurious illusion, this place is a dilapidated, blurry line that divides the two places.

“You belong here,” she says. “Not with a husband. Not with a servant.” She wraps her arm around me, leading me through a patch of shriveled, snowy wildflowers. “Lovers are weapons, but love is a wound. That boy of yours,” she says, unaccented, “is a wound.”

“I never said I love him,” I say.

Madame smiles mischievously, her face flourishing with creases. It strikes me how the first generations are aging. Soon they’ll be gone. And no one will be left to know what old age looks like. Twenty-six and beyond will be a mystery.

“I’ve had many lovers,” she tells me. “But only one love. We had a child together. A beautiful little creature with hair that was every shade of yellow. Like yours.”

“What happened to them?” I ask, feeling brave. Madame has prodded and scrutinized me from the moment I arrived, and now, at last, she’s exposing her own weakness.

“Dead,” she says, picking up her accent again. The humanity vanishes from her eyes, leaving them reproachful and cold. “Murdered. Dead.”

She stops walking and tucks my hair behind my ears, tilts my chin, inspects my face. “And I am to blame for the pain. I should not have loved my daughter as I did. Not in this world in which nothing lives for long. You children are flies. You are roses. You multiply and die.”

I open my mouth, but no words come. What she says is horrible and true.

And then I wonder, does my brother think of me this way? We entered this world together, one after the other, beats in a pulse. But I will be first to leave it. That’s what I’ve been promised. When we were children, did he dare to imagine an empty space beside him where I then stood giggling, blowing soap bubbles through my fingers?

When I die, will he be sorry that he loved me? Sorry that we were twins?

Maybe he already is.

The tip of Madame’s cigarette flares red as she breathes deep. Lilac says the smoke makes her delusional, but I wonder how much of what Madame says is truth. “You are to be loved in moments. Illusions. That’s what I provide to my customers,” she says. “Your boy is greedy.”

Gabriel. When I left him, his dry lips were muttering silently. I noticed the stubble growing on his chin; he’d been re-dressed in his attendant’s shirt, which was ripped where the bodyguards had pulled at him. I was worried for the purple skin around his eyes, his raspy breaths.

“He loves you too much,” Madame says. “He loves you even in sleep.”

We walk through the strawberry patch, Madame prattling incessantly about the amazing Jared and his underground device that keeps the soil warm, simulating springtime so that her gardens can grow. “The most magical part,” she says, “is that it keeps the ground warm for the girls and for my customers.”

As she goes on, I think of what she said about Gabriel, about him loving me too much, but mostly about how he is a wound. Vaughn thought the same thing of Jenna; she served him no purpose, bore him no grandchildren, showed his son no real love, and she died for it.

It’s important to be useful in this world. The first generations seem to all agree about that.

“He’s a strong worker,” I say, interrupting her tangent about summer mosquitoes. “He can lift heavy things, and cook, and do just about anything.”

“But I cannot trust him,” Madame says. “What do I know about him? He was dropped at my feet as if from the sky.”

“But you are trusting me,” I say. “You’re telling me all of these things.”

She squeezes my shoulders, giggling like a bizarre and maniacal child. “I trust no one,” she says. “I am not trusting you. I am preparing you.”

“Preparing me?” I say.

As we walk, she rests her head on my shoulder, and her warm breath makes the hair on the back of my neck rise. The smoke from her cigarette is choking, and I suppress coughs.

“I do the best I can for my girls, but they are weary. Used up. You are perfect. I have been thinking, and I will not hand you over to my customers so they can reduce your value.”

Reduce my value. My stomach twists.

“Rather,” Madame says, “I think I could make more money off you if you remain pristine. We shall have to find a place for you. Dancing, maybe.” I can feel her smile without seeing her face. “Letting them have a taste. Letting them be hypnotized.”

I can’t follow the dark path her thoughts have taken, and I blurt out, “What about the boy I came with, then? If I’m doing all of this for your business”—the word gets caught on my tongue—“then I need to know that he’s okay. There needs to be a place for him.”

“Very well,” Madame says, suddenly bored. “It’s a small enough request. If he proves to be a spy, I will have him killed. Be sure to tell him that.”

By evening Madame sends me back to the green tent. I think it might have belonged to Jade and Celadon before the virus overtook them. She says one of her girls will be in to see me soon.

Gabriel is still out of it, and there’s a child holding his head in her lap. One of the blond twins I saw earlier.

“Please don’t be mad; I know I shouldn’t be here,” she says, not looking up. “He was making such awful noises. I didn’t want him to be alone.”

“What noises?” I ask, my voice gentle. I kneel beside him, and his skin is paler than before. There’s a rash of red across his cheeks and throat, and the skin around his bruise is fiery orange.

“Sick-person noises,” she whispers. Her hair is very blond. Her eyelashes are the same color, fluttering up and down like wisps of light. She’s running her small hands through his hair and across his face. “Did he give you that ring?” she asks me, nodding at my hand.

I don’t answer. I dip a towel into the basin, wring it out, and dab at Gabriel’s face with it. This feeling is horrible and familiar—watching someone I care for suffer, and having nothing but water to help them with.

