Читать книгу Catch and Release - Lisa Jean Moore - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Fieldwork in the Mudflats

Balancing six baby horseshoe crabs in my hand, I rotate my wrist to keep them all in my palm. They are wriggling and jostling one another, trying to get some traction on my skin. Taken from their nestled watery mound into my clammy human hands, being held above their home in the dusky sea breeze must be strange. My feet are deep in the muck of the tidal flat, squishing sandy silt between my toes. The late summer sun fades behind me. I feel alive and excited by my fieldwork site. The thrill of being outside with the crabs is invigorating, different from the usual anxiety I feel before an interview with a merely human informant, anxious that any misstep could jeopardize my rapport or entrée. These horseshoe crabs are my reason for being here, I tell myself, but is it just an excuse to enjoy another day at the beach, filthy as this urban shoreline is? I think, feel, and become with the vibrant matter around me—the bubbling of my sinking feet, the tickling of the tiny crab legs, the burn of the sun on my back. I revel in the odors and sounds, the smell of the sulfury tidal flats, the calls of the shore birds, the hum of the Belt Parkway.

* * *

What has drawn me to this beach, month after month, year after year? I have shifted my focus from all things human—body fluids, anatomies, sexuality, interpersonal relationships—to insects and animals—bees, horseshoe crabs. Many friends, colleagues, and family members have asked me why I am researching horseshoe crabs since I am a sociologist, not an ecologist or marine biologist. Sometimes my answers betray my exasperation, and I stumble over my words. I recount the greatest hits of horseshoe crab talents, their capacities, their use in human applications, their exploitation. Yet, over time, I have come to resent the question. I feel as if I am being asked to convince humans that another species can matter and be worthy of concern as either a surrogate or a product for humans. The arrogance of the sentiment “Tell me why you care so I can decide if I care” frustrates me. I want to protest that the foundational “What’s in it for me?” query is the basis for the very human exceptionalism and capitalist consciousness that has gotten us into this environmental mess: global warming, massive species extinction, estrangement, disenchantment, alienation. And then I come back to relative calm, realizing that I must gradually build a case for the horseshoe crab. Just as it was a process for me to understand how an ontologically based interpretation of things can have its own intrinsic value, I must now translate that process for others. Generally, the way to garner that interest, concern, or empathy is to bring it back to the human, the self.

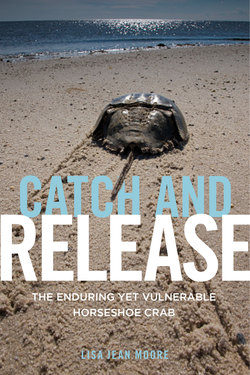

Holding baby horseshoe crabs in the palm of my hand. Photo by Lisa Jean Moore.

I have been handling horseshoe crabs since I was a child on the beaches of Long Island, New York. Running down the shore, telson—the tail—in hand, I terrorized my little brother. No compassion toward the crab as it bucked back and forth gesticulating its legs in a desperate attempt to defend itself. Separating amplexed—attached—crabs was also a favorite early summertime activity, and in my youthful stupidity and human hubris I asserted how I was helping the crabs to “stop fighting.” Through endless summer days, we’d have contests to see who could throw the crab further into the sea, our own version of playing horseshoes. Torture of animals is a sign of certain psychopathologies in children, and if it had been kittens we tossed into the sea by their tail, my parents would have certainly intervened—but the horseshoe crab raised not an eyebrow. My re-introduction to the crab, many years later, makes me shudder at my callous girlhood antics. When I began this research project in 2013, perhaps it was some sort of psychic penance for the sins of my former self.

Beyond a sentimental attachment to crabs, much later in life I become aware of horseshoe crabs’ vast contributions to human life through their sacrifice for biomedicine, fishing, and evolutionary theories. As I have written this book, horseshoe crabs have transformed my awareness of the world. They are both materially wondrous as well as symbolically generous. Observing the crabs, their habits, movements, growth, I’ve come to appreciate the shoreline in a new way. Like honeybees, horseshoe crabs are designated an indicator species, a biological species that provides useful data to scientists monitoring the health of the environment. Through associations and extrapolations, scientists are able to track the migration, health, and fertility of other species and can infer the sustainability of habitats. Indicator species, also known as sentinel species, are useful for biomonitoring ecological health, and horseshoe crabs can serve as a proxy for the health of shorelines. If the horseshoe crabs leave, migrate, or die, that indicates that the environment is degraded. I, too, have come to see the horseshoe crab as signifying larger ecological and sociological trends—rising seas, biological interdependence, geologic time.

My study centers on interviews with over 30 conservationists, field biologists, ecologists, and paleontologists and over 4 years of fieldwork (2012–2016) at urban beaches in the New York City area; natural preserves in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan; and marine research sites in Cedar Key, Florida.1 In Catch and Release, I explore the interspecies relationships between humans and horseshoe crabs—our multiple sites of entanglement and enmeshment as we both come to matter. As I show, crabs and humans are meaningful to one another in particular ways. Humans have literally harvested the life out of horseshoe crabs for multiple purposes; we interpret them for understanding geologic time, we bleed them for biomedical applications, we collect them for agricultural fertilizer, we eat them as delicacies, we capture them as bait. Once cognizant of the consequences of harvesting, we rescue them for conservation, and we categorize them as endangered. In contrast, the crabs make humans matter by revealing our species vulnerability to endotoxins,2 a process that offers career opportunities and profiteering from crab bodies, and fertilizing the soil of agricultural harvest for human food. In these acts of harvesting, horseshoe crabs and humans can apprehend important ecological events: geological time shifts, global warming, and biomedical innovation. My work situates the crabs within my own intellectual grounding in sociology; however, this sociological perspective is not seamless, it is rife with debate.

