Читать книгу Goddess of Love Incarnate - Leslie Zemeckis - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

1994

A SEPTEMBER DAY IN LOS ANGELES. NOXIOUS, SMOG-FILLED WAVES OF brownish heat bear down on the desert city, smothering everything under a grimy cloud. Sprinklers shut off as the city feared another water shortage. Grass turned yellow, bleached of life. Everything is brown. The air. The land. It is an ugly time of year. It is nine months past the Northridge earthquake, when the San Fernando Valley shook, hardly felt in Hollywood. Where she lives.

The apartment is within walking distance of Paramount Studios where the greats such as Dietrich, Swanson, and Pickford used to pull their chauffeur-driven Bugattis and Duesenbergs and Mercedeses through the tall iron gates immortalized in movies such as Sunset Blvd. She too has been driven through the legendary gates to work. If she had known then how her life would end, would she have glanced down the treelined street and warned her younger self, or would she have continued down the path she was on?

The apartment is placed well back from the street, an old 1920s Spanish triplex. Built by Paramount Studios for the starlets and quite possibly studio executives’ trysts with the same. It was rumored Gloria Swanson once kept an apartment there. W. C. Fields’s mistress had another. The front room, though not large, is comfortable and would have been sunny if she ever opened her tattered curtains. It is a lower-floor unit with a thick wooden door. Quiet blankets the interior. A place of retreat. Cats roamed inside and out. A few mewed at the back door off the tiny kitchen that was never used. Most people thought the stray cats her only companions.

In the living room facing the expanse of green lawn and tall trees rising outside the French windows, she lies in bed. She had always had a bed in unconventional places. Her bed had been her stage. It still was. This time for the last act of her life.

As a child her bed had been tucked into a corner of the sun porch because there had been no space for her own room. They had been so poor back then, even before the Depression devastated the rest of the country.

And what a bed she had lounged on in her beloved home at the end of a wide twisting boulevard dotted with charming Craftsman cottages—oh! The remembered torment of having given that up—a big hand-carved wooden bed positioned smack in the living room. She had entertained lounging across it like Cleopatra sailing down the Nile, the banks of the river strewn with the carcasses of her lovers. She had played the Egyptian queen onstage, so why not in her home? That life long over now.

The bed, like so much else, was gone. Sold? She doesn’t remember.

She avoids the other residents of the apartment building. She assumed they knew she had once been the infamous . . . the notorious . . . the legendary stripper. Once. Thirty, forty years prior when Los Angeles still had some semblance of glamour. When one dressed to attend the nightclubs and she drank gin fizz and listened to jazz, though admittedly not her favorite music. Life had been more bearable. Or had it? She had certainly had her share of drama and heartache back then. Rushed to the hospital. Stomach pumped. Another divorce. Romance. Another terrible headline. Robbery. Pills. Always the pills.

She was seventy-seven years old. She had been terrified to grow old and ugly. The thought depressed her. As much as her spine was stiff and she experienced difficulty in bending, she wasn’t yet bed-bound. The arthritis hadn’t yet racked her body constantly. She had never been a person not moving. She had been a restless soul traversing from nightclub to theatre, from husband to lover, always on the move. A gypsy dancing her way through life, the wreckage of others left behind. Was it relief or torture to now be confined to a single place, nowhere to go?

Her wings have long been grounded. Flight no longer possible. Except in her mind. Her dreams are the only thing that take her away, that transport her crippled body away and above this modest apartment and the pain in her limbs and her heart and her desperate fear. A dread that has always been there, a terror that she had kept at bay until now.

Her mind could still travel where her body could not.

She lay across the bedspread that had once been fashionable and new. She looked at her arm hanging over the bed. Scarred. It was too damn hot to move. She had always liked the colder climates. “I’m a northern girl,” she would say.10 She should have retired to New York, but here she was, stuck in this suffocating putrid city, wilting and irritable. She had always enjoyed remarkably good health. She had rarely been sick. Rarely been without money either.

Now the only way she didn’t feel—pain or memory or regret—was with a system full of junk. A thick, heavy feeling would wash over her, taking away her apprehension. She would drift in pleasant nothingness, which was preferable to the here and now.

So much to worry about. Her bank was the cash in the pocket of her robe. A thin stack folded against her breast.

Wasn’t she the one who had flippantly told some reporter she always supposed there would be someone around to buy her a burger? She had made baskets full of money. Oh, how she had loved those baskets, decorated with pink ribbon, filled with crisp green bills.

She looked around the nicotine-stained walls that protected and imprisoned her. A dim light shone through her worn curtains, shutting out prying eyes. She didn’t want people to see her. She didn’t want a camera to capture who she was now. It pained her worse than the ache in her joints. She had never wanted to be forgotten and insignificant. But she was.

