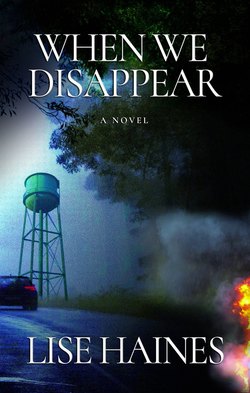

Читать книгу When We Disappear - Lise Haines - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Mona

ОглавлениеHe shut off our alarm clocks, loaded his car, eased the hand brake out, and backed down the drive without turning the engine over. Richard, my father, was probably in Indiana by now. He had tossed his house keys on the counter as if he wouldn’t be back. An envelope was propped on the kitchen table with a letter written to Liz, my mother.

“He didn’t wake you? To say goodbye?” I looked through the blinds to see for myself that his car was gone.

His coffee cup stained the table, sugar sprinkled across it, wet spoon stuck back in the box.

“No, I guess he …” She stopped when she opened the letter and began to read.

Next to the envelope was a coffee-table book, National Monuments Across America, filled with glossy color prints of Yosemite, Bryce, the Giant Sequoias, Niagara Falls. There were several Ansel Adams’ black-and-whites. I used to pore over that book as if I were looking at shrines. We had talked about visiting monuments in one long vacation when I was young. He left the book open, weighing down the pages with our green carnival-glass salt and pepper shakers. Maybe that’s how he was able to leave, thinking he’d return before long and someone would take that trip with him. My mother and I looked at the photograph of a herd of bison running across both pages, from left to right up to the edge of the paper like the edge of a cliff.

I tried to read the letter over her shoulder but she pulled it to her chest. Mom was in her mid-forties then, ran most days, drank little, never smoked. Now there were lines around her mouth I hadn’t noticed before. Her eyes appeared smaller, as if they had sunk into her skull overnight.

The year was 2007. I was seventeen and Lola was three. Our plan had been to get up in time to see him off. She would have been fast asleep in Mom’s arms at that hour. No one slept as soundly as Lola. Mom would have said goodbye for Lola, swaying her from side to side on her hip. I would have stood there for my mother’s sake.

My eyes began to water, and the bison looked smaller, more like lemmings.

Folding the letter, she put it in the pocket of her robe. “He’ll call when he gets to New Jersey.”

“You aren’t going to tell me what he said?” My voice began to strain, as if I had started running to catch up with his car.

“He had a hard time saying goodbye.”

“You’ll have to tell Lola.”

“You aren’t breathing right,” she said.

“I’m fine.”

“Hold on.”

We had a drawer stacked with lunch bags.

When I was breathing in and out, filling and collapsing one of the bags, she said, “We’ll go to the Art Institute today. We have a month left on our membership.”

This was her solution to most things: lose yourself in art. But I couldn’t afford to take off because my father had taken off. I was in high school, finishing the first semester of my senior year. I had three finals coming up.

“We’ll show Lola the Thorne Rooms,” she went on, in her spirit of repair.

Each of the museum’s miniature rooms was decorated in a different period and style from the thirteenth century to the 1930s, the furnishings on a one-inch to one-foot scale. Everything was perfect, yet no one lived in any of those rooms. Or from the other side, the curator’s side, everyone who peered inside was a giant and all of their imperfections showed. Mom had taken me there many times when I was Lola’s age.

Once I was breathing normally, I said, “Maybe next weekend.”

My mother held me and kissed my cheek. “Come upstairs if you need me.”

Then she went off to turn on the shower in the master bath. Here she would break down. I walked in on her doing this once. She sat on the lid of the toilet, weeping under the sound of the shower, as if none of us would find out.

While I listened to the water run upstairs, I wondered if things might have been different if I had woken early and found him at the kitchen table, pen in hand, about to sign his name to the bottom of that letter. Maybe he would have gotten past the sadness of leaving her to leave her the right way.

Though I had stopped listening to his stories years ago, I would have listened to this one, even pulling a chair up to the table and turning off my phone. He would have started with a man taking off from the people he loved in difficult times, using great care in the way he invented this man, the look in his eyes, his rumpled clothes. Dad was an impeccable dresser then, so this last detail would have been his effort to set himself apart from the man he conjured. After a while Richard would have reached into his suit pocket to give me the handkerchief that was laundered and pressed for the road, trying to make me feel that things were going to be all right. This idea would have lingered in the light penetrating the blinds. But once he was gone, it would have dropped to the linoleum and left a mark as if a heavy jar had landed there.

