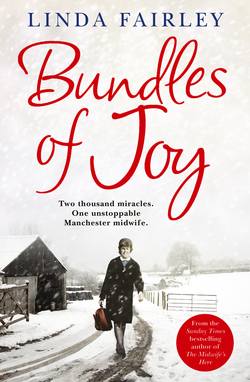

Читать книгу Bundles of Joy: Two Thousand Miracles. One Unstoppable Manchester Midwife - Linda Fairley - Страница 11

ОглавлениеChapter Three

‘W-w-what did I do wrong?’

‘I have some news, I think,’ I told Graham one morning.

He raised an eyebrow and looked up from his cornflakes to see me standing there in my uniform with both hands laid gently on my belly.

‘I think this is it. I think I’m pregnant!’

Graham’s face shone instantly. He could not have looked happier if he tried, and he asked me a string of questions about when we would know for sure, how many weeks I might be and when the baby would arrive.

It was June 1973 and Graham and I had been trying for our own baby for several months. I had been a sister for more than twelve months, which was an achievement I had wanted to get under my belt before having a baby of my own. Everything was just as I’d planned.

‘Has your job ever put you off having your own children?’ my old friend Sue Smith had asked me one night when we were catching up on the telephone.

She worked as a schoolteacher in South Wales now and had a baby daughter called Miranda, and I think my reply was something along the lines of, ‘I suppose I could ask you the same thing!’

It was a fair question from Sue, I suppose, and one that I’d been asked several times before in recent years. Never once did I take it very seriously, though. The fact that I’d seen some very sad outcomes, not to mention having witnessed women suffering terribly in labour, never put me off wanting to have children of my own.

It was very unusual for things to go badly wrong, and when Graham and I had made the decision to start a family I was filled with nothing but optimism and hope about becoming a mum. In fact, I thought nothing could go wrong for me at all, which may seem a little unbelievable, but it was true. The hundreds of joyful births, the wonderful, heart-warming deliveries I’d been a part of and the love-filled faces of the new mums – that was what I thought of, and that was what I envisaged for myself.

When I suspected that I actually was pregnant, I could not have felt happier.

‘The GP will have to send a urine sample off for testing,’ I told Graham. ‘I’ll make an appointment today. Then it could take a week or so to get the result.’

‘A week or so? Couldn’t you find out sooner, through work?’

‘I’ll try,’ I replied. ‘Leave it with me.’

You couldn’t just buy pregnancy kits at the chemist in those days, and we midwives inevitably saw it as a perk of the job to be able to use our skills to help each other out. I was back on the labour ward with Judith Houghton at this time, and I waited until I had the chance to take her to one side.

‘I think I’m pregnant,’ I whispered excitedly. ‘Would you have a little listen for me?’

‘Of course! How wonderful, Linda,’ she replied. ‘We could nip off and do it now if you like. Let me get hold of a monitor.’

We entered an empty side room where Judith listened to my abdomen using a hand-held foetal heartbeat monitor called a Sonicaid. These were quite new to the hospital and were in fairly short supply, and the early models were a little temperamental to operate. This meant the old-fashioned Pinard’s stethoscope was still more commonly used, and we typically only used a Sonicaid on patients who had experienced a bleed or gone into premature labour. However, amongst ourselves it was viewed as quite an exciting perk of the job to use the Sonicaid on each other.

‘I think these things are wonderful,’ Judith commented as I lay on the bed and unbuttoned the front of my dress while she swiftly switched on the monitor. She slid the head of the plastic device over some jelly applied to my tummy, and moments later the Sonicaid’s ultrasound waves picked up a heartbeat. We both squealed excitedly.

‘I think your diagnosis may be correct,’ Judith said giving me a hug ‘Congratulations, Linda.’

I knew that the Sonicaid generally only picked up a heartbeat from ten weeks, or more likely twelve, which tied in with my dates. I would have to wait for a referral from my GP, of course, before I could book myself into the antenatal clinic and announce the good news publicly, but in that moment I had a very good idea that if my calculations were correct, by January 1974 I would be a mum, and I was thrilled to bits.

