Читать книгу Close-Up - Len Deighton - Страница 7

Introduction

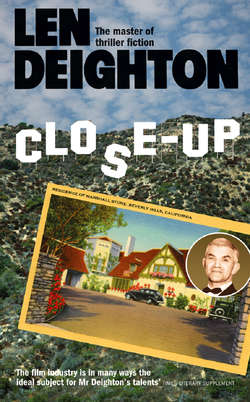

ОглавлениеThe story of Marshall Stone is the story of an actor. His dilemma is one that still faces many actors and actresses. Public television was born with the Berlin Olympics of 1936 and after a period of hibernation caused by World War Two, it soon became an affordable utility of the Western World, like hot water and electricity. But for actors and actresses television did not have the attraction offered by the theatre and films. Television became the residential home where reputations went to die and it has never escaped from this grim shadow.

Close-Up is the story of a writer and an actor. Actors, and sometimes writers too, are an exasperating breed; manic-depressives with a foot pressed hard on the accelerator or hard on the brake. Sadly, the film world does not treat these delicate temperaments with care and consideration. Few of us could withstand the sort of rollercoaster ride that leads to stardom and then back to earth again. Close-Up explains in detail the skills and hazards that the difficult art of acting involves. As you will no doubt detect, I like actors and actresses and all the other people who spend their lives making movies. I like them all so much that I had to write this book about them and about the convoluted way in which movies are made and devious movie deals put together. Writing several scripts – including two James Bond scripts – and producing two films, one of them a musical, gave me a wonderful insight into film, from the deal-making that starts the process to the editing and post-recording that ends it. This is how my education started.

‘Maybe you suddenly hate the way he parts his hair.’ This was Harry Saltzman’s way of describing the irrational personal showbiz dislikes that are impossible to account for in any other way. Harry felt that formal written contracts were only valuable when the parties concerned forgot the promises they had made at the start of the deal. He was right and I never needed to refer back to any contract I had with him. I was very fond of Harry Saltzman, who had co-produced the James Bond films and by buying the film rights for The Ipcress File in 1961 started both me and Michael Caine on our respective careers. But Harry was a very private person and it was a sad fact that he never seemed to distinguish between his friends and his enemies.

I had dinner with him one evening and picked up the bill. Harry was quite alarmed. ‘I always pay the bills,’ he said. He was resigned to being exploited. He never showed resentment about the freeloaders who drifted to his lovely Mayfair mews home in the early evening with a view to joining him, his wife and anyone he was doing business with, for a lavish meal in some fine restaurant.

I owe a great deal to Harry Saltzman. Writers are not respected in the movie business. Along with directors and all the other technicians they are despised and regarded as easily replaced workers with limited skills. But that was not Harry’s way with writers; he liked them, even if he did routinely shuffle his pack of scriptwriters, so that most of his films went through several total rewrites before shooting began. The first lesson I learned from Harry is that films are created by producers: they buy the story and choose everyone else who makes it into a film. I started to think that becoming a movie producer who wrote his own material would be unceasing fun. In this assumption I was proved wrong.

Without Harry’s kindness I could never have written this book, Close-Up. I questioned him relentlessly about films, filming and his career. He immediately responded to my thirst for knowledge by assigning me to write a screenplay for From Russia With Love and including me in the half-dozen people who went to Turkey on the recce trip for the film. On a separate occasion, Harry invited me to meet him in Paris so that we could watch a remarkable James Bond sequence in which a jet-propelled backpack sent Sean Connery’s stunt double up to rooftop heights. By the time my book, The Ipcress File, was being filmed in a wonderful old house in Grosvenor Gardens near Victoria Station in London, I was beginning to understand something of the way movie producers transform books into movies.

Harry became a mentor to me. So when I was working on the final draft of a screenplay based on Joan Littlewood’s stage show, Oh What A Lovely War!, I went to Harry to ask his advice and seek his approval. He was occupying a tiny circular office in a turret surmounting one of Shaftesbury Avenue’s famous theatres. As usual, Harry was wearing a superbly tailored suit, crisp shirt and silk tie with the bright red socks providing the only hint of eccentricity. He was his usual congenial self. He warned me that Joan Littlewood’s stage production had closed many years previously and that numerous people had tried to make it into a film. ‘None of them got a deal,’ said Harry. ‘So don’t put down any of your own cash.’