A major contribution of sociologists to contemporary thought is our production of theories and methods to determine, measure, and interpret social stratification and human inequity. Any introductory sociology course worth its weight provides students with critical thinking tools to examine race, class, gender, sexuality, age, and ability as social constructs that constrain our lived experiences. Armed with sociological insights to understand racism, classism, sexism, heterosexism, ageism, and ableism, the student explores how personal feelings are entangled with structural location. As a sociologist, I’ve made my living analyzing, teaching, and investigating aspects of human inequity, but I’ve recently come to consider the ways we determine the relative status, rights, or power of nonhuman animals. For instance, how do we explain how our companion animals—any cohabiting dog, cat, fish, or hamster—rank more highly than those pesky pigeons, rats, or roaches? What are the mechanisms we use to justify the relative worth of animals “scientifically proven” to be “closer” to us—such as gorillas, chimps, and other primates—versus those deemed more strange and distant—such as crickets, rattlesnakes, or frogs? The domination of humans over all other beings has created an assumption that our species has more value and, thus, has the right to act upon other species in our own interest. Speciesism, the belief in the inherent superiority of one species over others, was coined by the British psychologist Richard Ryder in Victims of Science: The Use of Animals in Research and popularized by the Australian philosopher Peter Singer.3

Speciesism is not just a ranking system of humans over all animals. Rather, humans create an even more specialized way of determining the worthiness of an animal—worthy of our care, our protection, our attention, and our love. How much we care seems to be very closely associated with how we regulate our scientific research and handling of animals. During an all-day visit to several shoreline field sites in Connecticut, the conservation ecologist Jennifer Mattei and I engaged in a philosophical discussion about the relative compassion for shorebirds compared to horseshoe crabs. I asked why so many seem to rank birds above the horseshoe crab. “It’s because it doesn’t have a backbone,” she instantly replied. I laughed, thinking she was joking and that the answer had to be more complicated than that. Although she was driving, she turned to make eye contact, and said, “I could crush a horseshoe crab, and no one would care, but if I did it to a bird, I would be arrested. Any research with animals with a backbone has all these protections. It’s total human bias that things more like us [require] more protection than things not like us.” I nodded, coming to terms with the fact that maybe it was as simple as that. She continued, “Who cares about a spider when they don’t have as many neurons as us and can’t feel what we feel? It’s the whole vertebrate-invertebrate divide.”4 Jennifer is right in the fact that the lack of a spine has had serious implications for the social status of the horseshoe crab and other invertebrates. Insisting that a backbone is required to feel pain creates a definitional absolute that leaves horseshoe crabs and other animals in an impossible position. Their responses to injurious stimuli are interpreted as something other than affect—a reflex—and as such, compassionate care does not need to be rendered. Despite mounting evidence,5 this popular and intransigent belief among many humans that animals without backbones do not feel pain influences our dismissive treatment of 95% of the total number of species on earth.6 But returning to horseshoe crabs specifically, what are the other distinguishing characteristics of this species?

Horseshoe Crab Biology and Anatomy

The ocean-dwelling horseshoe crab of North America, Limulus polyphemus, is a strange-looking animal. It crawls along the ocean floor with its maroon helmet-like hard-shelled top, the carapace, made of chitin and proteins. It has 10 “eyes” and six pairs of legs and claws underneath. In addition to its two compound lateral eyes, its other eyes are light-sensing organs located on different parts of its body—the top of the shell, the tail, and near the mouth. These eyes assist the crab in adjusting to visible and ultraviolet light and enhance adaptation to darkness in various environments, aquatic and terrestrial.7 A crab uses a nonpoisonous 4–5 inch hard tail, called a telson, to steer or right itself when it is overturned.8 The telson is dragged in the sand as the horseshoe crab lumbers along the shoreline. Adult crabs weigh 3–5 pounds and are 18–19 inches in length from head to tail for females (males are a few inches shorter). They can live for about 20 years. During spawning, they are either on the beach around high tide or swimming in 2–3 feet of water. When not spawning, they crawl along the bottom of the ocean at depths of 20–400 feet.9 On the shore, they are “slow and easy to catch” making them an ideal species for field biologists to study and to engage students.

Despite their spiny and spiky exterior, they are also comical to human eyes. As described by the biologist Rebecca Anderson, the first time she worked with horseshoe crabs she “pretty much fell in love with them because they look like these fearsome creatures with armored bodies and all their legs, but they are ineffectual as defenders. And they look so adorable when they walk on land.” It is difficult for most humans to observe horseshoe crabs in the water, but they have been described as “rather graceful compared to their tank-like appearance when they come to the shore.”10 Omnivorous creatures, they eat mostly clams and worms. They do so by crushing and grinding their food with their legs—or, more accurately, their knees—and shoveling the food into their stomach.

Anatomical illustration of the horseshoe crab. Illustration by C. Ray Borck.

Globally, there are four species of horseshoe crabs living on the continental shelf—one in North America, Limulus polyphemus, and three in Southeast and East Asia. The three species of horseshoe crab in Asia are Tachypleus gigas, Tachypleus tridentatus, and Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda.

Some humans have been drawn to the horseshoe crab because it unlocks secrets about the “sea of life.” With a fossil record to verify its ancient lineage, the horseshoe crab is among the oldest old. According to geologist Blazej Blazejowski, when traced by looking at modification by descent, crabs haven’t changed morphologically over tens of millions of years and as such are stabilomorphs, organisms that are morphologically stable through time and space. Their closest relatives are trilobites, which lived from 510 millions years ago. Amazingly, the horseshoe crab has survived longer than 99% of all animals that have ever lived.11 One of the reasons the species have survived for so long is because of the composition of horseshoe crab blood cells called amoebocytes. The blood is copper based, and when it hits the air it turns blue. Because of the chemicals in the ameoboyctes, the horseshoe crab’s blue blood coagulates when it detects contamination. This instantaneous reaction to threat through clotting protects the animal from harm. It is this very quality of their blood, the ability to transform into a biopharmaceutical gel, that has been used to insure the safety of all injectables and insertables in human and veterinary applications.12

These ancient species are also remarkable because they are primarily aquatic, coming onto the shore for spawning and nesting for brief periods every year. Indeed, if we accept the anthropologist Stefan Helmreich’s definition—“the alien inhabits perceptions of the sea as a domain inaccessible to direct, unmediated human encounter”—then horseshoe crabs are aliens.13 Unlike many domesticated animals or pets, these aliens are not intimately knowable since their primary place of residence is uninhabitable by humans. Adding to their alien-ness, horseshoe crabs are not easy for the layperson to categorize. They live in the sea, but some suggest they look like spiders. They are sometimes attached—“amplexed”—to one another. (You find yourself asking, Is one of them a baby? Is it catching a ride? Are they fighting? Are they mating?) They are prehistoric, and yet they seem so vulnerable. On land, they are practically defenseless, writhing helplessly when upside down with their fragile bits exposed to hungry birds.