The thing I couldn’t say to my mother was this: Lola was too little to be left, and Mom wasn’t fragile exactly—I never saw her as someone who would crack—but she was unprepared. And I really had no idea what he expected me to do about any of this.

I listened to the familiar thump in the pipes as the water was shut off upstairs. I went into my room. There I curled up and fell back to sleep, the only place where I knew how to cry openly.

After he left, we began to move around the house like dogs trying to settle, each of us showing the tension. Yet Mom continued to make him sound like the mail carrier that comes through. “I don’t know a better man than your father,” she said too often. There was a feeling that stood behind or off to the side of those declarations, something about his departure I couldn’t name.

Lola began to hide things under her bed. Popsicle molds, favorite toys and clothes, small boxes of cereal, light bulbs, cotton balls, and photographs of him. She clung to us in ways she hadn’t before. And Mom thought too much about the dangers that might befall us if we weren’t vigilant, now that we were living alone. She watched an endless string of safety demonstrations online and wanted to reenact some of them with us. At least Lola was willing. I began sleepwalking again, and when I gravitated to the neighbors’ dry fountain next door where they found me curled up in my pajamas, Mom worried about me walking into the street, and she worried about me being out in the cold, and she worried about the upcoming summer when the fountain would be full. She got her drill bits out and installed chain locks high up on the front and back doors.

I knew his going wasn’t only about a job in New Jersey. She made a point of telling me he sent money every two weeks without fail. Though she never broke this down, the money was never enough. Once a week she talked with him by phone. I was convinced they were pretending at something. Mostly she talked to him deep in her room, sometimes in her closet.

When she emerged, Lola would get on. She could be very chatty, and Mom often helped her to say goodbye and let go of the receiver so Mom could budget and call next week. Once, Lola didn’t like this idea at all and pulled so fiercely to keep the phone, it sprang back and hit her in the forehead. Mom sat for a long time with her, holding ice against a swelling bump, whispering and rocking her, and telling Lola everything was going to be all right. I described the scene to Dad because Mom insisted I keep him on the line—until she realized this was only making Lola cry harder.

Lola got phone shy after that, so he started sending her postcards. They came with pictures of fairgrounds or restaurants or caves—the kind of free cards advertisers give out where he found enough room to write around the pitch. Mom helped her start a scrapbook with the cancellation marks and smudged town names.

One of his letters arrived from New Jersey. That was his way, to send letters in blue ink. He didn’t like the idea of email or texting. He laughed at social media, made stupid jokes about Skyping. I was about to throw the letter in Mom’s bill pile when I realized it was addressed to me. It took me two days to open it.

Dear Mona,

Do you remember when you were a little thing like Lola, and Mom gave you her old Brownie camera? You wouldn’t let anyone show you how to work it and before long there were dozens of black-and-white photos of shoes and ceilings and noses. She pulled a box down from her closet and searched around and handed you one particular picture she had taken and said, “I could show you how to put a ghost in a photograph.” Your first lesson was on double exposures.

I’ve been thinking we’re all double exposures in a way, that there are things we sometimes miss in the layers. What am I trying to say? I know things haven’t been easy between us for some time. But I was wondering if we couldn’t get a fresh start. Maybe if we wrote once a week for a while and talked a little on paper I could get to know you better. I’ll begin with this letter and hope you drop me something, even a sentence. I know you’re busy.

Next letter I’ll tell you a story about your Great Uncle Sorohan, who could see through the layers, right to the bottom of your soul and a couple of ticks further.

Please take care of your mother and Lola, and know that I love you.

Dad

In my whole life I hadn’t taken a single double exposure.

I went out behind the garage, where Mom kept her cleaned-out oil drums for scrap metal. I set a small fire in one of them. I opened a photo album I had started years ago. There was the picture where he was guiding me on my first two-wheeler, one at the beach in his swim trunks, one standing by a new car. I took them out of their sleeves one by one and dropped them into the fire and watched them bubble and curl at the edges.

