Читать книгу Embodied - Lee Ann M. Pomrenke - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

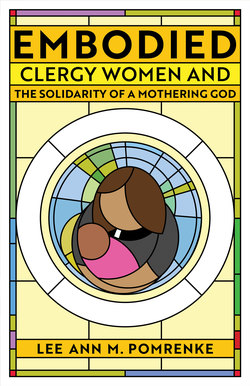

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Solidarity

“You did that good deed of adopting a child, and now God is rewarding you with one of your own!”

I blinked at the church lady. There were so many things to address, I did not know where to start. I went for human agency, with a gritted-teeth smile. “This pregnancy was not a surprise. We chose to adopt first, then to try making her a sibling.”

I also could have dived into theology: Is God really that involved with whether we conceive? We say that children are a blessing, but does that mean that people who cannot conceive are not blessed, or have not pleased God in some way? What about the fifty percent of pregnancies that are unintended—some conceived in violence, some of which cause great hardship for the mothers—how is God feeling about them? For heaven’s sake, do you think I waited for or value our first child any less than the one I will birth? By the way, you do not say things like this to other families at our church or in the neighborhood, do you? I had so many topics to handle, but in the handshaking line at the end of a church service, practicality won.

In the moment I assumed that the fact-checking answer had a slightly higher chance of changing the story the church member was telling, than the faith-related questions. Yet there are bound to be opportunities to dig into all these thoughts in my life as a clergy mother. Incidents like the brief conversation above are opportunities not just to explain my personal actions, but to challenge all of our assumptions in healthy ways. Being a pastor and a mom makes me and my family obvious case studies for many topics related to God and families (since we are already front and center and being discussed anyway). Sometimes the issues are practical, but frequently they beg for solid theological wrestling.

Certainly people talked about male clergy’s families before women were commonly seen in pastoral leadership. Yet somehow the PKs of male pastors did not reflect to the same degree on their father as they do on a mother, and the church’s historical use of mostly father images for God and male clergy for centuries enabled us to skirt the edges of these conversations. Now that clergy mothers are here in numbers, one of our many gifts to the church is instigating conversations by simply existing, such as:

• What is church for, in the lives of families with children, teens, and young adults? Why do we want them to experience belonging in church, and how do we pursue that?

• Do we expect or allow our clergy to give their personal relationships as much attention as they need? Is the model of professional ministry we have been operating with healthy for everyone?

• How does God really relate to us? Is it only as we associate culturally with fatherhood, or also the intimate, mutual impact of mothering?

We are all having bits of these conversations on the fly, but with close reading of the Bible and clergy mothers’ experiences mixed in, this book is designed to spark deeper understanding within our congregations, including more frequent recognition of God’s mothering activities among us and the experiences of solidarity that recognition can offer. What is the point of solidarity? It is significant to feel “seen,” to know that others understand your experience, so they can fully empathize. Yet solidarity is even more than a feeling of togetherness. It is community that empowers us not only to keep going and survive, but with each other’s determination and collected wisdom, to build power together. To stand in solidarity at a protest is to show with our bodies that we are neither small nor insignificant. To show up physically, acknowledging how people behave around our bodies, is a testimony to how people treat the image of God reflected in us. To show up with our voices and our stories is a testimony to God’s ongoing, loving actions standing with those of us in need of mothering, and those doing the mothering.

This is not a book for clergy mothers alone. We do not need to rehearse these stories among ourselves or discover God’s mothering actions in isolation. We need our congregations to learn from and with us, to explore these similarities between our ministries and God’s mothering behaviors and to develop a shared commitment to act upon them together. Otherwise, nothing will change. A clergy mother reading this book may feel a kinship with others who name her experiences, but she will still be carrying her experiences alone. By reading and discussing this book together with congregation members, clergy mothers and congregation members can decide together how to work on our family system and to sustain the leadership of clergy mothers. This is a true support system.

Together, we become a force advocating for a better life. Commiseration will only get us so far. God’s commiserating with us through becoming human in Jesus is meaningful, but it does not stop there. God not only feels what we feel through Jesus, but by sharing God’s own similar experiences alongside ours, gives us new ways to live into resurrection and redemption even here, even now. That is why this is not a biography, although clergy mother stories abound. Embodied is about finding the echoes of our own stories in God’s story, the solidarity that leads to new life out of death. Preachers, this is what we do. Congregation members, this is what we hope you do with us.