Contrary to their name, horseshoe crabs are not true crabs. They are not even crustaceans. Taxonomically they belong to the same broad category that crustaceans do, the phylum Arthropoda—meaning that as invertebrates they have no backbone or inner skeleton; they have jointed legs and a hard outer shell, an exoskeleton, which protects a soft body. Horseshoe crabs are chelicerates, belonging to the same group that includes ticks, spiders, and scorpions.

After spawning during high tides in March through July, the North American species buries its eggs, which develop within the beach sediments after a couple of weeks to reach the trilobite (first instar) larval stage.14 They become reproductive adults after 16–17 molts or 8–10 years—which is slow growing for a marine invertebrate. Molting is the process of shedding the old shell and emerging from it with a new body. At first this body is soft and small, but it will swell with water and increase in size as the shell hardens.

A female horseshoe crab returning to the water at high tide on Plumb Beach, Brooklyn. Photo by Lisa Jean Moore.

Significantly, humans have been able to breed crabs in captivity, but they cannot get them to live beyond their tenth molt—at that time the crabs die instead of surviving through the remaining 6–8 molts and becoming reproductive adults. Scientists do not understand why this might be so.15 Our inability to replicate “natural conditions” for horseshoe crabs means that their reproduction must be primarily studied in the wild. In my experience studying horseshoe crabs when they spawn, there is a great deal of physical contact between humans and crabs. Picking up crabs is relatively simple since they do not pinch, bite, or sting. And they are not too fragile to be handled. As the biologist Mark Botton, one of my key informants, describes them, “They are tough, and ancient, and in many ways indestructible. They are the perfect species to teach undergrads about field biology since they are so easy to catch.” Another of my informants, the esteemed horseshoe crab scientist Jane Brockmann, adds, “What I like about them is that they are predictable. Breeding on the new and full moon high tides makes it pretty predictable. So you can take a class out there and expect to find something.”

My Intellectual Path to Horseshoe Crabs

Sociology, as a discipline, is historically indebted to humanism. In the Western tradition, the human is viewed as the ultimate social/rational/political being: one that is able to perceive the world, think about it, and communicate about that world back to others. The doctrine of humanism affirms the existence of a thinking ego, a self, or an I—the fact that we all share the ability to conceptualize our own respective selves demonstrates a sort of harmonious connection among us, which in turn demonstrates our superiority over all other entities, living and nonliving. For centuries, scholars have explored the role of consciousness and reason as the foundation of our autonomy. We are the only beings who are capable of giving anything meaning or of exerting our influence within the world. Humanism is a vexing philosophy because it is both liberating—freeing us from supernatural explanations over which we have little control—and damning—bogging us down in endless debates about who gets to count as “human.” Sociology has made its business studying (un)harmonious connections, investigating the dynamics of social order, social problems, social organization, social control, conflict, and cooperation. But in the process, sociologists have overwhelmingly privileged humans in their analyses and interpretations.

As I was trained in the humanist traditions of sociology’s sub-field of symbolic interactionism, my original research studies took the human as the starting point of all methods of inquiry. I am a feminist medical sociologist who was educated in grounded theory in the early 1990s by Adele Clarke, and I have occupied this strange position of not really fitting in as a legitimate member of either the sociological or cultural studies worlds. “She’s not sociological enough,” I’ve overheard more than a few times—particularly because my work resists quantification toward overarching meta claims, rules, or laws about “society.” And at the same time, my use of methods is often suspicious to cultural studies folks who fear it is a form of nonreflexive data generation and Truth (with a capital T) claims. Since my methods act toward the world as if it exists, no matter how it is constructed, I start my projects with what I consider to be material realities. These are contested, politically, and heterogeneously represented realities, and yet they are still material realities. I have shown that honeybees die, clitorises disappear in genital anatomy textbooks, and sperm counts decline. Understanding how we co-produce the conditions of these material realities and then work to interpret them is, in part, my job.16

I came of age intellectually at the time of what some academics called the “Science Wars,” which were characterized by fervent debates about scientific truth claims and social constructionism—as well as the rise of queer theory and the influence of interdisciplinarity and, more specifically, cultural studies in social science. I learned how to become a qualitative sociologist through methodological training that rejected strict adherence to positivism or the creation of singular and universal social facts. At the same time, my empirical training demanded that I measure things by relying on vaguely positivist tools to categorize and apprehend the social world. For example, establishing categories for sexual identity for an interview questionnaire required lengthy in-class debates about the formation and rejection of certain static, singular categories or statuses—endless debates about “What is a lesbian? What is bisexual?” The solution was “self-identification,” a sort of work-around to avoid a priori categories. Yet still, when conducting the interview, the informant was asked, “What is your sexual orientation?” And when writing up the analysis of the data, informants were neatly placed in categories as if they were self-evident and transparent—measurable, real, and singular. In other words, the category of “lesbian” always became reified or real in the process of trying to make it emergent through informants’ own words.

