Читать книгу Remembrance Day - Leah Fleming - Страница 15

6

Оглавление1916

Hester felt proud of her effort. A thick bowl of broth, with mutton bones, pearl barley, vegetables chopped and lots of salt and pepper. They were having a penny dinner in the church hall to raise funds for the new Women’s Institute. To her surprise she quite enjoyed getting stuck in, wearing a long white apron and a lace-edged cap, while Violet Hunt chatted away about all the things this new society might do to help the war effort.

‘We need a committee and you must take the chair, of course, Lady Hester. There are groups springing up all over the district. It’s all very exciting.’

Violet was becoming a staunch ally and, for a vicar’s wife, most liberal in her views. It was she who suggested it might be politic to invite the chapel women. This was an interdenominational institution, after all, open to all women, married or single, and a splendid way of galvanising all their working parties into one big effort. Instead of lots of separate meetings in order to publicise all the new directives from the government about saving fuel and food and equipment, they were going to pass on useful tips and skills. It would give the wives of soldiers something to occupy their evenings after an outbreak of khaki fever in the district and some unfortunate incidents between visiting soldiers and local women.

Hester stirred the soup pan, sniffing the delicious aroma. Who would’ve thought a year ago she would have to cook some of her own meals, tidy her own room, see to some of her mending and, her most daring venture to dare learn to ride a bicycle.

Cycling up and down to the shops with her basket was most invigorating in the fresh air, and once or twice on a bright day she’d ventured further afield, shortening her riding skirts to prevent them catching on the chain. Sometimes down the green lanes with stonewalls enclosing her, she heard the curlew bubbling over the fields as she watched the lambs gambolling, almost forgetting that there was a war on. It was all so peaceful and serene. It was impossible to contemplate that five hundred miles away young men were being killed.

She was getting used to the boys being away now, believing Charles when he’d said that they’d not be shoved across the Channel without proper training. Their letters were brief chatty notes full of a world she hardly knew these days. Hers in return were full of how war was changing her domestic life, how the village community responded to the sad news of boys who would never return home. She told them about Violet’s new idea to form the Women’s Institute like the ones set up in Canada, which her sister had joined.

But the casualty lists were never far away from everyone’s mind. Charles hinted that there was a big push coming when the weather faired up; a push in which her sons would surely be involved. The French were taking a pounding, holding their forts at Verdun against terrible odds and suffering atrocious bombardments, so the paper said.

Keep busy and don’t think too much was her maxim now. Fill every day with things to do, shore up the gaps with busyness. The garden was turned over now into one big allotment, and potatoes chitted and planted before the ninth of April, the traditional date for planting here. She’d been on her hands and knees with the best of them now she was down to just one old gardener. Everything was dug over except her rose bed.

There had to be some vision of colour and hope to look forward to, she sighed, noticing, as she returned to her morning room, the postman cycling up the drive. As she saw him pull out a telegram from his bag, she went cold.

Hester made for the drive to meet him. It took every ounce of courage to look nonchalant. Old Coleford, seeing her anxiety, waved the paper jauntily in the air.

‘Nowt to worry about, your ladyship. ’Tis only from yer son…’

She could feel the weakness of relief seeping into her limbs. It was all she could do not to snatch the paper from his fingers but she stood nodding politely.

‘Thank you, Coleford,’ she managed to say, before taking it to the bench against the south wall, and tearing it open with shaking fingers: ‘Meet me at the station. The four o’clock train. A.’

What a relief. Angus was home on leave!

The news sent her into a flurry of flower arranging, lists for Beaven the coachman to do, engagements to cancel, sending the relief maid upstairs to air his bed. There was a menu to shop for. Angus was coming home. It was going to be just splendid!

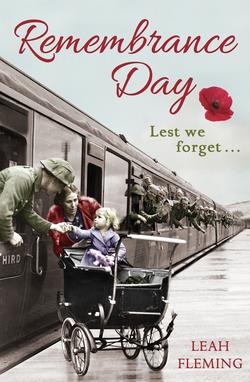

The train was late and she was miles too early. Beaven had brought her down in the pony and trap, knowing she was impatient to be on the platform as the steam train chugged slowly into the station. The porter was hovering and the stationmaster fussing with his watch and chain.

