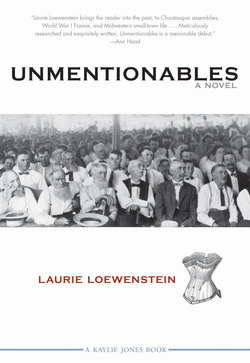

Читать книгу Unmentionables - Laurie Loewenstein - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FIVE

WALL DOG

FROM THE COMMUNITY BOOTH just beyond the ticket stand, Helen surveyed the track of beaten grass running across the Chautauqua grounds. Although it was two hours before the evening’s performance, a few determined old folks were already marching toward the tent. As they passed the stall, none so much as glanced at the Equal Suffrage Club pamphlets she had artfully fanned across the table. Use of the community booth rotated among various Emporia organizations. Yesterday, it had been the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Tonight, Emporia’s modern women, the suffragists, had their chance to bend the public’s ear.

A bee circled the bouquet of Queen Anne’s lace intended to pretty up what some might consider dry piles of literature. Helen stood to swat it away. She sat down again, adjusting the white and yellow suffrage ribbon pinned at her shoulder, her shoe absently knocking against the table leg. The WCTU had left behind a box of temperance song books. She flipped through one. Tried humming “Ohio’s Going Dry” to the suggested tune of “Bringing in the Sheaves.”

“Looks like you’ve got some instructive reading there.” Louie, the painter from the scaffolding outside her office window, was leaning against the tent pole on one side of the booth. He had changed from work overalls into flannel trousers and a suit coat. There was a change in his gaze too, which seemed less forward, more thoughtful.

“I’m just passing the time before the crowds arrive.”

“Looks like you might have awhile to wait.”

“I’ll get some takers.” Helen resecured a tassel of hair that had come loose from her topknot.

Louie picked up one of the brochures, glanced at it, and tucked it in his pocket. “I think you might have gotten the wrong impression of me. I take these sign painting jobs every summer. Puts food on the table the rest of the year.”

“Oh, really?” Helen said coolly.

“Yes, really. I’m an artist.”

Helen sat up a little straighter. “That so?”

“I took courses at the Art Institute up in Chicago. Even won first place in a student exhibition.”

A farm family passed, mother in the lead, followed by a weary-looking fellow with a sack coat slung over his shoulder and five dark-haired children.

Helen pushed the pamphlets around. “What do you paint? Landscapes?”

Louie threw a leg over the corner of the table. “Used to, but now I’m a cubist.”

Helen’s brows raised. “I’ve no idea what that is.”

“It’s revolutionary is what it is. Take a walk with me around town, and I’ll tell you all about it.”

“I can’t. I’m the only one here.” She motioned to the single wooden chair.

“I don’t think anybody’s going to miss you,” Louie said. “But okay. How about when the program starts?”

Helen hesitated. “Revolutionary? How so?”

“Give me an hour and I’ll bring you up-to-date on the most advanced, modern movement in the art world since—since I don’t know what.”

The initial trickle of patrons had grown into a crowd. Not far away, Helen thought she glimpsed her stepfather’s boater bobbing her way. “All right. I’ll meet you under those elms at the edge of the grounds in twenty minutes,” she said hurriedly. Louie saluted and sauntered off.

As Deuce’s hat drew closer, the throng parted. Marian, seated in an ancient wicker wheelchair, emerged feet first. Then came the tip of a cane, which she was sweeping back and forth. “Coming through!” she called out. Deuce’s face was flushed and sweat bloomed under his arms as he propelled the wheelchair across the bumpy pasture. Marian’s healthy foot tapped impatiently on the footrest, her mouth determined, her free hand scooting along the rubber wheels to speed up the motion.

When she spotted Helen her face brightened. She waved the cane at the banner over the booth. “Working for the cause!” she cried.

Helen rushed around the table of pamphlets.

“Goodness, Papa, you didn’t shove her all the way from Tula’s on this bumpy ground?”

