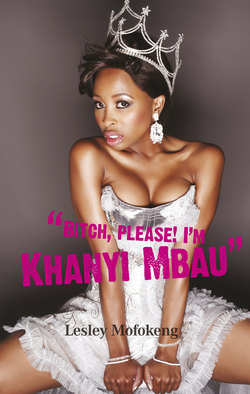

Читать книгу Bitch, please! I'm Khanyi Mbau - Lesley Mofokeng - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1. The Queen of England

ОглавлениеWe are being chauffeur-driven in a roaring 1960s Rolls Royce Phantom to the 2011 South African Music Awards (SAMAs) at Montecasino, north of Johannesburg. A car fit for stars like Elizabeth Taylor and Aretha Franklin. Kate Middleton, the Duchess of Cambridge, had arrived in one for her wedding at Westminster Abbey a few days earlier. But the Phantom doesn’t impress Khanyi at all. I’m in front and she and her sister Thandeka are curled up in the back on the newly upholstered leather. She would have much preferred something flashier like a Bentley and makes a face as we slow down over the speed bumps to preserve the classic car with its creaky wheels.

Khanyi looks tomboyish and a bit like Charlie Chaplin in a tux and bow tie. It’s a bold look fashion bloggers celebrate for its daring and originality. Very Khanyi. She asks our driver what champagne has been arranged for the short trip from Sandton to Fourways.

“JC Le Roux,” he says.

You could have heard a pin drop. Khanyi gives him a look that would melt steel. The temperature has plummeted in here.

“And you think it all goes together? A Rolls Royce and the Sandton address? Did you check the address before you collected JC?”

He doesn’t answer.

Her blue contact lenses seem to burn with rage. The driver says something about the JC already being packed. Luckily for him the notoriously busy Rivonia Road is clear for once and we zoom past the traffic lights. Through the window the setting Highveld sun has a glorious orange glow. We’ll make it. Then Khanyi shrieks. She’s forgotten her phone at home. She can’t demand a U-turn because we’re already late. I give her my phone so she can assure her music collaborator and Kalawa Jazmee mogul, DJ Oskido, that we are on our way. Fine. Done. Then she shrieks again. Everything is out loud with Khanyi. A big song and dance. She is a natural-born attention-seeker. The R80 000 Kate Middleton replica engagement ring that Browns Jewellers gave her for the SAMAs is absent from a newly manicured finger.

“This was its debut,” she whines.

Then remembers it’s where she left it at home, along with her phone. Khanyi forgot to put it on. The mood in the Phantom has soured. We don’t touch the champagne.

Out in the dusk, the crowd chants: Khaanyee . . . Khaanyee . . . Khaanyee . . .! They ignore the celebs unfortunate enough to arrive at the same time. Khanyi looks immaculate in the rippling flashes of popping cameras. This is her home. She drinks in the adoration and it seems to make her younger. Smooths her skin, deepens her glow and crowns her as someone special. It’s amazing to see her transform from the sourpuss in the Phantom to this poised, glamorous star. She has many selves she can flip through and put on to fit the occasion. She is her own best accessory.

Khanyi is ushered in and instantly abandons me. I’m left to secure the VIP tags that’ll let me sit next to her at her table. I rush up and down Montecasino from one event organiser to the next but none of them have my tickets or VIP tags. A lowly entertainment journo like me has been left dangling in the wind. Luckily DJ Oskido passes by and I lay my plight on him. He has a spare “artist” tag that’ll get me in. I’m finally seated behind the band with an unobstructed view of their behinds.

Later Khanyi has swapped the tux for a security guard uniform, topped off with a becoming beret, to perform with kwaito star Professor, who, with multiple well-deserved awards, turns out to be the night’s big winner. Seeing Khanyi up there drives the crowd in the dome insane. Her face is multiplied on giant screens around the venue as she works it onstage to Ijimaphi and Jezebel. This is the highlight of the night by far. Khanyi owns the dome. She feels bigger than ever in that moment. A genuine star.

The change of costume is symbolic. From tux to security guard, upper to lower class. The dichotomy is in her. Contributing parts of her personality, her drive, her approach to the world. She is someone who sips Mumm Champagne yet is happy wolfing down a kota (a small bunny chow) on a street corner. She contains multitudes of personalities, as anyone who symbolises a nation’s secret hopes and dreams must. A shameless celebrity who dates rich old men and destroys marriages on her way to the good life on the one hand, and on the other a darling of the crowds, who see her as an avatar of a better life.