It was too late. I had already paid Joan, out of my own pocket, for a six-month option on the screen rights. I was disconcerted by Harry’s warning and spent a few nights worrying that I had taken too much for granted. With diminishing money to pay for all the costs that come with pre-production, and with only a bundle of carefully typed pages of film script, and some rough sketches and photos of chosen locations such as Brighton Pier, to show for months of hard work, I was nervous. But Fate often smiles upon the unwary and events took a sudden turn for the better when I was invited to have coffee with Eva Renzi, a German actress who was in London to star in Harry’s film of my book, Funeral in Berlin. She had been having lunch at the Dorchester Hotel with her agent from the William Morris Agency. At that time the Dorchester was the world’s most important gathering spot for film people. By the time we were drinking our third or fourth espresso, the William Morris Agency was representing me as a film producer.

All films need an early financial commitment and John Mather, the head of the London office of William Morris, took my script and my location photos to Paramount where Charlie Bluhdorn reigned. Fortunately for my film project, Charlie, a tycoon who had recently added Paramount to his array of business ventures, was a dedicated anglophile. I became fond of Charlie; he had an entertaining line in self-mockery and endless anecdotes about his beginnings searching through scrap yards for engine parts. I suppose my years researching books has had a lasting effect upon my social life for, despite Charlie’s reputation as a fire-eater, I encouraged his reminiscences and we became friends.

It was about this time when I took a call on my car phone that was to face me with a difficult decision. The year before, in Paris, I had become friendly with Lloyd Chandler, a Canadian uranium prospector who had ‘struck it rich’ as they say in movies. He donated large sums to a fund organized by the celebrated philosopher Bertrand Russell, and became such a friend of Russell that he was consulted about the legal implications of a letter the great man had written to a publisher many years before. It concerned the autobiography that Russell was completing. Lloyd said his friend Len Deighton knew all about literary contracts and publishers. In fact I know little about such things but an offer to spend some time with Bertrand Russell – widely regarded as the world’s foremost intellectual – was not something to be declined.

Together with my wife, Ysabele, I went to see him. My time in Plas Penrhyn, Russell’s home in Wales, was a delightful experience. ‘Bertie’, as he was called by those around him, was over ninety years old but he was as sharp and witty as anyone I knew and he enjoyed arguing. So it set our relationship on a firm basis when I found his one-sided view of the Vietnam War unconvincing. And I told him that without an agreed fee his letter had no legal importance. But to be on the safe side I suggested that Bertie consult my old friend and adviser, Anton Felton. He confirmed my verdict on the letter and eventually assembled and collated Russell’s archive and became his legal executor. It was during our time at Plas Penrhyn that Bertie told me that the Beatles had been speaking to him about making an anti-war film and that Paul McCartney wanted to talk to me about it. That, he said, was the prime reason for his invitation. A few days later, in our south London home, my wife and I cooked Paul an elaborate Indian meal and spent the evening discussing his project. But the Beatles wanted an anti-Vietnam war film with an up to date setting. I would have enjoyed working with Paul but I could see no way to become a useful part of the Beatles project. I was deeply committed to two films by that time, and Paul and the Beatles were in a hurry.

To run Paramount’s European operations, Charlie Bluhdorn had appointed George ‘Bud’ Ornstein. Bud knew more about old Hollywood than anyone else I ever met. He was related to the legendary Mary Pickford and the stories he told about the days she ruled the movie world enthralled me and provided a basis for some of the material used in Close-Up. Bud was responsible for many of the fine European films of the fifties and sixties. Luckily for me, as well as being a major figure in the film world, Bud was a pilot and an aviation enthusiast. My hours with him were always a delight. It was Bud who first pointed out that, since my script for Oh! What A Lovely War proposed many scenes on Brighton pier and was largely dependent on outdoor locations, it would be wise to defer shooting until the following summer. It was good advice and yet by this time I had rather grand offices – once occupied by Alexander Korda – overlooking the traffic swirling around Hyde Park Corner (the site is now a hotel). The continuing expenses during such a gap in the schedule were going to drain from me money I couldn’t afford.

To fit into the empty time I produced another film. I assigned the screen rights of Only When I Larf, my recently completed book about confidence tricksters, to my production company, and had a writer friend of mine – John Salmon – write a screenplay. By chance, the story was set in New York City, London and sunny Beirut, Lebanon, and to dodge the winter weather I scheduled the production for all three locations. I engaged Basil Dearden to direct and David Hemmings to star. It was while I was casting Only When I Larf that Richard Attenborough called me out of the blue and asked if he could direct my film of Oh! What a Lovely War. I had never met him. He had obtained a copy of my screenplay from his friend, John Mills, to whom I had tentatively offered the role of the infamous General Haig. Dicky Attenborough had never directed a film but he had decided that the time had come for him to do something other than acting. I wasn’t sure he was the right person for me; this was a large-scale musical with all the added complications that would bring. Dicky had spent most of his adult life acting in movies and knew a great deal about the way they were made, but directing a full-colour musical with dancing and outdoor locations would be a challenge. He had also seen the script for Only When I Larf and suggested that he could play the elder man against the young man played by David Hemmings. This would give him a chance to spend time with me during the filming and give me a chance to make up my mind about him. William Morris, who represented me for this movie too, proposed David Niven as the co-star and Basil Dearden was against using Dicky, saying he wanted someone more ‘sexy’. I nevertheless cast Richard Attenborough as the elder confidence trickster. It was virtually the last role of his long and distinguished acting career.