Marian jumped in. “Oh, no. He pulled the motorcar as close as he could to the ticket booth.”

Deuce fanned his face with his boater. “Really, it was no problem.”

“You know, I think I could just use this cane.” Marian started to push herself up out of the chair. “I just hate being carted around like a sack of—”

Deuce pushed her shoulder down firmly, rolling his eyes at Helen. “I have strict orders from Tula that you’re to stay in the wheelchair, remember?”

“Where is Tula?” Helen asked.

“Up at the Bellmans’. Jeannette’s better and Hazel was finally willing to let someone else take over the nursing and get some sleep,” Deuce explained.

“Thank goodness,” Helen said.

Marian nodded. “Yes, it’s tremendous news. Didn’t I tell Dr. Jack she’d come around?”

“Speaking of Dr. Jack . . .” Deuce began.

A surge of ticket holders was making its way toward the tent. A loosely strung youth with wrists well clear of his cuffs tripped over Marian’s back wheel. “Sorry, ma’am,” he mumbled, lifting his hat.

“Slow down, son,” Deuce said as he steered the bulky wheelchair out the stream of traffic.

“I just hate feeling like someone’s old granny.” Marian thumped the wicker armrest. “But the good news is that the doctor says it’s only a sprain.”

A pair of elderly sisters passed behind Deuce, murmuring to one another. “Such a pity about the Bellman . . .” They glared at Marian.

Deuce, unaware of the exchange behind his back, was fidgeting with his boater, rotating it through his fingers as if crimping a piecrust. He spoke up: “I’d like to check in with Dr. Jack. See if he’s treated any more typhoid cases. Seems to me like there’s fewer coming down with it. Has he passed by here, by any chance?”

Helen shook her head.

Marian continued with her train of thought: “Anyway, Deuce has been very kind to push me around in this contraption. I thought I’d go stir-crazy if I stayed cooped up in that sleeping porch any longer. But really,” she turned to Deuce, and handed him his suit jacket that had been draped across her lap,“I’m sure Helen and I can manage from here.”

Looking relieved, Deuce said, “Yes, I really need an update from the doc. You can get Marian inside, Helen?”

Helen’s first impulse was to shout out, Of course! Here was the chance to talk with a famous suffragette, but . . . she hesitated. Her mind leaped to Louie and something stirred inside, tugging her away from Marian and toward the darkening trees at the edge of the grounds.

“I don’t know if I can, you know, leave the booth. But I’m sure—”

“Of course not,” Marian broke in. “You’re doing important work. Deuce can commandeer someone. How about the fellow over there? This is just too frustrating. I don’t know why I can’t use this cane.”

“No, no. Let me get you inside right now and I’ll track down Dr. Jack later,” Deuce said in what Helen recognized as his polite, out-in-public voice.

* * *

A few stragglers trotted past and then Louie and Helen were alone under the elms, the shadows vibrating with the rhythmic creak of late-summer crickets. Louie took her hand. For a short while they walked in silence. Everyone, except the very ancient or very sick, was at Chautauqua and the streets were quiet under the old trees. Ahead, twin rows of streetlamps shone along State Street.

“So, what’s a cubist?”

“You heard of the Spaniard Picasso?”

Helen twisted her lips to one side. “Maybe.”

“Okay. How about the Armory Show a couple of years back?”

“The one that was so controversial?”

“It started out in New York, then came to Chicago. I saw it and it changed my life. Changed my whole way of thinking. Before that exhibit, I was doing landscapes, snow in the woods, that sort of thing.” Louie paused to light a cigar. A house cat silently descended some porch steps across the street and melted into the bushes.

“But now, whole different ball game.” He made an expansive motion with his hands, fingers wide. An odor of turpentine eddied from his jacket.

“This way?” he asked, taking Helen’s arm and pointing up the street with the cigar.

“Sure. Fine. All the streets end up in the same place anyway. Go on.”

“So, in cubism, you think about something you might paint such as, say, someone’s face. Your face, let’s say. But instead of trying to get it to look as much like you as possible, like a mirror image, I take the pieces apart.”