She resonates with people who want to better themselves. With anyone who wants to be someone. She is a real star and a lucky girl from ekasi (the township) who’s done good. She’s just like us, but more motivated somehow, more maniacally driven to be someone.

Khanyi was born at Florence Nightingale Hospital in Hillbrow in Johannesburg on the evening of 15 October 1985. Her mother, Lynette Sisi Mbau, was a 25-year-old corporate climber working in the finance department of the pension fund at Barclays Bank. She insisted on a private hospital rather than a crowded public one in Soweto. It was a gesture that would define her daughter’s life – always the more expensive option. The urge to be exceptional.

Khanyi’s father, Menzi Mcunu, was not in the delivery room. They weren’t married and no lobola had been paid. The young couple were only dating. Mcunu had no claim to the child but he named her nevertheless: Khanyisile, one who brings light. The baby kept her mother’s surname. It made her different right away. Lynette soon left baby Khanyi with her parents in Mofolo, Soweto, and returned to work.

Gladys Felicity Mbazane-Mbau, Khanyi’s granny, would virtually raise her. She was a remarkable woman, very capable, and respected by the community as a specialist midwife at the Rand Mutual Clinic in the city. She was to be Khanyi’s rock. The source of her self-esteem and the uncomplicated support she needed through the bad times.

Even her genealogy is exceptional. Khanyi is undoubtedly the most famous person of Fijian origin in South Africa. The Mbaus can be traced back to the South Pacific Melanasian island nation of Fiji. Her ancestors were possibly missionaries who came to South Africa and ultimately mixed with the locals. Other versions of the family history involve slaves from the east who worked for the Dutch East India Company, much like the Cape Malays, during the time of Jan van Riebeeck.

Her talented grandfather, Babes Mbau, played alongside Hugh Masekela in the Sophiatown days of the 1950s. He was a fine musician and delighted his granddaughter with yarns from that romantic era. Tales of bands like the Manhattan Brothers, The Woodpeckers and The Skylarks, and unforgettable songbirds like Dolly Rathebe, Miriam Makeba, Dorothy Masuka and Thandie Klaasen. He talked about the camaraderie of community halls and the spirit of resistance in the streets. It was before the apartheid government tore down “Sof’town”, the terrible destruction of a black Bohemian enclave, and forced everyone to go to Dobsonville and Meadowlands in Soweto. Adding insult to injury, they turned it into a whites-only suburb called Triomf (Triumph). It was the most creative time in Babes’ life. Bright-eyed Khanyi listened to these stories at the old man’s feet and she has a real feeling for jazz to this day.

Her first awareness of romance was the story of her grandparents’ love. They met one evening in Sophiatown. Gladys was a deft ballroom dancer, full of poise and grace, with a swan-like neck. She danced in a troupe alongside a young Felicia Mabuza-Suttle, the talk show host. Dashing Babes was infamous for breaking hearts and playing the field. It wasn’t exactly love at first sight.

“I didn’t think he was my type,” Gladys told little Khanyi.

She kept Babes at bay until one night at a dance when he got up on the stage, quite drunk, and said into the microphone: “Gladys Mavuso, you are going to marry me!” Her friends erupted around her, cheering him on, but Gladys couldn’t believe his nerve. How dare he propose like that? But she eventually softened to him, liked his daring, and realised he meant it.

MaMavuso, Khanyi’s maternal great-grandmother, was another formidable woman. She owned horses and had a business selling cold drinks and magwinya (fat cakes or vetkoek). The Mbaus were generally seen as a cultured family of higher standing than the average Sophiatown local. Trevor Huddleston, the renowned cleric and anti-apartheid activist, even tutored MaMavuso, and remained a life-long friend. Babes was from a poor background and was the quintessential struggling artist. It was noble poverty. When MaMavuso died, he was there for Gladys and that brought them together in a 40-year marriage.

Khanyi was their first grandchild and they spoiled her. She got everything her heart desired. They were both very Western in the way they dressed and saw the world. They both spoke fluent English. Gladys insisted one should “speak English well or don’t bother at all”. Dressing and behaving properly were in the rules. You always had to dress appropriately and speak correctly.

Gladys would cane you if you broke the rules. She ran her household with the decorum and attention to detail of Buckingham Palace. Khanyi lovingly called her gran the “Queen of England”. Everything had to be just so. She was strict but caring. Good cop and bad cop in one.