A few days later I learned that he hadn’t received his commissions at his new job. Mom increased her part-time phone sales—pushing her real work, her giant sculptures, off to the evenings, sometimes late into the night. She had only taken that job as a stopgap right before Dad left, while her résumés and applications circulated in a shrinking job market. Now that selling ad space was the big thing in her day, Lola and I weren’t supposed to pick up the landline. If she had to go out or use the bathroom during her shift, she called another salesperson by dialing a code into the phone. I recall one conversation in particular when Mom switched to speakerphone so she could fold laundry before starting dinner. She hugged Lola, who was lingering in her arms, and handed me the shoe-tying board so we could continue the lesson they had started between calls. Lola quickly pulled it out of my hands, saying, “I can do it myself.”

“Okay, I think we’re all set. I’ll repeat the message,” Mom said after a while. She rolled a pair of Lola’s socks while she reviewed her notes. She had learned early on that if she got the message wrong, it came out of her pay. In a flat voice, at a good volume, she said, “Quote: We met in the best of times, you made it the worst of times. You’re a total witch, Debbie, and I hope you and your whole family go to hell. End quote. You want this to appear in Friday’s paper, in the Personal Regrets column in twelve-point type, inside a bold box, to run for six days. Wednesday will be the last day it will appear unless you call in on Tuesday by noon to extend the ad.”

“I didn’t say witch. Who says witch?” The guy’s voice boomed out of the speaker. “That’s bitch, bitch. Bitch with a capital B.”

My mother stood up, and a dozen pairs of neatly tucked socks left her lap and bounced and rolled across the floor. She signaled to cover Lola’s ears while she struggled to turn off the speakerphone. But Lola broke away and chased the socks, kicking them here and there as I pursued her.

“The newspaper has a policy against—” Mom began.

“Just tell me what it’s going to cost to get the fucking message I want in the paper.”

Lola stopped, and her eyes got wide. She was alert to the tone or the word or both.

“Even if you understood Dickens or the French Revolution or why they stormed the Bastille …” Mom began.

The guy hung up. With intense jabs Mom punched in the code on her phone to signal for another customer service agent to pick up. Then she looked at me and said, “God help me,” and went off to the downstairs bathroom to soak her face with a hot, dripping washcloth over the sink.

Mom introduced her latest safety demonstration when Lola was away at an overnight. I was watching The Giant Gila Monster on TV, getting ready to go out. Mom called me into the kitchen. She stood by the stove and handed me a box of wooden matches. She wanted me to start a stove fire so she could show me how to put one out.

Glancing into the living room, where the TV was still lit up, she asked, “What are you watching?”

“It’s about a big lizard that terrifies a town in Texas.”

Mom began to say something, but maybe she thought better of it. She pulled a cast iron pan off its hook, got a high flame going, and when the pan was hot, she dropped a tablespoon of bacon grease into the center and then another. We watched the fat turn transparent with small bits of black in it. “Once the grease starts to smoke,” she said, “I’ll give you the signal.”

“I have to finish getting ready,” I said.

“If you’re alone with Lola, you need to know how to do this.”

I had started to live more out of the house than in, so my mother liked to snag me whenever I landed. The thing was, I had made hundreds of meals for Lola. They were never complicated. Lola liked pasta, macaroni and cheese, apple slices, carrot sticks. Mom just wanted the world buttoned down because none of it was anymore. Sometimes it seemed easier to go along.

Taking a match out of the box, I held the red tip against the striker.

“Ready?” she said. She was in a heightened state now, apron sash tight, straight dark hair loose around her shoulders, her eyes large and bright. She put her hand on the paper sack on the table like an actor in a public service commercial. “In case you have to put a fire out while you’re cooking, it’s always good to have salt at the ready.”

“Got it,” I said. My mother began to tug at the white string at the top of the sack. I saw that everyone was already at the sock hop and the Giant Gila Monster was headed their way.

I didn’t see that the string wouldn’t budge. She told me this later.

I did, however, clearly hear my mother say, Now.

She meant Now as in Now … if the bag won’t open, you might need to get a pair of scissors. But I was sure I heard the signal, so I lit the match and it left my hand and arced toward the pan at the same moment she turned away from the stove to look for those scissors, her hair flying out in a wide circle.

