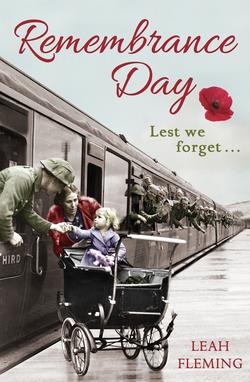

Читать книгу Remembrance Day - Leah Fleming - Страница 12

4

ОглавлениеAugust 1914

‘They can’t take all the horses away! They just can’t!’ cried Selma, watching the men in khaki leading a line of them roped together like prisoners across the square. ‘Dad! Stop them!’

Asa shrugged his shoulders and sucked on his pipe, shaking his head. ‘They’ll be well looked after if they’re doing war work. Don’t take on so. The country needs them.’

‘But there’s Sybil’s pony!’ She pointed out a sturdy grey belonging to her school friend. ‘How can the farmers manage without them? You will have no shoeing…’ Selma turned indoors, unable to watch this terrible procession, hardly believing what was happening.

In just a few weeks since the Bank Holiday war had been declared, everything was topsy-turvy in the village. The Rifle Association had taken over Colonel Cantrell’s bottom field for target practice, there were posters everywhere demanding citizens be on guard for German spies. The railway line was patrolled day and night. The Territorials were making preparations to leave from Sowerthwaite station.

Poor Mr Jerome, the old German photographer, had had his windows smashed and his equipment taken in case he was in league with the enemy. All the talk in school was about the wicked Hun stealing poor little Belgium.

Now the district had to yield up a quota of serviceable animals: hunters, cart horses and drayhorses, ponies. How could the milkman manage without Barney, or Stamper, the coalman’s steady Dales horse? They were taking all the beasts she’d known all her life down the road and across the sea to a foreign land. They would be so bewildered and scared. Selma was sobbing as Essie tried to comfort her.

‘They’re not all gone. Don’t fret. Lady Hester’s hunter is still in the barn out of the way. It was a good job she was being shoed here but I expect she’ll go with Master Guy or Angus before long.’

Selma wept over these dumb beasts that had no say in their fate. Next it would be her brothers and the boys who stood at the notice board regarding Lord Kitchener’s big poster: ‘Your Country Needs You’, his finger pointing accusingly towards her. Well, he wasn’t having any of her family. They were blacksmiths and farriers; important trades that kept the farm machines at work. Men could volunteer but her dad would have more sense and her brothers were too young. They knew nothing about fighting wars.

Suddenly it felt as if the whole world had gone mad. There were flags and bunting in the streets, and cheering processions as if this was something to shout about. Soon the village horses would pull guns and the guns would be let off and people would be getting killed. All because some duke they had never heard of got shot in a country she couldn’t find on the map. Why had they got to get involved? No one had explained it to her satisfaction, not even the Head, Mr Pierce, whom she’d heard was enlisting in the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, the famous ‘Havercake lads’.

‘Now the army’s gone, take Jemima out of the barn and into the paddock, Selma. Keep busy and don’t fret is my motto,’ Asa smiled. ‘Go and take that miserable face into the sunshine. Happen it’s time to stop the bullyboys in their tracks and show them what all our King’s men can do. Go on…wipe yer tears and get a bit of fresh air in your lungs.’

Selma led the tall chestnut mare out into the sunshine. She loved this gentle giant who had carried Guy on her back. The groom would be ages before he came to collect her, and then she remembered that Stanley and the stable boy had enlisted together to go with the horses. There was just the chance that Guy might…No, she mustn’t hope too much.

The late August afternoon sun beat on her forehead as she led the horse into shade and towards the slate trough where cool fresh water bubbled up from a natural spring. Soon the holidays would be over and she would take her post as proper teaching assistant alongside Marigold. Her brother, Jack, was with the Territorials and she kept boasting about him being the first in West Sharland to take the King’s shilling and asking why her brothers weren’t in uniform yet.

‘You have to be eighteen,’ Selma replied.

‘Who says?’ Marie sneered. ‘You don’t have to take your birth certificate. No one in Skipton would guess that Newton was underage if he signed on there.’

