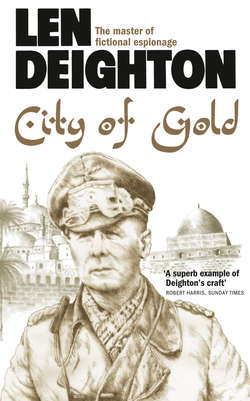

Читать книгу City of Gold - Len Deighton - Страница 9

1

ОглавлениеCairo: January 1942

‘I like escorting prisoners,’ said Captain Albert Cutler, settling back and stretching out his legs along the empty seats. He was wearing a cream-coloured linen suit that had become rumpled during the journey. ‘When I face a long train journey, I try and arrange to do it.’

He was a florid-faced man with a pronounced Glasgow accent. There was no mistaking where he came from. It was obvious right from the moment he first opened his mouth.

The other man was Jimmy Ross. He was in khaki, with corporal’s stripes on his sleeves. He was that rarest of Scots, a Highlander: from a village in Wester Ross. But they’d tacitly agreed to bury their regional differences for this brief period of their acquaintanceship. It was Ross’s pocket chess set that had cemented their relationship. They were both at about the same level of skill. During the journey they must have played fifty games. At least fifty. And that was not counting the little demonstrations that Cutler had pedantically given him: openings and endings from some of the great games of the chess masters. He could remember them. He had a wonderful memory. He said that was what made him such a good detective.

It was an old train, with all the elaborate bobbins and fretwork that the Edwardians loved. The luggage rack was of polished brass with tassels at each end. There was even a small bevelled mirror in a mahogany frame. In the roof there was a fan that didn’t work very well. According to the wind and the direction of the train, the ventilator emitted gusts of sooty smoke from the locomotive. It did it now, and Ross coughed.

There came the sounds of passengers picking their way along the corridor. They stumbled past with their kit and baggage and rifles and equipment. They spoke in the tired voices of men who have not slept; the train was very crowded. They couldn’t see in. All the blinds were kept lowered on this compartment, but there was enough sunlight getting through the linen. It made a curious shadowless light.

‘Why would you like that?’ said Jimmy Ross. ‘Escorting prisoners. Why would you like that?’ He had a soft Scots accent that you’d only notice if you were looking for it. Jimmy Ross was slim and dark and more athletic than Cutler, but both men were much the same. Their similarities of upbringing – bright, working-class, grammar school graduates without money enough to go up to university – had more than once made them exchange looks that said, There but for the grace of God go I, or words to that effect.

‘I wear my nice civvy clothes, and I get a compartment to myself. Room to put my feet up. Room to stretch out and sleep. No one’s bothered us, have they? I like it like that, especially on these trains.’ Cutler tugged at the window blind and raised it a few inches to look out at the scenery. On the glass, as on the windows to the corridor, there were large gummed-paper notices that bore the royal coat of arms, the smudged rubber stamps, the scrawled signatures of a representative of the provost marshal, and the words RESERVED COMPARTMENT in big black letters. No one with any sense would have intruded upon them.

Bright sunlight came into the compartment as he raised the blind. So did the smell of excrement, which was spread on the fields as fertiliser. Cutler blinked. Outside, the countryside was green: dusty, of course, like everything in this part of the world, but very green. This was Egypt in winter: the fertile region.

The train clattered and groaned. It was not going fast; Egyptian trains never went fast. Scrawny dark-skinned men, riding donkeys alongside the track, stared back at them. In the fields, women were bending to weed a row of crops. They stepped forward, still in line, like soldiers. ‘A long time yet,’ pronounced Cutler, looking at his watch. He lowered the blind again. When the train reached Cairo the two men would part. Cutler, the army policeman, would take up his nice new appointment with Special Investigation Branch Headquarters, Middle East. Jimmy Ross would be thrown into a stinking army ‘glasshouse’. He knew he could expect a very rough time while awaiting court-martial. The military prison in Cairo had a bad reputation. After he’d been tried and found guilty, he might be sent to one of the army prisons in the desert. Ross smiled sadly, and Cutler felt sorry for him. It hadn’t been a bad journey; two Scotsmen can always find something in common.