Helen raised her brows.

“The face is made up of all different pieces, right? Eyes, nose, mouth, nostrils, all that. And also, when I look at your chin, say, from this direction . . .” They were under a streetlight. Louie grasped her chin and tipped it to the left. “. . . I see it one way. But when I do this,” he continued, pulling her face to the right, “it looks different. And when I do this . . .” He bent toward her, pressing his lips against hers. After a moment he said, “And when I do that, I don’t see your chin but I feel it.”

Helen pulled back, her eyes narrowed. “That just seemed like an excuse to kiss me.”

Louie threw up his hands. “Not at all! Just trying to bring some of the world of modern art to the culturally impoverished.”

“Now you’re making fun of me,” she laughed, thumping her handbag across his shoulders.

He grinned. “Just saying maybe you should get out more. Visit Chicago.”

“I have,” she said smartly. “And I’m moving there.”

“Terrific. This is my last job of the summer. I’m heading back to Chicago in a couple of days. I’ll take you to the Art Institute, give you some education.”

“You really don’t give up, do you? But it won’t be until next year.”

“Next year? Can’t you make it sooner?”

Helen flung a hand up. “Too complicated.” Inside, her mind was busy: Why not now? She was not going to change her mind even if Grandfather Knapp made her wait ten years.

“Say, what’s over here?” Louie was saying. He took her hand and pulled her toward a stone building flanked by wide granite steps.

“It’s First Baptist. My friend Mildred goes here.” Helen allowed herself to be led down a shadowy concrete walkway along the side of the church.

“Is that so?” he said absentmindedly, as if he wasn’t really listening. “What’s in here, do you think?”

Helen started to answer and then realized that Louie wasn’t really asking her a question. He pulled her under the small portico of a side door and put an arm around her waist. Helen glanced fleetingly over his shoulder at Reverend Carlisle’s manse next to the church. None of the lamps were lit. Louie’s other hand hung at his side, pinching the burning cigar.

“Put that out,” she said and he immediately dropped it. The cigar emitted a small shower of sparks before it was ground out by his shoe. She put both her arms around his neck and, when he kissed her, his lips were pleasantly moist and firm.

After a few more kisses, Helen pulled him out from the doorway. “Let’s keep walking.”

They turned left onto State Street, passing a stray dog with a wiry coat who trotted by purposefully. A display in the sporting goods shop caught Louie’s eye and he spent some time talking about the athletic prowess required to work scaffolding, as he examined the fishing hampers, golf bags, and medicine balls.

At the corner of Main and State, he stopped to light another cigar.

“How old are you?” Helen asked.

“Twenty-seven. That okay?”

“Yes.”

“So, your daddy’s a big shot in town,” he said, leaning against a streetlamp.

“Stepfather. Sort of. But it’s more my grandfather. He’s president of the savings and loan.”

They took a different route back toward the Chautauqua grounds. When the brick belfry of the United Methodist Church came into view, it was Helen who pulled Louie around the rear and down into an open basement stairwell. This time, after kissing her lips a number of times, he pressed his mouth to her temples, the space between her brows, and the tender spot just below her jaw where her pulse fluttered. She looked up at the rectangle of sky visible from the stairwell as he unbuttoned her shirtwaist. There were no stars visible, only a skim of clouds hanging in the warm night air.

Louie had smoothly freed her four top buttons and Helen felt his fingertips skimming her bare right shoulder in brushlike strokes. The sensation was dizzying, as if a cord below her belly, from deep within, was vibrating until her entire body thrummed.

“Did you say something?” Louie breathed into her ear. His fingers scooped inside her shirt.

“I need to get back to the tent before the program’s over,” Helen said, stepping away and securing her buttons. He protested, but she was already halfway up the stairs.

At the top she glanced at her watch and judged it would be about an hour before the Mystic Entertainer reached his grand finale. There were, she knew, at least two more churches between United Methodist and the Chautauqua grounds, and she meant to stop at each.