‘He has to help Dad.’

‘Frank can do that…Anyroad, when the horses go, he’ll have nowt to do, my dad says.’ There was no arguing with Marie. She was always right, but not this time. It was official. Dad needed an assistant and Frank was only sixteen and not very tall.

The urge to mount Jem was now just too hard to resist. They were old friends and riding bareback was no problem for Selma. ‘We’ll not let you go with those soldiers,’ she whispered in her ear. ‘You can hide in our barn any day. Now you and me can have a little trot round the paddock or I can ride you home, if no one comes for you.’ Guiding the horse to the mounting block by the gate, she slid onto her velvety back and nuzzled into her mane, kicking with her heels to set Jem on her way. But the mare had other ideas and began to gather speed. Then with a whoosh she jumped the stone wall into the next field with Selma clinging on, hair flying, her face flushed with the fun and freedom of chasing the wind. This horse was no sloth and shot off at speed, cantering across the last of the mown hayfields, frisky, disobedient to Selma’s commands. There was nothing to it but to relax and enjoy the bumpy ride, let the horse have her head for a while but what if she got injured and Dad had to get the veterinary out to repair the damage? ‘Stop! Who-ah!’ Selma dug hard and raised her voice. She pulled hard on the reins and mane to no avail. Then Jemima suddenly halted, jerked and threw Selma to the ground, leaving the horse bolting off out of reach towards the river bank.

Selma lay winded but laughing, smelling the clover, meadowsweet and honey of the scratchy stubble. Another horse was flying across in pursuit. The horseman jumped down and came to her aid.

‘Are you all right?’ It was Guy, like a knight in shining armour, lifting her up to let her hobble to the shelter of the stone wall. ‘She can be a monkey if you don’t check her.’

‘I’m fine, just my pride hurt. I thought she’d like a genteel little trot but she just decided to let rip. Sorry.’

‘Just stay put,’ Guy ordered, and he was back on horseback and cantering off in the direction of the far field where the chestnut hunter was casually grazing. He tethered her to his own horse and walked them back.

‘No bones broken this end,’ Guy laughed. ‘I gather your father hid her in the barn when the soldiers came but we have permission to keep her awhile longer. I was coming to collect her.’

‘We heard the grooms have enlisted,’ Selma said, not believing her luck in having Guy all to herself.

‘Lucky blighters! I wish I could go now. They say it’ll all be over by Christmas but I hope not. I’ll only just be seventeen then and I don’t want to miss the show.’

‘You make it sound like a firework display. Did you see they took twenty horses?’

Guy nodded. ‘Mother is furious. They took the trap ponies…One day this old lady will have to do her bit, won’t you?’ Guy nuzzled the horse. ‘I hope she’ll come with me when my turn comes.’

‘Has the colonel gone to France?’ Selma asked, hoping it wasn’t a secret.

‘He’s at HQ with Lord Kitchener, would you believe. Father says it will be a long show and no picnic getting Kaiser Bill’s army out of Belgium, though.’

‘Will you be joining up?’ Selma dared to voice the question that had been in her head for days.

‘As soon as I can, and Angus too. It should be splendid fun going to France. And your brothers? I know Father expects the village to fill its quota.’

‘I hope not…they’re needed at the forge. Mam’ll never let them sign up underage.’

‘My mother neither, but everyone has to answer the call as best they can. It’s sort of expected at school that the cadets set an example.’ His eyes glazed over with pride and determination.

‘Why do we have to fight for people we don’t know?’ Selma said, not convinced.

‘Because if the Hun comes here, he might do to our womenfolk what he’s done over there. No one is safe from bullyboys. You have to stand up to their threats and show them your fists, stand and be counted. The sooner we go, the sooner they’ll be kicked back to Germany where they belong.’

‘Everyone’s going mad about this war. I don’t want you all to go away…It’ll be a village full of old women and kiddies.’

‘I know this is a bally cheek, but if I do enlist would you write to me…about the horses and the village and all that stuff? I’d be awfully grateful, but if you think I’m being a bit fast…It’s not as if we’re…you know,well…’Guy stuttered, his cheeks flushing.

