Читать книгу Close-Up - Len Deighton - Страница 11

4

ОглавлениеOf course he romances, but an impressionable person of his sort really believes in his fabrications. We actors are so accustomed to embroider facts with details drawn from our own imaginations, that the habit is carried over into ordinary life. There, of course, the imagined details are as superfluous as they are necessary in the theatre.

C. Stanislavsky, An Actor Prepares

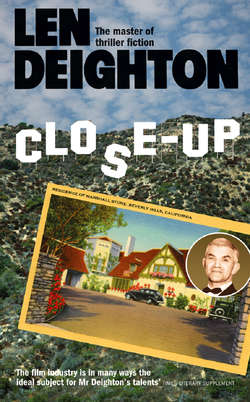

The unit publicist on Stool Pigeon sent me the biography they were using for Marshall Stone. It was printed on duplicating paper. Most of the first sheet was taken up by a letterhead design in which three soldiers and a girl fought their way through an Aubrey Beardsley jungle that had already overgrown the address and telephone number. Although a small clearing had been chopped for Edgar Nicolson’s name.

Edgar Nicolson Productions for Koolman International presents

Stool Pigeon starring Marshall Stone

Director: Richard Preston

Introducing: Suzy Delft.

MARSHALL STONE. A brief biography.

Marshall Stone was born in London. In a family that traditionally supplied its sons to the theatre and to the Army, Stone’s dilemma as an only child was resolved when war interrupted his studies at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art.

After the war he auditioned for Robert Atkins at Stratford and was so disappointed at being turned down that he toured South Africa with a company that did light comedy with music in its repertory, as well as a detective play and a farce. ‘It was a lunatic asylum,’ said Stone afterwards, ‘but we never stopped laughing in spite of the miseries and the hard work of it all.’ When he returned to England he joined the Birmingham Rep. His performance as Fortinbras in Hamlet was singled out for critical praise but apart from this his season went unmarked. ‘I spent my whole time there in open-mouthed awe. Perhaps I took direction too slavishly, for I never recognized anything of myself in the roles I played.

‘After getting into Birmingham – which had long been my ambition – I believed that the world was at my feet. I was wrong. After Birmingham I was turned down for three London parts. For a year I took anything I could get, including some TV work.’

In 1948 he was offered Lysander in a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that was to be staged in New York. They were actually in rehearsals when a network cutback caused the whole production to be scrapped. He stayed in New York and got a small part in an experimental group’s production of Brecht and eked out his finances with odd jobs on TV. He was in a restaurant in New York when he was seen by a Hollywood producer who screen-tested him for Last Vaquero, the film that brought him world-wide acclaim and broke box-office records in many countries from Japan to Italy.

In the following two years he starred in three Hollywood films, as well as creating his memorable Master Builder on the London stage and the exciting Tristram Shandy, Gent that was written for him to do at the Edinburgh Festival. No theatrical event of the nineteen-fifties was more important than Marshall Stone’s Hamlet. Gielgud himself called it ‘a miracle of discovery’.

Since that time Marshall Stone has divided his work between the stage and screen, as well as financing some avant-garde productions in Paris and doing a series of poetry readings for the BBC Third programme.

If there is one certain thing about the career of Marshall Stone, it is that no one can be certain what he will do next, except that it will be important, highly professional and never, never boring.

It was a good piece of publicity. But for those of us in never-never-boring-land who had learned to interpret avant-garde as disastrous, and exciting as unrehearsed, it left only the radio poetry, an assorted collection of forgettable films, Hamlet and The Master Builder.

The fact that the Ibsen performance had been superb and his Hamlet even better made the whole thing more, not less, depressing for me.

Listed under the biography were his films. Last Vaquero was at the top, but the compilation had omitted some of his worst flops including Tigertrap which, after its panning in New York, had been shelved until this week.

Even so, the achievements of Stone were remarkable and it would be a foolish historian who wrote of the postwar theatre without acknowledging his contribution. That he’d neglected the stage since Hamlet and contented himself with countless disappointing films didn’t obscure the dazzling talent that could be discerned in every performance he gave. As Scofield followed in the steps of Gielgud, so could Stone have followed Olivier. It still wasn’t too late; it was simply very unlikely.