My experience is limited, as a white mother in predominantly white mainline Protestant churches. Some experiences of mothering are common to many, as are many of the expectations and tasks of being a pastor. Although I can read, talk with, and learn from others, I do not embody, so cannot fully comprehend, the experience of being a mother of color in the United States today. Neither can I know fully the experience of women who lead in Evangelical or Pentecostal congregations, with cultural dynamics I have never navigated. I only show up in my own body, but in the actions we have in common, we can testify to God’s solidarity together.

I am keenly aware that I would not be a clergy mother, nor would I see God reflected in those identities, without the legacy of the women who blazed this path before me. My ordination was neither exceptional nor controversial because of the ordinations of women in my denomination fifty years ago and in all the years since. I recognize a mothering God theology in the lives of clergy women because of feminist and womanist theologians, who began pushing the limits of academic theology before I was born. I start with the assumption that women have voices that matter and contribute to everyone’s understanding of the relationship between God and humanity because feminist theologians like Rosemary Ruether and Delores Williams stretched the limits of interpretation to include our perspectives. These same theologians might criticize my associating the intimate, nurturing behaviors of God with a gendered role, because tending relationships should be the domain of every Christian. I believe we can get there by giving credit to women for intimate caregiving and naming it mothering, while promising that these actions could be exercised by anybody. May later generations recognize the mothering actions of God reflected in us and assume that is a theology upon which they can build.

A Note on Word Choice and Metaphor

Throughout this book I will use “mother” as shorthand for an intimately involved, emotionally invested caregiver, and “mothering” for the nurturing actions we count on the central figure in our family to provide. That is not to say that fathers or gender non-binary parents do not behave in these ways, especially those who are the primary caregivers for their children. Indeed, they may be “mothering” in many ways every day. In a 2016 survey, the Pew Research Center reported that today’s fathers in the U.S. spend three times as much time caregiving for their kids than they reported in 1965. It is still significantly less than mothers but headed in the right direction. However, as many times as the metaphor of Father God is repeated throughout the world, we can stand to honor and pay theological attention to what has, and overwhelmingly still is, women’s work.

God does not have a gender, yet for centuries Christians chose the pronouns he/him/his to describe God. During the same many years, “mankind” was used as the inclusive term for all of humankind, or “men” was supposed to mean “all people.” Meanwhile there was very little theological reflection on mothering. God still does not have a gender, but while discussing actions that have a gendered association such as mothering, we might reclaim a little bit of time and theological reflection with the pronouns she/her/hers for God as they seem to fit. Although co-parenting fathers, single fathers, and stay-at-home fathers perform mothering actions, we do not have to name those specific actions after them for them to be included. When it is not overly awkward to do so, I have replaced pronouns with the name of God to remind us of God’s nongendered being. The language we use for God always influences our understanding and the authority we associate with certain voices in the church. I hope the words for God and God’s behaviors described in the following pages lift up women’s leadership, not only as equally important to that of men, but as unique and worthy of attention and value.

We also must acknowledge that not all mothers do these actions described as mothering, caring for their children fiercely and consistently. Mothers fail their children for all kinds of reasons, including systemic oppression, personal trauma, and addiction. A mothering God may not sound any safer or more loving than Father God does to those who experienced abusive or neglectful parents. Again, we are looking more at the actions we strive for as mothers.

Any human metaphor for God breaks down at some point, as God is so much more than human, and is far beyond our human understanding. I am interpreting God’s behaviors and perhaps underlying emotional experiences in light of my own, as a testimony from motherhood and the life of a clergy woman. When I bear witness to how I recognize God’s action in the world echoed in clergy mothers’ experiences, I testify to how even I am made in God’s image. I hope to inspire others to see God’s solidarity in their own experiences.

In comparing the role of mother to the role of pastor, I draw some parallels between children in a household and members in a congregation. Of course this is not analogous, as many church members are adults with various skills and traits that steer the congregation and provide care for each other. The analogy does not need to be taken as condescending. We are all children compared to God. To be led, cared for, and taught like children can describe the caregiver’s actions of great love, not superiority. That is my intention. Children change their parents as much as we influence them, and so it is in between clergy and the members in the pews. Bristling at this comparison I think says more about how we value children in our families than anything else. To God, we are all cherished children.