‘Have you never been attacked?’ said Ross.

‘Attacked?’

‘By prisoners. Don’t men get desperate when they are under arrest?’

Cutler chuckled. ‘You wouldn’t hurt me, would you?’ There was not much difference in their ages or their builds. Cutler wasn’t frightened of the prisoner. Potbellied as he was, he felt physically superior to him. In Glasgow, as a young copper on the beat, he’d learned how to look after himself in any sort of rough-house.

‘I’m not a violent man,’ said Ross.

‘You’re not?’ Cutler laughed. Ross was charged with murder.

Reading his thoughts, Jimmy Ross said, ‘He had it coming to him. He was a rotten bastard.’

‘I know, laddie.’ He could see that Jimmy Ross was a decent enough fellow. He’d read Ross’s statement, and those of the witnesses. Ross was the only NCO there. The officer was an idiot who would have got them all killed. And he pulled a gun on his men. That was never a good idea. But Cutler was tempted to add that his victim’s being a bastard would count for nothing. Ross was an ‘other rank’, and he’d killed an officer. That’s what would count. In wartime on active service they would throw the book at him. He’d be lucky to get away with twenty years’ hard labour. Very lucky. He might get a death sentence.

Jimmy Ross read his thoughts. He was sitting handcuffed, looking down at the khaki uniform he was wearing. He fingered the rough material. When he looked up he could see the other man was grimacing. ‘Are you all right, captain?’

Cutler did not feel all right. ‘Did you have that cold chicken, laddie?’ Cutler had grown into the habit of calling people laddie. As a police detective-inspector in Glasgow it was his favoured form of address. He never addressed prisoners by their first names; it heightened expectations. Other Glasgow coppers used to say sir to the public but Cutler was not that deferential.

‘You know what I had,’ said Ross. ‘I had a cheese sandwich.’

‘Something’s giving me a pain in the guts,’ said Cutler.

‘It was the bottle of whisky that did it.’

Cutler grinned ruefully. He’d not had a drink for nearly a week. That was the bad part of escorting a prisoner. ‘Get my bag down from the rack, laddie.’ Cutler rubbed his chest. ‘I’ll take a couple of my tablets. I don’t want to arrive at a new job and report sick the first minute I get there.’ He stretched out on the seat, extending his legs as far as they would go. His face had suddenly changed to an awful shade of grey. Even his lips were pale. His forehead was wet with perspiration, and he looked as if he might vomit.

‘It’s a good job, is it?’ Jimmy Ross pretended he could see nothing wrong. He got to his feet and, with his hands still cuffed, got the leather case. He watched Cutler as he opened it.

Cutler’s hands were trembling so that he had trouble fitting the key into the locks. With the lid open Ross reached across, got the bottle and shook tablets out of it. Cutler opened his palm to catch two of them. He threw them into his mouth and swallowed them without water. He seemed to have trouble getting the second one down. His face hardened as if he was going to choke on it. He frowned and swallowed hard. Then he rubbed his chest and gave a brief bleak smile, trying to show he was all right. He’d said he often got indigestion; it was the worry of the job. Ross stood there for a moment looking at him. It would be easy to crack him over the head with his hands. He could bring the steel cuffs down together onto his head. He’d seen someone do it on stage in a play.

For a moment or two Cutler seemed better. He tried to overcome his pain. ‘I’ve got to find a spy in Cairo. I won’t be able to find him, of course, but I’ll go through the motions.’ He closed the leather case. ‘You can leave it there. I will be changing my trousers before we arrive. That’s the trouble with linen; it gets horribly wrinkled. And I want to look my best. First impressions count.’

Ross sat down and watched him with that curiosity and concerned detachment with which the healthy always observe the sick. ‘Why won’t you be able to find him?’ Being under arrest had not lessened his determined hope that Britain would win the war, and this fellow Cutler should be trying harder. ‘You said you were a detective.’

