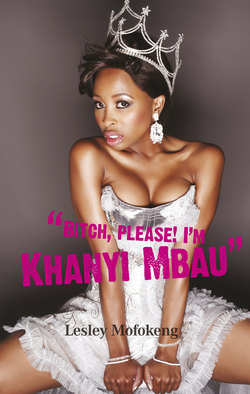

Читать книгу Bitch, please! I'm Khanyi Mbau - Lesley Mofokeng - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2. A star is born

ОглавлениеKhanyi went to a whites-only crèche called Flock on Eloff Street in downtown Johannesburg. Persuasive and professional, her mother Lynette managed to sneak her in. She and one other child were the only black kids allowed. Khanyi travelled there daily with her mother, who worked in one of the nearby big office blocks. Wendy, the founder of the school, had emigrated to South Africa from England and had no hang-ups about racial mixing.

“We’d hug and drink from the same cup and grab sweets from each other’s mouths,” she recalls. “That never bothered Wendy so I grew up in a world where blacks and whites were equals and I never really experienced racism. Except for this one time.”

Her friend Laris was a beautiful coloured girl who passed for white when that sort of thing mattered. Khanyi visited for a sleep over but felt out of place. Laris’s mother was good to her, but her boyfriend gave her strange looks. “It made me feel like I was black and dirty,” Khanyi says. Later that evening, she heard Laris’s mother and her Afrikaner boyfriend arguing in the room next door. “I don’t understand why this black child is always here,” he said. Khanyi pretended everything was fine in the morning but never went back.

Surrounded by blondes and brunettes with piercing blue eyes at the crèche, she noticed there was something different about her. “I hated my hair,” Khanyi says. She couldn’t stand that it was hard and didn’t billow in the wind like the hair of the women she saw on TV. She especially wanted long hair, so her mother got her braids. “At least they could fly in the wind like my classmates’ hair,” she says.

Her blackness meant she stood out sometimes. “My classmates would say they loved my skin and Gabriella, a blonde with blue eyes, once asked if I tasted like chocolate. Then she licked my face for a ‘taste’ and said, ‘You taste salty’. I asked her if she tasted like vanilla ice cream and then licked her too. She also tasted salty.”

Khanyi lived in contrasting worlds – in the city where she was comfortable and in the township amidst poverty. But still she had a far easier life than most.

The Mbaus lived in an eight-roomed house on Mzoneli Street in Mofolo Village and her grandmother drove a Mazda 626. They made hug-a-bug cupcakes and listened to jazz. Township kids would pull her hair and called her “Khanyi, mlungu” (Khanyi, the white person).

“I watched them eat out of cans with their bare hands and pretended it was normal,”Khanyi says. “I played along so I could fit in.” But she played in brand-new Woolworths clothes and shiny shoes, outfits the township kids would only ever wear on special days – if at all.

She became friends with Portia who lived across from the Mbaus, a chubby girl who didn’t quite fit the mould of a township girl either. She also spoke English far too well and her parents worked at good jobs in town, like Lynette did. “We became friends out of necessity,” Khanyi says. “We were both the odd ones out.”

Khanyi enticed Portia over with Zippy Toys, stoves and pots her Aunt Nikiwe had brought from overseas. Khanyi hid them from other children because she was convinced they would break or steal them.

Life was good in the Mbau house. There was always fancy fare like spaghetti bolognaise and lasagne, French toast, poached eggs, croissants and koeksisters. She lived on home-baked brownies, gingerbread men and chocolate-chip cookies, drinking glass after glass of Nesquik. She tasted expensive chocolates like Ferrero Rocher, Lindt and Kinder Joy at a young age, thanks to her aunt’s duty-free shopping sprees at European airports.

“I’d lie on the couch drinking Coca-Cola,” she says and explains that most township kids are banished to the floor. “I could never understand the normal black child’s upbringing. I never understood how eight people could sleep in a four-roomed house with only two bedrooms, a kitchen and a lounge. It overwhelmed me that so many people could share such a small space. I was like ‘Geez, how do they do it?’”

In Khanyi’s privileged little world, every girl had her own bedroom with a bed and a mirror to gaze at herself as she brushed her hair.

But life was strict, too. During the week, the rule at her grandparents’ house was to be home before the curtains were drawn at 5.30pm. On weekends, Khanyi could only leave the house after midday. She could never play hide-and-seek with the other children because she arrived late and by then the teams and alliances were formed.

She would get a beating if she broke the rules. Her grandparents were strict and old school about discipline. Portia’s much younger parents didn’t mind if she got home late in the evening. Khanyi thought it was very unfair. She and Portia spent endless hours avoiding the scary township streets, watching old black and white movies and Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous, with the mansions and cars owned by Hollywood stars. It was all so glamorous and magical to two lonely township girls.

Khanyi spent hours watching her favourite TV shows like The Smurfs, Gummi Bears, Mina Moo and Power Rangers. She also loved Kideo Kids, Galubi and Swartkat.