‘I’d like that but you’ll have to write first so I know where you are,’ she replied, trying to keep the excitement out of her voice.

‘Try and stop me. I expect we’ll be months doing boring training and all that. If you’d like to exercise the horses while I’m away, I’m sure Mother wouldn’t mind. You have a way with them, all you Bartleys. Jemima can be a fussy old thing.’

‘So I see,’ Selma laughed, and then wished she hadn’t. ‘Ouch! That hurt.’ They were nearing the paddock and the final gate through into village view. Selma couldn’t stop looking up at her rescuer. ‘You won’t leave before you say goodbye, will you?’

‘It’ll be ages yet. We have to go into school until the end of term or Mother will have a blue fit. Once I’m seventeen she can’t stop me doing what I want, though. Perhaps we could go for a walk one afternoon soon? We could meet under the river bridge.’

‘As if by accident…’ Selma nodded eagerly. ‘That would be the best.’ It wouldn’t do to blaze their friendship in front of her neighbours. Both of them knew that without having to spell it out.

‘What about next Sunday before school starts up?’

Selma smiled and flushed, feeling strange to be agreeing to something both of them knew was breaking some unwritten rule of decorum. But so what, Selma thought. The whole world was breaking rules, storming into a neutral country, ransacking homes. Theirs was a very minor misdemeanour compared to that.

‘Is it true what they’re saying on the market, Lady Hester?’

Hester turned from her basket of materials in the church hall with impatience. ‘What is it now, Doris?’ If some of these young mothers spent more time sewing and less time gossiping, they might be able to finish their quota of saddle pads, limb bandages and ambulance cushions for the troops on time. There was a list of knitted comforts for soldiers for Christmas still to do.

‘We heard the Hun has poisoned all the black spice in the hedgerows,’ Doris replied, and her friends all nodded their heads.

‘What utter bunkum! The blackberries were all picked ages ago before the first frosts. It’s October now, and the crop was poor because of the hot summer, my cook tells me. You mustn’t believe such rumours.’

Doris was not to be put down. ‘Well, I heard that we mustn’t use eau-de-Cologne or eat Battenberg cake. It’s unpatriotic, it said in the paper.’

‘Then use lavender water and call it marzipan slice, if you must. I don’t see how that helps the war effort, but concentrating on your stitches does,’ Hester snapped back, tired of their tittle-tattle.

These meetings were a chore but Hester was not one to shirk her duty to the community, though her fingers were raw from the rough cloth. The poor souls at the barricades needed all the help they could get and she was going to make sure West Sharland delivered whatever was asked from the District Ladies Comforts Fund. The older women were no bother, sitting primly in their best hats, thimbles at the ready. It was the young fry—farmers’ wives, tradespeople—who were eager to volunteer but not so keen to work. The village was pulling together under her tutelage and the vicar’s call to arms. She took back all she had said about his wife, Violet. Mrs Hunt was proving to be indefatigable in chivvying up the congregation. Her son, Arnold, was now serving in France and the news wasn’t too good there, judging from his letters home.

Most of the women here had family going to the front. Betty Plimmer’s boy, Jack, was the first to enlist when the recruiting sergeant held a parade in Sowerthwaite, the nearest town. Everything was all very satisfactory, according to the local Gazette, but Charles hinted it would be a long war and the casualty lists were getting longer.

She was dreading the moment her boys turned seventeen. There was pressure for Sharland pupils to be commissioned, of course. Their training was seen as an advantage, shortening the time for official training. Officers of such stalwart character were needed urgently, but not her sons, not yet.

Angus was bursting with keenness. But what if he had another seizure? She had told Charles to use his influence and get him a home posting, something not too vigorous. He’d just laughed and told her to stop mollycoddling the boy. ‘Cantrells go in the thick of it! It’s what we’re bred to do.’

‘But they’re so young. Plenty of time after school,’ she had argued.

‘Fiddlesticks, woman! What sort of chap do you think I am to hold back my sons from glory in the field when I’ve been round every farm and house in the village making sure all the able bods are rooted out and volunteered into service? I can’t let one of my own be seen as a slacker…’

In her head she knew he was right, but her heart was fearful. You didn’t bring children into the world to be shot to pieces. How could it have come to this?

