Читать книгу Goddess of Love Incarnate - Leslie Zemeckis - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TEN

The girls never feared misbehaving at the nightclub because Alice had sternly instructed them on how to behave. She told the girls to not do anything they couldn’t tell her about.144

Idella, who once had her own aspirations for the stage, sidetracked either by polio or children, perhaps tried to dissuade the girls from mingling with other showgirls, because Lili did not make friends. Maybe it was part of the conflict she felt about the career. Dardy later would complain about the strippers and burlesque performers, “They weren’t necessarily the people you wanted to hang out with.”145 Other chorus girls couldn’t help Lili’s career, so she would feel no need to make friends with any of them. By now she had taken a small apartment in Hollywood and was enjoying her space and privacy away from Idella’s nagging and Alice’s worry.

EVERY NIGHT LILI WALTZED INTO THE NIGHTCLUB, PAST A SWEEPING staircase winding up to the second floor. She would stroll past the bar looking for Dick to say hello. In a short time the place was packed with mink-clad women in jewels, men in tuxedos. Everyone was laughing, drinking champagne, and watching a terrific night of entertainment.

Errol Flynn and John Barrymore were regulars. Lana Turner was spotted wearing a dress of beige crepe and a white fox. Texan Rex St. Cyr impressed Lili, sweeping in regularly with Lady Furness (the former Thelma Morgan), the Prince of Wales’s former paramour before her friend Wallis Simpson stole him. Furness’s identical twin, Gloria Vanderbilt (mother of fashion designer Gloria Vanderbilt), clung to St. Cyr’s other arm. He threw $100 bills around as if they were confetti.

The self-styled Texan had been born Jack Thomas. He was a generous supporter of the Hollywood Canteen and made sure his name was in the entertainment trades lauded for his efforts. St. Cyr hosted numerous parties attended by celebrities, despite the fact that no one knew exactly who he was. When hosting the 13th Academy Awards, Bob Hope opened his monologue with, “Who is Rex St. Cyr?”146

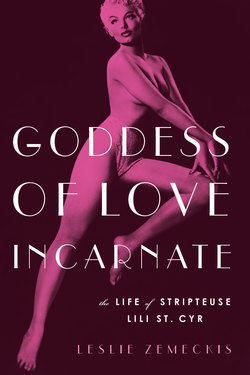

Lili at the Florentine; Barbara is in the background

In June of 1942, St. Cyr’s name was important enough to be included as one of the guests at Errol Flynn’s birthday party (which got out of hand when a butler was injured) along with Jack Warner, Ava Gardner, Tyrone Power, and Dinah Shore.

Lili was fascinated by him. His name would stay tucked in her head, associated with grandeur, flamboyance, and wealth; it sounded French and Lili loved all things French. She admired—and later emulated—anyone who was generous, mysterious, and glamorous.

Barbara’s sometime beau was the tall and handsome Hearst columnist Harry Crocker who invited her swimming at San Simeon. As a regular part of the newspaper magnate’s circle (he had done a film with Hearst’s mistress Marion Davies, Tillie the Toiler, in 1927), Crocker had a distinguished pedigree. His father was an oil tycoon, his grandfather a railroad builder, and his uncle an important banker in San Francisco.

Crocker snapped a picture of Barbara in the San Simeon Grecian pool and inscribed it to Idella.

Barbara at San Simeon—Inscribed by Harry Crocker “For the nicest mother in the world”

BARBARA ALSO HAD DATES WITH THE FRENCH-SOUNDING FRANCHOT Tone, who in reality had been born in New York as Stanislaus Pascal Franchot Tone. The thirty-five-year-old movie star would send his limousine to wait for Barbara at the Florentine’s artists’ entrance and drive her back to his house in Beverly Hills for dinner. If Lili didn’t have plans, she would show up too. All three would sit at one end, “dwarfed by the table.” He was a good sport and would have his uniformed houseman serve the hungry girls a sumptuous meal under a chandelier lit with candles.

He had a large English-style home, with formal dining room as “big as a ship” that looked out on beautiful gardens, the windows swathed in sheer lace curtains.147 Tone’s butler would serve lavish seven-course meals. The sisters could eat; they weren’t dainty, nor did they pick at their dishes, despite being rail thin. Franchot would tell the butler to call the driver and made sure the sisters were returned to the Florentine in plenty of time so as not to miss the next show. He didn’t want them fired on account of him.

One night a handsome, round-faced actor with a deeply dramatic way of pontificating asked the twenty-four-year-old Lili out.

His name was Orson Welles, theatre director, actor, and current Hollywood boy wonder, hot off his controversial production of War of the Worlds that for a short time sent radio waves of panic across America with his faux invasion of aliens taking over the earth. Hollywood came calling with a contract offering him almost (this would later be debated) complete artistic control. Welles was fully enamored of himself and his enormous talents.