‘Ah! In Glasgow before the war, I was. CID. A bloody good one. That’s why the army gave me the rank straight from the force. I never did an officer’s training course. They were short of trained investigators. They sent me to Corps of Military Police Depot at Mytchett. Two weeks to learn to march, salute, and be lectured on military law and court-martial routines. That’s all I got. I came straight out here.’

‘I see.’

Cutler became defensive. ‘What chance do I stand? What chance would anyone stand? They can’t find him with radio detectors. They don’t think he’s one of the refugees. They’ve exhausted all the usual lines of investigation.’ Cutler was speaking frankly in a way he hadn’t spoken to anyone for a long time. You could speak like that to a man you’d never see again. ‘It’s a strange town, full of Arabs. This place they’re sending me to: Bab-el-Hadid barracks – there’s no one there … I mean there are no names I recognise, and I know the names of all the good coppers. They are all soldiers.’ He said it disgustedly; he didn’t think much of the army. ‘Conscripts … a couple of lawyers. There are no real policemen there at all; that’s my impression anyway. And I don’t even speak the language. Arabic; just a lot of gibberish. How can I take a statement or do anything?’ Very slowly and carefully Cutler swung his legs round so he could put his feet back on the floor again. He leaned forward and sighed. He seemed to feel a bit better. But Ross could see that having bared his heart to a stranger, Cutler now regretted it.

‘So why did they send for you?’ said Ross.

‘You know what the army’s like. I’m a detective; that’s all they know. For the top brass, detectives are like gunners or bakers or sheet-metal workers. One is much like the other. They don’t understand that investigation is an art.’

‘Yes. In the army, you are just a number,’ said Ross.

‘They think finding spies is like finding thieves or finding lost wallets. It’s no good trying to tell them different. These army people think they know it all.’ A sudden thought struck him. ‘Not a regular, are you?’

‘No.’

‘No, of course not. What did you do before the war?’

‘I was in the theatre.’

‘Actor?’

‘I wanted to be an actor. But I settled for stage managing. Before that I was a clerk in a solicitor’s office.’

‘An actor. Everyone’s an actor, I can tell you that from personal experience,’ said Cutler. He suddenly grimaced again and rubbed his arms, as if at a sudden pain. ‘But they don’t know that … Jesus! Jesus!’ and then, more quietly, ‘That chicken must have been off…’ His voice had become very hoarse. ‘Listen, laddie… Oh, my God!’ He’d hunched his shoulders very small and pulled up his feet from the floor, like an old woman frightened of a mouse. Then he hugged himself; with his mouth half open, he dribbled saliva and let out a series of little moaning sounds.

Jimmy Ross sat there watching him. Was it a heart attack? He didn’t know what to do. There was no one to whom he could go for assistance; they had kept apart from the other passengers. ‘Shall I pull the emergency cord?’ Cutler didn’t seem to hear him. Ross looked up, but there was no emergency cord.

Cutler’s eyes had opened very wide. ‘I think I need…’ He was hugging himself very tightly and swaying from side to side. All the spirit had gone out of him. There was none of the prisoner-and-guard relationship now; he was a supplicant. It was pitiful to see him so crushed. ‘Don’t run away.’

‘I won’t run away.’

‘I need a doctor…’

Ross stood up to lean over him.

‘Awwww!’

Hands still cuffed together, Ross reached out to him. By that time it was too late. The policeman toppled slightly, his forehead banged against the woodwork with a sharp crack, and then his head settled back against the window. His eyes were staring, and his face was coloured green by the light coming through the linen blind.

Ross held him by the sleeve and stopped him from falling over completely. Hands still cuffed, he touched Cutler’s forehead. It was cold and clammy, the way they always described it in detective stories. Cutler’s eyes remained wide open. The dead man looked very old and small.

Suddenly Ross stopped feeling sorry. He felt a pang of fear. They would say he’d done it, he’d murdered this military policeman: Captain Cutler. They’d say he’d fed him poison or hit him the way he’d hit that cowardly bastard he’d killed. He tried to still his fears, telling himself that they couldn’t hang you twice. Telling himself that he’d look forward to seeing their faces when they found him with a corpse. It was no good; he was scared.

