Читать книгу Unmentionables - Laurie Loewenstein - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

SIGNS AND SYMBOLS

THE NEXT MORNING, DEUCE WOKE to the buzzy rattle of the alarm clock. He reached across to turn it off. For the past two years, during sleep, the memory of his wife Winnie’s passing would somehow be erased from his mind, and the empty space beside him was always a shock in the dawn’s light. But this morning, even before he opened his eyes, he knew that she was not there.

For a few minutes he sat dull-eyed on the edge of the bed, his mind wooled in sleep. Absently, he thumped his feet against the rag rug and rubbed his knees. Below the open window, the floorboards were wet where it had rained in.

He switched off the rotating fan and shuffled to the bathroom. Even at this hour, the air was stuffy. A wrinkled sash hung from the newel post. In the bathroom, the mat was soggy. A hairpin stuck to the damp skin of his heel. Helen must have been running late for work.

As he dabbed shaving soap to his cheeks, Deuce thought of Helen’s graduation day. It had been stifling on that day too. Helen had led her class across the lawn, up the aisle between rows of applauding families, and onto the bunting-draped outdoor dais. As valedictorian, she had taken her seat in the first row at the front of the stage, Deuce watching with amusement as her foot jiggled impatiently through Reverend Sieve’s invocation, Miss Thayer’s salutation, and the class history. Then it was her turn at the podium.

She had begun in the accepted manner, with references to “life’s path,” “beginnings, not endings,” and “realizing our possibilities.” She carried on for a good ten minutes in this fashion before veering abruptly into virgin territory. Deuce had straightened, suddenly alert.

“But these really are just platitudes, at least for the female members of our graduating class who are still denied full participation as citizens, as workers, even as we step forward to aid our nation in a time of war. Yes, we are fortunate to live in Illinois, a state where women have at least been granted limited voting rights, but none of us can earn a wage equal to a man’s, or enter into marriage on equal footing.”

A gust tossed the blue and yellow bunting. Miss Thayer and several of the young ladies clamped their hats to their heads. Hatless and unheeding, Helen continued.

“That is why tomorrow, when the 7:20 for Chicago pulls out, I’ll be boarding it. The suffrage movement needs soldiers too, and I intend to join up. And I challenge each of the members of our class to join with me and journey out into the wider world.”

Abruptly, she took her seat. Father Knapp gripped Deuce’s arm.

“What the hell is she talking about?” he asked, in a barely controlled whisper. “Did you know about this?”

Deuce’s mouth went dry. All spring Helen had chattered on about the Chicago Women’s Political Equality League, the city’s abundance of jobs for women, its profusion of respectable rooming houses. He knew she was going to go sometime, but he didn’t think she’d be leaving so soon.

“Well?” the old man tightened his grip. Reverend Sieve, head bowed, was muttering the benediction.

“She’s talked about it some,” Deuce said. “I didn’t take it seriously.”

“There is no way in hell she’s going,” Father Knapp growled.

“No, of course not.”

Helen rushed up to the two men, cheeks and eyes radiant. “How did I do?”

Deuce quickly turned away from his father-in-law. “You were wonderful, sweetie.” He wrapped his arms around her. “Great day.”

Helen laughed, pulled back, and gave Father Knapp a solemn peck on the cheek. His expression was as stiff as his old-fashioned collar. She glanced at Deuce with raised brows.

“Your grandfather—”

Father Knapp interrupted. “There is no way in hell you’re going to Chicago.”

“But—”

“And you did nothing but embarrass yourself up there.” He flung his hand toward the stage. “Disgraced me too, and the memory of your mother.”

When her grandfather mentioned Winnie, Helen’s cheeks paled. The old man had struck a nerve. Although outspoken, Helen’s vulnerability lay in wanting to live up to Winnie’s aspirations for her. The old man knew this and, in the two years since Winnie’s death, used his late daughter’s memory to manipulate his granddaughter. Deuce hated him for this. From the day he’d exchanged vows with Winnie, with a somber two-year-old Helen looking on, the old man had done nothing but stage manage every part of their lives.

“Look, it’s too soon. Come work at the Clarion for a year, just like we discussed. Then the three of us can sit down and, you know, reconsider, and then . . .”

Helen glared directly into Deuce’s eyes. “That’s the kind of thing you always say. You’re always compromising. You go along with everybody. Well, sometimes that doesn’t work. You have to take a side.”

She turned and stomped off across the wide lawn, her graduation gown billowing behind her.

