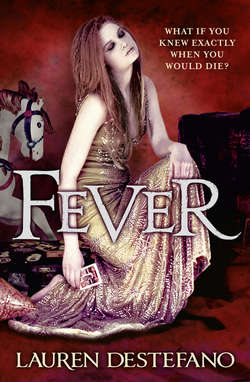

Читать книгу Fever - Lauren DeStefano - Страница 9

Оглавление

that droop down from the ceiling, so low our heads almost touch it as we stand before the mirror. The air is heavy with smoke; I’ve been exposed to it for so long now that my senses are not as offended. Lilac twists my hair into dozens of little braids and douses them with water, “to bring out the curls.”

Outside, the brass music has begun. Maddie is sitting at the entrance, peeking out into the night. I follow her gaze and catch the smooth white of a thigh, wisp of a dress. There are desperate, shuddering grunts and gasps. Lilac giggles as she smears lipstick onto my mouth. “That’s one of the Reds,” she says, “probably Scarlet. She wants the whole world to know she’s a whore.” She straightens her back, yells the word “Whore!” out into the night; it flies over Maddie, who is stuffing her mouth full of semi-rotten strawberries and watching. The girl outside yips and howls with laughter.

I want to ask why Lilac is okay with her daughter watching what’s going on out there, but I remember the teasing I got from my sister wives. They would undress while I was in the room, run into the hallway in their underwear and ask to borrow each other’s things. Late in her pregnancy Cecily didn’t even bother with the buttons of her nightgown, and her stomach floated in front of her everywhere. I guess being raised in such close quarters with so many other girls leaves no room for shyness.

And here, I am supposed to blend in. I can’t be shy. If Madame finds out that I lied about my torrid affairs, she won’t believe anything else about me. And so I act unfazed as Lilac explains Madame’s color-sorting system for her girls.

The Reds are Madame’s favorites: Scarlet and Coral have been with her since they were babies, and she lets them borrow her costume jewels. She lets them take hot baths and gives them the ripest strawberries from another little garden she grows behind the tent, because their bright eyes and long hair fetch the highest prices.

The Blues are her mysterious ones: Iris and Indigo and Sapphire and Sky. They cling to one another when they sleep, and they giggle at the things they whisper among themselves. But their teeth are murky and mostly missing, and they only get chosen by the men unwilling to pay for more, and they’re never in the back room for long. Men take them hurriedly, sometimes standing up, against trees, or even in the tent with all the others there to see.

There are more girls. More colors that blend together into one muddy mess as Lilac talks about them, pausing to ask Maddie to hand her the peroxide. Maddie, fingers and mouth stained red with strawberry juice, crawls (she hardly walks, I’ve noticed) to the assortment of jars and bottles and vials. She finds the one that’s labeled peroxide and offers it up.

“How did she know which bottle was the right one?” I say.

“She read it.” Lilac tilts the bottle onto a cloth, wipes some of the blush from my cheeks. “She’s very smart. ’Course, Her Highness”—again, said with malice—“likes to keep her hidden, thinks she’s just a useless malfie.”

“Malfie” is an unkind term for the genetically malformed. Sometimes women would give birth to malformed babies in the lab where my parents worked—children born blind, or deaf, or with any of an array of disfigurements. But more common were the children with strange eyes, who never spoke or reached the milestones the other children did, and whose behavior never synced with any genetic research. My mother once told me about a malformed boy who spent the nights wailing in terror over imaginary ghosts. And before my brother and I were born, our parents had a set of malformed twins; they had the same heterochromatic eyes—brown and blue—but they were blind, and they never spoke, and despite my parents’ best efforts they didn’t live past five years.

Malformed children are put to death in orphanages, because they’re considered leeches with no hope of ever caring for themselves. That’s if they don’t die on their own. But in labs they’re the perfect candidates for genetic analysis because nobody really knows what makes them tick.

“Madame said she bites the customers,” I say.

Lilac, holding an eyeliner pencil close to my face, throws her head back and laughs. The laugh mingles with the grunts and the brass and Madame shouting an order to one of her boys.

“Good,” she says.

In the distance Madame starts bellowing for Lilac, who rolls her eyes and grunts. “Drunk,” she mumbles, and licks her thumb and uses it to smudge the eyeliner on my eyelids. “I’ll be back. Don’t go anywhere.”

As if I could. I can hear the gun rattling in the guard’s holster just outside the entrance.

“Lilac!” Madame’s accented voice is slurred. “Where are you? Stupid girl.”

Lilac hurries off, muttering obscenities. Maddie follows her out, taking the bucket of semi-rotted strawberries with her.

I lie back on the bubblegum pink sheet that’s covering the ground and rest my head on one of the many throw pillows. This one is framed with orange beads. I think the smoke is to blame for my fatigue. I’m so tired here. My arms and legs feel so heavy. The colors, though, are twice as bright. The music twice as loud. The giggling, moaning, gasping girls are a music of their own. And I think there’s something magical about it all. Something that lures Madame’s customers in like fishermen to a lighthouse gleam. But it’s terrifying, too. Terrifying to be a girl in this place. Terrifying to be a girl in this world.