From the small table next to her bed incense burned, a constant, thin trail of smoke spiraling upward, mixing with the white cloud from her Salem cigarettes. From outside her apartment the smell was pungent. One of her fans joked, “Lili, people are going to think you burn incense to cover the smell of pot.” She thought that funny. “Good,” she said, “give them something to talk about.”11 People had always thought the worst about her. With her help. She had loved the headlines.

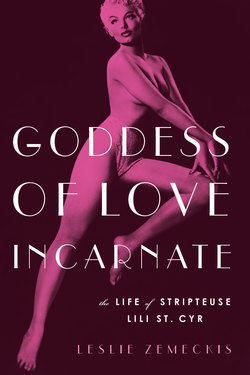

LILI ST. CYR IS ONE OF THE WORLD’S MOST EXCITING WOMEN.

‘I CAN’T SING OR DANCE,’ ADMITS STRIPPER LILI ST. CYR. BUT HER SHAPELY FIGURE IS TALENT ENOUGH!

“SHE EARNS $10,000 A WEEK FOR HER DARING WEDDING NIGHT ROUTINE AT THE SWANKIEST NIGHTCLUBS IN LAS VEGAS, HOLLYWOOD, AND NEW YORK.”

She had toiled in dozens of heat-filled rooms. There were the clubs and the old burlesque houses with vermin crawling backstage—and not just the baggy pants comedians. Always the dust and the peeling paint and smell of beer and Limburger cheese, the comedians’ favorite.

She missed traveling. Like she had told Mike Wallace almost forty years earlier, she believed in UFOs. It was really quite arrogant to think humans were alone in the universe. How she wished a spaceship would swoop down and carry her away, which is what the drugs did. Her own unidentified flying opiate.

She was a dot. An infinitesimal insignificant blip in the universe. She could sense the junk moving through her. It made her heavy. Her breathing slowed. Floating. She was drowsy. She was coming down. The walls felt as if they were pushing in on her. Each breath an effort. She was pinned and had no escape.

She dozed. No memories, the reason she embraced the drug. Thoughts washed away and relief danced through her. No more pain. No more regret or shame. No more fear. All magically washed away. The crash was coming and would hurt. Stabbing sensation, vomiting, diarrhea. Until she injected herself again.

She woke with a parched throat. The skin loose and crepe-like around her neck. The once beautiful neck caressed by diamonds and pearls and expensive perfume and kisses from an endless variety of handsome suitors.

A cat mewed in the kitchen playing with the leaky faucet that she didn’t want the landlord to fix. It would mean he would have to come in and there would be too many questions. He would see too much. Needles, though she tried to be careful. But most of all she feared he would see her. Ten years she had been here. Before that the previous apartment had been miserable. One room and Lorenzo had brought too many of his friends in. The middle-class neighborhood had swirled with rumors because of the traffic in and out of their dark apartment on the narrow path crammed beside other cottages. Squalid, admittedly. A comedown in the world. From her big house to that. Thank God she had the prescience to put her name on a waiting list for this apartment. Most assuredly her last residence. Besides the neighbors’ parking right next to her window that disturbed her sleep and the sounds of the laundry room banging around the corner, she managed. Not enough privacy, but she could always make the best of whatever life threw at her.

She mustn’t let anyone see her.

She remembered how they used to steal the most appalling pictures of Garbo, head down, thick glasses, a black turtleneck pulled up to her chin, baggy pants and flat shoes walking the streets of Manhattan. The old sex symbol gone four years now. It didn’t seem possible. The steel-haired, flat-footed Swede captured trying to outwalk her past.

She had patterned herself after Garbo, seeking to emulate her allure, her mystery. She had been great friends with Garbo’s dear friend Virginia, yet she had never asked Virginia to introduce them. She, like Garbo, hid from the world. She had been so terribly insecure about her looks.

There would be no more adventures for her. She had lived her life in pursuit of adventure, getting everything out of life she could; fame, money, romance, sex, fun. She knew there were those that pitied the life she lived now. But they didn’t understand the life she had led. She had done everything she had wanted to do. And more. There were no more adventures in store for her, but she could remember the past ones.

She had been the stripper who had them lined up around the block in Chicago. Men had filled her hotels with flowers, showered her with jewels, furs; a few had punched her. She had lived her life in screaming headlines. And now this. A darkened room with thick red curtains, infused with dust. Old red curtains the color of the walls of her Canyon Drive bar. The curtains had come with her move; so little had.

She was the woman who created beautiful, memorable acts such as “Carmen,” “Afternoon of a Fawn,” “Chinese Virgin,” not to mention a dozen others. A “Salome” act that had gotten her thrown out of Montreal was now a yellowing photograph accompanying an article in a long-defunct girlie magazine. But she had been in them all. All the Confidentials and Gazettes and Night and Days .