When her granddaughter was not lying on the couch, Grandma Gladys ensured that she was exposed to the best popular culture had to offer – the music of Frank Sinatra, Billie Holiday and Harry Belafonte. Khanyi knew every word to their songs. The sound of trombonist Dixie Lindt filled the house. Her grandparents also told her about Martin Luther King and the momentous achievements of the African-American civil rights movement.

The Mbaus were big on church. It took up every Sunday. “My family was heavily involved at the Faith Ways Church in Orlando East. My grandmother was a hostess and my mother sang in the choir. Religion was huge in my grandparents’ house and swearing was not allowed. My grandmother still thinks I don’t know how to say sh*t or f*ck.”

Khanyi jokes that she went to church so much growing up that even after all the years of absenteeism, God still recognises her! “I still know every scripture in the Bible,” she says. “I even quote from it on Twitter.”

The family had a punishing schedule of devotion. They reported for church duty from 6am till 6pm on any given Sunday. They arrived early to clean the building and pray with the pastor. They stayed for the 8am to 10am service, then the 10am to 12pm service, and finally the 12pm to 4pm scripture services that included premarital counselling. Khanyi attended all the teen and young adult classes. Then they’d clean up from 4pm to 6pm.

Khanyi lived a morally correct and sheltered life growing up. She was very religious by virtue of her environment. It meant she was an easy target.

“I never knew there were bad people who could visit pain on you,” she says. “Or even that people lie. I thought the world was a warm, safe place where we all sing ‘Khumbaya’. I was always in tears when other kids were horrible and said mean things, especially when they teased me about my deep voice and called me ‘Khanyi mlungu’.”

She would go on to develop a thicker skin and learn how to stand up for herself. She learned by fighting her mother’s battles, for instance, by telling her not to sit next to a particular taxi passanger because he “looked funny”. “When we had to wait for a taxi and it took long to arrive, I would tell my mother: ‘Don’t worry, Mommy, I’m going to buy you a taxi that goes straight from town to Mofolo’. I would always say, ‘I love you, Mommy, thank you, Mommy’. Other passengers in the taxi would ask my mother why she was raising me like a white person.

“Looking back, I realise that I fought my mother’s battles. She is naturally timid and soft. Whenever there was a clash, I would be next to her shouting: ‘Leave her alone, leave her alone!’ I stood up for her all the time.”

Khanyi wanted to be on TV from a young age. She knew she could do it.

In a way, she was born ready for her “discovery” at Cresta shopping centre at age eight. Discovered during an emotional moment just like Charlize Theron (who reportedly had a tantrum in a bank), Khanyi was overexcited about a hat her mom had just bought her. Apparently the innocent joy she displayed jumping up and down while singing a Care Bears song caught the eye of a passing talent scout casting for Red Pepper productions. They invited the Mbaus to an audition.

By then Lynette had already signed up her daughter with the Professional Kids agency in Melville – and here was her child’s big break. When she arrived, the first thing Khanyi asked was, “When do I start to work?” Everyone laughed at the cheeky little number but she meant it and her bravado paid off. She was instantly cast as one of the Galubi children. Later she became a Kideo Kid, then a Sasko Sam presenter, visiting schools to give away hampers and bread. Khanyi had crossed the threshold from reality into television. She was through the looking glass and on screen. Brand Khanyi had begun.

Her first salary cheque was for R600. She was eight years old and Lynette let her spend it all in one go. It was the kind of thrilling shopping experience that must feel like freedom to a child. Sweet Khanyi also offered to buy her mother a house of their own, because she knew her mother wanted to move into her own place. Lynette was a smart, independant career woman and living with her parents did not fit in with her plans.

Lynette took her daughter to a toy store in Eastgate Mall. It was to be Khanyi’s first shopping spree – the first of many. She bought four Barbies, four Kens, a doll’s house and a stove, plates, a mini TV and hi-fi system, plus a bomber jacket with orange lining. She was in consumer heaven.

But after she had done all her shopping, Lynette popped the balloon of fun and turned the jaunt into an important lesson. It was the first and last time she was allowed to blow money like that. From then on she was expected to save every cent. In her teenage years, when tragedy hit the family and they battled financially, Khanyi’s modest savings would help to pull her and her family through.

Being a child star and a responsible scholar is not easy. It has to be a well-coordinated juggling act between professional commitments and studies. It takes discipline. The lure of the cameras always trumped school for Khanyi. Being on TV was way more fun than algebra. She was often chased out of her class at Milpark Primary for being unruly. Khanyi remembers listening to the thick Cockney accent of Mrs Patta, her English teacher, which put her to sleep like a tranquiliser.

At least there was the refuge of Mr Stevens’ drawing and pottery class. Khanyi loved making collages. Images smashed together. She was devastated when he died of cancer in 1994.

It also didn’t help that she had been diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder at age seven. She only took medication for it for a short while, because her grandmother didn’t believe it to be effective. She was therefore easily distracted and bored in class, counting the minutes until she could escape from Milpark Primary at 1.30pm and rush over to the nearby SABC studios for taping. The experience proved she wasn’t like the other kids. She had talent. It was her name in the credits.