He stared down at the handcuffs. His wrists had become chafed. He might as well unlock them. That was the first thing to do, and then perhaps he’d get help. Cutler kept the key in his right-side jacket pocket, and it was easy to find. There were other keys on the same ring, including the little keys to Cutler’s other luggage that was in the baggage car. He rubbed his wrists. It was good to get the cuffs off. Cutler had been decent enough about the handcuffing. One couldn’t blame a man for taking precautions with a murderer.

With the handcuffs removed, Jimmy Ross felt different. He juggled the keys in the palm of his hand and on an impulse unlocked Cutler’s leather case and opened it. There were papers there: official papers. Ross wanted to see what the authorities had written about his case.

It was amazing what people carried around with them: a bottle of shampoo, a silver locket with the photo of an older woman, a silver-backed hairbrush, and a letter from a Glasgow branch of the Royal Bank of Scotland acknowledging that he’d closed his mother’s account with them. It was dated three months before. Now that the mail from Britain went round Africa, it was old by the time it arrived. A green cardboard file of papers about Cutler’s job in Cairo. ‘Albert George Cutler … To become a major with effect the first December 1941.’ So the new job brought him promotion too. Acting and unpaid, of course; promotions were usually like that, as he knew from working in the orderly room. But a major; a major was a somebody.

He looked at the other papers in the case but he could find nothing about himself. Travel warrant, movement order, a brown envelope containing six big white five-pound notes and seven one-pound notes. A tiny handyman’s diary with tooled leather cover and a neat little pencil in a holder in its spine. Then he found the amazing identity pass that all the special investigation staff carried, a pink-coloured SIB warrant card. He’d heard rumours about these passes but he didn’t think he’d ever hold one in his hands. It was a carte blanche. The rights accorded the bearer of the pass were all-embracing. Captain Cutler could wear any uniform or civilian clothes he chose, assume any rank, go anywhere and do anything he wished.

A pass like this would be worth a thousand pounds on the black market. He looked at the photograph of Cutler. It was a poor photograph, hurriedly snapped by some conscripted photographer and insufficiently fixed so that the print was already turning yellow. It was undoubtedly Cutler, but it could have been any one of a thousand other men.

It was then that the thought came to him that he could pass himself off as Cutler. Cutler’s hair was described as straight, and Ross’s hair was wavy, but with short army haircuts there was little difference to be seen. When alive Cutler had been red complexioned, while Ross was tanned and more healthy looking. But the black-and-white photograph revealed nothing of this. Their heights were different, Cutler shorter by a couple of inches, but it seemed unlikely that anyone would approach him with a tape measure and check it out. He stood up and looked in the little mirror, and held in view the photo to compare it. It was not a really close likeness, but how many people asked a military police major to prove his identity? Not many.

Then his heart sank as he realised that the clothes would give them away. He’d have to arrive wearing the white linen suit.

Changing clothes would be too much; he couldn’t go through with that. He opened Cutler’s other bag. It was a fine green canvas bag of the sort that equipped safaris. Inside, right at the top, was the pair of white canvas trousers. Ross made sure that the blinds were down and then he changed into the trousers. Damn! They were a couple of inches too short.

Then he had another idea. He’d get off the train in his corporal’s uniform and use the SIB pass. But that would leave the corpse wearing mufti. Would they believe that an army corporal would arrive in civilian clothes? Why not? They’d arrested Ross in the corporal’s uniform he was wearing. Had he been wearing a civilian suit, they would not have equipped him with a uniform for the journey, would they?

He looked at himself again. Certainly those white trousers would not do. With an overcoat he might have been able to let the waist of the trousers go low enough to look normal. But without an overcoat he’d look like a circus clown. Shit! He could have sobbed with frustration.

Well, it was the corporal’s uniform or nothing. He looked at himself in the little mirror and tried imitating Cutler’s Glasgow accent. It wasn’t difficult. To his reflection he said, ‘This is the chance you’ve always prayed for, Jimmy. The star has collapsed and you’re going on in his place. Just make sure you get your bloody lines right.’