Then doors clanged open to disgorge scruffy soldiers, unshaven, weary-faced, in muddy uniforms with kitbags on their shoulders. Boys who had travelled for days to snatch a few hours with their families on leave. Some fell into the waiting arms of their womenfolk. They all looked exhausted.

Then from the first-class compartment she saw Angus step out slowly but not in his uniform, looking ordinary somehow in a long tweed coat, carrying a suitcase. How strange. He was shuffling along like an old man and, to her horror, leaning on a walking stick.

‘Angus, darling! What a surprise!’ Hester smiled, reaching out to greet him.

‘Not now, Mother. Let’s get out of here.’ He didn’t look her in the face but shuffled over the railway bridge and out through the station gate into the trap, pulling his trilby over his face. He didn’t speak all the way home, but sat sullen, staring out into the dusky night.

Hester could hardly breathe with the shock. What on earth was going on?

Once through the hall, Angus plonked his case down and went straight to his room. She followed him up slowly, fearing the worst. Had he been cashiered out of the army for a scandal, failed his examination, found wanting in leadership? What had Angus been up to and why had Charles not warned her of this disgrace?

Opening the door, she found her son sitting on the bed, sobbing, shaking with distress like a little boy.

‘Angus! Pull yourself together and give me some explanation,’ she ordered, knowing she must be hard to bring him out of this childish display of emotion.

‘I had another bloody fit, didn’t I, right in front of everyone on parade when we were standing to attention. It’s when I get that smell…like iron filings, a metal iron smell, and the flashing lights—my fireworks, I call them—and the next thing I wake up in the hospital ward and they were prodding and poking and asking questions. I made a right tit of myself again. Why? It’s not fair just when we were shipping off to France. It’s just not fair. I’m going to miss it all, discharged on medical grounds as unfit for service,’ he grimaced. ‘All I ever wanted to do is taken from me and now I’m useless and there’s nothing wrong with me. Not even a bloody war wound to show…How can I ever show my face again? They’ll think I’m a conchie or a coward.’ He flung himself down on the counterpane. ‘Just leave me alone…’

Hester didn’t know what to say to comfort him when all she was feeling was relief that one of her boys was not to be going to the slaughter fields. One day he would thank them for saving his life but now he was in the throes of frustration.

She summoned Dr Mackenzie. They needed a proper explanation of all this.

‘In the wars again, young man?’ he said, offering his hand in sympathy, but Hester was in no mood for small talk.

‘What is epilepsy? There has to be a cure for this complaint, surely? We must find one of the best doctors—’ Hester started but Angus interrupted.

‘You’ve got to let them find me a job for the war effort. Anywhere…I can’t not be part of the show!’

The doctor sat down, trying to make sense of the distress in the room.

‘Calm down, young man. I don’t suppose you told them anything before, did you, at the first medical, about those school fits?’

‘What do you take me for? Of course not. I’ve been a year in training and no bother. Then this, out of the blue! The headaches come and go and I have been struggling to concentrate. Sometimes I go a bit blank for a few seconds but I can cover it up. I was doing perfectly fine but now I’m a freak! They say I’m an epileptic. What sort of condition is that?’

Mackenzie hesitated. ‘It’s a serious condition. There are those who suggest you might be better off in a special hospital…It can get worse…or there’s always the hope that it settles down and you never have another one.’

‘No one’s putting me into some loony bin. If I can’t do my job at the moment I’ll rest up here until I can be cured,’ Angus pleaded, pacing the floor in agitation.

Mackenzie shook his head and glanced at Hester. ‘You have to understand, laddie, there’s no permanent cure for your condition, but some pills might calm it down.’

‘Give them to me,’ Angus said. ‘Then I can carry on.’

‘I’m sorry, but the medical officers are right. You are a risk to your men, with this condition. You might collapse under battle strain. Better to stop now before you do damage.’

Hester watched him dismiss her son’s career with a wave of his hand. Angus was distraught at his honest assessment.

‘How can I live after this? I’ll have to go away. I don’t want the world knowing I’m a nutcase.’

‘We’ll do no such thing,’said Hester. ‘You have the certificates to prove your discharge. We’ll find you something to do here. What’s needed now is peace and quiet to settle whatever this is and we’ll get a second opinion from Harley Street. Isn’t that right, Doctor?’ She turned to Mackenzie with a sigh.