I saw a blue flame surround her head like a crown of stars, and I heard her scream the same terrifying scream a wild peacock will make out in the dark. I had a great uncle who lived near wild peacocks, and as the fire danced along my mother’s head and I stood there paralyzed, I heard that exact sound leave her throat.

In a sudden flood of safety memories, I knew to grab a jacket off the back of a chair and cover her head, holding it there until the fire was out, holding my mother until the flames were gone.

We took a taxi to the hospital because she was afraid of the cost of the ambulance. I was the one who cried, apologizing in a soft whisper, thinking her ears had been burned. She seemed to be holding her breath while she patted my leg to quiet me.

Once the examination was done, the ER doctor shut his eyes for a moment as if he were pulling up thoughts from a dark cave. He said my mother was a lucky woman. “You’ll have some scarring on the back of your scalp,” the doctor said, opening his eyes again and indicating places around her head while I held the hand mirror. “But much of your hair will grow back and more or less cover those places.”

My mother flinched, and he said, “You might have been facing the stove,” as if he thought she would do this again.

That’s when I realized how easy it is to burn the house to the ground with all the people in it because you’re trying so hard to prevent disaster.

On the ride home she asked me not to tell my father, like we should be worried about protecting him.

For weeks afterward a vision of that crown lit up my mind, sometimes during the day but often in the middle of the night. It was the pain I felt over what had happened, of course, but I was sure I had also seen a drawing or painting of that halo. When I searched online, I found Our Lady of the Apocalypse.

I recalled that a photographer friend of Mom’s had given her a coffee table book filled with shots of Virgin Mary statuary. Locating it in the shelves of art books, I read that he had spent months traveling around the States following a path of closing parishes. He would set up his camera the day before a church was going down and shoot those ethereal figures, many already pulled from their pedestals. Some had crowns on their heads, some with stars. There were hundreds, maybe thousands of abandoned Marys with missing noses and arms and heads. On her worst days, I think that was exactly how Mom saw herself after my father took off.

I went begging and Geary, my old photo teacher, hired me to help in his darkroom. It was my job to set up lighting and backdrops in the studio, order supplies, catalog, and make deliveries around the city. He and his wife, Lettie, had only one car, so this often meant public transportation.

One delivery was to a fashion photographer on the near west side named Nitro. He did some of his own fine art prints but relied heavily on Geary for the fashion stuff. I was supposed to call if Nitro gave me any shit. Before I could find out what Geary meant he got a call from his wife. So I left and rode the L and when I leaned my head against the train window, I heard the wheels on the tracks sounding: Nitro. Glycerin. Nitro. Glycerin.

A guy in his late thirties, wearing jeans and a white button down, met me at the door to his loft. He had two controllers in his hands. Halo was on a big monitor across from his couch. Looking a little embarrassed, he said, “Just setting up some new equipment.”

I held out the two black photo boxes, one stacked on top of the other.

“You’re from Geary’s?” he asked, making a study of my face.

I looked down at the boxes, Geary’s studio name and address typed right there, and looked back at him.

“Halo?” he asked, taking the boxes.

I shrugged and he handed me a controller.

He wasn’t very good at it. I had to keep explaining how the controls worked. Or he was good at it and just wanted to sit close to me on his old leather couch. He put his hand on my knee and I took it off. After I beat him at the game too many times I got up and looked around.

Nitro had photographs of his parents on one wall, their faces blown up so big you could drift into them and feel like a speck, like a bug in their eyelashes. Nothing flattered, nothing pulled back. They reminded me a little of Mehdi Bouqua’s stuff, a street photographer working out of LA. On another wall Nitro had seven shots of young gang members in the city. He used backlight and fill, and somehow this made them appear as if they were about to ascend into the sky in a threatening yet childlike moment. They sat on beat-up playground equipment in a city park and I realized what he was after. “You like William Blake, his artwork,” I said.

He looked at me as if to say, What kind of creature are you? I could hear that word creature in his thoughts. “Yes, very much. Pity. I think that’s my favorite. Do you know that one?”

“I like the really blue version at the Tate,” I said. Not that I had been to the Tate but my mother had an art book of Blake’s work with four versions of Pity compared side by side, and I tended to remember things like that.