Deuce started to follow but Father Knapp pulled him back. “Let her go. She’ll cool down. She’s got to learn that she’s not going to always get her own way.”

* * *

Remembering this exchange, Deuce wriggled uncomfortably as the razor scraped his left cheek. Even now, three months later, with Helen somewhat resignedly installed as bookkeeper at the Clarion, he knew things weren’t settled. She could take off at any minute. Probably the only thing keeping her was Father Knapp’s crack about Winnie turning over in her grave.

Yet, deep down, he was a tiny bit glad if it meant she’d stay. The house was too big for one person. Already, with Winnie gone, at least half of the rooms had gone fallow. On his rare visits to the parlor, the draperies smelled stale, his footsteps echoed on the parquet floor. What would living here be like when it was just himself?

He knew in his heart he should let her go. Help her go. But banging up against his father-in-law’s opposition was dicey. The man had bought and furnished Deuce and Winnie’s house, paid for Helen’s painting, piano, and horseback riding lessons—none of which were within the reach of a newspaperman—and, most importantly, Father Knapp was a silent partner—the majority partner—in the Clarion. But Deuce loved Helen more than anything and refused to squash her dreams. The evening of the graduation ceremony, he and Helen had talked it through. She apologized for what she’d said and he admitted that he allowed himself to be swayed too often. Although unhappy these last three months, she’d agreed to stay in Emporia for one more year.

The metal clatter of the trolley’s steel wheels on the tracks out front pulled Deuce’s thoughts back to the steamy bathroom and the lather drying on his face.

In the bedroom, he dropped a hand towel onto the wet floorboards by the window. Over at the Lakes’, the porch shades were drawn. Tula’s houseguest must be sleeping in. He fingered the tangle of ties on the closet doorknob. Two striped affairs, some muted solids, and the lavender number that Helen had given him for his birthday five years back. He’d worn it once but the fellows at the barbershop had razzed him and that had been the end of it. “Don’t want to stick out like a sore thumb,” he’d mumbled to Winnie when Helen was out of earshot. Today he felt differently and yanked it off the rack with a snap.

On the dresser, a tortoise box held enamel lapel tacks and gilt watch fobs representing most of Emporia’s fraternal orders and business clubs. Becoming a member of the Elks, Knights of Pythias, the Commerce Club, and all the others represented Deuce’s slow but steady crawl up the social ladder.

Since the 1820s, when his ancestors first settled in what was to become Macomb County, there had been rumors about colored blood in the family. No Garland ever publicly confirmed it, but when he was nine, Deuce had been ushered into his grandfather’s sick room. There, the old man, with skin the color of fallen oak leaves, solemnly explained that way back, Deuce’s great-great-great-grandfather had married a Negress and it was a disgrace that haunted the Garland clan to this day. “But don’t never admit it, boy. They can say what they like, but they can’t prove it.” Even without confirmation, whispers clung like cobwebs to each generation and Deuce never completely shook off the humiliation he’d felt as a small boy, teased in the schoolyard with shouts of “Nigger Deuce.”

The taunts boiled up like welts whenever trifling disputes arose. As a child, it had happened over games of mumblety-peg and duck, duck, goose and he’d run home to the comfort of his older sisters. Later, the insult was occasionally flung during poker games and, more often, in disputes over the attentions of young ladies. Wounded, he had retreated to the type cases of Brown’s Print Shop, where he’d worked as an apprentice. As he grew older, Deuce adopted a different strategy: rather than retreating, he’d moved heaven and earth to fit in. He took up the cornet when silver bands were the rage; ordered roast beef and mashed, same as all the regulars at The Rainbow Grill. When asked what he thought about a matter, he blew words as slippery and vague as soap bubbles until the questioner revealed his opinions first. “You got that right,” was his pat response. None of this was all that difficult because he had a naturally pliant nature. It was his heart’s desire to belong. He wanted nothing more than to be included. His nickname, Deuce, came from his earliest years when he ran after his older siblings shouting, “Me too, me too!” His first nickname was Two-Two, and eventually it became Deuce.

And what were the Elks and the Knights of Pythias and the others about, if not belonging? The handshakes, the toasts, the rituals, all separated insiders from outsiders. Then there were the levels, ranks, and orders to rise through, each with its own signifier worn on the lapel for all to see; recognition made tangible in bits of brass and gilt. He’d worked like a dog to win acceptance. But more and more, since Winnie’s death, he yearned to rise above being nothing more than the mouthpiece for Emporia’s prominent and powerful. Now, with the typhoid deaths, this urge became more acute.