He nodded in agreement. ‘There are other things you can do for the war effort,’ he offered, more in hope than certainty.

‘Like what?’

‘We’ll think of something. Hiding away here is pointless. You can rest and be useful in the community. Young men are in short supply. It’s not what you wanted, but the alternative is unthinkable.’ The doctor leaned across to offer a supportive pat on the arm.

Angus made for the door. ‘I’d rather stay indoors and out of sight. I’m tired. I don’t want any supper. I’m not hungry.’

It was like dealing with a truculent child, but his distress was real enough.‘Have you told your brother?’Hester asked, sensing Angus would hate to be seen as the lesser of the two, unable to be alongside him when he went abroad.

‘No, nor Father yet. I can’t bear to think of Guy going and not me. I don’t want them to see me like this in civvies again. What am I going to do? It feels I’ve been given a life sentence. I’m not like other men, am I?’

‘Enough! You’ll change your clothes, wash your face and we’ll dine as usual. Life goes on without us and this isn’t the end of the world for you.’

Mackenzie stood up to leave. ‘Think on, young man, you’re alive when others have gone west. We’ll find you something useful to do. No one will berate you for being ill.’

‘But I’m not sick! You’re not listening. There’s nothing wrong with me but these stupid fainting fits. Oh, why me?’

Hester paused to answer his pain as best she could. She wanted to enfold him in her arms but he would only push her away. ‘Your child is your child all your life, Doctor,’ she sighed. ‘When they hurt, you hurt too.’

He nodded in sympathy. ‘Never a truer word, Lady Hester.’ He turned to Angus. ‘You must play this ball where it’s landed. This epilepsy is your battlefield now and you mustn’t let it take over your life. We must deal with it as best we can, but now is not the time to argue. You’re home and it’s time to rest and regroup and think out a strategy like your Father does. There must be a way forward, given time. Nil desperandum—don’t despair. There are other ways to serve than rattling a sabre.’

Angus ignored his departure. Hester saw the doctor to the door, leaving her son to compose himself. Suddenly her ordered world was turned upside down by his return. Her selfish prayer had been answered, but this wish fulfilled gave no satisfaction at all.

Essie didn’t like the sound of Newton’s war. His letters came in muddy-fingered clumps—when they came at all. His soldiering was hard, from her reading of his comments. He was busy fettling up gunmetal and horse tackle and delivering wire to the front-line troops. It had been a harsh winter and now his section was supporting the French troops at a place close to Verdun, if the papers were to be believed. He sounded cheerful enough but little phrases kept spearing her mind.

‘It’s a bit hellish here, and you have to watch your head from sausage bombs and shrapnel. The other chaps are grand,’ he said. He’d palled up with a lad from Bingley called Archie Spensley. The villages in France were all in ruins and his food rations sounded boring, tins of Maconochie stew and hard biscuits. The French soldiers had hot meals and were treated much better, he complained: ‘You wouldn’t feed the dog on what we get.’ But she wasn’t worried.

It was Frank who was causing her anxiety; he had got in bother for upsetting some officer with cheek. This captain wasn’t treating his horse right and Frank had showed his disapproval, which got him on a charge. Frank had always been for his horses. He wouldn’t stand any cruelty but he was young and brash, none too keen to hold his tongue.

She had joined this new Women’s Institute as a distraction as well as to do her bit. They sang the National Anthem, they had talks on cookery and other women’s matters, and sometimes held little competitions for baking and flower arranging, which was fun. It made a change from chapel and the usual chores. But she was worried about Asa struggling to cope on his own. She did what she could in the forge but the heat inside made her wheeze and cough so she couldn’t stay in long.

Selma was looking after the veg plot and exercising the horses, still writing to the young Cantrell boy, whose brother was back home now on health grounds. Betty Plimmer said he looked perfectly fit to her when he rode out on his mother’s horse. Lady Hester was busy trying to get him fitted up at Sharland School as an instructor for the officer cadets or something. It was all very mysterious. Ethel at the post office hinted he might have got a girl into trouble somewhere. Trust the village gossips to make two and two into five.

Essie tried to keep herself away from tittle-tattle. If they talked about others, they’d talk about you behind your back, she’d worked that out long ago. Better to keep private stuff in the family, and if it made her seem standoffish then so be it.