Backstage at the Florentine, Granny interrupted Lili. He watched her dip a damp cloth in a jar of Ponds and rub it over her face to remove the heavy pancake. Other girls in the crowded dressing room were doing the same.

“Someone wants to meet Miss Champagne. Hurry up. I’ll wait to introduce you.”148

Granny had nicknamed Lili because of all the bottles purchased on her behalf.

Lili favored masculine-looking pants and button-down shirts offstage and slipped into a pantsuit. Granny complained, “Why do you wear that, Lili?” And he left her to finish getting dressed.

Dressed, Lili entered the front of the club and found Granny waiting for her. He led her to a small table.

“Marie, this is Mr. Orson Welles,” Granny said, wearing a satisfied grin on his face. The place was packed and even among the many celebrities all eyes turned to Welles’s table where the striking dancer stood in her very unshowgirl-like outfit.

Welles stood and took her hand. “Pleased,” he said in his deep-timbered voice and bowed. He was conservatively dressed in a dark suit and tie. His voice was distinctive, but Lili thought it “domineering.” “Join me?”

Lili, knowing he was the “important man of the year,” slid into the banquette.

“Champagne?” he asked.

Welles poured a bottle of Piper-Heidsieck that sat in a silver ice bucket at his table.

“Mr. Welles—”

“Orson.”

In the middle of the table was a small vase of fresh flowers. He plucked a rose from the arrangement and put it in his buttonhole. Then he did the same for her.

They made idle chatter but didn’t stay long, not even to finish the bottle.

“Do you drive?” Orson asked.

She smiled sheepishly. “I do . . . but not well,” she admitted. Driving made her nervous. She found it a difficult task and had a hard time concentrating behind the wheel.

Orson stood up. Lili stood nearly as tall as the director. They were two distinct figures as they strolled arm and arm across the crowded club and out the front doors. Lili could feel jealous eyes boring into her, which made her stand even taller, basking in the glow of envy. It was a different kind of attention, and one she didn’t mind. She had stopped caring that women sent daggers her way. Recognition of any kind was paramount for Lili.

Lili and her first car

Welles slid into the big Pontiac that another admirer of Lili’s had lent her. It was a beautiful black convertible, big enough for her to feel safe behind the wheel. Lili took the steering wheel in hand.

WELLES WANTED TO TAKE HER “SOME PLACE SPECIAL” AND INSTRUCTED her to head east on Sunset Boulevard, then west toward Watts, south of downtown, which was at the time only just becoming a predominantly black neighborhood.149

Lili nervously parked on what she thought was a rather dodgy street, hoping nothing would happen to her borrowed car.

They got out of the convertible and walked to a nondescript one-story building. Welles knocked on the door.

The door opened a crack and a man’s narrow face poked out. There was an exchange Lili didn’t hear but immediately the door was hinged open.

It was a big room, grand, yet dark, with many tables filled with laughing and drinking couples and heat. There was a tiny stage with a black pianist playing jazz. They were ushered to a table near the piano. The black man acknowledged Orson and continued playing with a big grin on his face.

Interestingly, Lili’s fifth husband, Ted Jordan, would make note of a “Brothers Club” that Orson liked to go to about this time, which was surely the same club he took Lili to. One knocked on the door and a “mean-looking man glared at you through a porthole” until you said the password, “Brother, let me in.”150

To Orson the place was hip. They ordered sloe gins. Orson ordered BBQ chicken and ribs. They didn’t speak much, just listened to the loud music as it filled the room. Orson liked it more than Lili. But she was enjoying herself. Jazz would never be her favorite music nor places like this her thing. Still she loved the illicit feeling of it, the hipsters in their bright clothes. Hepcats. The men wore shiny high-waisted, tight-cuffed zoot suits, pinstriped or brightly colored. Others wore shiny tuxedos with opera scarves trailing off them. Watches dangled on chains down to baggy-panted knees.

It was nearly 4 a.m. when Lili dropped Orson at the Garden of Allah, the hotel where he was staying at the corner of Sunset Boulevard and Crescent Heights. He chastely kissed her goodnight.

“Tomorrow?”151

They agreed and she drove to her tiny apartment in Hollywood. Still not tired, she undressed, washed her face, and leaned her head against the window sill looking down on the side of the opulent Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. A cool breeze lifted her hair.

The next night she met Orson at his hotel. He had been renting an apartment at the former residence of silent-screen actress Alla Nazimova. And, in fact, he’d broadcast several live episodes of his radio series Campbell Playhouse from the Garden of Allah.

