Читать книгу Catch and Release - Lisa Jean Moore - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

I get irritated by a certain type of academic voice. I react at times with both envy and incredulity at the ability to make sweeping declarations about large-scale interconnected phenomena spanning time, space, and economies. These statements resound with a manly, assured forcefulness of Truth, and I nod along in supportive feminine pantomime. I secretly think: “How does he know that?” and “How can he say it so definitely?” Everyone else seems to buy it, so I shrug and go along.

The contemporary cultural meme of how men explain things, or mansplaining,1 so diverges somewhat from my own reaction to this kind of academic voice. It is as if I hold out hope that I can do womansplaining, my own way of claiming a valued and respected voice, without having to be an annoying know-it-all. I want to be able to break out of the standard performance of scholar and be valued as a significant contributor, even if I am less declarative and more circumspect. And yet I certainly don’t want my methodological rigor and status as a reliable narrator to be dismissed because I openly voice these internal dialogues. Instead of being seen as someone who produces knowledge in spite of this internal struggle, I want to deploy this struggle as an integral strength of my method and my scholarship.

Even as an undergraduate sociology student, I was drawn to symbolic interactionism, a theoretical and methodological perspective that examines the creation of social meaning. This sociological paradigm nourishes me at my intellectual core. I enjoy reveling in the creativity of meaning-making humans, learning and relearning the concept of the definition of the situation, and examining the unfolding human conflict inherent in wrestling with normative expectations. When making claims about my own research, I’ve always been more comfortable keeping my analysis on the level of the microsociological—symbolic interactionism’s bailiwick.

My brand of qualitative research—immersion in a field site, long unstructured interviews with humans, learning new skill sets from indigenous knowledge producers—serves as the basis for my interpretations about social life. So, for example, being on a blistering hot urban rooftop with a beekeeper as she carefully explains how to do a hive check becomes the basis for my grounded theories about the social world of urban beekeeping and its cultural significance. And watching a lab technician observing sperm through a microscope and using a hand tally counter, I can understand how sperm count comes to be pragmatically and discursively quantified as a measure of a man. As in all my empirical work, rarely do I stray too far from my data to make grand claims, relying instead on informants’ quotes for “evidence” of the claims I make. Deploying their words allows me to make larger observations—about human reproduction, the spread of disease, the world, or the climate—as a safeguard against my own grand theorizing or deploying my intellect.

When I signed the contract for this book, my lifeline and editor Ilene Kalish said, “Well, we don’t think this book will have a very large profile. Especially if you don’t answer any questions, just raise them.” Ouch. She referred to my previous books and my ambivalence in adding my voice to large-scale sweeping claims. Am I an academic wimp imprisoned by my femininity? Do I hedge my bets rather than stake my place as a knowledge producer? A dear friend encouraged me, after reviewing multiple drafts of my work, to liberate myself from my tendency to quote or genuflect textually to others. Why do I feel so uncertain about “proving something,” having a conclusion, or making a point? I do understand the critique, yet I can’t manage to wholeheartedly embrace the epistemic authority of making definitive statements rather than raising important questions.

Perhaps I am a day late (2 decades?) and a dollar short in trying to amplify my voice as a “knowledge producer”—someone who makes definitive statements about FINDINGS. During my graduate school years in the 1990s, the swirling debates about human subjectivity and epistemology generated lively discussions of who has the permission to access and create knowledge. In particular, we examined what qualifies a scholar as “legitimate,” especially one from an “othered” position. We analyzed the feminist philosopher Nancy Hartsock’s now oft-quoted lament about the plight of so many of us: “Why is it that just at the moment when so many of us who have been silenced begin to demand the right to name ourselves, to act as subjects rather than objects of history, that just then the concept of subjecthood becomes problematic?”2 We were attempting to come to terms with the opportunity to contribute to epistemology from our situated perspectives while simultaneously acknowledging that subjectivity itself was being dismantled.