School could never compete with all that attention. As Khanyi puts it, looking back at that exciting time and the first flush of success: “I knew that millionaires were not in school. Teachers are not millionaires. My father would castigate me. He told me to take my school work seriously but I knew I was meant for bigger things. School simply was not for me. I was passionate when I said this to my father. I believed it – I knew my destiny.”

As she grew older one thing did get her attention: Grant Solomons, the fastest runner in school. He was the “it” boy. Well built with broad shoulders, thunder thighs and the cut calf muscles of a committed athlete, he was Khanyi’s first genuine crush. Even better, he liked her too.

Ever proactive, Khanyi bought him a rose and sent him a love letter on Valentine’s Day of 1997 in which she declared her undying love and everything that had to do with the birds and the bees. But her mother wouldn’t allow her to attend the Valentine’s Day dance with Grant, so he didn’t get to put the special chain he’d bought for her around her neck that night. Finally they shared their first kiss a while after Valentine’s Day. Grant was to be her first boyfriend, but not her last.

Her sudden fame was a mixed blessing at school. There was inevitably a lot of jealousy when Khanyi became the school’s “celebrity” but even then she was good at owning it. Khanyi didn’t make a big deal out of her fame. She seemed to wear it well, as if it was a natural event – something she had deserved all her life.

So when students said mean things about her, she held her head high. She knew they would trade places with her in a heartbeat. It was early training in managing envy. Khanyi was always good at looking like she was meant to be the one getting all the attention. It was effortless to her. The fame was a good way to notice who was worth getting to know. If other students couldn’t handle it, then they really weren’t meant to be in her life.

Not that Khanyi’s grandmother Gladys took much notice of her granddaughter’s “fame”. The Mbau household remained as strict as ever. Despite being on TV in the lounge, Khanyi was still expected to clean it. She wasn’t excused a single chore. Gladys carried on as if nothing had changed and Khanyi was furious but eventually came to depend on that normality. She would always be a kid in her grandmother’s home and that was comforting in the crazy times to come.

That early validation remains a huge emotional resource for Khanyi. It drives her. She used the fact that she wasn’t like the other kids in a positive way. It became a source of strength and self-esteem – the basis of her sense of entitlement. “I’ve never felt inferior,” she says,“despite all the snide remarks, bullying and mean stares. I had it in my head that I stand out. I grew up with that mentality.”

When Khanyi turned nine she moved in with her mother, who had bought an apartment at Dudley Heights in Hillbrow. Khanyi said goodbye to her beloved grandparents and left ekasi for the big city.

Her mother’s social circle and lifestyle was very much of the era. Mandela was free, the ANC was unbanned and the country would never be the same. It was the eve of the watershed 1994 non-racial elections. Black people would soon be going places fast. Rising up in business and enjoying new opportunities. Khanyi was surrounded and influenced by her mother’s friends, who were ambitious, well-educated, independent women. This was the new South Africa.

You only had to look at Lynette and her sister Nikiwe’s nails to know they meant business. They were always shiny and immaculately manicured. They were up on the latest fashion trends. They partied with the celebrites of the day – popular actor and radio presenter Treasure Tshabalala and Metro FM DJs like Lawrence Dube and Stan Katz. Khanyi was exposed to the social life of celebrity early on.

“I was tossed around in that world as a little girl,” she says. “They’d carry me around on their shoulders to the music of Sankomota and I’d sing the words to the songs. They were the happening professionals on the block and I was running around at their parties.”

Lynette was glamorous and knew how to play the hostess. “At their soirees, my mom would change four times. She arrived in a dress, then a change of costume for dinner, a little number for drinks and then an after-party look. My mother was my Barbie doll. She had the most amazingly beautiful figure and she spoke so well. Growing up in that world and given what I saw on TV, I knew I wanted to be rich and famous.”

Khanyi was growing up and she needed a father more than ever. Moving towards her emotional teens she felt his absence in her life and longed to have a real bond with him. She envied her white classmates who spoke lovingly of their dads. She even colluded with her father to have her removed from Milpark Primary to a school closer to him. She became a school hopper and moved to Meredale Primary in the south of Joburg in Grade 7.

Khanyi had triumphed over the teasing at Milpark thanks to her outgoing personality, and her TV fame meant she was very much the queen of the cool clique at Milpark. At Meredale she had to start all over again. She had hoped her half-sister Thandeka, who was already there, could take care of her and introduce her to her circle of friends. But Khanyi was younger and new and Thandeka could only do so much. The TV star ended up feeling like an outsider.

But she had bigger problems. A tug of war was developing between her parents who had both married other people around the same time. The secret wish that her parents would get back together was gone. To make matters worse, her mother had a baby. Khanyi had been the only child, the centre of attention, for 10 years until this little creature with the button nose called Buhle appeared.

“It was a tough year for me,” she says. “My mother had a child and I didn’t think my father loved me that much. I moved schools and my TV work ended – I felt betrayed.”

Her new baby sister was a rival. She’d already gone through rivalry for affection with her father and his children. “I always felt like my father loved Thandeka more than me. She was academically inclined and excelled in class. She loved educational toys while I was into Barbies. But at least I bought them with my own money. Thandeka’s head was always buried in books.”

If only Khanyi had done the same. She failed Grade 7.