Читать книгу Only When I Larf - Len Deighton - Страница 7

Introduction

ОглавлениеThe ideas in this story were planted many years before I began writing it and its format endured many radical changes. After completing my military service as an RAF photographer I won a grant to study illustration and graphic design at St Martin’s School of Art in Charing Cross Road, London, where I had studied briefly before my RAF service. To supplement my ex-service grant I took photographs for my fellow students and for the staff too. It was in the early nineteen fifties and photography was not the universal accomplishment that has come with fully automatic cameras and digital technology. Although it was a hand to mouth existence I scraped up enough money to rent one room in Soho and became a resident of that lively district of central London. Foreigners abounded: Mozart lived in Frith Street, Canaletto in Beak Street and Karl Marx in Dean Street, just around the corner.

At 10 Moor Street I rented the tiny back room at the top. The ground floor was occupied by a man’s shop that specialized in American-style clothes, e.g. wide-brimmed fedoras, brightly coloured ties and Bogart-style trench coats. It was about as near to St Martin’s School of Art as it was possible to live and it was cheap. With a chair that unfolded to become a bed, I used it as a stopover during the week and visited my parents at weekends. There was always a warm welcome and my mother was an outstanding cook who did a lot of my laundry, too. Life would have been hard without those two wonderful parents. It was the nineteen fifties and no one had any money; at least no one I knew had any money. The other top floor tenant with me in Moor Street was an estate agent, an elderly man – named Long, as I remember – in partnership with his daughter. They were very friendly to me and were tolerant in respect of the endless stream of noisy art students and other Soho acquaintances that came clattering up and down the stairs; and they never betrayed the fact that I was sleeping in my office.

Living in Moor Street extended my education. Soho in the fifties was a place where gangsters did little to hide their profession, neither did the prostitutes. Plump and contented policemen, especially those of the vice squad, were equally evident. Directly opposite my digs – on the corner of Greek Street and Old Compton Street – there was a large empty bomb-site where a polite and pleasant man called Nigel worked from a van serving coffee and sandwiches all through the night. There was always a small crowd there; it was Soho’s nocturnal Athenaeum. Arriving back late one night I was distressed to find I had forgotten my keys. I went across the street and very quietly asked Nigel if he knew anyone who could help me. There was no problem. On Nigel’s introduction, an elderly man put down his coffee, came across the street, put on his spectacles and noiselessly opened both street door and my office door with some small unseen implement. He refused payment and was back drinking his coffee before it cooled. ‘Always ask for a ‘builder,’ Nigel advised me afterwards. Euphemisms abounded in Soho at that time.

It was one of Nigel’s customers who introduced me to a ‘press agency’; a large room on the first floor of a building in Newport Street, round the corner from Leicester Square tube station. The occupant there was a Fleet Street veteran named Gilbert who recycled press handouts that arrived by post every morning. Most of them came from Embassies – Argentina sent bundles of them – plus commercial press releases and invitations to wine and cheese gatherings, which Gilbert always kept for himself. What Gilbert did with the rest of his mail I never discovered but his income was amplified by a pool of regular visitors who for a small fee had their mail sent to his address. I must not say that all of them were confidence tricksters; I think some were errant husbands or debt-plagued fugitives. Whatever they were they proved for the most part entertaining company and I spent many happy hours (when I should have been studying at St Martin’s) in this room nursing a mug of Nescafé and waiting for the islands of dried milk to dissolve. (Brewing tea was too complicated and alcohol verboten by Gilbert.) My entry fee was a regular supply of biscuits; chocolate-covered oatmeal ones were by far the favourite. In those days, tailor-made suits were almost as cheap as ready-made ones and these men favoured dark suits with white shirts and sober ties. Although their anecdotes were guarded and circumspect I soon decoded their stories and learned the mechanics of some of their shady transactions. I also recognized that the rationale behind their operations was that the people tricked were greedy and deserved their losses. It was greed that lured ‘marks’ into their loss, they said. I suppose they were mostly ex-servicemen restless and uneasy in that topsy-turvy post-war world but to my young eyes they seemed calm and confident, their scepticism arming them against any adversity. It was lucky that I was accepted by them but I think they mistakenly believed me to be connected to Gilbert by kinship or employment. I did not discourage this impression.