It was worth a try. But he wouldn’t need the voice. All he wanted to do was just get off the train, and disappear into the crowds. He’d find some place to hide for a few days. Then he’d figure out where to go. In a big town like Cairo he’d have a chance to get clear away. Rumour said the town was alive with military criminals and deserters and black-market crooks. What about money? If he could find some little army unit in the back of beyond, he’d bowl in and ask for a ‘casual pay parade’. He knew how that was done; transient personnel were always wanting pay. Meanwhile, he had nearly forty pounds. In a place like Cairo that would be enough for a week or two: maybe a month. He’d have to find a hotel. Such places as the YMCA and the hostels and other institutions were regularly checked for deserters. The real trouble would be the railway station and getting past the military police patrols. Those red-capped bastards hung around stations like wasps around a jam jar. He had Cutler’s pass, but would they believe he was an SIB officer? More likely they’d believe that he was a corporal without a leave pass.

He sat down and tried to think objectively. When he looked up he was startled to find the dead eyes of Cutler staring straight at him. He reached out and gently touched his face, half expecting the dead man to smile or speak. But Cutler was dead, very dead. Damn him! Jimmy Ross got up and went to another seat. He had to think.

About five minutes later he started. He had to be very methodical. First he would empty his own pockets, and then he would empty Cutler’s pockets. They had to completely change identity. Don’t forget the signet ring his mother had given him; it would be a shame to lose it but it might be convincing. He’d have to strip the body. He must look inside shirts and socks for name tapes and laundry labels too. Officers didn’t do their own washing: they were likely to have their names on every last thing. There was an Agatha Christie yarn in which the laundry label was the most incriminating clue. One slip could bring disaster.

As the train clattered over the points to come into Cairo station, Ross undid the heavy leather strap that lowered the window. Everyone else on the train seemed to have the same idea. There were heads bobbing from every compartment. The smell of the engine smoke was strong but not so powerful as to conceal the smell of the city itself. Other cities smelled of beer or garlic or stale tobacco. Cairo’s characteristic smell was none of those. Here was a more intriguing mix: jasmine flowers, spices, sewerage, burning charcoal, and desert dust. Ross leaned forward to see better.

He need not have bothered. They would have found the compartment; they were looking for the distinctive RESERVED signs. There were two military policemen complete with red-topped caps and beautifully blancoed webbing belts and revolver holsters. With them there was a captain wearing his best uniform: starched shirt, knitted tie and a smart peaked cap. A military police officer! The only other time he’d ever seen one of those was when he was formally arrested.

It was the officer who noticed Ross leaning out of the window of the train and called to him. ‘Major Cutler! Major Cutler!’

The train came to a complete halt with a great burst of steam and the shriek of applied brakes. The sounds echoed within the great hall.

‘Major Cutler?’ The officer didn’t know whether to salute this man in corporal’s uniform.

‘Yes. I’m Cutler. An investigation. I haven’t had a chance to change,’ said Ross, as casually as he could. He was nervous; could they hear that in his voice? ‘I’m stuck with this uniform for the time being.’ He wondered whether he should bring out his identity papers but decided that doing so might look odd. He hadn’t reckoned on anyone’s coming to meet him. It had given him a jolt.

‘Good journey, sir? I’m Captain Marker, your number one.’ Marker smiled. He’d heard that some of these civvy detectives liked to demonstrate their eccentricities. He supposed that wearing ‘other ranks’ uniforms was one of them. He realised that his new master might take some getting used to.

Jimmy Ross stayed at the window without opening the train door. ‘We’ve got a problem, Marker. I’ve got a prisoner here. He’s been taken sick.’

‘We’ll take care of that, sir.’

‘Very sick,’ said Ross hastily. ‘You are going to need a stretcher. He was taken ill during the journey.’ With Marker still looking up at him quizzically, Ross improvised. ‘His heart, I think. He told me he’d had heart trouble, but I didn’t realise how bad he was.’