As much as I want to join the club of those who can make larger pronouncements with the heft to back them up, to add to epistemology, there is always a tacit asking of permission, a split-second hesitation, or an implied qualification. The pleasures and dangers of reflexivity, adding the anecdotal reflection, can break up my inner tension. Instead of just saying something specific and firm, I opt to reveal some internal ambivalence couched in a humorous story. Writing from my own voice, grounded in my painstaking qualitative immersion, seems both self-indulgent and elusive in its legitimacy. This hand-wringing does feel particularly human, probably bourgeois, and most definitely feminine—similar to the ubiquitous apologizing of my sex. Perhaps this is what womansplaining looks like?

Thinking with Tenderness

While I am tentatively taking steps to move into, if not grand theorizing, at least less molecular theorizing, the clear waters of epistemological authority have been muddied by urgent calls to acknowledge our “becoming with nonhuman animals.”3 Just as Harstock called to interrogate the politics of the “death of the subject,” I now must confront my humanness as yet another position of superiority in knowledge projection. Getting a handle on my humanness and my ability to speak from my standpoint has been a grind.4 Ever so slowly, I’ve grown to proffer contingent feminist epistemological and empirically grounded claims. But this is further complicated by my recent turn toward nonhuman animal ethnography—multispecies ethnography. No longer is it simply a matter of contributing to knowledge—if creating epistemology is level 1, the academic field is now at level 2: the re-emergence of, and reckoning with, ontology. The travails of knowledge production have in some ways become subordinated to matters of ontology. I believe it is only through these interactional, entangled, minute observations and speculations that I can begin to contribute to the literature on climate change, geologic time, conservation ecology, and biopharmaceutical industry. I do this through my examination and movement toward an engaged becoming with horseshoe crabs.

At first the idea of having to take in more subject positions and ontologies while simultaneously re-evaluating my own position in a system of stratification (this time with animal others) became almost too much to handle. But ultimately, horseshoe crabs have offered me another fascinating and very personal opportunity. Through knowing and being with horseshoe crabs I have discovered again my voice as one co-produced through polyphonic contributions of willing, unwilling, and unknowing others, animal and human.

In what follows, I explore the entanglements of horseshoe crabs and humans—how these becomings, these assemblages, these social worlds of intraactions between crabs and people enable us to understand the world in a fresh way. Catch and Release is a book that has allowed me to take more risks with making claims and thinking beyond the microsociological. At the same time it has forced me to pay very close attention to the micro-intraactions between crabs, the sand, the water, humans, time, tides, and biomedicine. I am using the term “intraactions” from my reading of the feminist science studies scholar Karen Barad.5 Intraactions are a “mutual constitution of entangled agencies”—that is, the horseshoe crabs and humans materialize from within their relationship with one another. Moving from interaction, whereby humans and horseshoe crabs exist independent from one another, my analysis attempts to show how they become co-constitutive of one another.

This work is also decidedly political. Perhaps because of my training in feminist and queer studies, I am struck by the ways in which we humans perceive ourselves as other in relation to nature. This is a thoroughly constructed concept in which we separate ourselves from nonhuman animals in order to systematically exploit them (as well as the environment). Even when we express a desire to protect nonhuman animals or ecosystems, it is commonly in the service of human interests—they are extrinsically but not intrinsically valuable. In previous work on bees, sperm, and clitorises, I have investigated the narratives about the interrelationships between humans and body parts, and humans and animals, to generate ideas about the narrators and their relationships to animals/nature. I believe it is possible to shift our ingrained hierarchical way of understanding and relating to nature/nonhuman animals by engaging in intraspecies mindfulness. This practice of intraspecies mindfulness, the constant situating of ourselves in a mesh instead of a hierarchy, allows for a natural empathy to unfold between humans and nonhuman animals (and the greater environment).6

I’ve slowly and sometimes painfully come to understand that my feminine socialization, an insecure femininity, is in many ways an asset. Wrestling with my own positionality as a knowledge producer has meant that I privilege the process of knowing versus the final product of what is known—once and for all. I work to understand how historical and contingent findings are actually powerful, more so perhaps than grand pronouncements. I am a tender thinker who doesn’t always think I know what’s right, and I use this reflexive tentativeness to create a more textured and nuanced interpretation of the social and natural world and how we come to know it.

