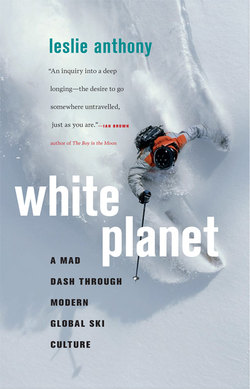

Читать книгу White Planet - Leslie Anthony - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3 IN TO THE DEEP

One can never be bored by powder skiing because it . . . only comes in sufficient amounts in particular places, at certain times on this earth; it lasts only a limited amount of time before sun or wind changes it. People devote their lives to it “for the pleasure of being so purely played” by gravity and snow.

DELORES LACHAPELLE, Earth Wisdom, 1978

THR EE HOURS earlier I’d been asleep on a bunk in a Christchurch youth hostel. Now I stood atop a ridge overlooking the steep, snow-choked bowls of New Zealand’s Mt. Hutt, the once so-called “ski field in the sky.” Hovering 6,000 feet above the town of Methven and the green and brown patchwork of the Canterbury Plains, I watched as surf-raised punk Maoris bedecked in wetsuits and zinc warpaint zigzagged through swinging T-bars (drag lifts on which two riders are pulled uphill on an inverted “T”) on waves of Southern Alps snow. On the lodge decks, sheep farmers in generations-old gear tipped back quarts of Steinlager amid the screams of obnoxious keas, the eagle-like mountain parrots best described as green ravens with even more attitude and smarts. Visible from Mt. Hutt’s precipitous ridges were several small ski areas lodged in surrounding high-alpine cirques. These “club fields”—thrown up and populated by the most core of NZ’s hardcore ski families— were places you couldn’t even imagine placing a lift, though each was strung with a single T-bar, poma, rope, or, in some cases, cable that you wore a belt to hook into and that was locally referred to as a “nutcracker.” I blinked, filing away the exotic tableau, and dropped into two feet of the only kind of snow that really matters.

My final ski-bumming stint (discounting, many would argue, my current job) was another summer sojourn between university degrees. This time I’d gone looking for powder on the neglected side of that initial coin toss. Alone again, burdened by less and lighter gear (I was now exclusively a telemarker), I’d landed on the South Island one September and hitchhiked, bused, and ferried my way around the country. I skied volcanoes on the North Island, spent a hungry week in a mountain hut waiting out weather in an attempt to climb and ski NZ’s highest peak, Mt. Cook, and traipsed through most of the nation’s major ski areas. But oddly— or perhaps not—my biggest adventure came on the road.

After news of a big snowfall in the resort hubs of Queens-town and Wanaka, I hitchhiked south from Christchurch, catching my first ride through the folded-cardboard landscapes of the South Island with a sheep rancher. He dropped me in the middle of nowhere, then headed west on what seemed barely a road toward a vast sheep station in the foothills of the Southern Alps. How big was his holding? He rounded up his sheep with a helicopter. I watched the diminishing dust cloud marking the retreat of his rattling pickup for a long while.

After an hour, a car finally materialized on the horizon. It appeared to be bouncing down the road at high speed. It was a dirty-gold, American-made station wagon (most cars in NZ were British or Japanese); the back was stuffed with ski bags, duffels, and assorted gear; random items like a boot, a glove, or a beer bottle were pressed against the windows like a storefront sale. The two occupants seemed to be fighting with each other over the steering wheel as they blew past at well over sixty miles per hour. But just as I dejectedly dropped my thumb, the car screeched to a halt, then backed up, burning rubber. A couple of long-haired, smiling faces beamed out.

“Sorry mite, didn’t see ya skeeez theea . . .”

“Yeeh, we wuz wristling . . .”

“. . . but then Jiff heea sees ’em lyin’ in the greevel, heh?”

“. . . yeeh, and so I scream ‘skeea!’, and Geerrett heea . . .”

“. . . pulls over, so . . .”

“. . . hop een!”

There’s a fine line between the ride you’ll never forget and the ride you wish you’d never taken. That line was somewhere in Geoff and Garrett’s car, but as with everything else in the vehicle, no one quite knew where.