“You want to stay for dinner?” he asked.

“I should get back.” Looking at some of the fashion work spread out on a long table, I asked, “You date any of them?”

“Used to,” he admitted.

“I’d never get attached to you the way they did,” I said.

He laughed and asked, “Why’s that?”

“Because I don’t give a shit about immortality.”

“Stay for dinner,” he said. “We could talk about your dreams.” He nursed some kind of tenderness as he coaxed. Dream analysis was a party trick Nitro performed. When I questioned his ability to make interpretations, he said his mother was a psychoanalyst.

I got my jacket on and wrapped my wool scarf around my neck, and in an odd moment I let him knot it and throw one end over my shoulder as if he were dressing me for a shoot. He came very close like he had an impulse to kiss me but he pulled back at the last moment, which told me he was probably used to this kind of seduction. I took off and got home in time to read Lola a bedtime story.

I made another delivery a week later and when he opened the door I saw cheese and bread and wine arranged with a bowl of fresh dates on his coffee table.

Each visit got a little more elaborate: the four-course meals, the special selected movies, hookahs with full bowls.

I began to go over there once a week to deliver myself.

Nitro and I played a lot of Call of Duty after I got him started. We racked up kills and we began to photograph each other clothed and naked and standing in front of a large mirror embedded in a piece of architectural salvage—from a convent bathroom or an Irish bar—he couldn’t remember. We stretched out on his bed and along his kitchen counters and dining table and sink and bathroom floor and fire escape and in front of his giant windows at night and we had unadulterated sex.

But that’s not why I fell for Nitro. It was watching him burn and dodge in the darkroom, the seconds of exposure, the way he cropped an image. Sometimes I sat on a stool to watch and sometimes I put my head against his shoulder for a minute, and he would tell me how long to make the exposure, and we became inseparable until the timer went off.

I guess I amused him at first. There was a lot he didn’t ask me directly, so I photographed what I thought was a lack of questions in his face and he photographed the questions in mine. He loaned me cameras and tripods. We smoked too much pot and he bought me eye drops and mints so my mother wouldn’t quiz me when I got home. He asked what I liked in my omelets. We talked about lighting techniques. His loft became that place where I could say anything, do anything. That’s how it worked.

He had a four-year-old son and an ex-wife. A model. They lived in France and Nitro saw his boy three or four times a year. He said he’d be going over there soon. I waited for him to beg me to go. And then I saw two tickets, one his, one with a woman’s name. I assumed she was one of the flawless women.

I cried on the way to the L going home, but I figured that was something about modern love. It wasn’t about him. It really had nothing to do with him.

He told me many times he loved the way I looked: unaltered, pure, almost virginal. But after he took off on his trip, I began to think about legs and arms and bracelets. About jackets, perfumes, stockings, the things he caught with his lens.

I pushed my way into Neiman Marcus, just taking a cut-through in the mall at first, until I saw this blouse. I was sure he would like it. I tried it on in the dressing room and cut out the device on the bottom hem that sets off the store alarm with the manicure scissors in my makeup bag. It was cream-colored silk with a pointed collar that felt right to the touch. I was surprised at how easily I walked out of that store and how I enjoyed the breathlessness. At home I cut off the bottom and used my mother’s sewing machine to rehem it.

The day after his return he looked at the delicate custom buttons open to my waist, smiled, and said, “Sabrina.” Then he had to explain that this wasn’t about another girl. He was thinking about an old movie in which the chauffeur’s daughter, played by Audrey Hepburn, suddenly becomes a woman out of Paris Vogue. I was pleased and didn’t care that in his hurry the fabric ripped where I had stitched it. Something had changed.

I began to clip the kind of jewelry that sits out on counters. I knew it would be easy to take a jacket or scarf holding a place in a movie theater or coffee shop, but I understood his tastes, and this meant small acquisitions from particular stores. I walked away in a handsome pair of heels, leaving behind socks and beat-up footwear on a showroom floor one afternoon.

“You have to figure this out,” he said later that day when he realized what I was doing. He was staring at my heels. I pulled away and sat up in bed. Neither of us had had the patience for the buckles. “There’s someone you’re trying to rattle.”