Looking around the labour ward later that same day, I had a sense of feeling slightly more connected to the women than I ever had before. I saw them as kindred spirits as well as patients now, and I looked forward to being able to confide in my patients, and tell them that I too had a new life inside me. I was having a baby, just like them.

‘I hope you’ll set a good example,’ Judith teased when we went on a tea break later. I’d told her I wanted to have my baby here at the maternity unit, as I knew I would be well looked after and would feel comfortable in such familiar surroundings. It never entered my head to go anywhere else, in fact. Why would it?

I also hoped very much that Judith might be able to deliver me, although I knew very well that you could never be certain who your midwife would be, not just because of shift patterns but because of the uncertainty of delivering on your due date.

‘I’ll be a model patient, I promise!’ I laughed. ‘Can you really imagine me hollering like some of the ladies we see on the ward?’

‘No!’ Judith retorted. ‘I don’t suppose I can, but you never know!’

Several weeks later, after my pregnancy had been officially confirmed by my GP, I attended my first antenatal appointment. Graham was even more excited than I was about the baby, if that were possible, and offered to take time off work to come with me. It was still very uncommon for men to come into the clinic, however. Also, my colleagues were very good to me and always slotted me in when I was on duty and could pop in during a break.

‘There’s really no need to come,’ I told Graham. ‘I’m perfectly fine on my own. You stay at work, you’ve got a lot on.’

‘Whatever you say, Linda,’ he replied. ‘You’re the expert here.’

Graham’s vending supplies business was doing well, and he and his brother had expanded it and moved into new premises. It was lovely that he wanted to support me every step of the way, but we both knew there was really no necessity, and the business needed him more than I did.

I’d grown up an awful lot in the time I had known Graham. Gone were the days when I relied on him to hold my hand and dry my tears after a tough day, as he did so many times when I was a teenager during my training at the MRI. I was a much more independent person now and, of course, when it came to having babies I was indeed the expert.

I asked if I could have Dr Bedford as my consultant as I had always admired his skills and his extremely pleasant bedside manner. My ‘booking in’ appointment was completely routine. I had no problems to report, and Valerie, the midwife in the clinic, listened to the baby’s heartbeat with the Sonicaid, which of course was so lovely to hear again. She also confirmed what I had already worked out myself, that my due date was 7 January 1974. It felt a little odd sitting on the other side of the desk, but it wasn’t unusual for midwives who worked at Ashton to have their babies in the maternity unit, and I felt at ease.

I returned to the labour ward feeling on top of the world, and looking forward to sharing my exciting news with all of my colleagues. However, I was dismayed to discover something of a staff meeting going on in a side room, where several midwives were assembled with Sister Margaret Penman, who was looking very serious.

‘Do come and join us, Sister Buckley,’ she called when she spotted me. ‘We’re just discussing the supplies being ordered on the night shift. You may have something to add.’

I walked in to hear Sister Penman, who was the senior sister on the labour ward, explaining very seriously that an unprecedented amount of flour, bicarbonate of soda and butter had been ordered for the labour ward kitchen.

‘As you all know, I’m a very reasonable sister,’ she said, which prompted nods of agreement from most of us gathered. ‘I’m certainly not one to nit-pick about an extra pint of milk for your teas and coffees and the like. But if I don’t get to the bottom of this I will have Miss Sefton asking questions, and we certainly don’t want that, do we?’

An emphatic ‘no’ came from every person’s lips.

‘So please can somebody explain to me what is going on?’

Sister Penman knew that most of us midwives worked night shifts as well as days, and would no doubt be able to solve this great bicarbonate of soda mystery without the need for further intervention from Miss Sefton.

As the rest of us gave each other sideways glances, deciding who was going to spill the beans, one of the new pupil midwives bravely stepped forward.

‘Sister Mallon makes pancakes for us on nights sometimes,’ little Annie said, blushing. ‘They’re delicious, and we give them to the patients, too, if they want them. It’s our fault, we’re always asking her to make them.’

Sister Penman rolled her eyes. ‘I honestly don’t know how you find the time to be fiddle-faddling about with such things,’ she chastised. ‘Please don’t encourage Sister Mallon any more. I have it on good authority that she’s an impressive cook, but I think we must let her practise her skills at home from now on. I will have a word with her.’