‘Lady Hester, are you feeling unwell?’ Violet whispered softly. ‘You look as if you’ve seen a ghost.’

She had been daydreaming again, staring into space, making an utter fool of herself.

‘I’m just making lists in my head. So much to do…so much to do,’ she replied, fooling no one.

‘The bell will ring soon,’ Violet continued.

At noon every day St Wilfred’s church bell tolled the hour to remind the village to halt work, bow and pray for those who were fighting. The room fell silent and afterwards it was time for them to break up for luncheon. For once Hester decided to walk home unaccompanied. Time for some fresh air before afternoon visits began. Her days were so full there was hardly time to change from morning gown to afternoon dress, but duty and standards must be set, war or no. She must fly the flag of confidence, no matter how terrified she was feeling.

Essie paused at her scrubbing when she heard the wall clock strike twelve. ‘Lord have mercy on our boys, wherever they may be and give courage to their folks at home,’ she prayed. Then she carried on rubbing over the flags on her hands and knees until she saw the shadow fall over her and a pair of size ten boots in front of her nose. The polish on his toecaps made her stomach turn over. She looked up. ‘I’ve done it, Mam. Took the King’s shilling. I’m off to war!’ he announced, grinning as if it was something to rejoice about.

‘Oh, Newton Bartley…whatever for? What’ll yer dad say? He needs you in the forge.’

‘No he doesn’t. He’s got Frank to pump the bellows. When I told them my trade, they nearly bit my hand off…asked if I could ride and I leaped on one of their hosses in one jump to show I was not kidding. It’ll be the Artillery or Engineers for me. I might get to work with hosses in the cavalry…I won’t be in the front line but doing what I’m good at. Don’t cry…I’ll be back.’

Essie couldn’t hide her tears. ‘Oh, I wish you hadn’t…but I’m that proud of you, just the same. At least they won’t send you abroad until you’re nineteen.’

‘I told them I was eighteen and a half,’ Newt confessed.

‘Well, you can just go and untell them. If you don’t I will. You’re not eighteen until next March. Don’t be in such a hurry to wish your life away.’

‘It’s my life. I hate it when people eye you up and down in the street for not being in uniform. There’s loads of lads joining up together. The colonel’s been up and down the streets checking who’s joined up. I think one of us should go.’

‘But not to please him. Yer dad has already chewed off his ear when he poked his head round the smiddy door. He told him someone had to keep the wheels turning and machinery in fine fettle and the farmers’ hosses on the trot. That’s war work too. The colonel went red in the face and stormed out but yer dad got the last word on’t matter.’

‘I’m not going to please anyone—or the lassies, before you start—but ’cos I sort of have to…to prove to meself that village lads are tough and reliable and stand up for what is right. Don’t be mad at me; I’ll write to you.’

‘You’d better had, young man. When will you tell yer dad?’

Newt looked sheepish. ‘Not yet a while. I’ll wait until he’s cooling off. I don’t fancy breaking the news with him with a hammer in his hand.’ He grinned and Essie wanted to hug him, her first-born, the daft happorth! He had that stubborn mule Bartley streak in him, a devil to shift. Selma had it too, but Frank was more her own makeup, sensitive and feeling. Essie shivered, knowing this blessed war had just crept through her front door and stolen a son.

Angus and Guy stood in Otley Street outside the Drill Hall in Skipton sizing up the queue, the bustle of lads coming in and out, the giggling girls hanging around the gates waiting for their chaps to come out smiling, waving papers.

‘Come on, don’t hang about,’ Guy said. ‘Let’s get it over with, we’ve not got long.’

‘Not so fast,’ Angus grinned. ‘We can have some fun here. I’ll go in first and you wait outside…’

‘What for?’

‘You’ll see.’ Angus disappeared through the arched door while Guy looked to see if there was anyone he recognised. Mother would rant and rave when she found out what they were doing but if they waited any longer the war would be over. Angus reappeared, grinning. ‘Your turn, give your initials and wait and see.’