Despite the logistics and expense of filming in Beirut and Manhattan my production of Only When I Larf went smoothly. It was not easy for Basil Dearden; although he had directed dozens of studio films he had never worked on an all-location one. He also had to put up with my choice of a very young lighting cameraman and such innovations as overhead lighting that permitted 360-degree camera pans and my insistence upon mixing daylight and artificial light without corrective coloured ‘gel’ screens. On the whole it proved a lucky production. The only major hitch was the noise of our big mobile generator which, parked on a street in Beirut, spoiled some of the recording. This demanded the added time and expense of some post-synched dialogue but Basil was a professional and we squeezed the budget to pay for it. I followed the film through the editing and entire post-production and decided that films could be made or crippled by these last weeks of work.

By this time, I was talking to all manner of people who wanted to be a part of the Oh! What A Lovely War film. I had half a dozen directors asking for the job – Basil Dearden had mentioned it almost every day on the set – and I even had offers from some of the Hollywood greats, including Gene Kelly. In any other circumstances, I would have given anything to work with Gene Kelly but this film dealt with an important chapter in Britain’s history and it had to have a British director. My screenplay brought many drastic changes to the stage version. The one-act-after-another ‘music-hall’ format of the stage show would not make a movie. There was no ‘story’ in it. For a film the words and songs had to be incorporated into written narrative; a story of the war that year by year reflected the nation’s mounting gloom and sadness. Individuals were combined to become the Smith family, whose men volunteered gladly to serve in the war that killed them. And most important of all, I had envisaged a powerful ending; a vast expanding landscape of graves accompanied by the wonderful old Jerome Kern song ‘They Didn’t Believe Me’. My script met the major challenges, which is why Bud Ornstein at Paramount had supported the project.

Like most screenplay writers, I had visualized each and every shot and kept an eye on the probable costs of each location and its whereabouts. Dicky Attenborough understood that it was going to be restricting to have a producer who had written the screenplay looking over his shoulder throughout the filming but after sitting around with me on the Only When I Larf locations, and listening to me explain my screenplay shot by shot, he promised to keep to every word of it, and welcomed having a storyboard artist to sketch proposals for each day’s camera set-ups. The daily storyboards were the work of Pat Tilley, a gifted artist who had been a close friend of mine since our days as illustrators. Bud Ornstein still had doubts about trusting such a big musical film to Dicky Attenborough, a first time director, and no doubt eyed me in the same way, but Charlie, who was an instinctive gambler, said we should take a chance and pointed out that if the worst came to the worst we could switch to another director at any time. I had already decided that Dicky had the energy and ambition that would be so important, and said so. At an evening meeting with Charlie and Bud in the Belgravia home of my agent, John Mather, a handshake deal was done. As I had promised everyone, Dicky stuck to my script and the weather was kind to us. For Dicky it was the beginning of a long and illustrious directing career and I am flattered that Oh! What A Lovely War is clearly his proudest achievement and the film with which his name is principally associated.

My years in film production were not a time of unalloyed joy but it provided challenges and delights in abundance. The crews and actors with whom I worked were talented and hard-working and did everything to help me. There was a lesson to learn every minute. For anyone who wants to know exactly how a movie is made there is no better way than to sign each and every cheque, with someone standing by to answer questions about the money’s destination. For most of my lessons, I gladly give credit to Mack Davidson, a wartime Spitfire pilot who, as my Executive Producer, guided and advised me constantly and became a close friend. Mack’s contribution to the making of both films was enormous. Mack died on the final day of shooting Oh! What a Lovely War. There had been no sign of illness and I was devastated. We had planned to make another film together and he had become like a wise and experienced elder brother to me.