“Someday I’ll have a ring that’s made of real gold too,” the girl says. “Someday I’ll be first wife. I know it. I have birthing hips.”

I’d laugh under less dire circumstances. “I knew a girl who grew up wanting to be a bride too,” I say.

She looks at me, and her green eyes are wide and intense. And for a second I think maybe this girl is right. She will grow up to be passionate and spirited; she will stand out in a line of dreary Gathered girls; a man will choose her, and come to her bed flushed with desire.

“Did she?” the girl asks. “Become a bride, I mean.”

“She was my sister wife,” I say. “And yes, she was given a gold ring too.”

The girl smiles, revealing a missing front tooth. Pale brown freckles dot her nose and spill into her cheeks like a blush.

“I bet she was pretty,” the girl says.

“She was. Is,” I correct myself. Cecily is gone from me, but she’s still alive. I can’t believe I almost forgot. It seems like forever ago that I left her screaming my name in a snowbank. I ran, didn’t look back, angrier with her than I’d ever been with anyone in my life.

The memory is a lifetime away from this smoky, dizzying place. I don’t even feel angry anymore. I don’t feel much of anything at all.

“How’s the patient?” Lilac says from the doorway. The girl whips to attention, and her expression turns sheepish. She’s been officially caught. She eases Gabriel’s head from her lap and hurries off, muttering apologies, calling herself a stupid girl.

“It’s her job to tend to the sickroom,” Lilac says. “She can’t resist a Prince Charming in distress.”

In the daylight, without makeup, Lilac is still a creature of beauty. Her eyes are sultry and sad, her smile languid, her hair messy and stiff on one side. Her skin, as dark as her eyes, is cloaked in gauzy blue scarves. Snow is flurrying around behind her.

She says, “Don’t worry. Your prince will be fine. Just a little sedated is all.”

“What have you given him?” I say, not hiding my anger.

“It’s just a little angel’s blood. The same stuff we take to help us sleep.”

“Sleep?” I growl. “He’s comatose.”

“Madame is wary of new boys,” Lilac says, not without compassion. She kneels beside me and presses her fingers to Gabriel’s throat. She’s silent as she monitors his pulse. Then she says, “She thinks they’re spies coming to take away her girls.”

“Yet she lets anyone with money come in and have their way with them.”

“Under strict supervision,” Lilac says pointedly. “If anyone tries something funny—and sometimes they do …” She makes a gun shape with her hands, points at me, shoots. “There’s a big incinerator behind the Ferris wheel where she burns the bodies. Jared rigged it from some old machinery.”

It’s not surprising. Cremation is the most popular way to dispose of bodies. We’re dropping off so quickly, there’s not even room to bury all of us, and there are some rumors that the virus contaminates the soil. And just as there are Gatherers to steal girls, there are cleaning crews who scoop up the discarded bodies from the side of the road and haul them to the city incinerators.

The thought makes me ache. I can feel Rowan, for just a moment actually feel him, looking for my body, worrying that I’ve already withered to ash. When the dust is heavy as he passes the incineration facilities, does he fear it’s me he’s breathing in? Bone or brain, or my eyes that are identical to his?

“You’re looking a little pale,” Lilac says. How can she tell? Everything in this tent is tinted green. “Don’t worry; we won’t be doing anything strenuous tonight.”

I don’t want to do anything but sit here with Gabriel, to protect him from another debilitating injection. But I know I have to play by the rules of Madame’s world if I hope to escape it. I’ve done it all before, I tell myself, and I can do it again. Trust is the strongest weapon.

Lilac smiles at me. It is a tired, pretty smile. “We’ll start with your hair, I think. It could stand to be washed. Then we’ll figure out a color scheme for your makeup. Your face makes a nice canvas. Has anyone ever told you that? You should see the messes I’ve had to work with before. The noses on some of these girls.”

I think of Deirdre, my little domestic, who called my face a canvas too. She was a wonder with colors; sometimes I would let her do my makeup if I was bored. Sensible earth tones for dinners with my husband; wild pinks and reds and whites when the roses were in bloom; blue and green and frosty silver when my hair was drenched with pool water and I sat in my bathrobe, reeking of chlorine.

“What is my makeup for?” I ask, though my stomach is twisting with dread.

“It’s just practice for now,” Lilac says. “We’ll do a few trials, show them to Her Highness.” She says the last two words without affection. “And whenever she approves a color scheme, we can begin training you.”

“Training me?”

Lilac straightens her back, pushing out her chest and mock-primping her hair; it pools between her fingers like liquid chocolate. She mimics Madame’s fake accent. “In the art of seduction, darling.” Ze art of zeduction.

Madame wants me to be one of her girls. She still wants to sell me to her customers, even if it’s not in the traditional sense.

I look at Gabriel. His lips have tightened. Can he hear what’s happening? Wake up! I want him to rescue me, the way he did in the hurricane. I want him to carry us both away. But I know he can’t. I’ve caused all of this, and now I’m on my own.