We were all dismissed forthwith, stifling laughter as we thought about how our eyes twinkled when the overnight order sheet arrived and we all looked down the list and said, ‘Oooh, let’s have some of that!’ or ‘What shall we make next?’

It wasn’t just kitchen supplies that we used a little lavishly. Since the move to the new unit and the shift to disposable equipment over the last few years, most of the staff had got into the habit of being really quite wasteful. It was such a revelation to us to have boxes of pre-sterilised needles and razors on hand, not to mention paper hats and plastic aprons, that we took full advantage. Even the bedpans were disposable now, made of a rigid grey card that could be dumped in a ‘bedpan masher’ – complete with their contents, thank goodness. Needless to say, nobody missed the old days of having to empty out the metal pans and wash them in the steriliser.

We were quite oblivious to the effect all the extra waste might have on the environment, and when it came to the plastics, recycling was not a word we were familiar with. Greenpeace was a fledgling organisation at this time, and I was vaguely aware of its anti-nuclear protests in Vancouver in the early Seventies, but to be honest I didn’t make any connection between polluting the world with nuclear bombs and creating piles of NHS waste. I don’t think I was alone in this ignorance, either. Midwives generally enjoyed the luxury of it all, knowing that the next box of shiny new supplies was only a tick on an order slip away, and rejoicing in the fact we no longer had to endure the smell of washing out metal bedpans.

If we ever did think twice about our actions, the extreme busyness of the wards gave us a good excuse for being profligate. On a typical day shift we had up to fifteen ladies arriving on the labour ward, and usually on nights five midwives would deliver two or three babies each, making us very grateful indeed to have such plentiful supplies so readily available.

On one such hectic shift, on a warm day in July 1973, I was dispatched to look after a new arrival on the labour ward. My patient was a rotund, jolly-looking lady called Rosemary Battersby. I will never forget her for many reasons, and she was actually the very first patient I confided in about my own pregnancy.

Examining Rosemary in the admissions room, I was surprised to see her labour was so well established that she really should have gone straight into a delivery room, but at that time there was a strict process we midwives were instructed to follow. All new arrivals were seen first in the admissions room, where many were still shaved and given an enema, provided labour was indeed established and they were already at least three centimetres dilated. Next, the women were taken to a first-stage room, where they laboured until they reached about nine to ten centimetres. Finally, when they were very nearly ready to push the baby out, they went into a delivery room.

Looking back it wasn’t a good system, as it meant we were often shifting ladies between rooms when they were in the advanced stages of labour and could barely walk, let alone get on and off trolleys and beds. It was certainly not unusual to see women actually pushing as they were wheeled along corridors.

‘My goodness, you’ve done a remarkable job all by yourself,’ I said to Rosemary, seeing that she was already an impressive nine centimetres dilated.

‘To be honest, I tried to put off comin’ in until after the tennis,’ she told me.

I knew Wimbledon was on, and there had been great excitement as it was the first time the women’s final had been between two Americans, Billie Jean King and Chris Evert. I’m not a big tennis fan, though, and I hadn’t really been following it.

‘Well, I’m glad you’re here now,’ I told her.

When I felt Rosemary’s huge abdomen, her contractions were frequent and strong, though she didn’t appear to be suffering too much and even managed to give me a wide smile. I told her I was going to by-pass the first-stage room and take her straight to a delivery room as her labour was advancing so well, and I remarked that she appeared very good at dealing with the pain.

‘I used to be a dancer,’ she said proudly. ‘Did the summer season at Blackpool for eight years running. My Billy reckons I must still have muscles of steel, under all this blubber!’

She let out a raucous laugh as she patted her tummy, and I laughed, too. This was her first baby, and I had a feeling I was going to really enjoy this birth.

‘That’s ’im there,’ she said, nodding down the corridor as I helped her waddle carefully into a delivery room.