Encountering Horseshoe Crabs

After completing Buzz with Mary Kosut, a book that explored urban beekeeping,7 I was excited to continue examining the ideas that emerged from that project. Specifically, I wanted to explore intraactions between humans and animals in urban settings. Horseshoe crabs emerged as a possible species since they are available to me in Brooklyn, and they have so many applications in human worlds. The fact that I had been encountering horseshoe crabs since I was a child bolstered my intellectual interest.

Becoming with horseshoe crabs has truly been a constant thread running through the course my life. I grew up sharing the ecological habitats of the horseshoe crab as I recklessly “played” with them on the beach as a child. As an adolescent, I feigned marine expertise and showed off my fearlessness to my shrieking peers who were unfamiliar with the burrowing prehistoric crab. As a new parent, I introduced the crabs to each of my daughters in turn, living out maternal dreams of instilling courageousness, intelligence, and reverence. Raising three girls in Brooklyn, I want them to have some sense of Donna Haraway’s naturecultures, within which we co-exist.8 In other words, I want us (the girls, myself, other people) to figure out how to be better neighbors with all of Earth’s inhabitants. I’ve used the crabs as a conduit to do that work by making the kids aware of the crabs’ existence and how to momentarily ease their suffering. For example, the girls know to flip over the crabs when they are on their backs so they don’t dry out.

As a sociologist, during the fieldwork and writing of this book, I’ve mined these memories, and in bringing them out into the light of day, I’ve realized that horseshoe crabs have always been a part of who I am. This book is an articulation of that understanding, one in which I explore how I’ve come to know myself and the crabs—and a speculation on what this becoming with means to me and to broader interspecies relationships.

My early investigations to determine the feasibility of this project led me to some truly serendipitous connections with expert scientists. Mark Botton, the marine biologist I follow most closely in this project, is on the faculty of Fordham University and conducts much of his fieldwork at Plumb Beach in Brooklyn, where I live. Because I met Mark and Christina Colon of Kingsborough Community College, my project was able to pick up steam, enabling me to gain entrée and rapport with Jennifer Mattei of Sacred Heart University (Connecticut). I especially admire Jennifer’s brilliance at making her intellectual and scientific work part of larger projects of ecological restoration. These scientists invited me to attend international meetings of horseshoe crab experts in Japan. At these meetings, I met even more individuals who became informants for my project. Later, during another field visit, I traveled to Cedar Key, Florida, and interviewed Jane Brockmann and Mary Hart while I participated in a 3-day horseshoe crab–tagging workshop. To understand the invaluable role of conservation and population dynamics, I interviewed Gary Kreamer, aquatic resources educator for Delaware Fish and Wildlife, and Dave Smith of the Leetown Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, who offered astute expertise. While attending a celebration of Carl Shuster’s instrumental work in horseshoe crab science and conservation, I met Ron Berzofsky, who provided background on the pharmaceutical industry. Tom Novitsky has been an invaluable and patient contact for me, in particular for helping me understand horseshoe crab blood.

Beyond attending these professional and scientific events, I also spent a lot of time in the field—on the beaches of Brooklyn and Long Island’s South Shore. I learned to find and identify juvenile crabs during my time with Mark, and I discovered how easily these fieldwork skills became part of my own leisurely walks on the beaches with my daughters. Reaching down and finding juvenile horseshoe crabs the size of small pebbles or stones, nestled in the sand, is an immediate and visceral reminder that we share space with ecological others. Far more than just a clever environmental parlor trick, demonstrating the variable meanings of habitat—to and for whom—literally means to tread lightly: It matters where we step.

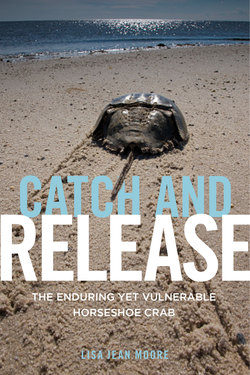

Horseshoe crab on Plumb Beach, 2014. Photo by Lisa Jean Moore.