Guy stepped inside and joined the queue. He felt conspicuous in his striped school blazer. He stepped up to the table where the Sergeant Major looked up at him with surprise.

‘What’ve you forgotten, lad…changed yer mind? Let’s be havin’ you! Next.’ He ignored Guy and looked to the boy behind.

‘Sir, I’ve come to enlist,’ Guy offered.

‘Oh, aye? You can’t do it twice, laddie. I’ve got you on the list already. Next!’

‘That’s not me,’ Guy said.

‘I’m not deaf dumb and blind…stop wasting my time. See this joker out!’ A soldier made to manhandle him out of the door. So that was Angus’s little game.

‘Thanks a bundle! They wouldn’t take me…’

‘Don’t you think it’s better if only one of us goes? Poor Mama will have a fit,’ Angus offered.

‘Don’t be so stupid! You’re the one who ought to stay at home, not me.’ Guy dragged his brother back into the hall. This time there would be no monkey business. The Sergeant looked up as they both saluted and roared, ‘Well, I’ll be damned! A right pair of jokers, we have here! We’ll soon wipe the smile off your faces…’

Selma was busy supervising the junior knitting bee when the noon bell tolled. The children rose, put their hands together and offered a silent prayer. Soon the dinner break would start and she must make sure the knitting was well away from spills and sticky fingers. They were attempting mittens for soldiers. Some of the girls were experts already with knitting needles fixed to their belts, but her boys were all fingers and thumbs even though everyone was taking it as seriously as any eight-year-old could.

The autumn sun beamed down through the high arched school window, dust and chalk motes sparkling in the light, no sound but the clacking of needles and squirming clogs on wooden boards. Barbara Finch had just been sick again and sent home though the smell of vomit and sawdust was still in the air, as was the stink of someone’s dirty socks, but for once her thoughts rose above her own knit one, purl one to those afternoon walks with Guy…

How many Sundays had they met in secret now? How she longed for that precious moment when she stepped onto the secret path, through the iron gate up onto the scar to avoid the usual Sunday strollers and Sharland scholars, her heart beating fast, anticipating the moment when Guy would step out onto the path ahead of her as if by magic and she could drink him all in, those long striding legs, the sway of his hips, the moment when she caught him up and he looked down at her, inclining his head as if he was appraising her for the first time, smiling with those bluest of eyes, holding out his hand, his long fingers grasping her hand with such warmth and tenderness as they held each other in such a gaze that made Selma feel dizzy. It was as if the whole world stopped for those precious hours when they could lose themselves in each other, holding hands like any courting couple but always with one eye on the horizon in case they were discovered, hands separating as they drew close to the village to go their different paths. Sometimes Guy left Jemima tethered close by and they took turns to ride and walk up to the far ridge from where they could see the whole valley spread out before them.

Last week Guy sat staring out over the hills. He’d just heard that one of his school friends had been killed while on training with live ammunition. His name would be the first Sharlander to go on the Roll of Honour but not the last. Both of them sensed that this war was changing lives for ever and Selma felt a flash of fear that this was only the beginning of things to come. They sat under the shelter of a huge piece of granite rock; an erratic, Guy called it.

Selma noticed how when she talked to him her voice softened and her vowels rounded and deepened away from broad Yorkshire, taking her cue from his own refined accent. They were reading from his pocket Palgrave’s Golden Treasury.

‘You read so well and with such meaning like an actress,’ Guy said.

‘I’ve never been to a proper theatre,’ she confessed.

‘Then you must go…perhaps to Bradford or Leeds on the train.’

‘I don’t think so…we don’t go to those places.’

‘Not even to Shakespeare? You just have to see one of his plays. School’s going to do Hamlet next term but I won’t be there.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I was thinking if we got up a party now, a crowd from the village for a train trip or something, your pa’ll know you’d be safe. It’ll be fun before I…’ Guy paused. ‘It’s no good. I’ve got something to tell you…’ He was looking at her with such serious eyes and she knew what was coming.

‘Oh no, not you and all? You’ve never joined up, have you?’ Selma’s heart sank as Guy winked and smiled.