Some years later when I was writing books for a living, I remembered the men in Newport Street and decided to write a non-fiction book about confidence tricks large and small. I put a classified advert into the Daily Telegraph asking any reader who had experience of confidence tricks or tricksters to contact me at a box number. The response was almost overwhelming. I received so many letters that I had to employ a friend to help me sort and classify them. And I found tricks and swindles of remarkable size and international scope. These people were a far cry from the petty-cash crooks I had met in Newport Street. I took some of the most promising correspondents to lengthy, entertaining lunches and made notes of some of the most amazing and exciting escapades. Names, dates and all necessary references went into my notebook. It was astonishing raw material but writing it as a non-fiction work would be an expedition into that dangerous no-man’s land that divides scandal from libel.

No professional writer ever throws researched material away, so this went into box files and was put on the top shelf to gather dust as I worked hard to fulfil promises and contracts. It might have remained forgotten except for a chance meeting in the Porte de Clignancourt flea market in Paris. I was there researching An Expensive Place to Die, a book about the decadent Paris underworld. It was a long task and without the unstinting help of a detective of the police judiciaire I might never have got started. He served in the brigade mondaine which is the quaint title the French give to their ‘vice squad’. My guide knew everything and everyone; people high and low, people in bars, exclusive clubs and brothels greeted him like an old friend. He showed me the flea markets where stolen goods sometimes came to light. Central Paris was his beat and without his help and guidance An Expensive Place to Die would have been a different book – but that is another story.

I love flea markets, and only locals are to be found at the Clignancourt flea market on Monday, the third and final market day, when unsold items are likely to be marked down. It is especially empty when that Monday is cold and wet. ‘I know you. From Newport Street. Remember?’ Yes, I remembered him, a tall thin pipe-smoker who never let his fine leather document case far from his side. No document case today and no pipe either. His face had reddened since those long-ago days and he had grown a square-ended moustache. He was wearing a tightly fitting cloth cap and one of those short camel-coloured ‘British warm’ overcoats. His appearance suggested an officer of some smart British regiment. I wondered if this was a contrived appearance connected in some way to his precarious profession. But many expatriate Englishmen tend to parody national characteristics and that may have been the case with him. The darkening sky and the bleak expanse of the rain-swept flea market weighed against the chance to talk to a fellow countryman who might share a memory or two; it tempted him to suggest that I join him for a drink.

‘You disappeared,’ he said accusingly as we sat drying off in an otherwise empty café on the Avenue Michelet. We had black coffees and, at my suggestion, small measures of Framboise, a type of Eau de Vie to which I had become dangerously fond during my stay in Paris.

‘I moved home,’ I said. My ‘disappearance’ from the St Martin’s area was due to a scholarship at the Royal College of Art in South Kensington. But since I had never revealed to the men in Newport Street that I was a student, I saw no reason to discuss that now.

‘You didn’t miss much,’ he said. ‘Gilbert’s lease ended soon after Benny went to prison, and there were no more of those mail-order get-togethers.’

‘Benny went to prison?’ I remembered Benny; a middle-aged chain-smoker with a gold lighter, gold signet ring and gold pocket watch complete with chain. Despite his hard face and cold eyes it was always Benny who greeted everyone with a smile and told jokes that required funny accents. It was Benny who always poured me a cup of coffee in those early days when I felt socially excluded from this exclusive gathering.

‘It was the girl,’ he said. I must have looked puzzled. I never saw a woman in that room in all the many hours I spent there. ‘She collected him in a car; a grey Sunbeam Talbot convertible; a lovely little car. That’s why he was always looking out of the window when it got near the time.’