Marker stepped up on the running board of the train and bent his head to see the figure hunched in his corner seat. Civilian clothes: a white linen suit. Why did these deserters always want to get into civilian clothes? Khaki was the best protective colouring. Then Marker looked at his new boss. For a moment he was wondering if he’d beaten the prisoner. There was no blood or marks anywhere to be seen but men who beat prisoners make sure there is no such evidence.

Ross saw what he was thinking. ‘Nothing like that, Captain Marker. I don’t hit handcuffed men. Anyway he’s been a perfect prisoner. But I don’t want the army blamed for ill-treating him. I think we should do it all according to the rule book. Get him on a stretcher and get him to hospital for examination.’

‘There’s no need for you to be concerned with that, sir.’ Marker turned to one of his MPs. ‘One of you stay with the prisoner. The other, go and phone the hospital.’

‘He’s still handcuffed,’ said Ross who’d put the steel cuffs on the dead man’s wrists to reinforce his identity as the prisoner. ‘You’ll need the key.’

‘Just leave it to my coppers,’ said Marker taking it from him and passing it to the remaining red cap. ‘We’d better hurry along and sort out your baggage. The thieves in this town can whisk a ten-ton truck into thin air and then come back for the logbook.’ Marker looked at him; Ross smiled.

Ten billion particles of dust in the air picked up the light of the dying sun that afternoon, so that the slanting beams gleamed like bars of gold. So did the smoke and steam and the back-lit figures hurrying in all directions. Even Marker was struck by the scene.

‘They call it the city of gold,’ he said. There was another train departing. It shrieked and whistled in the background while crowds of soldiers and officers were fussing around the mountains of kitbags and boxes and steamer trunks that were piling up high on the platforms.

‘Yes, I used to know a poem about it,’ said Ross. ‘A wonderful poem.’

‘A poem?’ Marker was surprised to hear that this man was a devotee of poetry. In fact he was astonished to learn that any SIB major, particularly one who’d risen to this position through the ranks of the Glasgow force, would like any poem. ‘Which one was that, sir?’

Ross was suddenly embarrassed. ‘Oh, I don’t remember exactly. Something about Cairo’s buildings and mud huts looking like the beaten gold the thieves plunder from the ancient tombs.’ He’d been about to recite the poem, but suddenly the life was knocked out of him as he remembered that his own kitbag was there too. His first impulse was to ignore it, but then it would go to ‘Lost Luggage’ and they’d track it back to a prisoner named James Ross. What should he do?

‘I should have brought three men,’ said Marker apologetically as they stood near the baggage car, looking at the luggage. ‘I wasn’t calculating on us having to sort out your own gear.’

‘Just one more bag,’ said Ross. ‘Green canvas, with a leather strap round it. There it is.’ Then he saw the kitbag. Luckily it had suffered wear and tear over the months since his enlistment. The stencilled name ROSS and his regimental number had faded. ‘And the brown kitbag.’

‘Porter,’ called Marker to a native with a trolley. ‘Bring these bags.’ He kicked them with his toe. ‘Follow us.’ To his superior he explained, ‘You must always get one with a metal badge and remember his number.’ He politely took Cutler’s leather briefcase. ‘It’s not worth bringing a car here,’ explained Marker. ‘We’re in the Bab-el-Hadid barracks. It’s just across the midan.’

Marker kept walking, out through the ticket barrier, across the crowded concourse and the station forecourt. The porter followed. Once outside the station, there was all the bustle of a big city. It was the sort of day that Europeans relished. It was winter, the air was silky, and the sun was going down in a hazy blue sky.

So this was Cairo. Ross was looking around for a way of escape but Marker was determined to play the perfect subordinate. ‘You’ll find you’ve got a pretty good team,’ said Marker. ‘And what a brief! Go anywhere, interrogate anyone and arrest almost anyone. “You’re a sort of British Gestapo,” the brigadier told us the other day. The brigadier’s a decent old cove too; you’ll like him. He’ll support you to the end. All you have to worry about is catching Rommel’s spy.’