‘Officers can join at seventeen, you know. I can’t sit about and do nothing when other chaps are getting on with the job.’

‘My brother lied about his age and joined up too and now our Frank is going round with a face like a wet weekend and Dad threatening to chain him to the horse’s stall if he does the same. Why do you all want to rush off? Your mother will be as worried as mine is now.’ Selma felt sick at this news just when they were getting to know each other. What would happen to their Sunday walks?

‘Actually she doesn’t know yet. We’ll pick our moment but she can’t stop us. We can get written permission from Papa if she won’t agree. Secretly, she’ll be very proud. We’ll be in training for months so she’ll get used to us being away before we’re sent off somewhere.’

‘It won’t be the same though, will it? I mean our walks and talks…’ Selma blushed, knowing how much she’d miss them.

‘I’ll be home on leave,’ he offered.

‘It won’t be the same though, will it?’

‘Why not?’ He looked puzzled.

‘It just won’t, I know it. You’ll be doing manly things while I’m stuck in school with the baby class to teach.’

‘That’s important work too,’ he said with such a look of tenderness in his eyes. ‘I’ll be larking about marking time, playing pranks with Angus. It’ll be just like school. We have to do our bit.’

‘I’ll miss you.’ Selma felt tears of disappointment rising up as she gazed back at him.

‘I’m glad to hear it,’ he whispered, his face drawing ever closer so they were almost touching. His lips found hers in a soft kiss and they stared at each other with surprise.

‘I’m sorry…I’ve never done this sort of thing before,’ Guy apologised but, tipping her chin towards him with his finger, he kissed her again and they clung to each other, breathless.

‘Me neither,’ Selma whispered. The look between them stirred her to the pit of her stomach as they drew close again, kissing and hugging.

‘You are my best girl, Selima Bartley, do you know that? My best girl.’

She drew back,laughing.‘How many others do you have?’

‘You know what I mean. Ever since I saw you rescuing my brother…’

‘Ever since I saw you in that bathing costume,’ she giggled. ‘But I don’t want you to go away…’

‘I’m here now so let’s make hay while the sun shines,’ he said, pulling her down onto the grass.

Selma surrendered herself to this delicious moment. There was so much to learn.

‘Miss…Miss, I dropped a stitch again.’ Selma was jolted back to work. No peace for the wicked, she smiled. This secret courtship warmed her heart and fired her resolve. She would not let Guy down with shoddy knitting. ‘Come on now, children, winter is upon us and those poor soldiers need warm fingers, not mittens with holes!’

Hester sat bolt upright on the horsehair sofa, one eye on the grandfather clock in the corner of the farmhouse parlour. It had a brass face of some distinction, as did the dark oak furniture with fine pewter plates in racks. In her hand a piece of porcelain of antiquity that unfortunately smelled and tasted of musty damp from the china cabinet. The rounds of the sick and elderly were done and she always finished off at the Pateleys’ farm at the top end of the village out on the old high road to Sowerthwaite. It was set back among the trees with a fine view across the valley. Whoever had chosen this site knew his arse from his elbow, as Charles would say.

She smiled, knowing her dutiful day was done and Beaven would be waiting to return her to Waterloo House for tea and hot pikelets dripping with this season’s raspberry jam. The fire would be roaring in the morning room; they were setting an example of austerity by having only one fire lit during the week to save fuel.

‘How’s them young ’uns?’ said Emma Pateley, the farmer’s maiden sister, who kept home for him now he was widowed.

‘Ah, growing up too fast,’ Hester offered. ‘Still at school, of course…too young yet for any war work.’

‘Is that so? But not too young to go a-courtin’,’ Emma chuckled. ‘I seed one of yourn the other day up the far field walking a horse with a girl on its back. A proper knight in shining armour he looked.’

‘I’m sure you’re mistaken,’ Hester protested. ‘The boys are busy at school.’

‘It were a Sunday afternoon, as I recall; he were on that chestnut mare, fine beast. You were lucky the army didn’t get her on a rope. Tall as a spear, fair lad. The girl were dark-haired like that one of Bartleys’ as teaches school. You know, the one with the funny name. I’d watch it there. Them chapelgoers can be trouble when crossed. They like to match with their own.’

