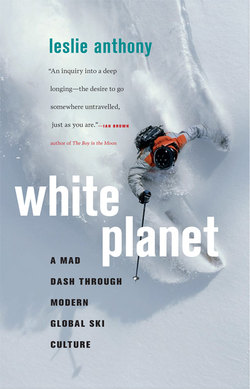

Читать книгу White Planet - Leslie Anthony - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE : LEGEND

Skiing . . . is positively thrilling no matter how well or poorly you’ve mastered it. From the . . . moment you begin to slide over snow, feel the tug of gravity pull you downhill, your heart and spirit exults. It is pure thrill. There are, to be sure, more than a few moments of frustration . . . But even during that painful period, there is a constant thrill . . . Once the basics have been reduced to muscle memory, skiing is a non-stop celebration of how good life can be when you live it at the edge of your self-defined envelope, be that envelope green or double black.

G.D. MAXWELL, Pique Newsmagazine, April 9, 2009

I CAN BARELY remember what I did yesterday, but I clearly remember my first day of skiing. Well, maybe not clearly—more like an old Super 8 movie—but you get the picture.

Housebound on a gorgeous spring-break day sometime in the late sixties, my hyperkinetic friend Mike and I were driving my mother nuts with loud Hot Wheels races and house-wide G.I. Joe battles. In a fit of desperation, she insisted we take some dusty ski equipment that was languishing in the garage—unused since the early fifties—to the nearby Don Valley Ski Centre, a riverbank operation in one of Toronto’s newly minted suburban wastelands, and give it a whirl.

“It’ll be more fun than tobogganing,” she said, pretty much selling us.

We wrapped chubby hands around wooden, enamel-painted skis with bear-trap bindings, bamboo poles, and boots far too big for grade-school feet, and schlepped it all to the hill. It was an arduous journey of an hour or so, and when we arrived, impatient and excited at the sight of people zipping down the slope, we still had to figure out how all this equipment worked.

We struggled with the stiff, cumbersome boots, cables, springs, and myriad straps for what seemed an eternity. The bindings seemed to defy any law of engineering gleaned from Meccano sets, Lego bricks, or tabletop hockey, but when the forward throws on the cable finally snapped down, it seemed the boots were attached to the skis. It didn’t last. With each tentative step the bindings would let go, leaving us ski-less and frustrated. Only through the sympathetic intervention of adults who witnessed our comic plight (tsk-tsking over what kind of parent would cast neophyte children adrift like this) were we eventually affixed awkwardly to the planks.

We quickly mastered shuffling ahead on the skis, and eagerly got in line for the tow. As we waited our turn, I watched the fat hemp rope whiz around a small truck wheel driven by a chugging diesel engine and studied the loading procedure. It seemed simple: tuck your poles under one arm, place one hand ahead of your body, another behind your back, and grab the rope. Which was just what I did. My arms were practically ripped from their sockets as I saw snow, then sky, then snow again. I could hear the slurping, wet whoosh of a body being dragged through snow, the clack-clack of skis clapping together, and Mike’s hysterical laughter. My eyes, nose, and mouth filled with snow. Finally, I’d let go of the rope.

I felt sick. The tow operator picked me up and shepherded me back to the line, where I had the satisfaction of watching the same fate befall Mike. Each of us tried a second time, with a similar result. Beaten, we sniveled around like wounded puppies until, again, someone offered to help. When we eventually made it to the top, it was like we’d been airlifted from hell to well . . . we weren’t sure what.

The speed of sliding downhill was dizzying and intoxicating, the frequent wipeouts brutal and instructive. We continued to have our arms yanked numb by the speedy rope tows, fall backward off a platter lift—a spring-loaded metal pole with a plastic disc you tucked through your crotch to pull you along, itself a novelty—and skid helplessly downhill upside down, we plowed full-speed and out of control into hay bales, and generally took a massive beating from the tiny 115-foot vertical. The most vivid frames from this flickering film, however, are not of motion but notion—how it all looked and felt to my uninitiated senses.

Between runs, we sipped scalding hot chocolate from a rancid-smelling machine and queued with tanned, sunglass-adorned hedonists who reeked of coconut and spoke of Collingwood and the Laurentians, the Alps and Banff. Everyone but us—clad in jeans with flannel pajamas dangling below the cuffs—wore sleek, black stretch pants that disappeared into their boots. Smart knit sweaters, turtlenecks, and headbands out-polled jackets, scarves, and hats, making a James Bondian damn-the-elements fashion statement. European labels were legion—Piz Buin, Snik, Vuarnet, Carrera, Arlberg. This leitmotif created the very real sense of mountains, something I knew only from picture books. Amid a monotonous suburban landscape we discovered a window onto a world apart. I stared long and hard, not realizing I was viewing a tiny corner of a worldwide diaspora, an entire galaxy of alpine travel, history, and endeavor.

Mike and I were too battered to walk home, and we sheepishly used our last dime to call my mother. She cried when she saw us: we were broken, bruised, and bloodied, our pajamas shredded by rusty ski edges, the palms of our mitts torn out by the rough hemp of the rope tow. Consumed by guilt, she overlooked our shit-eating grins and did what any conflicted parent would: screamed at us for not calling her sooner.

“It’s OK, mom,” I smiled, unaware that I’d just experienced the closest a human can come to flying without leaving the Earth. “We had fun.”