In the same envelope there was the call-sheet for Stool Pigeon. The unit was on location outside Wellington Barracks.

Dear Peter Anson,

For the next three days Mr Marshall Stone will be working at Tiktok Sound Recording Studios in Wardour Street. He will be pleased to see you at any time you care to drop in.

Yours sincerely,

BRENDA STAPLES,

Publicity Secretary

No wonder schizophrenia was an occupational hazard among actors. At any time an actor might be doing publicity for a film that was being premièred, recording for one in post-production, acting in a third, fitting costumes for a fourth while reading scripts to decide what will come next.

In the competitive spirit of all flacks the note didn’t say which film Stone was looping, but I guessed it was one about the Alaskan oil pipeline that had been recut half a dozen times due to arguments between Nicolson, the director and some of Koolman’s people.

I saw Stone’s Rolls outside Tiktok, parked with the impunity that only chauffeurs manage. Its dark glass concealed the interior, which made one wonder why Stone had gone to the trouble of getting a registration plate that contained his initials.

Usually the door of Tiktok was ajar but today it was locked, with a suspicious guardian who grudgingly permitted me inside. Only fifty yards of corridor separated Studio D from the door but I passed through a screen of secretaries, bodyguards, tea-bringers, overcoat holders, messengers, advisers and a bald man whose sole job it was to pay for refreshments for the whole ensemble and note each item in his tiny notebook. Even the man who answered the phone that Stone had commandeered was not the one who made calls on Stone’s behalf.

They were a curious assembly of shapes, sizes and ages, dressed as variously as a random crowd in a bus queue. Their only bond was the fealty they demonstrated to Stone, for homage must not only be paid but also be seen to be paid. In common they had the same expression of bored indifference that all servants hide behind. They used it to admit me and to reply to my ‘good mornings’. They would use it to take my coat and bring me coffee and politely acknowledge any joke I cared to make. And, if necessary, they would use it when they tossed me out of the door or repeated for the umpteenth time that Stone was not at home.

Stone had hired them under many different circumstances, and in some cases their employment was little more than an excuse for Stone’s charity. Valuable though they were as retainers, they were even more vital as an audience. They travelled with Stone providing the affection, scandals, jokes, flattery and feuds – arbitrated by Stone – that an Italian padrone exacted from his family. This was the world of Stone and, like the world which he portrayed on the screen, it was contrived.

When I finally penetrated Studio D, Marshall Stone was sitting in an Eames armchair alongside an antique occasional table, on which was set coffee and cakes with Copenhagen china and silver pots. Later I was to hear that the chair and all the trimmings were brought there in advance by his employees, whose job it was to scout all such places and furnish them tastefully.

I recognized Sam Parnell and his usual assistants. They were sitting in a glass booth surrounded by the controls of the recording equipment. They were drinking machine-made coffee from paper cups. The booth was lighted by three spotlights over the swivel chairs. Enough light spilled from them to see the six rows of cinema seats and Stone sitting at the front. Parnell’s voice came over the loudspeaker as I entered. ‘OK, Marshall. Ready when you are.’

Stone gave him the thumbs-up sign and handed his copy of Playboy to a man who would hold it open at the right place until it was needed again. On the screen of the dimmed room there appeared a scratched piece of film. It was a black and white dupe print of Silent Paradise. Carelessly processed, its definition was fuzzy and the highlights burned out. A blobby man in glaring white furs said, ‘It should be me that goes, the other men have wives and families. I have no one.’

Marshall Stone watched himself and listened to the guide tracks so that as the loop of picture came round again he could record the words in synchronization with his lips. The trouble with looping was that men on the tundra were likely to sound as if they had their heads inside biscuit tins. This film was not going to be an exception. Edgar Nicolson productions seldom were.

The picture began again, Stone said, ‘It should be me that goes, the other – no, sod. Sorry, boys, we’ll have to do it again.’ The screen flashed white, and by its reflected light Stone saw me standing in the doorway. Although one of his servants had announced my arrival he preferred to act as though it was a chance meeting.