‘I’m sure it won’t be one of my boys, Miss Pateley.’ Hester felt herself flushing. Emma could be a gossipy old crone but her eyes didn’t miss much. The boys, it was true did have free periods on Sunday afternoons but surely one of her children wouldn’t make a fool of himself in the village?

‘When men and maids meet, there’s allus mischief, my lady,’ Emma continued, unaware of Hester’s discomfort. ‘Lads will be lads, and lasses aye let them…’

‘Thank you for the tea, Miss Pateley, but I must take my leave of you. Things to do in these trying times.’

‘I ’eard as how old Jones the plumber’s boy copped it last week and him a regular in the army. He’s been out there since it began…He’ll not be the last. My cups are telling me we’ll all be wearing black afore the next year’s out.’

‘Yes, yes, perhaps…Now you’ve got some more wool for the socks. I hear you’re one of the best heel turners in the district. We want to send socks, scarves and comforts by the end of next month, parcels for our local boys. I can rely on you?’ Hester wagged her finger, desperate for Emma to stop talking.

‘I’ll do my best. Thank you for calling on a poor old soul as is cut off from the world up here.’

Not so cut off that you can’t find gossip, mused Hester as she stepped briskly into the waiting carriage. There was something about the woman’s ramblings that unsettled her. Could one of her boys really be making a fool of himself with a village girl? How ridiculous, how stupid, to foul on your own doorstep! How dare he shame the family? No doubt it would be one of Angus’s pranks. He was always up for silliness. Had he no respect for his station in life? Just wait until their next exeat: she’d lay down the law. A liaison with a villager was simply unthinkable.

Guy saw the thunderous look on his mother’s face after church and wondered what was up. She’d been acting strange all morning, silent and severe. Had another under gardener left them in the lurch? She plonked down her Prayer Book and her gloves, and pointed the twins into the cold drawing room.

‘Inside…both of you,’ she ordered, out of earshot from Shorrocks, who was hovering by the hall stairs with their coats and hats.

‘Now which one of you has been silly enough to pay attention to the Bartley girl?’

Neither of them spoke but stood together to attention while she choked them off.

‘Don’t look at me, Mother,’ said Angus. ‘I’ve not been near the village for ages.’ He turned to Guy. ‘And Guy’s head has been stuck in a poetry book, hasn’t it?’

Bless Angus for covering for him, but Guy was not ashamed of his friendship with Selma.

‘Don’t blame Angus. Selma and I have been walking out, riding Jemima. She’s awfully clever, you know, training to be a teacher. You’ll like her when you meet her.’

‘I have no intention of doing any such thing. At your age, walking out with a blacksmith’s daughter and a nonconformist—have you no sense? You should be in school, not gadding about with a girl, giving her false expectations. You are far too young for such matters and there’s a war on. Why didn’t you tell me this was going on, Angus?’ Hester accused.

Angus shrugged his shoulders. ‘It’s all news to me,’ he grinned.

‘Have you nothing to say, Guy? Stop grinning at each other like simpletons.’

‘Sorry, Mother, but we’re not kids any more. We’re old enough to volunteer and take up commissions—’

‘That’s as may be, in good time,’ Hester interrupted.

‘No time like the present.’ Angus threw in his verbal grenade,standing to attention to salute. ‘We’re soldiers now, all signed on the dotted line.’

‘You have done what!’ she exploded. ‘Behind my back? I forbid it!’

‘You can’t, Mother. It’s done. We’ll be off to training camps in the next week or so.’

Guy felt sorry for his mother as he saw her bravado crumple. She sat down, pale-faced, deflated for once, speechless at this news. ‘Does your father know about this madness?’

‘We’ll write to him. It’s only what he expects of us.’

‘But, Angus, you can’t go, not with your recent affliction. You won’t pass a medical, not with your history.’

‘Don’t fuss. I’m fine now. It’s going to be such a wheeze. Oh, don’t cry, Mother. We’ll be fine and they might let us join the same regiment.’

