Читать книгу The Films of Samuel Fuller - Lisa Dombrowski - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

The Fox Years, 1951–1956

Fuller signed with Twentieth Century–Fox at the beginning of a tumultuous decade for the motion picture industry, a period that saw the end of the studio system. Production cutbacks that began in the early 1940s accelerated in the 1950s as the studios faced declining audience attendance, rising costs, and plunging profits. In an effort to counter the lure of television, radio, and other suburban entertainment options, the major studios shifted away from producing a balanced slate of A and B pictures designed for the whole family and looked to new strategies to differentiate their product. Dramatically reducing low-budget production, the majors concentrated their resources on spectacular, big-budget films that featured color, stereophonic sound, and widescreen processes, creating an experience unable to be replicated at home. At the same time, a piecemeal decline in industry regulation and censorship beginning in the late 1940s and culminating in the 1956 revision of the Production Code enabled more filmmakers to tackle adult-oriented fare that flaunted sex, violence, and social taboos to a degree not seen in mainstream domestic filmmaking since the early 1930s. Fuller’s contract with Fox enabled him to participate in many of these trends, as he had secured a job with a major studio that, at least temporarily, valued his penchant for visual experimentation and edgy material.

While Fuller’s decision to sign with Twentieth Century–Fox seems largely to have been based on his fondness for Darryl Zanuck, the studio’s longtime production head, Fuller’s background as an action director complemented the needs of the studio. From their first meeting, Zanuck and Fuller established a close relationship that flourished through the 1950s. Fuller expressed great admiration for Zanuck’s straightforwardness and commitment to strong storytelling, and Zanuck reveled in Fuller’s can-do spirit and real-life adventures. Both were equally fond of cigars and explosives, once apparently firing off a nine-millimeter German Luger in an underground screening room together.1 Although Zanuck’s interest in more “realistic” material remained firm, when Fuller arrived at Fox in the early 1950s the production head was steering the studio toward big-picture entertainment rooted in action and sex rather than the social problem films it produced at the end of the previous decade.2 As a director who had made a name for himself in action films but who still maintained an obsession with history and journalism, Fuller was a fine fit. All of the films he directed while under contract at Fox—Fixed Bayonets, Pickup on South Street, Hell and High Water, and House of Bamboo—were action-oriented war, crime, or adventure stories rooted in contemporary political and social conflicts.

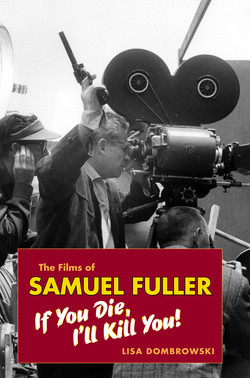

Twentieth Century–Fox’s production chief, Darryl Zanuck (left), at a birthday party for Samuel Fuller (right) during the shooting of Hell and High Water. Zanuck and Fuller had a warm relationship and worked closely while Fuller was under contract at Fox. Chrisam Films, Inc.

The classical norms embraced by the major studios as a means of ensuring clarity, coherence, and quality had a decided impact on Fuller’s work. Now he was operating within a system of long-standing production practices fully ingrained in workers at every level of authority, a system that directly and indirectly influenced the choices available to filmmakers. During this period, the narratives of Fuller’s films adhere to classical, generic, and cultural conventions to a degree never again seen in his career, and his visual style becomes more refined and polished. Fuller’s artistic instincts are not completely buried, however. With the proper material and the support of the studio they could come very much to the fore or, alternately, they could express themselves in a more subtle fashion, achieving his favored effects while still reflecting classical norms. The proof of Fox’s influence on the expression of Fuller’s aesthetic is most clearly seen through comparison with his one independent project during this period, Park Row. If the Fox films are Fuller restrained, Park Row is Fuller unbound; the difference is palpable.