We had exchanged banalities at parties and he’d given me a brief interview for the newspaper articles, but this was a meeting between virtual strangers. That however was not evident from the warmth of his welcome.

He came towards me smiling broadly as he took my hands in his. He delivered a salvo of one-word sentences, ‘Wonderful. Marvellous. Great. Super.’ Narrow-eyed, he watched the effect of them like an artillery observer. Then he adjusted the range and the fuse setting to hit instead of straddling. ‘Damned fit. And a superb suit. Where did you get that wonderful tan: I’m jealous.’ Perhaps because he told me the things he wanted to tell himself there was an artless sincerity in his voice.

‘You’re looking well yourself, Marshall,’ I responded. He gripped my hand. He was smaller, more wrinkled and more tanned than I remembered, but his voice had the same tough reedy tone that I’d heard in his films.

‘Are you having problems?’ I asked.

‘It’s the stutter, darling.’ He could say ‘darling’ with such virile aplomb that it became the most sincere and effective greeting that one man could use to another.

‘I see.’

‘I would never have used a hesitation if I’d guessed I’d be looping it.’ The joke was on him but he laughed.

‘The sound crew thought they could use the original track?’

‘They swore that they’d be able to, but I could hear the genny and so could everyone else. If we could hear it, then the mike could pick it up. I should have put my foot down. God knows, I’ve been in the business long enough to know about recordings. But a bloody actor must know his place, eh, Peter?’ He pulled a slightly anguished face – hollow cheeks and half-closed eyes – before letting it soften into a broad smile. Just as his speech was articulated with an actor’s care, so did all his gestures have a beginning, middle and an end. He shook his head to remove the smile. ‘Get Mr Anson a fresh pot of coffee and some of those flaky pastries, will you, Johnny.’

Another man helped me off with my coat. I said, ‘The publicity secretary said…’

‘Sure, Peter, she said you might look in. Sandy, take Peter’s coat.’ Yet a third man put my coat on a hanger and carried it away with either reverence or disgust, I could not be sure which. ‘Glad of someone to talk to,’ said Stone. ‘Bloody boring, doing these loops. Will it be a full-length book?’

‘Yes. About eighty thousand words and lots of photos. By the way, the publicity people will let me have plenty of film stills but I was wondering if you have any personal snapshots you could lend me. You know: school groups, holiday snaps, mother, father or wartime photos.’ He looked up and stared at me.

‘I was in the war,’ he said.

‘What did you do?’

He stared at me until I shifted uncomfortably. ‘What did you do in the war, Daddy?’

I laughed nervously. ‘You know what I did, Marshall. I sat on my arse in Hollywood.’

He sensed my discomfort. ‘Yes, I know. Why?’

I’d rehearsed the answer to that a million times, so I had it pat. ‘I’d saved thirty shillings a week to pay my fare to California. It wasn’t so easy to chuck it up when war was declared. It was May 1940 when finally I went up to Canada and volunteered.’

‘And?’

‘When that Army radiographer found an ankle fracture from schooldays had mended badly… I wasn’t exactly heartbroken. But I volunteered every six months for the rest of the war just to appease my conscience. The nearest I got to active duty was working with John Ford and Darryl Zanuck making a US Army film about venereal disease. That was my war, Marshall, how did yours go?’

‘I worked with a chap named Millington-Ash, a brigadier. He ended the war a major-general. On paper I think I was probably a lance-corporal.’

‘What kind of outfit was that?’

He smiled at me as if I’d made a social gaffe. ‘Put infantry.’

‘I’ll forget the whole thing if you like.’

‘Office work for the most part but they quoted the Official Secrets Act at me a couple of times – you know.’

‘You mean you were some sort of agent?’

He moved his head in the direction of the man bringing the silver pot of coffee and the cream pastries. He didn’t answer until the man had gone again. Even then he took the precaution of covering the microphone with his hand, in case it was alive. ‘Not for publication, Pete, my boy. We could both get into hot water.’

‘Subject closed.’

‘That’s the best. Now, tell me what your readers will want to know about me.’