Babes turned out to be a canny entrepreneur. He managed to run a printing company during the apartheid years. All his life he insisted that the children learn a musical instrument. Playing music had meant so much to him, he wanted to pass that joy on but warned it was impossible to make a living as a musician. Khanyi’s aunt ensured her upbringing was even more cosmopolitan and unusual. Nikiwe lived and worked in Germany as an engineer for BASF. She was a smart, successful woman who had travelled and seen the world, and her visits left the little girl with an expanded sense of her own potential. There was far more to see and do than the township offered.

As a girl, Khanyi loved cartoons and eating bowls of cereal in bed. Significantly, she was addicted to The Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous, an early reality show that celebrated the excesses of the 1980s, showcasing giant homes, expensive cars and yachts. Can there be any doubt this planted an envious thought in her young brain? Something along the lines of “if they can have all that, why can’t I”?

She also liked CNN and never missed the evening news on TV1. She would hop onto Babes’ lap in his rocking chair and they would take in the bulletin together. The images of a rapidly changing country. Babes taught Khanyi to count in that rocking chair and he also taught her how to play the piano. But her mind wandered during the lessons. She was far more interested in colouring in.

Gladys tried to inject some grace and poise into the child by taking her to ballet classes. All that demanding effort and discipline would turn her granddaughter, she hoped, into a little black swan. Like Gladys, Khanyi would dance professionally later in life.

“I was brought up believing the Mbaus were regal,” Khanyi says. “They speak well and are to be envied.”

She would tell her grandmother she was going to be rich and have a big house. That she would have orphanages and children’s hospitals named after her. She was affected by the images of malnourished children in Ethiopia that were all over the media in the 1980s. “It broke my heart,” Khanyi says. “I told my grandmother that my business would be called Mbau Bridges. I wanted to help. I was groomed to speak properly and make sense. Inculcated with the belief that I have to be the best I can, a leader or the boss – be the owner and founder of things.”

That self-belief was challenged by an absence in her life. Khanyi longed for her father. “I had wonderful grandparents,” she says. “I had my mother, my aunts and uncles but I had no daddy. When we did school projects and I had to draw my family tree, I had to put my grandfather in the father block.”

Babes didn’t approve of her father. Menzi Mcunu was just a lowly taxi driver to Khanyi’s grandmother. He didn’t visit much and young Khanyi had very little information about him. That her father was Zulu and lived in Zondi, a suburb of Soweto, in a four-roomed house was about all she knew about him.

“He spoke funny,” she recalls. “But he fascinated me. I spoke to him in English and he tried to converse in his broken English. I’d never seen someone like him. He wore dirty overalls covered in grease. I saw a clown that ate with his dirty hands. My grandmother would die if she saw him. I wondered what kind of life he led and what kind of food they ate in Zondi? But my grandmother would not allow me to visit. ‘He’ll put you in a taxi,’ she told me. ‘It’s not safe. It has no seatbelts.’”

Before her teens, Khanyi could only see her father outside the house. He was not allowed in. Later, she would drag him to family events though he wasn’t invited. “I would pull him into the house to gatecrash,” she says. “I wanted him to meet my cousins and aunts. He’d sit in a corner and have scones and tea but he’d always want to leave right away. I pleaded with him to stay. I longed for his company.”

Menzi would sneak into the neighbourhood and pick up his daughter in secret. He would spoil her with sweets and cash. “He was my Father Christmas,” Khanyi says.

“He’d take me to his scrapyard and show me cars in Dube. I would play under them and have magwinya. He would ask me not to tell my grandmother but whenever I was upset with her I would shout things like ‘My dad said you are evil and he will come and steal me – he loves me!’ Then he would get in trouble with her. She’d warn him not to ‘mess up this child’ and then he’d get angry with me because I didn’t know how to lie. But I couldn’t help it. I grew up in an honest house. Nevertheless, I loved my dad. He was my clown. I felt that no-one understood him.”

Menzi had children with other women and over time Khanyi got to meet her four half-sisters and six half-brothers. No bonds ever took hold, except for Thandeka, with whom she became very close and who still plays an important part in her life today. At some point Menzi tried to reconcile with Khanyi’s mother, Lynette. “But she would push him away,” Khanyi says. “I saw the commotion between them but it didn’t regsiter in my kid mind. Still, I know he was fond of my mother.”