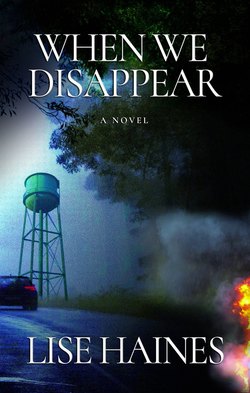

Читать книгу When We Disappear - Lise Haines - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Mona

ОглавлениеMom removed one of the grilled cheese sandwiches she’d built into a mound. She cut it into fours for Lola who was watching a show in the other room.

I asked my mother if she and Dad were still together. “I’d rather know,” I said.

“Did he say differently?”

She knew he was sending letters to me and she had tried not to probe. In the past, she simply reassured me. I watched her pull another sandwich from the pile and quarter it without really looking.

“He makes it sound like you and Lola are moving to New Jersey imminently. But imminently has been going on for months. And if he isn’t sending enough money, what are you moving on?”

She looked out toward the yard where one of her sculptures sat. She had been with my father since they were teenagers.

“He doesn’t fly in to see you. He doesn’t send you tickets to see him. Don’t cut my sandwich,” I said.

She looked at the pile and stopped. There was only one whole sandwich left. She took a measured breath. “We’re trying to save for the move.”

“There’s something you aren’t saying.” I picked up my photo bag, about to leave.

“Wait, you haven’t heard my news. You remember my friend Tom Watts—the one who does the ceramic pieces with those incredibly thin walls? It looks like he’s convinced an editor at Architectural Digest to attend my opening. With a photographer. I think our luck is turning.”

I just shook my head.

“I know. You don’t like the idea of luck,” she said.

“Not really.”

“I’ll do the eighth pour,” she said, setting her jaw. “I won’t leave anything to chance.”

“I wasn’t saying … I just meant you’ve worked really hard. It has nothing to do with luck. This is such good news.”

“I’ll feel more confident if I do the eighth.”

This meant she would have a new bill to pay at the metal forgers. Her sculptures required jumbo flatbeds, blankets and drop cloths, spools of industrial rope, crates and commercial cranes to move them. When I brought this up, she said, “Things have a way of working out.”

The night of the opening, she appeared to be right. Golden lanterns hung in the rafters of the gallery. They reflected my mother’s work in a striking way, magnifying everything she imagined to be true that night. She sold two of the smaller works within the first hour and had promises for more sales, the gallery owner taking a deposit on one of the largest pieces for a corporate client. A favorite of mine appeared in the magazine. We weren’t on solid ground yet but we could see solid ground floating out in front of us.

But this was 2007, and shortly after the magazine article appeared, the gallery called to say the corporate client felt it was prudent, based on current market indicators, to hold off acquiring any new art at this time. The subprime market was buckling. The economic crisis had begun. She received a kill fee. And like that, the gallery owner began to express doubt about selling her work. “Maybe when the economy picks up,” she said.

Mom had several pieces of mid-century modern furniture that she began to sell off. One Italian chaise, an Aalto, drew down two thousand dollars. After the new owners left with it she went up to her bedroom to lie down. The chaise had been her grandmother’s.

In time we were turning and looking before taking a seat to make sure a couch or chair was still in place. She embellished the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears to keep Lola from worry, saying, “The chairs are out for repairs.”

I was out roaming one evening with a 28mm lens on my old digital SLR. When I came in and started up the stairs to the second floor, I heard Mom on her speakerphone. I assumed she was talking with Dad. The light from her bedroom pooled on the carpet in the hall and I sat down near that pool and listened. Lola was already asleep.

It was her brother, Hal, the high-end banker who sat on several boards, drove a Mercedes or two and fed regularly on pate. She often expressed her confusion that they had been raised by the same parents in the same house.

I was about to get up and head to my room when I heard him say, “I’ve gone over that.”

“You can’t be serious,” she said.

“Have I ever not been serious?” he asked.

Maybe he meant to say, when giving advice. But Uncle was a cheerless soul, and his second wife, Margaret, was worse. My mother choked up rather than answer.