It was a practical if unorthodox attitude to biography. For a moment I was unable to think of an answer. I knew what I believed to be the job of the biographer. I knew it to be a process of selection, of emphasis and the relationship between events and attitudes. Just as Toynbee had once dismissed the ‘one damn thing after another’ school of historians, so I believed that a man’s activities were only a means to an end. A biography must show what a man is, rather than what he does. But to emphasize the influence that a writer had upon a finished life story was a dangerous thing to explain to Stone. Tactfully, I said, “They’d probably like to know what your life is like. They’d like to share your pleasures and your disappointments and learn something of your craft. They’d like to know how much of your success was luck and to what extent you created your own opportunity.’

‘Yes, yes, yes, and how much I earn and what I spend it on, what my house is like and who am I screwing.’

‘Not exactly,’ I said primly.

‘Listen, Peter. If you are going to have a go at me, you’d better be frank right from the start.’

‘Why would I want to do that?’

‘And why would some little creep grab me when I’m getting out of the Rolls this morning and tell me my last film was shit?’ He laughed to smother the spark of temper.

‘Did that happen?’

‘You get used to it.’ He sighed and smiled. ‘We all get them. Even the ones who are not actually insulting feel free to criticize your voice, your face, walk, dress, car, acting ability, et cetera. And they are amazed if you’re not grateful for it! There is a widespread illusion, Peter, that film stars lead protected lives and urgently need members of the public to stride up uninvited and start being frank with them.’

I nodded sympathetically.

‘Well, I don’t need it, darling. No one needs it. No one needs insults. You don’t need insults to your writing and I don’t need it for my acting.’

I guessed he was still smarting from the US reviews of Tigertrap. Too, he was girding his loins for the London showing. ‘That’s how it goes,’ I said.

‘We have enough doubts and fears already. God knows I’m my own most bitter critic…’ He laughed. He got up to do the next recording. During our talk he was always ready to do each recording as the technicians had the loop ready. Post-recording can kill an actor’s performance. Alone in a dark recording studio it’s not easy to reproduce the power and spontaneity of a performance created under the lights with other actors, and with a director to prod and interpret and stand ready with a vital potion of praise. But Stone was able to improve upon his guide track: he was able to make the words carry the emotion a step further. On the other hand I noticed the way he corrected the too forceful gestures in his performance by flattening the phrasing of the words. Stone was a pro and he completed each loop expertly and quickly.

‘I’m a professional too, Marshall,’ I warned him. ‘I’m not going to attack you but I’m not going to omit whole sections of your life to leave just a history of your successes. For instance, I don’t want to dwell upon your divorce but I can’t just forget that you were ever married. Neither of us can forget it.’

He looked relieved, if anything. ‘Poor Mary,’ he said. ‘How could you imagine I’d want to forget our life together. I owe her a lot, Peter, more than I can tell you. The divorce affected her more than she will ever admit, even to you. Rejection can make any of us say bitter things that we don’t really mean. You must remember that when you talk with her.’ He stopped, and I saw in him a cruelty that I’d never suspected and at which Mary never did hint.

‘She’s a truly wonderful person,’ he added.

I said nothing. The masterful inactivity that is the working method of doctors, interrogators and journalists did not fail me.

He continued, ‘When a woman marries a man who is dedicated to an art, her first object is to find out how dedicated.’ He smiled as he remembered. ‘Mary saw my acting as a direct rival. She wanted me to be home early, only take jobs where we could be together and not talk too much about my work. Can you imagine? I was a struggling young actor. I would have signed a ten-year contract for a repertory company in Greenland. I was desperate to act.’ He laughed, mocking his foolishness.

‘I tried with Mary. I really tried. But when a woman wants to find out if she’s married a hen-pecked type of man she starts to peck. Jesus, the rows we had! Sometimes we threw things. Once we smashed every piece of china in the house and then she cut my face by throwing an egg beater at me. It was only this marvellous man I’ve got in Harley Street who saved me from being scarred for life. As it was, when Mary saw his bill she started another row.’ He poured more coffee for me. At first I had been angry with the way he talked of Mary, but then I realized that he was trying to disregard the fact that she was now my wife.