‘I see you have got it all worked out behind my back. Does this Miss Bartley know your plans too? I dare say she’s behind all this show of gallantry,’ Hester said, her lips composed, her arms crossed tightly against her bodice.

‘That’s not fair. Her brother’s going too. Everyone’s going. You both worked hard enough to make sure half the village boys answered the call to arms.’

‘But not my sons, not yet, not my two boys at once. Why can’t you wait? There’s no hurry,’ she pleaded.

‘The sooner we leave, the sooner our training begins and the sooner we’ll be in action before it all fizzles out. I’d hate to miss it,’ Angus added, his eyes bright with fervour. ‘Guy will keep an eye on me, won’t you?’

‘I can’t take this in, all this secrecy and I’m the last to know. Why?’

‘Because we knew you’d take on so…You must let us be like all the others and give us your blessing.’ Guy sat down beside her, trying to jolt her out of her maudlin mood. It was not like his mother at all.

‘I have a bad feeling about this. It’s too soon. What will I do without you?’

‘What you’ve always done: put a brave face to the world and get on with your charity work and church duties, keep the home fires burning, as the song says, and make sure we get clean socks, hankies, some of Cook’s marmalade, pipe tobacco and up-to-date newspapers. Don’t be sad, be glad that we’re old enough to be useful to our country in its hour of need.’

‘Oh, Guy, do you realise what you’re doing?’ She was shaking her head, not looking at them both.

‘I’m not rightly sure but all I know is that it must be done now…Come on, chop chop, no more moping about. There’s the luncheon gong. I hope it’s roast lamb. Dry your eyes. We’ll get plenty of leave while we’re training. Might even get as close as Catterick camp. Buck up, old girl. It’s not the end of the world.’

But it is the end of my world, sobbed Hester as she paced the bedroom floor later that night, the gentle tick of the marble clock lagging far behind her own heartbeat. How can I live if anything happens to my sons? No sooner out of the nursery than into school and now into the army, and Guy on the arm of some trollop. She’s behind it somewhere. Prim school miss she might appear but there’s fire in those dark eyes and she’s not getting her claws into my boy.

Hester sat on the window seat, drawing back the brocade curtains to reveal a night sky lit with a thousand stars.

There’s one good thing about all this, though, she thought, drying her eyes. Once Guy disappears from the scene, all this mooning about will soon fizzle out. I’ll put him in the way of some decent county girls from good families; girls of our own class, not upstarts no better than servants. At least he’ll be too busy to satisfy that girl’s craving for influence. And as for Angus…Hester smiled a knowing smile. There must be ways to make sure he got no further than the medical board. Perhaps she could let Guy go now, but not two, oh dear me, no…Angus must stay close by, whatever it took.

First the horses, then the men, and the village fell silent as it went about the daily grind. I sigh, looking around the crowds. Everyone thought it was ‘all a bit of a bluff and wouldn’t come to owt, as old Dickie Beddows had pronounced. I’ve not thought of him for years, sitting under the elm on the bench with string tied round the knees of his corduroy breeches, sucking an empty pipe, dispensing his wisdom to those who had the time to listen. But as the months wore on and curtains were closed in respect for some mother’s son who was lost in places they couldn’t pronounce, even he fell silent.

Then there was the shelling of Hartlepool and the Zeppelin raids that bombed Scarborough and the east coast. Yorkshire was under attack; a terror none of us could understand; little kiddies crushed under bricks, mothers cooking breakfast blasted to eternity. This was no bluff.

How strange that I can recall every detail of that time yet forget what day of the week it is so easily, or what I’ve had for supper.

Being here brings everything to the fore. Nothing’s been lost in the house of my memory. I can walk round its rooms and recall those far-off tumultuous days at will.

The elm tree may have been replaced by a sycamore, the guard railings removed with most of the cobbles, the chapel is now a spacious house, but I can see it all as it once was.

The school is still functioning, with its fine playing field. It was my refuge from all the worries of war and home. Things were never the same when Newt left. Frank took his desertion to heart and wouldn’t settle. Oh, Frankland…

All the King’s horses and all the King’s men, couldn’t put you together again.