Over the last several years, my work has shifted toward a decidedly posthumanist frame where I feel the work resonates with the intellectual project of new materialism that considers all matter (human and nonhuman, objects, nature, technologies) as having agency or the ability or potential to make action happen. The move from humanism and speciesism means that relationality is not just between human beings but between humans and animals or between horseshoe crabs with one another, the sand, the sun, the tides. In particular, I frame this book as part of the new materialist writings exemplified by the work of feminist scholars such as Karen Barad, Mel Chen, and Jane Bennett.17 These scholars’ work demonstrates the active participation of the nonhuman and human, the animate and inanimate in social life and social order. Posthumanism de-centers the human being as the foundation of all ontological inquiry, challenges the self-anointed autonomy of the human species as rational selves, and seeks to construct a multifaceted idea of what it means to become human. Feminist new materialism, a form of posthumanism, engages with the relationship of matter to social and cultural interpretations. Matter is commonly understood as something distinct from our thoughts and sacred meanings; it is commonly defined as something that occupies space and has mass. Theorists in this area explore the ontology, or essence of being, of matter as deeply consequential for how the world comes to be known and enacted.

Horseshoe crabs and I are entangled in a world of becoming; as we intraact, we make each other up. As Catch and Release argues, human and horseshoe crab bodies materialize based on our interdependent relationships—polluting resources, generating commerce, exploiting medical capacities. We are enmeshed in heterogeneous worlds of the local, urban, global, ecologic, and geologic. In my earlier book, Buzz, Mary Kosut and I discuss how honeybees and humans are entangled in a world of pesticides, global food production, urban renewal, and species disintegration.18 The human/honeybee nexus also reveals our entanglement in a toxified world of interdependence. The cultural theorist Cary Wolfe, borrowing from Haraway’s cyborgs, argues that we have become fundamentally “prosthetic creatures” with an ontology that has “coevolved with various forms of technicity and materiality, forms that are radically ‘not-human’ and yet have nevertheless made the human what it is.”19 For example, I come to matter in collaboration with the honeybees that pollinated my food and worked to shape the industrial food supply. And even if I had never apprehended a horseshoe crab, they have fertilized the land before me and changed biomedical production, just as I have circumscribed the bees and crabs lives and bodies through my enactments of being human and using resources.

The animal familiars, including horseshoe crabs, who make us what we are, companion species who have helped stabilize our bodies, and our selves, remain entangled in complex multispecies worlds.20 For those of us whose health is fostered by government and corporate apparatuses, we exist in our current form as human because horseshoe crab blood has deemed our biomedicalization safe. Quite literally, our inoculated, pharmacologically enhanced, vaccinated bodies exist in their current status through a collaborated becoming with horseshoe crabs.

Anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss is often paraphrased as stating that “animals are good to think with.” Here he means that human’s interpretations of animals can offer very fruitful structures and frameworks for generating concepts and establishing larger connections between ways of thinking. Humans use animals to think with when we create metaphors and similes—“she’s as busy as a bee,” or “he’s as brave as a lion”—or when we manufacture sports mascots. More specifically, academics use animals to think with as a means of understanding sociality. In my own collaborative work with bees and even in some ways with my research on sperm, I have used these nonhuman entities to reveal meta-level analysis about contemporary masculinity and types of endangerment.21

Social theorists are not the only ones, or the first, to see the wisdom in deep engagement with animals. While attending the celebration of the work of the 96-year-old Carl N. Shuster, Jr., the world’s leading authority on North Atlantic horseshoe crabs, in June 2016, I was struck by his captivating combination of philosophical, naturalist, and artistic sensibilities while speaking about horseshoe crabs. “You want to know what’s going on with the crab, you ask it. Heck, you want to know what’s going on with the ocean, you ask a crab, too. You have to get down there with them, and just watch them and for a long time. Over a long time, you will start to know things.”22

Horseshoe crabs are good to think with. In Catch and Release I make many connections among our contemporary biomedical, geopolitical, and ecological environments while also pushing my analysis and method to show we must move beyond seeing the bee, or the sperm cell, or in this case, the horseshoe crab as merely a lens that reflects and refracts human life. Rather I argue that, not only are the crabs among us, but they are also in us (through their blood), and they are in many ways becoming us as we are becoming them. I rely on meditations on my methodological choices and fieldwork notes to illustrate this enmeshment. From both a scholarly and personal position, I muse about the ways our fates are in some ways deeply entangled, and yet the crabs reveal deep human vulnerabilities—to toxins, the climate, the ocean, and time.

Human Exploitation of Crabs

Catch and Release investigates and grapples with these questions: How do humans exploit the crabs, come to depend on them, and fret about their welfare? How is it that humans are simultaneously saviors and villains in stories about the crabs? Have the crabs met their match in humans after 480 million years, or are humans, in their speciesist ignorance, insignificant to the crabs’ geologic legacy?

As a qualitative sociologist, my method of investigating these questions is to be with the crabs and the people who work with them. In the summer of 2015, I attended the Third International Workshop on the Conservation of the Horseshoe Crab in Sasebo, Japan. I share my field notes from the first day:

Fighting my bleary-eyed jet lag and fitful sleep on a tatami mat, I finger through my registration packet for the Third International Workshop on the Science and Conservation of the Horseshoe Crab. I am sitting on a generic conference chair in a hotel ballroom in Sasebo, Japan, scoping out the fellow humans. Attending mostly sociology and gender studies academic meetings in my professional life, where colleagues routinely complain about the lack of heterogeneous representation, it is interesting to see such a diverse audience of humans. I’m not sure there is any one dominant ethnic group in this crowd of natural scientists, conservationists, ecologists, and wildlife educators. I smile at the man next to me, looking down at his name tag—Jaime Zaldívar-Rae, Anahuac Mayab University, Merida, Yucatan, Mexico. He nods to the stage, as opening remarks are just beginning. A slightly hunched Japanese man in a loose-fitting suit is helped up the steps.