“This is about the housing bubble,” he went on. “You need to sell the house and find some practical work while you can. If things go as badly as some of us think we could all be underwater. My money’s tied up or I’d buy one of your objects to help out. You know, if Margaret had any eye for art.”

Normally my mother would have said, One of my objects? in a pointed way. It troubled me that she had gone mute.

“You’re absolutely certain?” she said finally.

“Have I ever not been … ?” That unsaid word filled the house like a gas leak. It was a good thing we had learned to avoid matches.

Mom met with a Realtor a few days later, set some potted plants in bloom around the front steps, and trimmed the hedges. Our property was a little odd, and Mom wasn’t sure how the sale would go. The small house had once been the butler’s quarters on a large estate, but it and the tall barn-like garage that could store up to six cars had been split off and sold as a parcel years ago. She decided to keep the price low. The crash wasn’t in full play yet, but she wasn’t taking any chances. After paying off two mortgages, we leased an apartment in Rogers Park in a far northeast pocket of Chicago. Without a proper space to work in, it was clear that she would have to quit sculpting cold turkey or find someone to lend her studio space. She made a stream of calls. It was unfortunate that she worked so large. Mom said something romantic to me about the benefits of a fallow period though I saw her smart.

We left our keys in the kitchen where Dad had tossed his.

The new place was a one-bedroom apartment at the top of a three-story walkup. There were six apartments in all. The L ran along the back side of the building causing a noticeable trembling and a high, piercing sound every few minutes, and the parks appeared to be full of junkies. She had looked everywhere. It was either this or head into a spiral of credit card debt.

“You’re taking the bedroom,” Mom said as we looked around.

Standing by the bedroom window, I could see the faces of passengers looking our way as if they hoped to catch someone fighting or hooking up or breaking down or shooting up. But I didn’t complain about the location of my room. I would be the only one with a bedroom door. “Lola gets the living room,” she said. “And I’ll take the dining room. I can use the highboy and the two Japanese folding screens to make a little privacy.”

I was having a hard time hiding my anger at all this sacrifice. “I’ll take the dining room,” I countered. I turned to face her but she shook off my signal.

By late afternoon we had looked through all the boxes marked Lola and hadn’t found her dolls. Starting down the stairs to check the car, I stopped when I saw a guy backing out of one of the two first-floor apartments. He was pulling a T-shirt over his head, clearly in a hurry to be somewhere. When he turned and saw me, the voice of an old man came from inside the apartment.

“Ajay! Ajay! Do not forget to lock the door!”

It wasn’t the work Ajay had done on his body that pinned me to the stairs. I didn’t care about things like that. But it was like bumping into someone with the same features as a lover or old friend—he had a familiarity I didn’t know what to do with. He smiled and I found it hard not to smile back and that made me feel even more peculiar.

Returning upstairs, I told Mom I had forgotten the keys and would go down again shortly. I mentioned seeing one of our neighbors—this guy on the first floor who seemed nice—and then I got back to work.

I was surprised when she brought him up late in the afternoon. The weather was burn-in-hell August. We had no AC, and we hadn’t found the box with the tower fan. She kept saying, “Maybe the movers stole it.” And probably by the time we were completely unpacked there was no other way to account for the missing items. She had found the movers on the cheap. But I doubted a tower fan would have done much good. The heat from all three floors rose steadily and came to a dead stop in our unit.

As I unpacked Lola’s picture books, I lingered over one I had read to her a hundred times, Bye Bye, Baby: A Sad Story with a Happy Ending. Lola was on her raw mattress on the floor, dropped into a steady nap. We were still looking for her circus bedding. She told us she wouldn’t sleep on anything else. I had no idea how we were going to get the bed frame assembled. It was one of those Swedish products with a million pins and bolts and one small Allen wrench.

Mom stood in the opening to the dining room. I looked up at her face, streaked with sweat. No one had alerted us that the super would leave old food crusted in the refrigerator and cabinets, rat droppings under the sink, a broken toilet roll and towel bar in the bathroom. All of this, Mom said, was to be taken care of along with the promise of fresh paint in all the rooms, and we got none.