The hyperkinetic pair were speed skiers on the NZnational team. Of skiing’s numerous insane disciplines, speed skiing is by far the most certifiable. In the sport’s equivalent of drag racing, racers squeeze into aerodynamic suits and helmets, don long, heavy skis, then hurtle down a steep, straight track until they reach maximum velocity and pass through an electronic speed trap. Where the track flattens—the beginning of the long glide to a stop—skiers are often going so fast that their bodies can’t handle the sudden compression. So they crash. Sometimes they catch an edge on the track. And crash. Sometimes the air gets under their skis and lifts them off the snow like a hydrofoil so they lose control. And crash. Sometimes they crash . . . just because. In any case, skiers can be torn apart, breaking bones that only the tight suit (similar to motorcycle leathers) keep in place.

Conversation revealed that these guys were friends with speed skier Steve McKinney, one of my favorite powder mag heroes. Where thrills were concerned, McKinney had done it all: first to break the 200 km/h barrier (125 mph; it has since pushed past 250 km/h, or 150 mph), summited Denali, paraglided off Mt. Everest.

“The faster my body travels, the slower my mind seems to work. In the crescendo of speed, there is no thought, no sound, no vision, no vibration. It is simply instinct and faith,”6 McKinney famously offered of the womb-like calm inside his self-designed Darth Vader helmet.

Recalling this might have told me what I was in for. Geoff and Garrett were drinking beer and showed me how they made the car bounce by simultaneously jostling up and down in their seats. Then some high-powered NZmarijuana appeared. I tried not to imbibe, but it was useless: the car was seriously hotboxed and one hit was more than enough. Which made it that much more intense when, at the top of a several-mile downhill, with no warning, Garrett climbed out the passenger window and crabbed across the windshield to the driver’s side, reaching in to hold the wheel while Geoff slid across the seat and also went out the passenger window to lie on the roof facing forward. Garrett then positioned himself similarly on the driver’s side roof, with his left arm still holding the steering wheel. Both were laughing like hyenas. I was alone in the backseat of a car hurtling down a mountain.

Clearly practiced, the maneuver took wordless seconds to execute, and there was no time to be scared. I’d passed instantly through a state of terror into acceptance of whatever fate was in store. Kind of like falling off a building.

Were near-death experiences the way these guys pumped up for a speed-skiing meet, I wondered? I was aware of the absurdity of posing this question while hanging out of the car with one arm propped in the window and the other arm on the roof. I was also aware that neither of them was watching the road while answering.

“Ow, weea not gowin’ to anee speeed-skeeing thingie . . .”

“Now, weea gowin’ to Wanaka . . .”

“. . . to geet in a heelicopta . . .”

“. . . and skee some powda.”

Of course. Even skiing’s most depraved shared the thirst.

WHEN DOLORES LaChapelle died in Silverton, Colorado, in January 2007 at the age of eighty-nine, the hagiography began immediately. And why not? Sure, you wouldn’t find any cheesy dashboard figurines of the woman with the long silver braid and beatific smile offering blessings to acolytes in ski-town souvenir shops, but she was still the closest thing powder skiing would ever have to a patron saint.

Fêted and remembered everywhere, LaChapelle’s considerably charmed life was rewoven in obituaries around the continent. Suddenly, a lot of people who’d never heard of the author, mountain sage, and driving force in the deep ecology movement, knew who Dolores LaChapelle was. Equally suddenly, many who’d never had cause to ponder such things learned that “powder”—the catch-all euphemism for unconsolidated, preferably deep snow—was a relatively new concept.

Deep ecologists consider humans an integral part of the environment and value human and non-human life equally. In this view, skiers who claim, “It’s all about powder,” are referring not simply to a substance but to their movement through, and thus relationship to, that substance. LaCha-pelle, who was ground zero to the idea’s development and philosophized extensively on the subject, saw this relationship in purely Zen terms: the snow’s molecules over here, your little clump of molecules over there, no difference between you and a tree, you and a table, you and frickin’ Madonna.