‘When I had this chance of going to Hollywood, I sent for Mary as soon as it was practical. I thought a new country would give us a chance of starting again. You know.’ He pinched the bridge of his nose and looked away. When he turned back to me I saw that a tear had formed in the corner of his eye. It was a jet-black teardrop coloured by the mascara that he used on his lashes.

I said, ‘I saw your Hamlet twice. I’ve never seen its match.’

He brightened. ‘Schtik,’ he said modestly.

‘Skill! Your Yorick speech: the second time I was waiting for it, but it was still as natural as an ad lib.’

‘I delivered the previous lines tight on cue. But just after starting the Yorick speech I let them think I’d dried.’

He picked up the milk jug and twisted it in his hands. ‘“Let me see. Alas, poor Yorick.”’ He stared at the jug as if trying to read his lines there. He turned his eyes to me, hesitated, and then spoke in the lightest of conversational tones, ‘“I knew him, Horatio; a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy; he hath borne me on his back a thousand times.”’ Stone smiled, as if he’d performed some puzzling party trick for an appreciative small child. He was happy to amuse me further. ‘“Where be your gibes now? your gambols? your songs? your flashes of merriment that were wont to set the table on a roar?”’

Stone put the jug down. ‘Schtik,’ he said, but he could not conceal his pleasure. I remembered the wonderful notices he’d got and the predictions that had been made about him. Few doubted that he’d turn his back on movies and the rewards of Hollywood. The London theatre cleared a space for him, the electricians readied his name in neon and theatre critics sharpened their superlatives, delighted that an errant player should discover the London stage to be the only true Mecca.

But the ‘fresh young genius’, the ‘modern Irving’, this ‘giant in a land of giants’ soon caught the plane back to California.

Stone caught my eye. ‘My prince was a fine fellow.’

I nodded. ‘It wasn’t schtik.’

‘No, it wasn’t.’

Marshall Stone did not go to lunch. He’d eaten none of the cream pastries, although after I’d eaten both of them he sent out for more, as if having them there to resist was important to him: but perhaps it was just hospitality. At lunchtime one of his men brought him a polished apple wrapped in starched linen, a piece of processed cheese from Fortnum’s and three starch-free biscuits. The recording boys took their allotted lunchtime and Stone sent his men away, so we were alone in the dim studio. It was then that he gave me a demonstration of his skill.

He had been talking about speech training and how poor his voice had been when he was a young actor. He quoted his piece from the Bible making the sort of mistakes he made then, and after that he gave it to me with everything he’d got. It was an impressive demonstration of speech training. His voice was held low and resonant, and his articulation was precise and clipped so that even his whispers could have been projected a hundred yards or more. There were no tricks to it: no lilting Welsh vowels or hard Olivier consonants. He didn’t point any lines or throw any away. He didn’t pause too long or try to surprise me with the use of the thorax. He just did everything he could to make the words themselves transcend the fact that they were too well known.

‘“To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven:

‘“A time to be born, and a time to die: a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted;

‘“A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up;

‘“A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

‘“A time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together; a time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;

‘“A time to get, and a time to lose; a time to keep, and a time to cast away;

‘“A time to rend, and a time to sew; a time to keep silence, and a time to speak;

‘“A time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace.”’

It was very good, and Stone was smart enough to follow it with a moment’s silence while he searched his pockets for a cigarette.

‘You’ve talked with Edgar?’ Stone offered me a cigarette.

‘Yesterday.’

‘He was with me when I did Last Vaquero.’

‘So he said.’

‘He had that business with the girl… did he tell you?’

‘Yes.’

‘It was rotten luck. And Edgar is a sweet man.’

‘He said it spoiled his chance in Last Vaquero.’

‘He played the thief.’

‘Was he in the running for the lead?’

Stone gave a good-natured chuckle. ‘Did he say that?’

‘He told me he had a chance at the lead, except that Bookbinder was frightened of the scandal when the girl committed suicide.’

‘He’s wonderful, that Edgar,’ Stone shook his head. ‘By the way, the girl didn’t die. I mean, she did die some years later in a traffic accident, but she didn’t die because of the abortion.’