He fastened on the usual array of pins and headed downstairs. Lifting the cake cover, he found a day-old biscuit. Breaking it open with his thumbs, he spooned on strawberry jam and reassembled the two halves. Bundling his breakfast in a napkin and dropping it into his pocket, something Winnie would never have allowed, Deuce retrieved his boater from the hall table and settled it on his head. He caught sight of himself in the hall mirror. Something prompted him to skew the hat to the left. He walked out of the house, letting the screen door bang behind him.

Deuce’s two-story house, with its cedar shakes painted forest green and a wide-columned porch was considered substantial by Emporia standards. Three hoary chestnuts shaded the front lawn and a narrow strip of concrete led from the porch to the sidewalk. To one side was an open lot, waiting for Emporia’s steady progress in the form of another solid middle-class manse.

On the other side, one step closer to town, was the Lakes’ boxy four-square with its coat of whitewash where the never-married Tula kept house for her brother Clay. Devoid of trim work and shutters, its shallow porch and four rooms per floor held a certain charm for townspeople who were nostalgic for the rural life. It brought to mind Emporia’s farming roots when this shady street, now grandly renamed Mount Vernon Boulevard, had been known simply as Route 7 and was used by farmers, like Deuce’s grandfather, to bring crops to town. Even now, a cornstalk sometimes sprang up between the brick paving stones as long-dormant kernels, dropped from wagons, made up their minds to germinate.

Deuce’s father had left the farm but not gone far, just six miles into town, to clerk for the railroad. But every summer he sent Deuce’s older sisters out to Grandpa’s. Deuce was the youngest of six, the only boy. He was still a toddler when the two oldest caught typhoid out at the homestead. The undertaker’s wagon carried them back into town, along this very street.

He gazed abstractly down the embowered boulevard. Maybe I’ll telegram the Springfield editor today and get permission to reprint that piece on adulterated milk. But his courage wavered when he thought of angering his advertisers and his father-in-law.

At the fork, where Mount Vernon slanted eastward, Deuce veered onto State, with its closely packed row of storefronts. A stranger in gray pinstripes, aggressively employing a toothpick to his molars, was lounging in the doorway leading to the second-floor photography studio owned by Tula’s brother Clay. There was something unsavory about the man’s stubbled cheeks. Deuce considered questioning the fellow about what his business was, when a voice from behind broke through his thoughts and the stranger was forgotten.

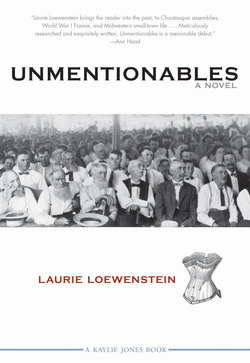

“Sure looks fine,” Alvin Harp, the garage owner, was saying, pointing to the canvas banner slung across the street, shouting, Chautauqua Week, August 12-19, in a fancy font.

Deuce grinned. “Surely does. Emporia has done herself proud.”

“Those too.” Alvin gestured with his chin toward the red and yellow placards in the window of Fitzer’s Market.

A wagon bumped down the street pulled by two mules. A lanky farmer with shirtsleeves rolled up held the reins beside his straight-backed wife in her best Sunday dress. In the back, four youngsters gripped the sides, ogling the store windows.

Deuce said, “I’d say Chautauqua is just about the best thing to ever happen here. First of all, it brings the farm and town folk together, and then there’s the educational . . .”

His voice continued, but Alvin’s gaze drifted past Deuce’s shoulder to a lanky Negro in overalls walking toward them. Everyone called the man, who was a janitor at the depot, Smitty. As Smitty approached, Deuce’s editorializing ran out of steam. He pulled a watch out of his vest saying, “Better get to the typewriter.” Alvin smirked, anticipating what was to come. Deuce was turning toward the Clarion when he caught sight of the colored man.

“Oh, uh, think I’ll go over to the post office first, though, and make sure Helen picked up the mail. See you tonight in the tent,” Deuce called over his shoulder. He hurried across the street, scarlet staining his cheeks. Alvin and everyone in town knew the rumors of Deuce’s family history and those who were mean-spirited got a laugh over the excuses Deuce came up with to avoid crossing paths with the town’s colored population. Alvin ambled off to the garage with a grin.