He finished his Framboise and got to his feet. ‘My turn,’ I said, and signalled for two more drinks to delay his departure. He sat down. I didn’t press him for more information but when the drinks came he completed the story. ‘She was only a kid but with all that make-up she looked like a woman of twenty, or more. Benny was mad about her. They took off together for some place where Benny had grown up; Nottingham or somewhere like that. The funny thing was that Benny didn’t even suspect that it might be her father’s car and that she didn’t have a driving licence, insurance or anything. I suppose she was mad about him too, in that silly way you see in young girls. Goodness knows what yarns Benny had spun her.’

‘How did they get caught?’ I asked. Soho during that post-war period was a haven for deserters of all nationalities and furtive men selling booze, drugs and the glittering prizes of ‘war souvenirs’ such as Luger and Beretta pistols (the latter passed on quickly as each buyer discovered they wouldn’t take standard 9mm rounds). Lasting relationships were few and far between and drinking companions were apt to disappear without saying goodbye. I would have thought Benny a master of the art of eluding pursuit.

‘Benny used that post office opposite Leicester Square underground station as a poste restante address for his little game. He knew his postal orders would be piling up there and eventually he became so short of money that they drove back to London to collect them. In those days you could park in the street there and Benny sent the girl in to collect his mail. She had the necessary authority to do it but the clerk said the poste restante mail was in some locked back room and would take ten minutes. Of course he was on the blower to the law. Benny waited and waited. If he had driven away he might have disappeared all over again but he was crazy about her as only a forty-year-old playboy could be.’ He laughed without putting much effort into it. ‘Benny climbed out of the car and went into the post office just as a couple of plain clothes coppers arrived there. She was only a kid. Her father was kicking up a dust. They hammered him; stealing a car, abducting a minor as well as his postal order capers. I don’t have to list it all, do I?’ He smiled.

‘Poor Benny,’ I said. It is no fun to play a tragic role in a farce.

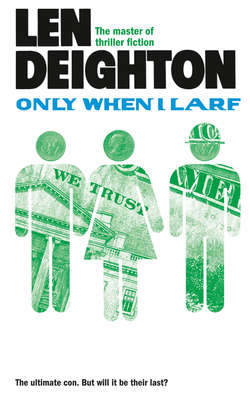

I shuddered and didn’t ask what the sentence was. And with that heartless reaction that cripples the humanity of every writer, I began fashioning it into a chapter of a book. But by the time I started writing Only When I Larf Benny and the others had faded from my memory. My confidence tricksters were the smooth sort of rogues that answered my advertisement, and in my book I used some of their more elaborate swindles. Making it fiction removed the problems. When I became a film producer Only When I Larf was the first film I made.

But before I started writing there were decisions to be made. Was this going to be the first-person story of a rich and flashy Benny or someone like him? Certainly not. The real money was made by teams, well-financed teams. That was the lesson I had learned during my lunchtime research.

Creating your narrator for a first-person story demands much thought. Somerset Maugham mastered the idea of a narrator who is the undisguised voice of the author but this creates an extra barrier between writer and reader. I believe a first-person story should have an admirable and heroic hero who is also fallible and imperfect. The central character must be created so that the reader sees through the explanations and excuses to recognize all the hero’s faults and frailties but loves him nevertheless. This is how I designed Bernard Samson, and in nine books had him develop and change under the relentless scrutiny of the reader. In Violent Ward Mickey Murphy is a man both larger than life and yet a reflection of the life around him. In Close-Up a first-person narrative by a film star’s biographer is threaded between a third-person story of the star. The creation of the narrator is the essence of a first-person story. I am not experimental by nature. Books, plays, films or poems described as ‘experimental’ do not attract me. But the three-person team depicted in Only When I Larf seemed to cry out for a first-person narrative from each of them. It is said that all novels should express both a feminine and masculine vision of the world and I have always believed that. After lengthy consideration this was the format I chose. It was quite demanding and I hope you feel the hard work it represented was worthwhile.

Len Deighton, 2011