Читать книгу Embodied - Lee Ann M. Pomrenke - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

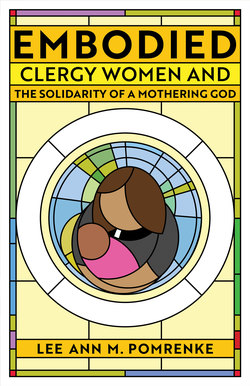

Mama in the Center

In many families there is a parent who is treated like the president, and one who is the vice president. If the president is unavailable, the vice president will do. If the president is there, however, she (and it is most often “she”) is the one the children go to for help, solace, or affirmation. The caregiver who bears that honor and responsibility may shift and change as our responsibilities outside the home change, but we all know who the president is in our family right now. This language and comparison came from a parent educator in the public school system, but the same could easily be said of our congregational life. Everybody knows who is at the center, and the Central One sets the tone for all the other relationships. Here’s a clue: It is often the primary caregiver, the one doing the mothering.

Trust

None of us are born attached to our parents or caregivers. We are born needy, certainly. When a child’s needs are met consistently by a primary caregiver, the child seems to establish a trust and bond with that caregiver (so often the mother). This bond is not innate; it comes through consistent care and affection, which is a great deal of work, especially in the middle of the night. It takes deep commitment to love and care for a child no matter what. Every. Single. Time. Parents must respond while carrying our own wounds, losses, upheaval, and even postpartum depression.

Postpartum depression can affect birth parents or adoptive parents, as it is intertwined not only with hormones and brain chemistry, but also with our own shifting identity. The reality of holding our children’s lives in our hands is terrifying and more demanding than we could have imagined. Depression tells us we are not up to the task. Scripture portrays God having some of these responses too, regretting making humankind in the first place in Genesis 6:6–7: “And the Lord was sorry that he had made humankind on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart. So the Lord said, ‘I will blot out from the earth the human beings I have created—people together with animals and creeping things and birds of the air, for I am sorry that I have made them.’” God’s emotional responses to humanity can seem unpredictable too; sometimes anger surfaces quickly, or sadness. Postpartum depression is complicated and multilayered, but these details might connect God’s experience to human responses of new parents. The Holy Spirit can speak through the honesty of others who have been through it, and even through the screening questions at our doctor’s appointments. Thanks be to God that we are not alone.

While parents adjust to our new roles in an adoption, our children are navigating how to respond, too. Adoption psychologist Nancy Verrier describes a “primal wound” in the lives of adopted children whose first central relationship (with their birth mother) was broken. That severed attachment can become a defining characteristic, showing up later as a sense of loss, anxiety, or uncertain identity. Perhaps not all adoptees experience it: we all respond differently to our circumstances. Yet that this theory exists at all testifies that the relationship with our mother is central for most of us, to who we become and how we relate to others. Congregations might consider how their attachment to a founding pastor or one who shaped their most significant years echoes in this theory.

When my husband and I adopted our elder daughter, attachment was the primary initial focus of our lives. Prospective adoptive parents are counseled on how to establish that they alone are the ones their child should attach to in their new life, which can seem harsh to grandparents, friends and other caregivers. Parents must be the ones to meet all their child’s needs for physical affection, emotional comfort, and basic needs like food. No one else, for six months, we were told. It was not a threat, to heed or feel guilty about (there are circumstances outside of our control). It was advice from those who know how delicate and difficult it can be for humans to form new secure attachments, to trust and live as though this new relationship will be forever. To do that, we need our focus narrowed down to only one or two people, until it sticks. There will be developmental stages, especially in the teenage years, when everyone questions their identity and belonging, but the goal we keep in front of us as adoptive parents is to pay attention to nurturing attachment and never to sow any seeds of doubt about the permanence of our family. As Paul writes, when we cry “Abba! Father!” it is the spirit bearing witness to our trust that God our Parent hears and will respond to us. Every single time. This is a permanent, secure attachment. Yet even with God, it takes time to develop attachment when we have been abandoned by others.