The 87-year-old Mr. Keiji Tsuchiya is a former middle school teacher who dedicated his life, in part, to horseshoe crab conservation. He is a founding member of the Nippon Kabutogani wo Mamoru Kai (Japanese Society for the Preservation of the Horseshoe Crab). During his presentation, Mr. Tsuchiya speaks about the origin of his “love” for horseshoe crabs. As a 17-year-old drafted soldier, working off the shore of Hiroshima, he recounts through a female translator, “I saw a flash, heard loud sounds, and saw a mushroom cloud, and then all the sudden it was very dark and I could only smell burning.” Once he arrived on the shoreline, Tsuchiya navigated through the burning structures to help line up victims side by side and vividly recalls the cries of “Give me water, sir.” Pausing dramatically to choke back tears, Tsuchiya shares, “I can still hear the words of victims in their last moments begging for water.”

After the recovery efforts, he continued his career training to be a middle school teacher.

Then in 1961, he witnessed 10,000 crabs dying on the beach because they missed the tides to return to the sea. This experience made a serious and lasting impression on Tsuchiya. He joined the Kasaoka-shi Kabutonagi Conservation Center, where he worked for many years. Although I speak no Japanese, his passion is obvious as he grips the podium: “This mass horseshoe crabs death occurred because they were drying out and asking for water.” Raising his finger, he continues, “This memory of the atomic bomb where people were asking for water sounded just like the horseshoe crabs to me. ‘Water, water, please give me water, sir.’ It is the same. And since I have dedicated my life to love and conserve horseshoe crabs and to being a nuclear-free peace activist.” He then steps aside from the podium and says in English, “I love horseshoe crabs.” Two hundred international horseshoe crab experts jump to their feet and applaud.

* * *

The purpose of Catch and Release is to examine the myriad ways horseshoe crabs dramatically merge with human lives and how these intersections steer the trajectory of both species’ lives and futures. Again and again, I illustrate how we are enmeshed. Sometimes, as in the experience of Mr. Tsuchiya, intraactions are framed in the spirit of a companion species—but overwhelmingly, as explored throughout the book, horseshoe crabs are constructed and used as an exploitable resource. And still horseshoe crabs have a mighty past, suggesting a certain invulnerability, whereas comparatively humans are temporary. More on this later.

I detail Mr. Tsuchiya’s story because I was and continue to be struck by how he puts horseshoe crabs on the same ontological plane as humans—both are worthy of similar grief. I could imagine some people finding this strange. To many, the comparison between human victims of a notorious nuclear bomb with beached, drying out horseshoe crabs can seem outrageous or callous. Standing in the ballroom, I did find myself looking around at those applauding and wondering if any of them thought it a strange opening to the meeting. These were mostly scientists, after all—pragmatic, humanist, positivist. Most of them were accustomed to using horseshoe crabs as research objects where pain and death were possible outcomes. And yet it was clear the audience was touched—emotionally in sync with Mr. Tsuchiya’s story and able to tap into a sense of compassion for the crabs and their struggles.

One of the humans in that audience was the biologist Bob Loveland. During a smaller meeting in New York City, Bob explained the modern periodization of the horseshoe crab. The first threat to the horseshoe crabs occurred at the beginning of the last century, when the local populations of crabs began to decline precipitously. In the United States, horseshoe crabs were hand harvested and ground up for agricultural use until being replaced by chemical fertilizers in the 1950s.23 After a measurable dip in their numbers, the population bounced back in the 1970s. Today, harvesting horseshoe crabs for use in agricultural fertilizer industry is no longer practiced in the United States.

The second threat began in the 1990s and is ongoing. Crabs are caught by fishermen to use as bait for eels (Anguilla rostrata) and whelks (Busycon carica and Busycotypus canaliculatum) and are worth an impressive 5 dollars each.24 In the United States, the harvesting of crabs is supposedly controlled, limited and managed through a patchwork of intra- and interstate regulations including those by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission and the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission. Despite these regulatory apparatuses, many of my informants believe there is great variability in enforcement, and as a result, there are several reports of a black market in horseshoe crabs.

The third and not insignificant threat to horseshoe crabs is their harvest for biomedical use. The crab’s blood is used to create Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL). Since the 1970s, in order to get approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for any pharmaceutical product such as injectable, implantable, or biological/medical devices, there must be an LAL test conducted to detect any possible bacterial contamination.25 These tests have become biomedical standards in mandated pharmaceutical testing protocols. There are fears of international poaching of North Atlantic horseshoe crabs as Asian species dwindle and biomedical demand grows. Currently in the United States, for biomedical purposes, horseshoe crabs are caught, bled, and released. As discussed at the meetings in Japan, since there is no catch-and-release practice in China, crabs are caught and bled to death. I call this catch and kill. Once the Asian horseshoe crabs are extinct, some researchers worry, there is potential for a black market in North American horseshoe crab blood and international poaching.26 (This use of horseshoe crabs is explored in chapter 4.)

The fourth threat to crabs is the loss of habitat occurring through what Loveland identifies as the “ongoing sea level rise and our response to it.” Horseshoe crabs are a type of sentinel species signaling the strain of environmental stressors, the rapidity of ecological degradation, and how human engineering might exacerbate downward trends.

Intraspecies Mindfulness with Horseshoe Crabs

A large part of my qualitative research over 4 years has been working at Plumb Beach as a research assistant to Mark Botton, a marine biologist at Fordham University, and Christina Colon, a conservation biologist at Kingsborough Community College. They have taught me how to do census counts of horseshoe crabs. Additionally, they trained me how to assess the quality of a horseshoe crab carapace and how to identify the fouling organisms, or animals, that attach to carapaces. Over the years, I have become friendly with Mark and Christina, and I hope my participation in the fieldwork adds an additional intellectual aspect to their biological and ecological interventions. Over the years, I think I have also developed a skill for quickly finding juvenile horseshoe crabs in the sandy and muddy estuaries, which I describe below.