My eyes close. I wrap my arms around the pillow. I’m dressed in only a gold satin slip (gold has become Madame’s official color for her Goldenrod), but despite the winds outside, it’s warm in the tent. I suppose this is from the lingering smoke, and Jared’s underground heating system, and all the candles in the lanterns. Madame has truly thought of everything. To have her girls bundled in winter gear would hardly make them appealing to customers.

I’m eerily comfortable in this warmth. A nap seems incredibly inviting.

Don’t forget how you got here. Jenna’s voice. Don’t forget.

She and I are lying beside each other, surrounded by canopy netting. She’s not dead. Not while she’s tucked safely in my dreams.

Don’t forget.

I squeeze my eyelids down tight. I don’t want to think about the horrible way my oldest sister wife died. Her skin bruising and decaying. Her eyes glossing over. I just want to pretend she’s okay—just for a little longer.

But I can’t stave off the feeling that Jenna is trying to warn me to not be so comfortable in this dangerous place. I can smell the medicine and the decay of her deathbed. It gets stronger the more I feel myself fading to sleep.

The curtain swishes, clattering the beads that frame the entrance, and I snap to attention.

Gabriel is here, clear-eyed and standing on solid feet, dressed in a heavy black turtleneck and jeans and knit socks. The type of clothes Madame’s guards wear.

For a long moment we just stare at each other as if we’ve been apart for ages, which maybe we have. He has been beyond reach with angel’s blood since our arrival, and I have been whisked away by Madame at her every free moment.

I ask, “How are you feeling?” at the same time he says, “You look—”

I sit up in the sea of throw pillows, and he sits beside me, and the lanterns show me the deep bags under his eyes. When I left him this morning, Madame gave Lilac strict instructions to stop the angel’s blood, but he was sleeping, his mouth moving to make words I couldn’t understand. Now, at least, there’s color in his cheeks. His cheeks are flushed, actually. It’s especially warm in this tent, with all the incense sticks Lilac ignited, and the hot, sugary-sweet smell of the candles in the lanterns.

“How are you feeling?” I ask again.

“All right,” he says. “For a few minutes I was seeing strange things, but that’s passed now.” His hands are trembling slightly, and I put my hands over them. His skin is a little clammy, but nothing like it was as he lay comatose and shivering beside me. Just the memory makes me cling to him.

“I’m so sorry,” I whisper. “I haven’t come up with a plan to get us out yet, but I’ve bought us some time, I think. Madame wants me to perform.”

“Perform?” Gabriel says.

“I don’t know—something about dancing, maybe. It could be worse.”

He says nothing to that. We both know the type of performances the other girls put on.

“There has to be a way through the gate,” Gabriel whispers. “Or—”

“Shh. I think I heard something outside.”

We strain to listen for it, but the rustling I thought I heard doesn’t repeat itself. It could be the wind, or any of Madame’s girls flitting about.

Just in case, I move on to a safer topic. “How did you know I’d be here?”

“There was a little girl waiting for me to wake up. She handed me these clothes and told me to look for the red tent.”

I can’t help it. I wrap my arms around him and crush myself against him. “I was so worried.”

The response is a soft kiss against the hollow of my neck, his hands sweeping the hair over my shoulders. It has been too much to lie beside him every night, feeling a rag doll’s emptiness, to have the fragmented dreams of June Beans on silver trays and winding mansion hallways and hedge maze paths that took me no nearer to his presence.

Now I feel the full weight of him. And it’s making me greedy, making me tilt my head so that his kisses to my neck reach my lips, and making me take him with me as I lean back into the pillows that clatter with beads. A gemstone button is pressing into my back.

The smoke of the incense is alive. It traces the length of us. The heady perfume of it makes my eyes water, and I feel strange. Weary and flushed.

“Wait,” I say when Gabriel slides the strap of my slip down my shoulder. “Doesn’t this feel weird to you?”

“Weird?” He kisses me.

I swear the smoke has doubled.

There’s a rustling sound on the other side of the tent, and I bolt upright, startled. Gabriel blinks, his arm coiled around mine, sweat trickling from his dampened hair. Something has happened. Some kind of spell. Some supernatural pull. I’m certain this can be the only explanation. There’s the feeling of returning from someplace far.

Then I hear Madame’s unmistakable cackling. She pushes into the tent, clapping, her white smile floating in the smog. She’s saying something in broken-sounding French as she stomps on the incense sticks to extinguish them. “Merveilleux!” she cries. “Lilac, how many was that?”

Lilac slips into the tent, sorting through a wad of dollar bills. “Ten, Madame,” she says. “The rest complained they couldn’t see through the slit.”

Horrified, I hear male voices grumbling their disappointment on the other side of the tent. Amid a curtain of beads I can see a deliberate slit in the tent. I swallow a scream, cover myself by hugging a pink silk pillow to my chest.

Gabriel’s jaw tenses, and I put my hand on his knee, hoping it will quiet him. Whatever Madame was planning, we must play along.

“Aphrodisiacs are quite potent, aren’t they?” Madame says, reaching into a lantern and snuffing the flame with her finger and thumb. “Yes, you put on quite a show.” She’s looking at me when she adds, “Men will pay great money to see what they can’t touch.”