She was walking up the street when she saw Coleford approaching Prospect Row. Her heart began to thud as he moved closer to their houses. Who was it this time? Jack Plimmer from the Hart’s Head?

She scurried home, trying not to look where Coleford was going as she overtook him. He parked his bicycle by the stone wall and bent over to tie his shoe lace and smiled. Phew! Another false alarm. Praise the Lord!

She made for the snicket at the side of the cottage to let herself in the back door, leaving the gate open, and then she turned to see the old man hovering behind her holding an official brown envelope in his hand. The look on his face said it all. She cranked up a grimace of a smile as if he might perhaps move on to another door. Perhaps he didn’t have the right address. But she knew, deep in her gut she knew the envelope was for them.

‘Mrs Bartley,’ he whispered.

‘Aye, it’s our turn then,’ was all she could manage as she turned her back on him and made for the safety of her kitchen. Her hands were shaking and wouldn’t open the door properly. The envelope lay burning a hole in the table for hours until Asa came in. She nodded in its direction, unable to speak. He wiped his hands and tore the envelope, read the page, looked up at her shaking his head as if all the sorrows of the world were contained in those sad eyes.

‘He’s gone missing. Our Newton’s missing, presumed killed.’ He sat down, his head in his hands. ‘I don’t understand. We had a letter only the other day. My son…’

Asa walked back to his workshop, his shoulders bowed. Essie walked down the path to the open gate and out onto the lane and stared up at the green hills. How could her son be lost and her not know it? How could her lovely lad be so far away from her and she not sense he’d gone from her? While she was sitting, chattering away, he was lying somewhere, unseeing. They got things wrong sometimes, she thought. She would not close the front room curtains yet a while…not until the others knew. How on earth was she going to tell Selma?

Selma couldn’t believe she’d never see her brother again. He was only missing in action, Mam said. There was hope, however small. So at first she refused to go into black clothes. Frank was not even allowed home from France on compassionate leave. Perhaps he knew more than he was letting on, but he was in the north somewhere far away from Newt’s regiment. She managed to go to school in a dream, trying not to show her true feelings. Children didn’t want to see suffering faces. Her brother, said the pastor, was in a better place now. Dad nodded but said nothing as neighbours called with their little gifts of kindness: buns, pastries and vegetables. As if any of them wanted to eat at such a time. Everything stuck like pebbles in her throat. Mam just stared at Newton’s portrait and insisted the gate be kept open at the back just in case.‘You never know…he might be trying to find his way home,’ she kept whispering.

But it was Archie Spensley’s letter a week later that shattered all their illusions.

Dear family,

I am sad to have to write to you that your son and my dear friend, Newton, is no more. We chummed up straight away in Halifax and he was highly regarded as a conscientious worker and a good Christian. I shall miss his cheery company. We are greatly troubled by enemy fire in this district, which damaged our guns with shells and fragments. Your son was going forward to do a repair. There was another bombardment and I never saw him again. Be assured he would not have suffered and would want you to know you were ever in his thoughts.

May God bless all of you in your darkest hour, may He show you every mercy.

Yours sincerely,

Private Archibald Spensley

Suddenly, Selma’s parents looked old, weary and bent with sorrow. If only there was something she could do to lighten their load. Without the boys’ help Dad was sinking under a pile of unfinished orders. If only Frank could be made to come home like Angus Cantrell, who was hanging about the Hart’s Head like a knotless thread. She knew Guy was anxious to hear if she’d seen him but she was no tale-teller and said nothing to worry him.

Angus looked able-bodied enough to give a helping hand if he had a mind to it but such an impertinent request was out of the question. Lady Hester would never condone such lowly employment.

They held a simple memorial service and sang Newton’s favourite hymn, ‘Who would true valour see, Let him come hither’. She tried to sing but the words collapsed in her throat. She didn’t hear the pastor’s oration. She was living in a sort of dream. It wasn’t real because they had no body to bury, just a flag draped around the portrait he’d had taken in his uniform when he first volunteered. There were only old men and Angus Cantrell and his mother. He looked so like his brother and her heart ached at the sight of his tall frame and broad shoulders. Those who had already lost sons shielded her parents with loving concern. They had been admitted to a club whose entrance fee was young blood; a club no one wanted to join.