On the tidal flats at Plumb Beach, collecting juvenile horseshoe crabs in a plastic take-out container as part of a timed count. Photo by Lisa Jean Moore.

* * *

From my field notes representing a typical day of horseshoe crab field biology:

It’s August 13, 2015. We are doing a juvenile count in the mud flats at Plumb Beach. I’m dressed in rubber boots, waterproof shorts, a tank top, and a floppy hat. Feeling cocky, I tell Christina that I will collect more crabs in our timed task, placing juveniles into a plastic take-out container for subsequent measurement. The four of us—Mark, Christina, a graduate student, and I—separate. Mark says “go” and I crouch down in the muddy sand, distinguishing between the mud snail and baby horseshoe crab trails. It takes me several times to tell the difference between these tracks in the sand, but now I am becoming more skilled. I sift quarter- to dime-sized mounds of sand under inch-deep water to find the babies. I plop them in the container and crawl down to the next area. With little regard to the crabs’ experience, I feel happy. I am doing my job well, urged on by the side challenge to move quickly. Looking down, my container is full of crabs upside down, sideways, bending to and fro.

Taken from their wet, gritty, dark, and solitary self-fashioned mound, the crabs jostle against one another and the plastic slippery container walls. I scurry about feeling a tiny bit of accomplishment at each crab I identify and capture. “Time,” Mark shouts, and I run over to see who has more. Christina’s container is definitely more full than mine, and I concede. We then measure each crab with calipers. Afterwards I put each individual crab back to the water, away from one another but several feet from where they originally were lodged.

Mark Botton using calipers to measure juvenile crabs as I record their size on a data sheet. Photo by Lisa Jean Moore.

After a few hours, I leave the beach. Driving home through Brooklyn, I think about whether or not I really connected with the crabs. The audacity of this thought process makes me laugh—who am I kidding? As if those crabs and I had any communion? I had no conscious thought about them other than as numbers to be added to my pile, then numbers to be written on a chart, later to be added to a spreadsheet, and finally quantified to some sign of health of the species on this spit of land in Brooklyn. Is that really going to make a difference to any individual crab? To the species? Probably not, I think. And yet, it could.

* * *

Animal studies scholars address the role of interactions and intersubjective exchanges between human and animals in social worlds and within their research processes.27 This scholarship and research in critical animal studies wrestles with the human tendency toward anthropocentrism in our thinking about and acting toward the world. Anthropocentrism is a belief system or way of thinking that regards humans as the center to all existence above all other living things. This perspective slips into thinking of nonhuman beings as inferior to humans, and as such, anthropocentrism is akin to racism, sexism, and classism. In other words, anthropocentric thinking requires the same stratified value judgments as when we see certain types of people (men, white people, able-bodied people) as more worthy than other people (women, people of color, or people with disabilities). Critical animal studies implores us to challenge our anthropocentric worldviews through our scholarship and practices.

Much of the important work in this focuses on pets like dogs and cats, the mammalian domestic companion animals with which we have intimate encounters.28 Moving from mammals, the anthropologist Hugh Raffles’s Insectopedia explores our close encounters with insects and uncovers the vast continuum of insect/human entanglements—from being assaulted by malarial mosquitoes in the Amazon to betting on Chinese cricket fights.29 In Catch and Release, I am a sociologist seeking to understand the experiences of horseshoe crabs. Even though I can’t completely set aside my human standpoint, I can attempt to engage with “crabness” and to dwell in the strangeness of the ontology of another species. And while my attempts ultimately don’t result in my being a crab, the work of trying does shift my consciousness, fostering a more attentive collaborator. At the same time, I reckon with my own and others’ epistemological productions—the suppositions of what we know about the crab. Through this I try to begin to move further away from the socially constructed distinctions between human and animal, knowing and being, and the nature/culture binary. In many ways the title of this book, Catch and Release, refers to this larger project of simultaneously catching and releasing actual crabs and also the feeling of being always on the cusp of apprehension of another species. I am continuously cycling through catching, apprehending or knowing certain facts about horseshoe crabs, and then releasing, letting go, or refining those facts through the ontological experience of being with the crabs.

Engaging in the intersections between humans and crabs and entertaining the possibility of an ontology of other objects—sand, beaches, gravel, water, surgical tubing—enables us to reposition them through de-centering ourselves. This multispecies ethnography expands upon the methodology I developed with Mary Kosut in Buzz: Urban Beekeeping and the Power of the Bee. Multispecies ethnography is a new genre and mode of anthropological research seeking to bring “organisms whose lives and deaths are linked to human social worlds” closer into focus as living beings, rather than simply relegating them to “part of the landscape, as food for humans, (or) as symbols.”30

Elsewhere Kosut and I have proposed an ethics of intraspecies mindfulness, a concept that was further developed in our shared scholarship.31 Intraspecies mindfulness is a practice of speculation about nonhuman species that strives to resist anthropomorphic reflections or at least be aware of them as a means of empathetic understanding. It is an attempt at getting at, and with, another species from inside the relationship with that species instead of from a top-down relationship of difference. In our practices with bees, Kosut and I used our own sensory tools of seeing, hearing, touching, tasting, and smelling bees—their bodies, their habitats, and their products. Getting with the bee meant acquiring new modes of embodied attention and awareness. Getting at the bee has also meant that we must confront the reality that the human species is always and everywhere enmeshed with the bees—they pollinate our food, changing our agricultural landscape, and we transform their habitats (and our own).

Our creation of the term and practice of intraspecies mindfulness is drawn from the work of Karen Barad.32 Again key to my work is also the term intraaction, in which materials come into being through the mutual constitution of entangled agencies. This approach requires that as fieldworkers we interrupt our tendency to think of animals as the object of study and that we resist thinking of ourselves, or the animal handlers (in this case, scientists and conservationists) as static, bounded, and permanently fixed entities. Instead, we need to see all—ourselves, crabs, scientists, and other objects—as bodies that are in the world and whose boundaries are created but also porous. These boundaries are managed through entanglements and conflicts. In fieldwork, I worked to treat each experience as an opportunity to witness this emergence of intraaction. Each moment was a chance to see the crabs and humans in intraaction, constituting each other in their own humanness and crabness.