Rolling onto his side, Nitro lit a cigarette and I watched the smoke drift, looking for that point where it disappeared. The ceilings were twenty feet high and the late afternoon light poured in through the long sash windows. His loft was part of a converted candy factory taken over by an artists’ cooperative. There were marks where giant copper vats had been strapped to the floors.

“Rattle?” I said.

“By getting caught eventually.” He picked up my phone and began to flip through my photos. I tried to grab it away, but he got playful. I decided not to make a deal out of it so he’d stop. He paused on a shot of my parents together at a restaurant. I had used a high intensity flash so they looked half there and kind of shocked. “Nice framing,” he said. “So your mom thinks he’ll be back?”

I don’t know why this was sitting in his foreground now. His cheeks were pitted and this made him look rough at times. He told me once that he couldn’t stop scratching when he had chicken pox as a kid.

“She’s waiting for him, that’s all I know.”

“They don’t do well,” Nitro said, lost in his own meditations. Then he looked over at me and began to blow smoke rings as if I needed entertainment.

“‘They’? Who doesn’t do well?” I asked.

“Left women. You know, when children are involved.”

I felt my blood pick up pace. “He was out of work for a long time,” I said. “And then this job turned up in New Jersey. I wouldn’t call that leaving her.”

“You don’t have to go to New Jersey to sell insurance. Besides, if this was strictly about a job, you wouldn’t look troubled.”

“You think I’m a child,” I said and pushed into his stomach with my elbow to reach the bedside table. I pulled the last cigarette from his pack and grabbed the lighter.

His father, who had died of lung cancer, looked down at me like a dark cloud from the wall. I lit up, inhaled, and found out how light my head became on tobacco.

“Maybe you’re thinking about your son, about the way you left him,” I said.

“But I didn’t,” he said, clearly pained now. “She left me and took off for France. And in the French courts there was little I could do.”

“Who did you take with you to Paris this time?”

“An old friend, a photographer.”

“Someone you see from time to time?”

“You’re making too much of this.”

“What does she look like?”

He hesitated long enough to realize I’d persist. There were some pictures on his phone. She seemed rather plain, wore almost no makeup. Certainly there was nothing about her clothes to draw him in.

“What type of photography? Show me.”

“You aren’t going to let this go, are you?” he said. He got out of bed and took my hand. I was a little wobbly in the heels. He guided me over to a set of large flat drawers. She had her own drawer. I didn’t. I didn’t have a drawer. She was a street photographer. I wouldn’t say she was better than me, just different. It almost looked as if she had posed her subjects, certainly they were standing still in their settings, and she took her time to frame things. I was more abrupt, more into movement, light, and emotion. I didn’t mind that someone was lopped off or caught at a funny angle. I liked to shoot people before they had time to think, to respond.

She was thirty-five, he told me when I asked. They had seen each other on and off for years. But things weren’t like that anymore, he said. I wasn’t sure I believed him.

I closed the drawer and worked on the buckles and left the stolen heels by the door. I got dressed, and all the time he watched me. I turned my phone on again and began to flip through my mother’s messages. There were seven.

“You understand they arrest you if you get caught,” he said, circling back to my small larcenies, pushing away from his.

“I’ve already got a mother,” I said and held up the phone with her texts stacked in a heap.

“If you need money, all you have to do is let me know.”

But I was already working on other ideas. Not clothes.

Pushing in, he offered to give me a ride back to Evanston. I took the L.

Of course it had to be that night when the bill went online breaking things down in preparation for my first year of college. I didn’t tell my mother and called a financial aid officer the next day.

“Things have changed,” I said.

The woman waited as I told her my father had moved away and wasn’t sending much money before she launched in. Maybe the AC units were broken in her office that day or she was working from home and a cat was gnawing at her toes or she just didn’t like the sound of my voice. Whatever it was, she got merciless about the college’s funding distribution practices, the limits of federal aid, how far from extended deadlines I had drifted, the effort they had put in to arrive at a good package for me, as if her entire office had traveled for months in a desolate country to reach me. Finally, she suggested I consider delaying admission for a year. I could reapply for aid next winter. “You might need to submit an updated portfolio,” she said, topping off my empty glass.

“That can’t be right,” I said.