As I began my first solo pastorate, the contradictory advice from colleagues was rampant. Start out in the way you intend to continue. Carry on where the interim pastor left off. Remember: you only have six months to change everything that needs changing, while they forgive you because it is a “honeymoon period.” Also, do not change anything for the first year, minimum. In reality, the initial challenge is to figure out with whom we are working and how we will build trust with them. One of my first actions as pastor was to attend a women’s retreat, where I met all the “mothers of the church” at once. One of the West African women with a gregarious personality seemed to me like a main figure in the group, because she was so vocal. She volunteered information about many of her peers, and I began thinking: “She will be so helpful to me! I will consult with her and learn a great deal.” I remembered her name and face, while others blended together in my memory. Yet I did not see her in church for nearly a month after that; she was not as much of an insider as I had guessed. I gradually learned that one of the least vocal women was the quietly dependable and revered leader among the African women of the congregation. I should not have assumed that figuring everyone out would be simple or possible. I also waffled quite a bit between trusting my instincts and doing what I was told was culturally expected by the West African church members. Stepping into this central role was such a privilege and a huge puzzle. How do we become the central figure everyone can depend on, knowing that someday the center has to hold without us?

Jesus most certainly struggled with this. His disciples were arguing about sitting at his right and left hand, when his face was set on Jerusalem, and he was trying to prepare them to go on without him. As any self-aware caregiver, Jesus knew that he was the center of the family they had formed, for each and every one of his disciples. Yet he would not always physically be there to hold them together. “Come and follow me. I will make you fish for people,” he invited. Perhaps all some of them heard was “follow me.” When we are new to the family, tuning into that primary relationship until it is firmly established is critical. Until we can trust the One, we are not much good at radiating the loving purpose of our family out to others. I bet Jesus’s followers functioned as if Jesus was the “president.” They may not have depended on him for everything, with meals and lodging likely arranged by the women, but for advice and reassurance and settling disputes and empowerment to do hard things and validation of being special and beloved, they likely turned to Jesus. He was the center of the family, like a mother.

A lot of a mother’s time building trust is spent doing not much at all, or what seems like not much. We spend an inordinate amount of time meeting basic needs: feeding, dressing, and soothing. Yet while we are doing these things, are we silent? No, of course not. We are talking, making eye contact, noticing things about our children’s bodies, asking about what is going on with them. We are practicing the care we hope our children will someday give others and teaching them how members of our family respond to hurt. Jesus’s early followers—men and women—had lots of time with Jesus. The most notable incidents were remembered, retold, and eventually written down. Yet there were most certainly many mundane ordinary days that strengthened their bonds of trust. We like to focus on Jesus as otherworldly and therefore perfect, but he was also fully human, so his “children” in the faith probably also saw him cranky, tired of being needed by everyone, really looking for some help over here, and frustrated that they hadn’t become independent yet.

There is so much touch involved in caregiving: carrying, holding hands, embracing, and rubbing someone’s back as they calm down or fall asleep. It is astonishing how abruptly after reaching Mama’s arms an infant can turn off the tears. Getting a couple to hold hands for mutual support during marriage therapy may change the dynamic significantly. Jesus uses the potent balm of touch among his closest “chosen family” and many others, all children of God. If Jesus feels the power go out of him as a hemorrhaging woman touches his garment, then he probably—like a mother accustomed to small hands reaching for her—recognizes that touch is a caregiving superpower. Jesus takes a young girl’s hand, and thus raises her from the dead (Mark 5:41–42). He commands his disciples: “Let the little children come to me, for it is to such as these that the kingdom of heaven belongs,” and by embracing them smashes cultural norms that devalue children until they are of an age to help support the family. Jesus hands Peter the fish he has cooked himself, on the beach after his resurrection. I imagine Jesus supporting the hand that takes it with a lingering touch, pressing the wounds from the nails into Peter’s own flesh. When Thomas needs proof that the One in that locked room is indeed his beloved Jesus, he readily shows his scars, taking Thomas’s own hand to place it in his side. Like a mama showing her C-section scar, the body cannot lie: I am yours. The power of touch works in both directions. To feel our hearts beating together while we hug can build attachment within the caregiver too and strengthen our mutual sense of loving and being loved.