In this research project, I not only perform a study of how scientists and crabs make each other but also a study of how I, as an examiner of scientists, make something of this studying of crabs. It is recursive in that I am reflecting on my own knowledge production as different from, and yet entangled in, the production practices of the scientists whom I accompany. Catch and Release is complexly layered in interpretation—my particular involvement in multispecies ethnography (in which I practice science very much like a scientist proper) gives me a unique advantage, perspective, distance. and proximity. I am an ethnographer sociologist apprehending and communing with crabs, and I am a scientific practitioner investigating how scientists work with crabs. Simultaneously, as each chapter reveals, I am an urban commuter adding emissions to the earth with a scandalous diesel Volkswagen automobile. I’m a mother bringing my sometimes-reluctant daughters on several fieldwork trips, cajoling them with promises of ice cream after swimming with crabs on hot Brooklyn days (in dubious urban waters).33 There are many layers to the research project: research on human-and-crab, and on scientist-and-crab, and on sociologist-scientist-crab, and on driver-human-sociologist-scientists-crab-water-innertube-children.

My 4 years of fieldwork with horseshoe crabs and the community of humans they attract gives me the foundation for engagement in understanding the ways humans and crabs interact, intraact, and intersect. Through interviews with an international array of scientists, conservationists, pharmaceutical executives, fishermen, students, and beachcombers, I examine the ways humans come to use and know crabs. Also balancing intraspecies mindfulness with scientific data collection, I have spent hours and hours on beaches (primarily in New York City) engaging with crabs, conducting egg density surveys, coring the beach, censusing crab populations, evaluating shell quality, measuring carapace size, surveying shells for numbers and types of fouling organisms, counting juveniles, and measuring sediments. I have attended international meetings of crab-monitoring and endangered species designation workshops. The traditional methods of qualitative interviews and ethnographic fieldwork are combined with physical and emotional engagement with thousands of horseshoe crabs.

Layout of the Book

Each chapter of this book takes up a different theoretical framing and geographical location of horseshoe crabs.

As many scientists attest, we are in the midst of the sixth mass extinction.34 In order for the rate of extinction to be deemed a significant ecological crisis, scientists use the fossil record to calculate the changes in biodiversity on the planet caused by meteorological and geological events such as asteroids hitting the Earth and volcanic eruptions. In chapter 2, “Endangered,” I interpret the evaluation of the species health of the horseshoe crab while simultaneously interrogating the debates of framing our current time period as the Anthropocene, the epoch that attributes massive climate change and species decline to human activities, not just to nonhuman events.

Every 4 years the International Workshop on the Science and Conservation of the Horseshoe Crab is held for scientists and educators to exchange information about the species. In 2015, I participated in this conference in Sasebo, Japan, the largest to date, with over 130 presenters from Japan, the United States, Hong Kong, Taiwan, China, Malaysia, Singapore, India, the Philippines, Mexico, Denmark, and Poland. One of the main reasons for these meetings, in addition to the scientific exchange of data, is to establish protocols for classifying horseshoe crabs on the scales of extinction. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN)—a team of concerned humans, including marine biologists, microbiologists, ecologists, ecotoxicologists, paleontologists, and conservationists—is the oldest global conservation organization. A primary objective of its work is to support biodiversity and create species specialist groups for vulnerable organisms.

The IUCN Horseshoe Crab Specialist Group formed to collect data to evaluate the conservation status of the four living species of horseshoe crabs for placement on the IUCN Red List. The Red List is IUCN’s comprehensive evaluation of global plant, fungi, and animal species and their relative threat of extinction. The procedure for assessing the risk of species extinction involves monitoring and compiling empirical data. The Red List categories are Extinct, Extinct in the Wild, Critically Endangered, Endangered, Vulnerable, Near Threatened, Least Concern, Data Deficient, and Not Evaluated. Currently, the North American horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus is listed as Vulnerable. The three Asian horseshoe crab species are listed as Data Deficient, which means that they have not been critically reviewed. Red Listing an organism doesn’t guarantee protection, but the Red List status informs policy makers of the situation and may add greater power to conservation efforts.

“Endangered” takes up the meta-analysis of humans measuring species decline. How is it that particular species becomes a concern for humans? It has become somewhat of a given that humans care about charismatic megafauna, those large mammals of popular appeal—think of cuddly stuffed animals cementing our lifelong relationship with animals we’ll never meet in the wild. But how do ugly, weird, spiny, or spiky animals come to matter? How do we make them count? The literary critic Ursula Heise cogently argues that when humans “discover” endangerment, it is first and foremost through a process of human storytelling. These stories frame our perception of what animals come to matter and why and guide scientific techniques and measurements.35 My book is an attempt to understand the story of how horseshoe crabs have come to be understood and designated as Vulnerable.

The sexual reproduction of horseshoe crabs is the basis of chapter 3, “Amplexed.” Horseshoe crabs do not successfully breed in captivity. Therefore researchers attempt to collect as much data on crabs in the wild and establish laboratory-based experiments in order to examine the their reproductive cycle. Horseshoe crab reproduction, also called spawning, is an event that excites humans—field biologists, other professionals, and laypeople. In fact, in the Northeast United States in May and June, conservation groups and individuals plan spawning field trips to visit nesting habitat and watch the crabs come to shore in amplexed pairs. When pairs of male and female horseshoe crabs reproduce, they do so by amplexing, or clasping in a “copulatory embrace.” This chapter examines the ways humans study, present, and represent these reproductive events.

I use my own participation in, and analysis of, mate choice experiments, horseshoe crab spawning field biology data collection, and juvenile counts as data in this chapter. I analyze interviews with horseshoe crab reproduction scientists to understand how they construct normative reproductive practices despite outlier data.