She too had run into the first-floor neighbor on one of her trips up and down.

“He has the look of a drug dealer. Ignore him if he tries to talk with you. Avoid any eye contact.”

“That sounds kind of … racist,” I said.

“Don’t go there,” she said. She knew I was trying to drop this guy as a subject, but her face lit up. “We’re in a high-crime area, that’s all I’m saying.”

“But this is where we live now,” I said.

“But he’s lived here longer,” she said.

I could almost see her brain fuel up, logic peeling off like broken heat shields. Putting the last stack of books on the shelf, I looked at her as she began to arrange T-shirts and pants in Lola’s drawers. Each time she folded an arm or leg, it was as if she were trying to get an unconscious child to move her extremities. I knew how she worried for Lola.

Just then I saw Ajay outside. He grabbed a large bottle of detergent from a pickup truck and walked around the side of the building.

“Eighteen shootings last year,” she said. “I won’t tell you the number of stabbings.”

“We have an understanding,” I said.

The understanding went like this: I would do my share of housework, help with Lola, and pay for some of the utility bills—at least my phone and data use—while I saved up to move out. She would pay the rent, buy the groceries, and so on. Meanwhile, I would keep my own hours, set my own rules.

“Well yes, but …”

An elevated train went by, and I shouted, “I’m going over to Howard Street for ice!” I knew I’d get no argument. The refrigerator had been unplugged when we arrived, and it still wasn’t cold enough to make ice cubes. Grabbing my wallet, I fled.

I stopped outside the basement entry on my way. The air that came up through the doorway was remarkably cool. Going down the concrete steps, I walked through clumps of lint and dust.

Ajay stood in front of a bank of coin-operated washing machines, about to pour his detergent into the cap. When he looked up I saw the blue liquid ribbon over his hand before he realized what he was doing. He shook his head, smiling to himself. Rubbing his hand on the clothes, he said, “I’ll be out of here in a half hour. The third machine is a clothes shredder by the way—skip that one. I’m Ajay.”

I stood there for a while trying to figure out why it was so pleasurable to throw him off guard. I came closer and saw that the clothes in that one washer were so thickly coated in blue detergent now there would be an overflow of suds down the washer and across the floor as soon as he got it started.

“How many quarters does it take?” I looked at his eyes instead of down at the slots. There was that peculiar sense of intimacy.

He reddened a little and broke away to wash his hands in the sink. “Eight for the washers, at least four for the dryers.”

Then I heard him say, “And you are?”

But I was already halfway out the door and didn’t turn around.

You do something weird one day and there’s no way to follow that except to get weirder still or stay out of sight. So I avoided him. And that had nothing to do with my mother.

He called out to me a couple of times in the weeks that followed and I almost stopped to talk. I thought of telling Nitro about him, but it took a lot to stir Nitro.

I met Cynthia Carshik when I returned from the store that first day. She was sitting outside her apartment on the stairs, moving the air around with a paper fan. The large window on the landing was open. The humidity was awful but there was a breeze.

“See that,” she said, pointing outside. I looked out at the massive dark cloud over Lake Michigan.

“It followed me home,” I said.

“Then you’ve brought rain with you. Thank God.” She introduced herself and said, “Hell of a day to move.”

“Any chance you have a can opener we could borrow? We haven’t found ours yet.”

She loaned me hers along with a cooler. Then she offered me a cold beer and told me about the people in the building. I took a seat at her kitchen table.

“Ajay lives with his grandfather on the first floor. He graduates from architecture school this spring. Women love him by the way. He had a girlfriend for a while, but he dropped her. He seems pretty serious about what he’s doing. Oh, and the iron gates and the sheet metal and pipes in the basement are the grandfather’s. You’ll notice them when you’re trying to get to the washers and dryers sometimes. He doesn’t like to have anything disturbed. If you ask him to move a fire grate, he’ll stare you down. But the next time you go down to the basement every last thing will be swept and stacked. He has a small welding business with a partner, so he tidies up when the work goes slack, not before. Though he seems to be working less now.