Another way to interpret that incident with the bleeding woman—depending on Jesus’s tone—might be exasperation: “Who is touching me now?” Clergy women talk among ourselves about being “touched out” from all the clinging of small children, hand-holding of elders, the handshaking/hugging line, and huddling up for youth group community-building exercises. When there are worshipers who give off sexually inappropriate vibes and insist on moving in for too-long hugs instead of taking the handshake offered, our bodies, with which we do our ministry, are at risk of feeling violated. Our bodies do not feel like our own, in real and vulnerable ways. This loss of personal space is magnified during pregnancy, when people might feel it is permissible to touch our expanding midsection. That identification with pastor as “part of our family” blurs their sense of decorum. Yet clergy mothers know that our availability builds the congregation’s confidence in the Word we preach and the love we are attempting to fortify in our faith community and family. Sometimes it is too much. We want nothing more than to get on a boat and float away from the crowds for a little regrouping. (We know they’ll be there whenever we get to the other side of the Sea of Galilee, but for just a little while, can we have a moment with fewer bodies reaching for us?)

Jesus’s powerful touch and ours are not just about granting miracles. Sometimes it can seem that way. People ask me to pray for them, although I know their prayers are just as effective as mine. I want to believe that miraculous healing is not why people are drawn to Jesus, or why they return to church during crises. The power of being trustworthy is holding people, witnessing and participating in their pain during the non-miraculous times. Remember when Jesus said, “The Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head”? He lived an itinerant, uncertain life in solidarity with our precarious lives. His physical body was touched to the point of death, until he was lifted up by God to new life.

Jesus’s body was a significant part of his ministry of presence, building trust. But his words are most certainly trustworthy, too. They tell the truth about us, both painful and reassuring. When speaking with the Samaritan woman at the well (John 4), Jesus earns her trust by telling the truth about her marital history, which turns her into an evangelist for Jesus, the “living water.” In the upper room during Holy Week, Jesus honestly identifies which of his disciples will betray him, then delivers to even Judas Iscariot his life-changing words that Jesus is giving up his own body and blood for us. His words do more than communicate; they establish a way people may come into direct contact with God on earth. His words are also actions, which can be trusted and should be repeated by us in remembrance of him.

From the start, caregivers telling the truth to us, about us, matters. Before we become teenagers trying to define ourselves against our parents, the trustworthiness of our central parenting figure sets the stage for how our relationship can recover from that inevitable defiance. For example, it matters that we talk to our kids about sex and how babies are made in age-appropriate ways from a young age, using the correct name for body parts. It is not the stork. If we are honest from the beginning, sharing bits of truth in matter-of-fact ways as they grow, what they are not able to process will go over their heads and what they need to hear, they will. What the children will most certainly understand is that they can talk to us about anything, especially the subjects that become fundamental parts of our identities.

For our children and within our congregations, two of the most crucial topics to be honest about are death and grief. Death is coming for us all, and even though we hope for the resurrection of the dead with Christ, grief is mighty powerful. We will all experience many kinds of loss, some of it accompanied by guilt, some by the pain of victimhood. More than anything, we need a God who will tell us the truth about that, weep for real, beg for that cup to be taken from him, and demonstrate that, even on the other side, wounds are still there. That is truth telling I can trust. Children of God do not need empty promises or the stifling attempts at comfort that prove the other person is uncomfortable such as, “Don’t cry” or “God will make something good out of this.” We need caregiving that tells the truth and is comforting because someone is in solidarity with us.

I was a teaching assistant for a freshman core class that encompassed Theology 101 among other subjects. I witnessed college freshmen who were so disturbed by reading the Bible and realizing for the first time that there are, in fact, two different creation accounts in Genesis that one young woman actually developed a kind of tic, a shiver. We talked about the different sources in putting the scriptures together. The assertion that those words were written in a way other than by holy dictation broke her. The faith community that raised her had reinforced repeatedly that the Bible was the unquestionable Word of God, so to read it as literature or more specifically as a compilation of multiple faithful sources raised serious questions about her home congregation’s trustworthiness.