The Trade-offs of Studio Filmmaking

As a director at a major studio, Fuller occupied a role defined by specific expectations, and as a director at Twentieth Century–Fox, his role was actively overseen by Darryl Zanuck. Under the modes of production utilized by the majors during the studio era, a director’s primary responsibility was the coordination of actors and crew during the shoot itself.3 The producer and studio managers typically left directors alone on set, relying on daily production reports, script supervisor notes, and rushes to confirm if a director was staying on time, on budget, and maintaining narrative and visual quality. The producer and department heads sought ideas and approval from the director during preproduction (script development, casting, set construction, wardrobe creation) and postproduction (editing, scoring), but at these stages the producer’s opinion trumped that of the director. At Fox, Zanuck was the top production manager, and he exerted overt control during pre- and postproduction. Zanuck started his Hollywood career as a screenwriter at Warner Bros. during the 1920s, and as production chief he closely supervised story development.4 He regularly selected literary properties and reviewed synopses, treatments, and scripts. When meeting the screenwriter and production team during story conferences, he dictated the direction of the conversation, offering general story ideas and line-by-line script notes. While Zanuck respected directors’ autonomy on set as long as they kept to the schedule and provided acceptable footage, he re-exerted control in postproduction, watching rushes, making comments to the director and editor, selecting takes to use, and ordering reshoots. A range of entrenched institutional systems and practices thus shaped Fuller’s degree of artistic control during this period, and Zanuck’s influence was particularly acute.

Although Fuller lost some measure of control over his films while at Twentieth Century–Fox, his contract provided him with an opportunity to direct higher-profile pictures while still retaining the ability to work independently. The seven-year option contract, signed in April 1951, stated that Fuller would render his services to Fox for twenty-six weeks as a writer and director on an initial film and, at the pleasure of the studio, also act as a producer for the film. Subsequent contract extensions also bound Fuller to Fox for half of every year, leaving the director free to pursue one outside motion picture or television show the remaining twenty-six weeks of the extension. When Fuller notified Fox of a starting date on an outside project, the studio had the right to preempt the project by dictating its own starting date on a new film, but Fuller then had to have twenty-six weeks later in the contract in which to complete his outside work. He had the freedom to write his own screenplays and to reject assignments at will. Fuller also was not obligated to submit to Fox any literary material, and he could offer stories and screenplays to other studios before showing them to Fox; in addition, his contract specified that only he could direct his screenplays, subject to his availability.5 Fuller’s deal thus protected a number of freedoms he held dear: the pursuit of projects he cared about, regardless of studio interest; the choice of where to develop his original stories and screenplays; the direction of his own written work; and the chance to produce his own films (if Fox so desired—it never did).

Fuller’s tenure at Fox introduced him to both the benefits and the restrictions of major-studio filmmaking. For the first time, his films employed stars, color, widescreen, and location shooting; he had the luxury to rehearse more, to shoot for a longer period, and to experiment with extended tracking shots and cranes. He was also assured that his films would receive wide, first-run distribution in top houses, supported by a national publicity campaign. On the other hand, Fuller no longer produced his own films, nor did he have profit participation or final cut. Most of his original screenplays were rejected by the studio, and except for Fixed Bayonets, he did not originate the stories for any of his Fox films. Finally, although he did write one script and a scenario for other studios while under contract, Park Row was the only independent film he was able to write, direct, and produce during his five years at Fox.

Executive oversight and the use of studio departments and crews led Fuller’s films to adhere more closely to classical narrative and stylistic norms while he was at Twentieth Century–Fox. The screenplays for his Fox pictures fit neatly into defined genres and feature tight, causally-driven plots free of the narrative digressions, didacticism, and offbeat humor that cropped up in various Lippert films. While Fuller’s dialogue remains punchy and his protagonists gruff, increased use of subjective narration, particularly in Fixed Bayonets, encourages greater alignment with his primary characters. Visually, Fuller’s films continue to develop the diverse staging strategies previously seen in The Baron of Arizona, as both long takes with camera movement and analytically edited scenes enable action to be fully covered from a variety of angles and shot scales. Fox’s state-of-the-art equipment, sound stages, and highly trained crews encouraged Fuller to craft intricately choreographed shots featuring extended tracking and craning as well as movement by multiple characters, shots he simply did not have the resources to attempt while at Lippert. At the same time, dialogue-heavy scenes are more likely to feature multiple camera setups and cuts from establishing shots into and out of tighter framings—conventions developed at the studios to ensure quality scene construction—rather than simply an extended master shot with inserts. The pressure to conform to classical norms during the Fox years smoothes many of Fuller’s rougher edges, resulting in the most elegant films of his career. Nevertheless, given the proper encouragement and appropriate story material, Fuller was still able to craft distinctively idiosyncratic films under the studio system, films that forcefully deliver truth and emotion.