“You’ll want to check with the department.”

“There’s a small fortune in photographic paper, chemicals, the time it took to—”

“I just wanted to give you a heads-up,” she said in her monotone.

“Your head’s up your ass,” I said and dropped the phone into its charger.

A few days later, when Mom asked for my password to get on the site to see where things stood, I said I was taking a gap year. She pushed back hard, but when I said I wouldn’t budge, that I wanted to work at Geary’s full time and save up money, I don’t know, maybe she began to accept the logic in it.

In the letter I wrote to the department I said I would be traveling during my delayed year in order to photograph national monuments that were sinking into the earth along with the reputations of our best educational institutions. Later, I regretted dropping this into the mail slot and then I had to call and ask them not to open the letter, a second would follow, and so on.

From the glossy postcards that continued to arrive every two or three weeks from Dad to Lola, I began to believe that if everything else was going to hell, our father had plenty of beaches where he roamed and that the skies were always blue.

You should see the ocean, he wrote on one card.

You should see how broke we are, I almost wrote back. How Mom doesn’t sleep anymore, how she worries about things you can’t imagine.

Mom held up a copy of The Secrets of Car Flipping. I didn’t realize at first that she was saying she had to sell the station wagon.

“When I went to that retraining session at the newspaper,” she said, “I met a new hire named David, and during the break we talked cars. He just called to say he has to sell his father’s van to help pay for his dad’s home health care. David had his mechanic check it out, and he says it will run until Armageddon.”

That’s one of those statements you have to think about, but I’m not sure my mother did, given her worries. David drove over to our place the next day so she could give the van a spin. He had hair popping out of the edges of his long-sleeved shirt, cuffs and collar, like a physical manifestation of the energy exploding from his psyche. His father, he said, had babied the thing.

“He’ll only sell it to someone who loves it as much as his father did,” Mom told me after he was gone.

“And?” I asked.

“Well. I could haul an awful lot around in something like that. He said he’d give me an exceptional deal and he offered to pitch in over the next year, change the oil, replace the belts, that kind of thing.”

“Was he hitting on you?” I asked.

She reddened, and I felt certain some flattery had been involved. “He showed me a picture of his wife and kids. He has a son your age and …” She stopped and said, “He’s going to list it next Saturday.”

Over the week, she hesitated and worried that the van would be sold out from under her while she hesitated. She read something in Consumer Reports and talked to her bank and her brother, Hal, who wasn’t all that encouraging but didn’t have any other ideas. He wasn’t a car man by nature.

“What do you think?” she said, circling back to me.

It’s not like I knew what she should do. We were both in shock about having to sell our wagon because it had felt so safe driving Lola around in a Volvo. But it was time to get over it and stop asking people. I told her this and she went for that van as if she were leaping from a high-rise, convinced someone would bring out a net if the sidewalk got close.

Fourteen days after we got it, the van sprang an oil leak, and that hairy guy no longer answered his phone. Was it possible he wasn’t actually employed by the paper? Was he just there at the training session to sell someone a bad vehicle? Was this a business venture or a lark? Did he sell other goods as well? Broken radios, busted dishwashers, books with their front covers ripped off?

Mom was too exhausted to puzzle this out or to track him down, and it probably wouldn’t have done much good if she had. She began to use cans of this additive to patch the leak. By then we had two leaks, maybe three. When she fired the engine up it smelled like something was burning or dead. The undercarriage dripped and black oil pooled everywhere we parked. Before, when she picked up Lola from a play date, Mom used to pull into her friends’ driveways, but now she made a point of parking on the street—sometimes on the other side of the street or down the block.

Another letter arrived.

Dear Mona,

So I said I’d tell you a story about my Uncle Sorohan, my mother’s brother. I knew him during his carny years, but before that he was a roustabout with a circus, when he was even younger than you are now. Uncle Sor had an old fedora he never took off, even in the tub and even when he went to bed. His face was deeply lined from all the cigarettes he smoked and years of being outdoors, and he was a hardworking man but also a true romantic.