The Allah was the place where a multitude of celebrities found refuge, both short-term and long. Writer F. Scott Fitzgerald lived there, as would Dietrich, Garbo, and writer Robert Benchley. There was the main hotel, Nazimova’s former mansion, with twenty-five individual villas built around the three and a half acres of gardens. It was Spanish Moorish and exotic like the former actress herself. There was a central pool where many recovered from hangovers. The parties flowed endlessly. It was charmingly decadent, just what Lili approved of.

Lili thought the setting incredibly romantic and ideal for a rendezvous.

For the next week she would drive to the Garden after her show or meet Orson at the Florentine and they would go together for a late dinner at any of the illegal bars in Watts that he loved. Orson seemed to know them all. One night her tires were slashed outside a club while they drank inside. He offered to pay for new ones. They would end their nights in the early-morning hours at his bungalow listening to the sounds of others partying nearby.

One morning when she woke, it was early afternoon and she discovered a note on the pillow next to her. “I am at the pool.”152

She put on her sunglasses and the pair of shorts she had brought and wound her way over to the pool where she was surprised to see Orson in a sport coat and open shirt, scripts scattered about, surrounded by a bevy of sycophants hanging on to the his every order. She thought he acted like a king.

She stretched out on a lounge in the sun. He made sure one of the hotel’s staff brought her a steaming cup of coffee, which she savored as she watched him, amused by how his minions fluttered nervously, worshipfully around him.

Orson had a two-picture deal at RKO and acted like royalty, a script in his hand and one at his feet. A cigarette was lit, and he constantly ran a hand through his hair.

A young secretary was taking notes. He was planning his next film, what would become the now classic Citizen Kane.

Tired and bored, Lili fell asleep. She was rarely impressed with the stature of others, much preferring to have attention center on herself.

One weekend Lili decided to stay out in Eagle Rock and asked Orson to catch a ride out to fetch her. This way he could meet Alice and the rest of the family.

He arrived at Bedlam Manor, hat in hand, carrying a large wooden staff, something Moses might have shook at the heavens, and wearing a wool burnoose. There was even a hooded cloak dramatically thrown across his wide shoulders. He claimed to be preparing for a part.

Dardy and Barbara couldn’t help but giggle.

The entire family gathered around to listen to him pontificate about New York and the film he was writing. A film that was going to change movies forever. As he talked, the women sized him up. True, he was a movie star, but he sure liked to go on about himself. This was a houseful of women who each thought they were the center of life.

Lili kept her date waiting while she curled her hair, applied makeup, and dressed meticulously. The family’s eyes started glazing over as Orson kept talking, not allowing anyone to get a word in.

They were grateful when Lili finally descend the staircase. She towered over most people, except her sisters and Orson. The director with his thinning hairline, which he was most sensitive about, appreciated Lili’s fine beauty and her statuesque figure.

She smiled and Orson dramatically rose; bowing formally, he took her arm. She was amused. Out into the night they went. It would be one of their last dates. He was too wrapped up in himself for her taste. His preoccupation frustrated her.

Dardy raced over to the chair Orson had sat in, intending to mimic the “great” actor stooping down into his throne.

“Stop,” Alice shouted, raising up her hand. “Don’t sit in that chair. His royal ass sat there.” Everyone burst out laughing.153

Lili felt lost around Welles. He took up so much air. She compared him to Napoleon. He never listened to her, his mind clearly elsewhere. Lili was equally frustrated at work. She was trying to figure out how to get out of the Florentine. She felt as if she were playing a game waiting for a career to take off. She was unhappy and bored. Her nerves were on edge.

Another reason she didn’t care for Orson was he was a cheapskate. He ordered the least expensive thing on the menu, never asked if she’d like a second drink, and tipped horribly. Lili, who never had money, was free with hers. She bought endless gifts for her siblings and Alice. Like her grandmother, Lili couldn’t stand to see someone in dire straits. A lot of the girls at the club, though they weren’t close with Lili, were always asking for small loans. She would lend a few bucks if a girl needed it. After all, it was only money. She could always make more (though she complained regularly how she barely had enough to spend going out to a club).

THE DAYS TURNED WARM AS SUMMER APPROACHED. LILI AT LONG LAST started an overdue romance with Dick Hubert, the handsome headwaiter at the Florentine. Hubert must have seen her sweep by on the arms of Orson and other attentive males.

Despite the fact that she was enormously popular at the club with customers who asked after her and came back often, or cheered enthusiastically, Lili knew she wasn’t any closer to being a headliner. She was just one of a dozen. In Dick’s eyes she stood out.

Both sisters were getting mentioned in the gossip columns, even if their names were usually spelled incorrectly. Men bought presents, drinks, and flowers.

Lili would claim Dick asked her to marry him on their second date, though surely they had known each other for months.