Billy was sitting on a plastic chair, his nose buried in a Manchester Evening News. ‘’Ere, Billy, wish me luck!’ Rosemary called over, making him bounce up as if his seat had turned into a trampoline. He was a well-padded man with ruddy cheeks, a small goatee beard and long, straggly hair. I noticed he was wearing a purple jacket and wide-collared chocolate brown shirt, which made him look somewhat bohemian compared with most men I was used to seeing in Ashton.

Billy bounded up to us, looking a tad unbalanced in a pair of camel brown platform boots, and asked animatedly whether it was ‘show time’.

‘Nearly!’ Rosemary chuckled. ‘Midwife here says I’m ready to go straight into the labour room!’

Billy planted a noisy kiss on his wife’s forehead and told her, ‘Break a leg now, Rosie!’

‘Is your husband in the entertainment business, too?’ I asked once we’d got Rosemary into a hospital gown and she was lying down fairly comfortably, a foetal heart monitor strapped across her expansive belly.

‘Oh yes,’ she nodded.

Rosemary was huffing and puffing now, the effort of heaving herself onto the delivery bed seemingly giving her more grief than the labour pains themselves. Nevertheless, she was determined to tell me all about her Billy.

‘He was a Redcoat at Butlins at Skegness before I knew him,’ she panted. ‘And we met when he joined a band and – uuuurggghhhh, that were a nasty one – did the summer season at Blackpoooowl. Ow, owww, owwwww! Is it meant to be hurting so much? I were fine a minute ago. He plays the ukulele like a dream.’

With that she let out a few rather musical notes of her own as the strength of her contractions intensified again and again, and yet again.

‘I must be mad! Why am I doing this?’ she wailed flamboyantly at one point, but I could tell she was simply letting off steam and was actually coping really well. Rosemary was clearly very comfortable taking centre stage, and even at the peak of labour she couldn’t help holding forth.

‘You … urgh – you got any yerself, Nurse?’ she asked me at one point, quite unexpectedly. ‘Babies, I mean?’

‘No … but I’m just over three months pregnant!’ I blurted out, astonishing myself momentarily with my revelation.

Rosemary’s face lit up, and I felt a real connection to her.

‘Good luck, nuuurrgghhhhsseee! Sorry – sorry – sorry – I want to pu-pu-puuusssshhhhhh!’

It was less than fifteen minutes since we’d got her into this room, and no more than an hour since her arrival at the hospital, but I could see Rosemary was ready.

‘OK, OK,’ I said. ‘Wait until I tell you, wait a bit, wait a bit, big breath – go now!’

Rosemary gave a substantial push and I could see the baby’s head, advancing, just as I wanted it to.

‘All right?’ she puffed as she gasped for air.

‘Brilliant,’ I said. ‘Magnificent!’

I wanted this wonderful performance to conclude well. Rosemary’s sunny disposition had rubbed off on me, and I was enjoying this birth a great deal.

‘I need the same again, when I tell you … OK, OK, go again, keep going …!’

An almighty cry filled the entire room moments later, heralding the arrival of a very rosy-faced, bright-eyed baby girl who landed with a little bump on the bed. Scooping her up, my eyes immediately fell on the baby’s left arm. Instinctively, I reached for a cotton towel and draped it over the baby, leaving only her pretty little face peeping out.

I was very upset by what I’d seen. At the end of the baby’s left arm there was no hand. It was just a little stump, with a tiny bud of a thumb and no fingers. Rosemary was propped up on her elbows now, her eyes darting between her large deflated stomach and the baby in my arms. She seemed stunned into silence by the speed of the delivery, which had left her dragging in breath noisily. She could not have seen her daughter’s arm; I had covered her up so quickly I was sure Rosemary hadn’t seen what I had. It was down to me to break the news.

‘Congratulations Rosemary,’ I smiled warmly. ‘You have a lovely baby daughter.’

I remembered hearing of a scenario like this during my training, when I was out in the community with Mrs Tattersall. She had told me how one of her colleagues delivered a breech baby who had a deformed foot. It was a difficult situation because the baby’s legs were delivered first and so the community midwife knew many minutes before the baby was even born that there was a problem. I fast-forwarded in my mind to what Mrs Tattersall’s answer had been when I asked her how you should deal with such a case.