He often stayed for a night or two if he was on his way through town, and one time, I must have been five or six, he drove a flatbed to our house with a tall wooden cabinet painted red and roped in the back so it stood straight up and down. The cabinet had a few crude paintings with oriental dragons on one side and a woman in a kimono with a strange stare painted on the other. In the front was a door. I guess it was inevitable that a boy of five or six would get curious, and so after dinner Sor found me in the flatbed, trying to peek inside the box.

You know my father drank rashly, and he had worked himself up and warned my uncle at dinner that he better get that thing out of the drive early so he could move his patrol car sitting in the garage.

When Sor found me up in the flatbed, he climbed up and opened the door to the cabinet and asked if I’d like to disappear. There was a makeshift seat inside, like a phone booth without a phone.

“Where would I go?” I said.

“That’s the question. Where do we go when we disappear? I believe I disappeared into the circus, but you might disappear into the police force where your father hides out if you aren’t careful.”

“No, where do I go if I disappear in the box, Uncle Sor?”

“Oh, the box. You go somewhere else. I’m not really sure. I hear it’s quite pleasant, but I wouldn’t recommend it for everyone. The last man who tried it stayed away for years until a magician came along with the right spell. When he tumbled back into the box finally, and his wife asked where he had been, he seemed too happy to speak. Here, help me with these ropes.”

Soon we had the magic disappearing box out of its anchors and I was helping him bring it into the house. It was surprisingly light. As soon as my father saw it, he blew up at my uncle for being a bad influence and stirring up one kind of trouble or another. My mother did what she could to calm him. But Uncle Sor just ignored my father the way he always did. He directed me to turn to the left and then the right and watch the top stair so we would clear the bannister. We put the box at the foot of my bed.

“I’m going to leave this with you for a while,” he said. “Now, you need the spell so you’ll be able to come back if you try it out and there are no magicians around.” And so he gave me this: “Upon the brimming water among the stones are nine-and-fifty swans.”

I heard the basement door slam, and I knew my father had gone down to the family room, where he had built a saloon and where he would drink, mumbling to himself, and fall asleep with his head on the bar, hating the world. My uncle went down to the living room to sit with my mother and talk in whispers—I imagine trying to convince her again that she should leave my father.

The next day my uncle was gone before dawn and my father went off to work and my mother made me lunch and I was off to school. It was the following weekend my father went out with his buddies and came home stinking drunk and went after my mother and me as if he were invading an enemy camp.

After my mother had given me a cold compress for my face and after she had taken her quiet medicine, she stretched out on her bed with her own ice pack. I went back to my room and got inside the box, and that’s when I discovered the trapdoor. If I lifted up the floor using this tiny bit of rope in one corner, I could crawl into a box in the bottom that had air holes drilled into the back.

It took me a few years to understand that the spell was one of Yeats’s and that my uncle had built the box with his own hands to a purpose. I discovered I could curl up and hide out when my father was hunting me. He would open the door in the midst of bellowing and tearing things up around my room, but that was about it. He probably thought a disappearing box was too easy and simple-minded a place to hide. After all, he was used to working with professional criminals. I only wish that I had had a disappearing box for my mother.

The summer I joined my uncle on the carnival circuit, my father took an ax to that thing and started a bonfire with it. I imagine he had found out about the hiding place.

It’s always been my Uncle Sor I’ve wanted to emulate, never my father.

Before I close, your mother tells me you’ve decided to take a gap year. I hope you know I’ll be excited to hear your plans. You have a good head on your shoulders, Mona. It’s not a bad idea to build up some savings, but if you look at internships, we’ll have a room for you once we find the right place here. Public transportation is pretty good and we’ll make it work.

Love,

Dad

Sometimes I think my father’s drive to New Jersey, away from us—perhaps especially from me—began when I turned nine and started to assert my independence, speaking up in ways I hadn’t before. When we bought the house he worked longer hours and I had things to do with my friends on the weekends. I got used to Mom filling the spaces and became less interested in what he had to say. He became fragile if I was busy and didn’t have time to do something he hoped we might do—bowling, batting practice, miniature golf. As I pushed further into my own life, he appeared sullen or withdrawn. My mother understood life and art and what we’re here to do. He understood insurance.

I think he tried again to be this imaginary father when Lola was born. But once you carry a lack of confidence, it’s hard to hold a baby in your arms without thinking you’ll drop her.

After that we barely spoke at all.