Technology made the movie of Oh! What a Lovely War more complex than the stage show, which had the dashing exuberance that Joan Littlewood gave to everything she touched. My film would have no blood and no fighting, and death came as a bright red Flanders poppy. Brighton Pier – a glittering attraction – became the War, and from a constantly expanding booth General Haig sold tickets for it. Some film executives proclaimed such symbolism too subtle and for some perhaps it was. It was the skill and experience of Mack Davidson that gave me the confidence and encouragement that I needed to bring my unconventional movie ideas to fruition. Many other supporters deserve credits. I had a talented and indefatigable casting-director in Miriam Brickman. Casting was of course a vital ingredient and I was probably the first producer to use video equipment to cast most of the roles. This gave the actors the freedom to come to the Piccadilly office at any time convenient to them, and it gave me the chance to run, and rerun, the tapes as and when I had time, and to discuss the choices with Dicky Attenborough.

A crucial decision in the making of any musical entertainment is how to handle the transition from speech to song. In Joan’s delightfully old-fashioned act-by-act music-hall style, the abrupt insertion of songs was expected and welcomed. But musical films demand a smooth transition into music and song. Operas had used recitative for centuries and in the nineteen-thirties Rodgers and Hart, working in Hollywood, invented a simple device of rhymed conversation with musical background that easily moved into their songs. I couldn’t use this rhyming method because the entire dialogue for Joan’s Oh What A Lovely War! had actually been spoken during that war. I had added dialogue for scenes that were not in the stage version but I had kept to that restriction and used only words from the past. Joan introduced me to AJP Taylor, the eminent historian who had advised her, and he became an adviser to me and eventually a close friend. Getting everything right was a headache but it was an absorbing task. Perhaps my transitions were not perfectly smooth but they worked adequately.

The body movements of the actors and actresses – not just the dancers – were important to me and I brought in Eleanor Fazan, experienced choreographer, to oversee the whole production and to ensure that such devices as the leap-frogging officers could be smoothly integrated into the outdoor location. Together with Eleanor I checked out every dancer to make sure they looked right for the wartime period. I wanted the costumes to be authentic and to conform to the changes that the progress of the war brought. I found Tony Mendleson, a distinguished and experienced costume designer, and he gallantly accepted as a historical adviser May Routh, an art school friend of mine who later became a successful costume designer in Hollywood. Her knowledge of military and civil uniforms and experience as a fashion artist made a vital contribution to the film. The sketchbook she compiled during her research and the filming is a most lovely record and deserves to be published in volume form. To have the slings, medical dressings and bandages right I employed a Red Cross nurse to check such things prior to each shooting sequence. I had many sets built on the pier and I visited suggested locations well before schedule, so that I could switch to alternatives if needed.

There were still some surprises to come. I didn’t fully appreciate the fact that movie credits can be a battlefield where determined Darwinians fought to enhance their reputation at the expense of others. I even had people asking me for a co-writing credit on my script. I had commissioned Ray Hawkey, with whom I had studied at the Royal College of Art, to design the titles. They were original and beautiful and now in a childish attempt to shame the wannabes, I told Ray to remove my name from the credits. But I had severely misjudged the clamorous ones. The removal of my name only encouraged the claimants.

Credit or no credit, the production company was entirely mine and the producer is the only person who can’t be fired or even replaced. So in accordance with my contract with Paramount, I continued to nurse my film through the postproduction weeks and deliver it. I had learned a great deal from the previous film. No claimants were around now; postproduction is a lonely time, far removed from the glamour of lights and cameras. I watched and learned more every day as Kevin Connor, the film editor, cut it into shape and the complex sound track was trimmed and modified and a thousand small changes were supervised by truly dedicated technicians. By the time I had a final cut of the film I knew that these amazing things I had seen must not be wasted. I decided to write a book about the film business showing its joys and technicalities plus a few of its warts and wrinkles. Close-Up is not reality; writers go beyond reality to find and depict truth. Close-Up is the truth as I experienced it. A year or two later, one of the proudest moments of my life came as I stood at the bar of Les Ambassadeurs Club off Park Lane. Bud Ornstein said to me: ‘I was reading one of your books recently and I thought this is someone who really knows about airplanes. Then I read Close-Up and thought this is someone who really knows about the movie business. Then I realized that you had written both of them.’

I hope you will share Bud’s satisfaction. If not, you can try one of my aviation stories, my history books or one of my spy stories. All that remains to be said about Close-Up is that although it reflects what I learned producing two films it is in no way an account of that experience or a memoir. The twists and turns, vendettas, deals, disappointments and betrayals are not specific ones and none of my characters depicts real people living or dead. But these fictional people are real to me.

When, years later, in a rather mangled version, a DVD was made of Oh! What A Lovely War I was not invited to contribute an interview. Marshall Stone would have understood.

Len Deighton, 2011