Most ski stories begin with or center around the quest for powder, and once again, Arnold Lunn, in The Mountains of Youth, presciently describes why:

The true skier . . . is not confined to a piste. He is an artist who creates a pattern of lovely lines from virgin and uncorrupted snow. What marble is to the sculptor, so are the latent harmonies of ridge and hollow, powder and sun-softened crust to the true skier. By a wise dispensation of providence, the snow, whose beauty has been defaced and destroyed by the multitude of piste addicts, does not record the passage of the [racer]. It is only soft snow that records the movements of individual skiers, and it is only in soft snow that the real artist can express himself.7

Art and science are indeed inseparable when it comes to powder, for its every aesthetic is based in chemistry and physics: the basic shape and geometry of flakes; the loft and water content of newly fallen snow; the downy hoar crystals that grow on powder’s surface in cold weather; the sweep of a drift in a swirling wind; the shadowed compression of a ski track; the contrail of vaporized crystals billowing behind a skier.

Indeed, no substance on Earth is as transformative as snow, which, perhaps, isn’t surprising given that no other element has the chameleonic properties of snow’s precursor, water. And no other type of snow has the mutative capacity of powder. It is there and then it is not, settling, consolidating, moving with the breeze, deliquescing in the sun. Morphing all too quickly, it reminds us that the two-million-year-old blue ice on a glacier’s face was once the stuff of face-shots.

Nothing on Earth compares to walking through falling snow. And gliding effortlessly through it? Well, you’re crossing the welcome mat of an entire book devoted to why this prospect is such a powerful psychological trigger for skiers. Something about tumbling flakes draws you out, teases the id into consciousness. This is the trait we most appreciate; doubtless anthropological in nature, it is a Paleolithic holdover buried somewhere in our Cro-Magnon genes. You’re aware of a hovering desire to do something, be part of it. Think snowmen and toboggans. At the same time, this new and subtle beauty seems to steer your attention from mundane concerns and make fast the moment with a host of new sensations. There’s the cold, fresh, metallic smell and the sudden pervasive quiet. That which is typically invisible is revealed: footprints, animal tracks, and the eddying currents of wind. And the ultimate paradox of the world’s familiar tracings becoming more apparent only because they’ve disappeared beneath an entirely new iconography: drooping hats adorning posts, mounds bowing over branches, and the white-lipped geometry of urban skylines; it is a land where, suddenly, every angle is curved, every curve flattened, and every flatness mute.

It’s not just art and science, but music and math as well.

When Canada’s prime ministerial enfant terrible Pierre Elliott Trudeau famously contemplated his (first) retirement while walking in an Ottawa blizzard one night, not a single Canuck of any political stripe thought it a stupid or unconsidered way to make a decision: we’d all been there, we all understood. Snowflakes both speak and listen. Making decisions in a snowstorm is our birthright.

Powder, then, is inarguably transformative to the human spirit. As skiers, powder is our medium, and the medium, as Marshall McLuhan pointed out, is the message. Descending in powder offers an indescribable sensation that clearly speaks to a primitive pleasure center of the brain, for it instantly demands more in a classic addictive cycle. And yet, unlike water, powder is fundamentally changed when you pass through it: just as there is no concept of untracked water, so is there no concept of inviolate powder. This isn’t just philosophy, but morality as well; snaking someone else’s powder line—an irreplaceable commodity— is considered a contravention of skier decorum.

Let’s back up a bit. Powder wouldn’t exist if someone hadn’t figured out a way to ski it. It could just as easily have been a failed experiment, maybe not as bad as Evel Knievel’s attempted motorcycle jump across the Snake River Canyon, but still a natural phenomenon that no human tool or technique could conquer. Before humans deigned to sub-categorize it, in fact, the white stuff falling from the sky was all just snow. Even if they’re variously affected by the depth, weight, and water content of the snow that’s falling, mountains, forests, and waterways have no capacity to differentiate. Humans, however, can and do: the Inuit famously (or mythically) have many words for snow, to describe its worth in construction and travel and to predict whether you’re about to fall through it into the Arctic Ocean. And though skiers have no word for “snow mixed with the shit of a sled dog,” we’ve developed a similar snowcabulary. Simply put, skiers invented powder, imagining it into existence from the stacks of crystals piling up on mountainsides around the world.