Turning to blood, chapter 4, “Bled,” explores the dangerous world of endotoxins, molecules that form on the external membrane of Gram-negative bacteria like E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella, and many others. Endotoxins are pyrogens, fever-causing agents that are heat stable (these toxins aren’t destroyed when heated). In the right dose, endotoxins are lethal to humans and livestock and companion animals, and they are ubiquitous. Horseshoe crab blood keeps us safe from these endotoxins, but at a cost. This chapter examines the growing tensions between the field biologists and the conservationists and the pharmaceutical companies and medical professionals in how horseshoe crab blood is harvested and used. It explores the issues surrounding the amoebocyte lysate tests that are used to detect the presence of endotoxins on both local and global scales. North American horseshoe crab blood is used for the Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL) test, and the blood of Asian horseshoe crab species is used for the Tachypleus amoebocyte lysate (TAL) test. Testing the safety of biomedical devices that go inside the human body requires the LAL test. Even though there is a synthetic alternative, it is bureaucratically untenable. Despite the fact that bloodletting for the LAL test causes stress to individual crabs and the species as a whole, human discourse narrates it as harmless and safe.

Humans create a safer world and generate profit from horseshoe crab blood. Beginning with an analysis of the discursive and material scaffolding to affirm crab bleeding as a donation, I explain the stakes in how humans characterize the extraction of blood from another species even when our own intraspecies donation is not as simple as we might believe. Next I explain the biomedical significance of the product generated from horseshoe crab blood, Limulus amoebocyte lysate, and how humans have attempted to protect themselves from a world teeming with invisible bacteria through the biopharmaceutical manipulation of horseshoe crab blood. I consider the geopolitical terrain of biopharmaceutical marketing, human population dynamics, and global horseshoe crab endangerment and describe how the crabs (and their valuable blood) are potentially becoming a contested resource between nations and continents. I end with a discussion of how, despite the synthetic alternative to LAL being available, there is no pragmatic, political, or economic will to switch to this product, thus ensuring the continued bleeding of horseshoe crabs. Ultimately, this chapter traces how human and nonhuman matters bleed into one another, whereby nonhuman animals fortify our bodies in anxious times of disease transmission and our treatment of nonhuman animals inflame, fortify, nuance, or trouble the intrahuman matters of worthiness, global stratification, and commerce. The pharmaceutical industry represents an intensification of the human-crab relationship. It is in a sense a speedup of globalization and biomedicalization in which tensions between conservationists and biotech companies weave an interesting story.

Finally, chapter 5, “Enmeshed,” considers habitat and space as meaningful, albeit in different ways, to horseshoe crabs and humans. Using Timothy Morton’s notion of hyperobjects—global warming, in this instance—as a backdrop in this chapter,36 I explain how site fidelity and reclamation projects increase the vulnerabilities of both species. As access to shoreline and coastal habitats are under threat, both crabs and humans must adapt to changing environmental stressors.

Site fidelity refers to horseshoe crabs remaining faithful to, and to returning to, their specific spawning ground year after year to breed. Their site fidelity both increases their vulnerability to harvesting and makes them an excellent species for field biologists to study—you know where to find them. Musing on the term and behavior of site fidelity, I describe the ecological land/seascapes of horseshoe and human habitats in decline and how horseshoe crabs become a sentinel species for human interpretation of ecological health.

This chapter also examines the practice of reclamation, which refers to human engineering to change lakes, rivers, oceanfront, or marshes into usable land. Habitat destruction through reclamation projects such as beach armament and embankment destroy geomorphical continuity. For example, in Japan more than half of Japanese beaches are covered by artificial structures to address sea-level rise, to fortify shorelines for tsunami protection, or to extend the coastline outward and backfill to create industrial, agricultural, or residential land. Globally by 2025, it is predicted that 75% of all human populations will live at the coastline. This massive concentration of population at the coast as sea levels rise creates conditions for hot, sour, and breathless bodies of water. Algal blooms will continue to suffocate seas, with hypoxia and acidification of the oceans, combined with runoff of heavy metals and pesticides into the sea, creating conditions that are toxic to horseshoe crabs. According to Mattei, it isn’t egg predation that is killing urban horseshoe crab eggs—it is contamination: Eggs are poisoned by lead and other pollutants. Juvenile crabs also suffer from lack of food sources owing to contamination. Horseshoe crabs’ long maturation process means that a single “missed” generation could have massive population effects. Creating a “living shoreline,” or urban estuaries, is one possible solution that I discuss in this chapter.

In the conclusion, “From the Sea,” I speculate on the future of the horseshoe crab. I also consider its remarkable ability to survive as a species for millions of years, and I make a case for its continued persistence. Furthermore, I also suggest that the sentinel data that we are generating from studies of horseshoe crabs and habitat destruction might actually indicate that it is humans who have more to fear from our engineering of the shorelines than horseshoe crabs. I end with a reminder of the themes that were explored throughout this book.

Over my lifetime, and more intensely and carefully over the last 4 years, I’ve probably handled thousands of horseshoe crabs. I’ve dug for their eggs, flipped them over, and followed them in the shallow surf, trying to keep pace with them as they glide out to sea. I love the feeling of holding active older crabs; as I slip my hands underneath their bodies, they grab onto me as if they are hugging my hands, and I feel that we are physically connecting. Their gripping is reassuring to me. And as I demonstrate in this book, I’m also implicated (as are you) in their capture, relocation, and bloodletting. I feel responsible to represent these nonhuman others, unlike other research subjects or informants, in ways that garner compassion, concern, and action from humans. At the same time, I must admit a certain quality of relief in that these subjects don’t talk back. Both literally and figuratively, I hold the crabs and their stories in my hands. They can’t talk back to me in a way that I can completely comprehend, but I must muster all my skills of observation and interpretation, as Carl Shuster suggests, to understand both the material and symbolic lives of horseshoe crabs as well as our becoming with them.