‘Let mum see the baby and look at the baby,’ I heard Mrs Tattersall’s raspy voice say. ‘If she doesn’t remark on the deformity herself, you need to refer to it gently, in a very nice manner, of course. “Unfortunately, your baby’s foot is a little deformed,” you should say. “But there are things you and he can use to help, and I’m sure he will cope well …”’

I cut the cord and delivered the placenta as Rosemary lay back, quiet with exhaustion. ‘Is she all right?’ she asked softly. ‘Can I see her?’

The baby was wrapped snugly in a blanket now. I lifted her over, letting Rosemary feast her eyes on her daughter’s beautiful face for a moment before I loosened the cover. The little girl cried when the air hit her bare chest. Her legs wriggled and she shot both arms up in a reflex action, just as a newborn should.

Rosemary’s eyes fell on her daughter’s arm, and I was very comforted by the fact I could still hear Mrs Tattersall guiding me.

‘Wh-wh-what’s happened to her hand?’ Rosemary asked slowly. ‘Is it my ff-fault?’ Tears were welling in her eyes. ‘W-w-what did I do wrong?’

‘You did absolutely nothing wrong at all,’ I replied, handing her the snuffling baby to cuddle. ‘It is just one of those things. I’m sure you must know other children who were born with little things not quite right. It happens, but I’m sure she’ll cope really well.’

‘Poor little soul,’ Rosemary said, giving the little girl a gentle kiss on the forehead.

I swear Mrs Tattersall dug her bony elbow into my rib at that precise moment, prompting me to add, ‘If you look, she’s got this little bud here in place of a thumb, which is good. It will help her to grip things.’ The words came out of my mouth, but they had been planted firmly in my head by Mrs Tattersall, and I silently thanked her.

When Rosemary indicated she was ready to see her husband, I asked Billy to step inside and meet his new baby daughter. I could see they were a solid, close couple and I would let Rosemary tell him the news in her own way and in her own good time. I would stay close by, busying myself with writing up the notes and tidying up, so as not to intrude but to be there if they needed me.

What happened next was incredibly heart-warming. Unbeknown to me, Billy had brought his ukulele into the maternity unit. It seemed he had planned all along to serenade his wife and new child, and this unfortunate turn of events had not dented his enthusiasm.

‘I would have waited a bit, you know, if things …’ he explained to me as he took the instrument slowly from its case. ‘But … can I?’

I nodded and made sure the door was shut behind us, and then I watched and listened, spellbound, as Billy gently strummed his ukulele and gave a brief rendition of ‘All You Need is Love.’

Rosemary rocked the baby in her arms and sobbed quietly before saying, ‘Come ’ere, ya soppy old devil!’

Billy put his arms around both his wife and new baby daughter, and I knew in that moment that what Mrs Tattersall had said to me many times was so true. ‘People cope, you’d be surprised Linda. There are always ways around things. It usually works out in the end.’ These were all typical Mrs Tattersall sayings, and how very right she was.

When I went home that night, I didn’t tell Graham a thing. I didn’t want him to start worrying about our own baby, and I didn’t feel the need to unload on him. I actually felt surprisingly at ease about the events of the day, and when I jotted down a few thoughts and feelings in my notebook, as I sometimes did, I realised why.

‘People keep asking me if being a midwife hasn’t put me off having babies of my own,’ I wrote as I sat on our bed at home. ‘I think it has the opposite effect. I can’t wait to have my baby! If being a midwife has taught me anything, it is that, come what may, babies bring a great deal of happiness.’

‘Billy Jean King beat Chris Evert 6–0, 7–5. Did you hear?’ Graham called up the stairs to me.

‘No, missed that,’ I replied. ‘Been a bit busy today.’

‘Not too busy, I hope?’ Graham asked protectively. ‘Not in your condition!’

I loved that he was looking out for me, but I reassured him that I was absolutely fine, and that I was perfectly capable of working through my pregnancy, especially at this early stage as I was still only just into my fourth month. Despite the trials of the day I knew I had done a good job and I felt sure Rosemary and Billy’s baby would thrive, having such inspiring parents.

Graham and I would be good parents, too, I knew it. We loved each other very much, and as Billy had made clear so very touchingly, love really is all you need.