Ironically, it was a ski racer from Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, named Dick Durrance who, in 1940, started the modern powder ball rolling in Alta, Utah. Having opened a resort and started a ski school, he was dealing with the local overabundance of snow and a glut of terrain on which stemming (in which one ski at a time was pushed into a turn) wasn’t possible. It was clear that regular skiing— as practiced preferentially to this point on packed snow, pistes, and racecourses—wasn’t going to cut it here. Alternate techniques were required, so Durrance invented the short-swinging, up-down “dipsy-doodle” powder turn, which quickly became the resort’s signature export.

Meanwhile, a young Dolores Greenwell was skiing around Loveland Pass, Colorado, on a pair of six-foot-plus hickory skis. From 1947 through 1950, she taught skiing in Aspen, developing a nose and a preference for the untracked snow away from the lifts. In 1950 she made the first ski ascent of Mt. Columbia, second-highest peak in the Canadian Rockies, and the first ski ascent of Snow Dome, the continent’s hydrographic apex. After she married Ed LaChapelle, a Canadian geophysicist she met on that trip, the couple spent time at the avalanche institute in Davos, Switzerland, before moving to Alta, where Ed was stationed on the U.S. Forest Service’s avalanche and snow research team. Dolores, naturally, was there to ski. In 1956, she and Jim Shane were the first to dipsy-doodle down Alta’s infamous Baldy Chute—in powder so deep they disappeared.

FOR MANY PEOPLE, skiing is a sphere of perpetual freedom into which they can step at will, and the sweet spot—that which instantly expands the sphere in every dimension—is powder. Whether one is in it or simply wants to be, powder is a realm of constant challenge. It is about words, but being unable to speak; about telling, but being unable to describe. It is sensations and memories. Silence amplifying a heartbeat and the rasping of breath. Involuntary grunts of effort and unconscious squeals of delight. Inspiration. Bad poetry. Broken marriages. Magazines. Movies. Grins. Silliness. Frozen toes and ice cream headaches. Magical turns and occasional smacks off a hidden hazard. First tracks. Lost skis. Trudging, navigating, and skiing over, through and around boilerplate, sastrugi, crust, slab, crud, and other snow-junk just to get to the good stuff. A way of feeling. A way of thinking. A way of life. A way, period. Tao.

“Our culture has no words for this experience of ‘nothing’ when skiing powder,” LaChapelle put it in 1993’s Deep Powder Snow: 40 Years of Ecstatic Skiing, Avalanches, and Earth Wisdom. “In general the idea of nothingness or nothing in our culture is frightening. However, in Chinese Taosit thought, it’s called “the fullness of the void” out of which all things come . . . My experiences with powder snow gave me the first glimmerings of the further possibilities of mind.”8

She was onto something.

It has been said that if joy is the response of a lover receiving what they love, then this is the joy we feel skiing powder with friends. Overflowing gratitude indeed seems to paint the absolutely absurd grins flashed at the bottom of a run. You never see such grins elsewhere—not on a tennis court or a golf course, not on a podium or in a dance club. No flush of physical victory compares to the ineffable euphoria of a journey through powder. It isn’t just shared fun but, as LaChapelle also notes, a sense of life fully lived, together, “in a blaze of reality.”

In the end, powder isn’t about an outer experience but an inner one, a crucial intersection of mind and body where thinking and feeling cannot be teased apart. This is where immersion and affliction, submergence and addiction live, forever invoking powder’s unique spirituality as religion. Yet this sport’s recently canonized angel would loudly eschew any traditional doctrine in favor of making no distinction between the universe at large and anything within it; no distinction, for instance, between saints and sinners, powder snow and powder-snow seekers, the places you look for it and the places it is found.

When—as I’d found in my travels—you got right down to it, the essence of skiing is best summed by the equation: soul/X = people + places + powder. Surely there was some kind of heaven on Earth where this equation was always solved.