She was “lonely” and agreed, eager to set up house with someone who adored her. True, they really didn’t know each other but she liked having a man to take care of. It made her feel complete. She would dote on Dick, buy him things, attempt to cook. She vowed to be a wonderful wife and sex partner. And Dick already knew about her work; he wasn’t likely to make her quit as Cordy had. It seemed an ideal arrangement. She had developed a cavalier philosophy when it came to marriage; if it didn’t work, there was always divorce.

Lili and second husband Dick Hubert

LITTLE IS KNOWN ABOUT DICK HUBERT OR WHERE LILI AND HE LIVED. Billboard listed him as the headwaiter through early 1942 when he became the maître d’ after his divorce from Lili.154

They drove the three hours to Tijuana and were married. “In those days you had to wait three days in California,” Dardy said about the popular Mexican weddings both she and Lili enjoyed. “Tijuana was easy.”

Dick, a beautiful dresser, spent hours grooming. He wore tails to work, bought Lili a fur, and drank “a lot,” a turnoff for Lili, which lead to arguments, which she didn’t care for.155 They spent days sleeping and nights separated by a stage. No doubt Dick drove Lili to the club every late afternoon. She had never liked driving, and besides, Lili liked being driven. She liked having things done for her. It was a habit that would become an expectation that people would drop whatever else they were doing to attend to her.

“We were strangers who slept together,” Lili later explained.156 She would admit it should have been a weekend love affair, but in those days—and she would claim this into the 1950s—women didn’t shack up. They got married. And Lili was no different. It is what Alice had taught her. Lili would always want the fireworks and drama and passion of a courtship. But she did not like the routine of marriage. Dick asked at the opportune time, when she was “waiting for men, waiting for a career.”157

A source of friction must have been the fact they had to keep the marriage a secret. Granny would expect her to continue to sit at customers’ tables. Perhaps Dick became jealous, as so many of her husbands would. Maybe he scoffed at her ambition to be a headliner. Either way, Lili was too young to settle down for long. With Dick she began a lifelong habit of leaving someone midsentence if she didn’t like what they were talking about or if she grew bored. She didn’t apologize, never realizing—or caring—how rude it was. She gave the impression they had offended her. She would simply get up and leave. No explanation. It was what she would do with this marriage.

ONE NIGHT LILI OVERHEARD DINGBAT AND A FEW GIRLS CHATTING after the show about how a couple of big producers had caught the performance.

Lili would learn Lou Walters was an important director, producer, and owner of the Latin Quarter Club in Miami. Eventually he would have a string of clubs in New York and Boston. It was the top of the top spots to play.

A child of a Polish Jewish refugee, Louis Walters was, despite being unattractive with a glass eye, “dapper, slim,” and a man who spoke in slogans with a British accent, having been born in London. One of his catchphrases was “Never get a suntan that leaves lines.”158

Lili would take it to heart. Another was never get fat and to always do your best even if it was just a rehearsal.159

Walters had caught the show along with talent agent Miles Ingalls, who booked burlesque comedians and dancers. He maintained offices in the Astor Hotel in New York.

Lili found out the high-powered duo were staying at the Roosevelt Hotel on Hollywood Boulevard.

Lili grabbed some of the publicity photos she had recently shot with John Reed, the big photographer on Hollywood Boulevard with the gigantic picture of Dietrich hanging in the window. She wrote a note on the pictures and stuck them in an envelope.

Lili made her way to the Roosevelt, a twelve-story Spanish-style hotel financed partially by Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, which stood across the street from the massive Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. The hotel had opened in the twenties and was frequented by a slew of movie stars. It was the epitome of glamour.

Inside the beautiful lobby were big potted palms; the walls were painted a muted yellow. At the front desk she told the receptionist she had a package to deliver to Mr. Ingalls. The receptionist told her the room. Lili sprinted toward the staircase. She was claustrophobic and avoided elevators when she could.

She slid her envelope under the agent’s door.

The next day the phone rang. It was Ingalls looking for Marie Van Schaack.

He would have remembered Lili from the lineup and the club’s brochure. He asked her if she wanted to dance in the Latin Quarter in Miami. He had already showed the owner—Walters—her picture and he offered to book her.

Of course Lili agreed. Miles told her it would be a while before she would start and in the meantime she should get all the experience she could.

Lili told her husband she was quitting the Florentine, moving out, and divorcing him. She wanted to “be discreet” in the way she left both her “elegant husband” and the Florentine, which she considered “her second home.”160 She would tell no one about Miles Ingalls.

Was Dick surprised? When Lili turned off to someone it was obvious and uncomfortable. Maybe he thought his wife sheltered, too immature, a pretty young girl looking for a bigger fish that could make her career. All things that were true. Hubert didn’t fight her decision and that was the end of marriage number two.

Lili made a clean break. She headed for the cool air of San Francisco.

Lili at the Florentine—easy to see what Miles Ingalls saw