The newspaper building was owned by Father Knapp who believed in maximizing his investments whenever possible. Its exposed north wall faced a busy cross street. Over the years, Knapp had leased the wall to a succession of national concerns—Tiger Head Malt Syrup, Sweetheart Bread, and Coca-Cola—to use as a sign board. This went against the grain for Deuce, who believed that local products should command the town’s allegiance. But asking Father Knapp to take a smaller profit was out of the question.

The painted Coca-Cola advertisement had been shucking off the building’s raw bricks for a couple of months. Turning the corner, Deuce saw that was about to change. A sign painter and his helper were noisily hoisting a plank and themselves up the side of the building with rusted pulleys. Upon learning from the men that the new ad would be for U-Needa Biscuits, another big-time outfit, he threw the front door open with a bang.

“Morning, fellas,” he called gruffly to the two young salesmen hunched at desks behind the counter. He took the iron stairs two at a time up to the newsroom. By the time he reached the top, he’d cooled down a little. The room was already thick with cigar smoke that clung like bacon grease to the rows of desks and stacks of old editions. Helen was at her place in the far corner. A potted geranium occupied her side-facing window that was now festooned with scaffolding ropes. The first time he’d laid eyes on Helen, Deuce was working at the print shop. Winnie Richards, as she was known then, came in to order calling cards. She’d recently moved to Emporia from Chicago with her father, George Knapp, the town’s local-boy-made-good, and her young daughter, Helen. Her father let it be known that Winnie had been married to an up-and-coming banker who died of yellow fever when Helen was only three months old. The alternate version, passed around the town’s watering holes and sewing clubs, was that the baby’s father was the son of a prominent family, but had a drinking problem and was crushed to death by a train when he’d passed out on some railroad tracks. Deuce was behind the print shop counter when Winnie entered with Helen, a toddler wearing a frilly cap and a serious expression. Something about the little girl’s grave brows contrasted with the silly bonnet had captivated him.

Smiling at this long-ago memory, Deuce approached her desk. “You’re an early bird.”

She lifted her head from the open accounts book. “Remember? I’m leaving at three to set up the women’s booth at Chautauqua?”

“Oh, yes, yes.”

Jupiter, the office dog, emerged stiffly from under Helen’s desk. He made a show of rearing back to stretch his front legs before shoving his narrow snout into Deuce’s palm.

“Any word on Mrs. Elliot Adams? Did she break anything?” Helen asked.

Deuce shrugged. “Things were still buttoned up tight when I passed Tula’s just now.”

Helen frowned at the ledger and erased an offending entry. “You should check on her. Include it in the article.” She brushed crumbs of rubber onto the floor.

He pointed at her and snapped his fingers. “Good idea.” He turned on his heel.

Helen nodded approvingly. One of the positives, the only positive, about remaining in town, was her role in nudging Deuce toward making the Clarion a real newspaper.

A volley of clattering sounded outside her window and she saw a pair of muscular hands pulling hard on a scaffolding rope. The rope was threaded through two pulleys that squealed in protest as they were set into jerky motion. A shock of black hair appeared above the sill—with another screech, the head and upper torso of a young man in white painter’s coveralls. His thick hair needed trimming and his eyes were squinty—like one of N.C. Wyeth’s sunburned pirates on the plates in Treasure Island. From the other end of the plank, a voice shouted, “That’s it!” and the young man tied off the rope. Helen was staring when he suddenly turned and grinned, displaying brilliant white teeth against tan skin.

“Hello there,” he said. “Admiring the view?”

“No. I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Helen answered, her words clipped.

“Well, I’m enjoying the scenery, and I’m not talking about out there,” the painter said, poking his thumb toward the buildings in back of him. He grinned again and his ears rose slightly. “Guess we’re going to be neighbors for a day or two. I’m Louie Ivey.”

Helen smiled tightly and busily began ruling off a ledger column.

“I think it’s the polite thing to tell me your name, don’t you—?”

He was interrupted by the gruff voice from the other end of the scaffold. “Hey, Louie, quit your gabbing and get started before the brushes dry out.”

Louie cocked his head at his unseen partner. “Guess it’s time to get to it.”

“It’s Helen,” she said quickly. “My name’s Helen Garland.”

“Nice to meet you, Miss Garland. Guess I’ll see you around—ha ha,” he said loudly.

Smart aleck, Helen thought as she shuffled the Clarion’s July bills into chronological order. Still, she couldn’t help looking up one more time as Louie, now with paintbrush in hand, began swabbing above her window, the bristles making a persistent scratching sound against the rough brick.