Ross grunted his affirmation.

Marker froze. Suddenly he realised that this probably wasn’t the way the army treated a newly arrived superior. And not the way to describe a brigadier. Marker had been the junior partner in a law office before volunteering for the army. It was the way he treated his colleagues back home, but perhaps this fellow Cutler was expecting something more formal and more military.

They walked on in silence, brushing aside hordes of people. All of them seemed to be selling something. They brandished trays upon which were arrayed shoelaces, flyswatters, sweet cakes, pencils and guidebooks. The great open space before the station was alive with peddlars. And there was Englishness too: little trees, neat little patches of flowers, and even green grass.

‘That’s the barracks,’ said Marker. ‘Not far now.’

In the distance, Ross saw a grim-looking crusader castle of ochre-coloured stone. The low rays of the sun caught the sandstone tower so that it too gleamed like gold.

Ross looked around. He didn’t want to go into the barracks; he wanted to get away. There were too many policemen in evidence for him to run. Half a dozen men of the Cairo force came riding past, mounted on well-groomed horses. The British army’s policemen were not to be seen on horses. With their red-topped peaked caps they stood in pairs, feet lightly apart and hands loosely clasped behind their backs. They were everywhere, and all of them were armed.

Back at the train compartment, the two MPs were waiting for the doctor to arrive. The elder of the two men assumed seniority. He wore First World War ribbons on his chest. He’d leaned into the compartment and spoken to the dead man a couple of times and got no response. Now he said, ‘Dead.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Stone cold. In France I saw more dead men than you could count.’

‘What will we do?’

‘Do? Nothing. The officer says he’s sick; he’s sick. Let the doctor decide he’s dead. That’s what he’s paid for, ain’t it?’

He got down from the compartment, and they both stood alongside the open train door and waited.

The younger red cap did not relish the prospect of moving the body. He changed the subject and said to his companion, ‘I reckon that’s the one they’ve sent to take over from that major with the big walrus moustache.’

‘Well, that bastard lost a pip and was booted out to Aden or somewhere.’

They watched a civilian coming through the crowd. They hoped it might be the doctor, but when he stopped for a moment at the sight of the snake-charmers they knew it couldn’t be. Only tourists and newcomers stopped to see the magicians and snake charmers and acrobats. ‘I heard the new bloke was coming today. Some sort of detective from Blighty, according to what the rumours say.’

‘Well, that one won’t last long,’ said the elder man. ‘He obviously doesn’t know Cairo from a hole in the ground. How’s he going to start finding a bloody spy here?’

‘Nice disguise though.’

‘The corporal’s uniform?’

‘Yes, the corporal stunt.’

‘You get the idea, don’t you?’ said the elder man bitterly. ‘If that Captain Marker hadn’t brought us over here to sort him out, that bastard would have ambled over to the barracks, and if he’d got through improperly dressed, and no one asking him for his leave pass, we’d all be for the high jump for dereliction of duty and suchlike.’

‘I suppose. Where’s that bloody doctor?’ said the young one. He’d phoned. ‘They said straightaway. We’re back on duty tonight again, aren’t we?’

‘Too right. It’s El Birkeh tonight, my old pal. I hope you’re feeling up to it.’

‘I dread that rotten poxy place. It stinks. I’ve asked to go back on traffic duties. I’m sick of patrolling whorehouses.’

Ross had been completely accepted in his corporal’s uniform. Marker showed no suspicion at all. But there just seemed to be no way of escaping his amiable friendliness.

When they got to the gate of Bab-el-Hadid barracks there was an armed sentry there. The porter dumped the bags and Marker paid him off. Ross offered him his identity card but the sentry gave it no attention. His eyes were staring straight ahead as he gave the two men a punctilious salute.

‘The staff all know you are coming,’ explained Marker. He flipped open the special card issued by SIB Middle East, so that his superior saw it. ‘Your pass is no use to you here. We don’t let people in and out of here with the ordinary passes and so forth, not even SIB people. We have our own identity cards. I think we should get you photographed today, sir, if you can spare the time. It’s difficult to keep the sentries on their toes unless we set an example.’