‘Who was she?’

Stone lit his cigarette. ‘Some actress or other – starlet, I should say – she’d never had a part in a film or anything.’

‘Did Edgar meet her in Hollywood?’

Stone inhaled and blew smoke before replying. When he did, his voice was icy and almost menacing. For the first time I saw the dangerous quality that all actors must have if they are to be really good. This coilspring of repressed violence had seen many a bad film through reels of dull dialogue. ‘Don’t let’s pry into Edgar’s life,’ he said.

I turned the page of my notebook and decided to press on with the nuts and bolts. I said, ‘In a TV interview some years ago you said that a star should stop acting altogether rather than do character roles as he gets older. Do you still think that?’

‘A star has the vehicle built round him. He faces very different problems if he becomes part of building a film around another actor. Is that terribly vain?’ He gripped my arm tight enough to hurt. There was nothing homosexual about such Hollywood caresses; they were intended to get undivided attention, and Stone used them expertly.

‘No,’ I said.

‘If I was no longer playing leads – and luckily I’m having as many offers today as I ever had – but if I wasn’t getting leads, yes, I would stop acting.’

‘What would you do?’

‘Sail. I’d sail around the world, like Chichester or Knox-Johnson. A man only discovers himself when he’s alone with the elements.’

‘I didn’t know you were a sailor.’ I knew he had a motor-cruiser – that was mandatory equipment for all superstars; I’d seen it at Cannes during the festivals – but his enthusiasm for sailing was a new aspect of Marshall Stone.

‘I sailed alone across the Atlantic,’ he said indignantly. ‘I’m prouder of that than of any film I’ve made.’

‘Which route did you take?’

‘Shannon to Port of Spain, except that I got lost and had to swim ashore to ask where I was.’

‘And where were you?’

‘St Kitts.’

‘Not bad.’

‘Seven degrees error.’

‘When was this?’

‘Nineteen forty-six. A couple of years later I went to the States. It was forty-eight that Kagan Bookbinder gave me the part in Last Vaquero.’

‘I’ve never seen the voyage used in your publicity.’

‘It means too much to me, to have it used like that. You know what sort of biogs these publicity chaps dream up.’

‘They sent me yours this morning.’

He laughed. ‘Well, there you are.’

‘You won’t mind if I use the sailing story?’

‘I don’t know, Peter, it’s a very personal thing.’

‘So is a biography, Marshall.’

‘You’re right! OK, but use it soberly. I mean, don’t make it sound as though I’ve scaled Everest alone or something.’

Stone told Sam Parnell that looping would end for the day and one of Stone’s men helped him into his jacket, adjusted his handkerchief and held a comb and mirror for him. Stone nodded to tell me to go.

The biography could begin with the yacht. Far from the shipping routes a young actor, fresh from minor roles on the London stage, reviews his life so far.

The mountaineer, explorer and the lone sailor show a dogged indifference to hardship and privation. They also persevere in the face of a high probability of failure. These qualities they share with the actor. There were other things I liked about the lone yachtsman beginning: the sea and the stars, the nautical analogies and the man navigating through the dangerous shoals (of Hollywood?). Well, that might be too corny even for an actor’s biography.

I put away my notebook and thanked Marshall. His eyes were his most powerful asset, he could momentarily hypnotize a person he faced. He must have known this, for I suspect now that he held my hands in that vice-like grip of his only in order that I should not escape his gaze. For, at the moment when Stone took your hand, there was nothing in the world for him except you. A million volts of superstar surged through you and even the most hardened cynic could become a fluttering fan.

Most of the people working in the industry are fans. Not only directors, producers and actors, but the wardrobe workers, grips and sparks are all under the spell of the golden screen. Perhaps films would be better if more of the crew were the hard-nosed cynics that the audience have become, but they are not. At any première you will see the crews, dolled up in their best suits and sequined dresses, gawking at the celebrities as pop-eyed as school kids.

That was the way it was at the European première of Tigertrap. They all knew that it hadn’t impressed the Americans. The New York Press gave it a terrible roasting. Yet in Leicester Square the policemen were holding back the crowds as the Rolls-Royce cars arrived.