Return to War: Fixed Bayonets

Fuller’s first picture for Fox, Fixed Bayonets, functioned as a transitional film, exploiting many of the same elements as The Steel Helmet while introducing Fuller to production on a larger scale. Released less than a year after the premiere of The Steel Helmet, again set during the ongoing Korean War, and starring the same grizzly, up-and-coming actor, Gene Evans, Fixed Bayonets appeared positioned to capitalize on its predecessor’s success. Production values were low for a Fox film but significantly higher than Fuller was used to at Lippert, and they are evident on the screen. Fuller still lacked a star-studded cast, shot the entire film on two sets on a single soundstage, and had one of the smallest budgets of any Fox picture that year; nevertheless, he enjoyed a two-month shoot and a $685,000 budget—more than triple his previous schedules and production costs—as well as access to a crane for the first time.6 The larger cast; swooping, intricately choreographed long-take cinematography; fake ice and snow; large munitions explosions; and realistic, functioning tanks all distinguish Fixed Bayonets from its lower-budgeted predecessor.

Fixed Bayonets follows a platoon left behind as a rear guard decoy on a snowy mountain pass as its soldiers attempt to hold off the North Korean army long enough to let the rest of the brigade escape. Leading the platoon are a lieutenant, two sergeants, and a corporal, Denno (Richard Basehart), who fears to assume command and cannot bring himself to kill. After the rest of the brigade has left, the platoon splits into two squads, one of which, led by Sergeant Lonergan (Michael O’Shea), establishes a series of observation posts and digs in; the other, led by Sergeant Rock (Gene Evans), sets mines in a pass, goes out on patrol, and holes up in a cave. In between enemy bombardments, the soldiers in the cave huddle together to keep warm, drink weak coffee, eat bad chow, massage their feet to ward off frostbite, and sleep when they can. A sniper kills the lieutenant, and Denno confesses to Rock that he is afraid of ever having to be responsible for the lives of other men. Rock tells him, “You gotta have the guts to lead.” After snipers bring down Lonergan in the middle of the minefield and a medic is blown up trying to retrieve him, Denno crosses the minefield to save him, proving he has guts but failing to keep Lonergan alive. Following another enemy artillery strike, a bullet ricochets through the cave and kills Rock, leaving Denno in command with just an hour left to hold back the enemy. As the platoon packs up to retreat, North Korean scouts and a tank come through the mountain pass. Denno devises a plan to take out the tank, kills his first enemy soldier, and earns the respect of his men. As the exhausted and injured platoon rejoins the rest of the brigade, Denno remembers Rock’s words: “Ain’t nobody goes out looking for responsibility. Sometimes you get it whether you’re looking for it or not.”

Fixed Bayonets is one of Fuller’s tightest plots and, when compared with The Steel Helmet, demonstrates how the classical narrative conventions championed by the major studios affected Fuller’s writing style. Working from a treatment written by Sy Bartlett, Fuller drafted an original outline for the story, the screenplay, and two revisions. Zanuck worked closely with Fuller during script development, focusing the narrative on Denno’s fear of command and arguing that nothing in the story must “cover or make fuzzy” this primary theme.7 In his notes on Fuller’s original outline, Zanuck suggested the plot structure, the use of voice-over, and the content of the final scene, all of which Fuller incorporated into his subsequent scripts. As a result of Zanuck’s oversight, absent from Fuller’s second Korean War film are the racially mixed unit, episodic plot, digressive episodes, and didactic interludes that characterized his first. In their place are more typical character types (the loud-mouth from Brooklyn, the wide-eyed farm boy) and a causally driven plot that carefully guides the viewer through the story.