‘Yes, of course,’ said Ross.

‘And then you will have your new pass and identity document tomorrow.’ He led the way up the stone steps.

‘Very efficient,’ said Ross. His voice echoed. This place was just like an ancient castle, but no doubt the coolness of the stone would be welcome when summer came.

Marker didn’t respond to the compliment. ‘The routine is to close all the Cairo offices between one PM and five PM. I’ve asked your staff to be at their desks early. I thought you might like to meet them. Then you could cut away and see your quarters.’

‘I’ll take your advice, Marker.’

‘Unless you want to go through the files, sir. I have told your clerk – if you decide to keep the same clerk as your predecessor – to have all the current files ready for you to examine. Or I can take you through them verbally.’

‘Are you always like this, Marker?’

‘Like what, sir?’

‘Super bloody efficient.’

Marker looked at him trying to decide if he was being sarcastic. He couldn’t tell. This new man knew how to keep an inscrutable face. ‘In civvy street I worked for myself, sir.’

‘You’re beginning to give me an inferiority complex, Marker. Do you know that?’

‘I’m sorry, sir.’ How far was Major Cutler joking? It was hard to know. They were walking along the open balcony overlooking the parade ground. A dozen red caps were being paraded and inspected before going off on their patrols through the streets of the town.

‘This way, sir. This is your office.’

The department that Cutler had been assigned to take over had its offices on this floor. This part of the building was only one room deep. The offices that were reached from the balcony overlooked the midan and the railway station beyond it.

They were all lined up waiting for him: privates, corporals and a sergeant plus four radio-room staff and their corporal in charge. There was even a cunning-looking old soldier who was assigned to be his clerk.

‘Organise a photographer right away,’ said Marker to one of the clerks. ‘Identity photo for the major, double quick.’

‘We’ll get to know each other soon enough,’ said Ross trying to remember other clichés he’d come across during his duties in the orderly room. Marker introduced each of them and described their duties, their accomplishments and, where applicable, their previously held civilian jobs. None of them were ex-policemen. Poor old Cutler had guessed right about that.

‘Is that everyone?’

Marker hesitated.

‘Well, is it?’ said Ross.

‘There is only one member of your staff not here yet,’ said Marker. ‘It’s a female clerk: Alice Stanhope. I’m sure she’ll be here any minute.’

‘Where is she?’

‘She went to see her mother in Alexandria.’

‘Is she sick?’

‘Her mother? No. No, not as far as I know.’

‘Why isn’t she at work then?’

Marker hesitated. It was difficult to explain about Alice Stanhope. ‘Her mother … that is to say her family are good friends with the brigadier. That’s really how she came to be working here.’

‘I see.’

‘Oh, don’t get me wrong, sir. Alice Stanhope is a highly intelligent young woman. She speaks several languages and knows more about this wretched country than any other European I’ve met.’

‘But?’

‘Well, her mother knows everyone. I mean everyone.’ He went to the door and looked over the balcony. Then he came back. ‘Yes, I thought that was her car. It’s an MG sports car, I recognised the sound of the engine.’

‘Do you mean to say she parks her car on the parade ground?’ said Ross incredulously.

‘Her mother arranged it with the brigadier,’ said Marker. In a way Marker enjoyed explaining the situation to his boss, just to watch his face.

‘I can’t wait to meet her,’ said Ross.

‘You won’t be disappointed,’ said Captain Marker.

He guessed of course that the big surprise was yet to come, so he was watching very carefully when Alice Stanhope came down the exterior balcony and swung in through the door. ‘I’m so sorry I’m late, sir,’ she said. Then, remembering she should have saluted, she came to attention and put her hat back on.

‘That’s quite all right,’ said Ross. Until that moment he’d firmly intended to leave his quarters that evening and disappear, thanking his lucky stars for preserving him. Now his plans, and indeed his life, changed. He would have to come back to the office tomorrow.

Alice Stanhope was the most beautiful woman he’d ever seen. He must see her again, if only just once.