That woman had filled her beautiful home with exquisite objets d’art. She had led a beautiful life. She had been a beauty. On the inside too. No one ever said a bad thing about her except to say she was “aloof.”

Where was Lorenzo? She vaguely recalled something about a hospital but couldn’t remember if he was in one or if she had been.

She heard Betty Rowland, the old bird, still bothered gluing false eyelashes on every day. She didn’t wear makeup any more. Hadn’t for years and years. She didn’t dress up, didn’t brush her hair that was as fragile as spun sugar from all the years of peroxide. Her vanity was long gone. Exhausted. She no longer spent hours in front of the mirror getting her “look” just right, oiling her hair and powdering her cheeks, inventing a fuller lip with red pencil, rubbing oil into her long legs, polishing her nails. Oh, the hours and years of attention she had lavished on herself. Now when she ventured out she threw on a worn long skirt, scarf, and hat. She had become like the women Colette wrote about in Chéri, “women past their prime, who abandon first their stays, then their hair-dye.”12

She remembered being a teenager and reading how to bleach hair in one of her movie magazines. Peroxide, ammonia, and Lux soap flakes. First she tried it on herself and then her sisters. No, Dardy hadn’t let her, until later. But Barbara had. And suddenly she and Barbara were platinum blondes. That turned a lot of heads. The boys had tripped over themselves to get to the sisters.

The silence in the apartment was eerie. Where were her “touches”?13 Her fans she corresponded with and whom she sent pictures of her younger self and they sent cash and kept her alive. If one of them would call, she would mention she could use a carton of cigarettes and some stationery. People had always done things for her.

A gnarled hand rubbed her perspiring forehead. It was sweltering. The breath in her head scratched at her brain. Years and years of smoking. She wondered if she would get cancer, hell, if she had cancer, if she would die from that. She didn’t want to go to doctors. Her body wasn’t worth preserving any longer.

She never had children. Her body was her temple. And a lot of others’.

Leaning toward the television next to her bed she turned it on and dozed, the noise filling her head with memories of a time she could understand.

Applause swelled. Always at the end of her act. No one had shouted, “Take it off! Take it off!” while she performed. Unlike the other strippers of her day, she commanded a certain amount of respect, just by the way she held herself as she stepped onstage. “You could hear a pin drop while I was on,” she said.14

One magazine noted, “With the audience now fretful in anticipation, Lili breaks the hushed atmosphere.”15

Another noted, “Lili is always the heroine in an exotic and sensual story. . . . Each guy can’t believe himself up there with her alone and so he’s silent, attentive, and respectful until the end of the story and the curtain brings him back to reality.”16

The applause had sustained her. She had lived off it. She had been an artist. She had always had to defend herself. Arrests, divorces, accusations in the papers. Questions regarding her “private parts,” testimony from “experts.” Countless humiliations.

As far back as 1948, after her first arrest, she had defended her performance as being art. To the judge she attempted to explain “anyone who doesn’t understand the story I dance probably would think the dance is suggestive. The story is about the lonely wife of a sultan who is unfaithful with a slave. My dance didn’t go that far, however.”17 Always she tried to inject humor in a situation. Her little acts always had a backstory, a beginning, middle, and end, she explained.

She took pride in her work. She was the first to produce little mini plays. “Pantomimes,” her great friend Tom Douglas had called them. She had changed the business of stripping forever. She had been the first stripteaser to play Vegas, for years. When Vegas had been a handful of quaint hotels scattered randomly in the middle of hot sand she had earned thousands there. A charming western town. Remote, outcast, trying to be something it wasn’t. Inventing itself.

She had been a star. She had worked hard to remain one. She learned where to place a light, what color gel to put over that light. She didn’t skimp on her costumes, one of a kind from Bergdorf Goodman, and jewels from Cartier. She created elaborate sets decorated with antiques. She gave everything of herself on the stage. Ironically, reviewers said her popularity was due to the fact that she was unattainable. “She had this wonderful haughtiness. After she’d taken a few things off, she’d half cover herself with the curtain and say, ‘That’s it, boys. You’re not getting any more from me.’”18

She didn’t play to the audience as the majority of strippers did. She danced as if she were alone. Reporters were wrong. She gave everything. She was a savvy, calculating entertainer. She knew who could help her and what the audience wanted. She regularly decried any sense of ambition, saying she preferred to stay at home, that she worked only for the money. She always “needed” it, true, but she lived and breathed her work. It is what would kept her alive and on top. It was the only thing that made her feel substantial, the only thing that meant something.

There weren’t many regrets. She had lived her life as she wanted to. Yes, she had lost her house, her looks, her health, and her family. She had nothing. But she had had it all. Every single damn thing. The men had come to see her because they wanted her. The women came because they wanted to be like her.

When her act ended and the audience applauded, she smiled, satisfied, and slipped between the curtains and off the stage. The show was over. And Lili St. Cyr would vanish.