“Across from the Kapurs is a man named Neil and his wife, Rabbit. They’re tattoo artists. The guys in the apartment next to me are probably going to be evicted next month, don’t ask. And the old woman who lives next to you, all her mailbox says is Lily. You’ll never get her to talk. You can look her in the eyes and shout, ‘Good morning!’ and she’ll look right through you. And no, she isn’t deaf. I’m pretty sure she lives off Social Security or disability. You’ll see her wander around the neighborhood with an old camera. I’m sure she doesn’t have any film in it.”

“No film?”

“She just seems like that type.”

Cynthia was twenty-two and worked at the comic book store on Howard. She and I were the same height, close to the same build, listened to a lot of the same music and were nervous driving cars. I swallowed my fears to get Lola around, and Cynthia mostly clung to public transportation but kept her mother’s old car running. We had both had scarlet fever and liked to watch silent films. Cynthia smoked herbal cigarettes and had done insane things.

Her bedroom was directly below mine, and she had converted the walk-in closet between the dining room and bathroom to a tiny bedroom for those occasions when her musician boyfriend Luke’s three-year-old son Colin visited. There were Cubs pennants on the walls, lion bedding on the cot, a small nightstand with a lava lamp. All the hangers had been removed from the bar, and there were board games and plastic tubs full of toys up on the shelf. She had hoped he would stay over more often, that he or Luke would settle in, but Luke had taken off for New York with his collection of guitars and amplifiers just before we arrived. She said she had a recurring nightmare that went like this: “Luke returns for a visit from New York and we get into bed that night. The Ravenswood train makes its approach along the building and suddenly the cars jump track and drive into our bed, taking him out but sparing me. The last person who had your apartment said sometimes my screams were so loud the sound shot through the radiators,” she said, apologizing in advance.

I said that if I heard her scream, I would take something, a book or cup, and tap on the pipes so she’d know someone was there. She said she would do the same for me, anytime.

Before I dropped off that night, I thought about what holds us together. When I was little I could almost see the cord that stretched between my parents. He would stand behind her while she sat at the dining table, and he’d put one hand on each of her shoulders and rub her muscles and she would look content. He was doing well, selling plenty of policies. She was sculpting. Mom and he would make a point of dressing up and going out one night a week. She often wore full skirts cinched in at her tiny waist, and just before they left the house he would ask her to turn in a circle to show off her outfit, commenting on her legs as the skirt lifted in the air. He wore nicely fitted suits and ties, and his shirts always looked new. They were a handsome couple.

Maybe the cord frayed when she began to outpace him. She continued to work part-time to help with the mortgage since her costs as a sculptor were so high but often found ways to do this at home. She had become, however, a sculptor with gallery representation. And he got a new boss and began to feel pushed around at work. She did her best to hold him and the life we had together, but then his job disappeared. My mother told me losing his job was like a picture he kept folded in his wallet that he transferred from one outfit to another. Every time he paid for something, every time he’d think about what he was doing, where he was going, he’d see that picture.

It didn’t help that she liked classical music and stayed up half the night looking at images of art while my father spent increasing amounts of time watching crime series and the kind of talk shows that turn into brawls. As things ground gears, the volume cranked. I heard Mahler’s Eighth Symphony at earsplitting decibels while some sister’s boyfriend’s lover’s husband went down with a sonic boom before a live audience.

If relationships split along certain lines and we tend to fall out on one side or another, I knew my side. Sometimes in those days I got in bed with her and we watched a stream of visuals on her computer well past midnight, or drifted into movies, while he pitched about on the couch with his shows. We preferred stuff flooded with one brand of love or another, even airless romances that bring the wind back up into your throat, and the French films my mother adored where little happens.

It’s possible I was waiting for them to fail. By the time I was in seventh grade, somewhere between a third and half of my friends’ parents were divorced. Some should have been but weren’t. And statistically, I read in one of my mother’s magazines, half of the group that was left cheated, and half of that half felt they were doing more than their share of the housework and child-rearing or missing out on their real ambitions. Halve the last bit again and there was a small collection of funny people left to dodge inevitable heartache.

There were two couples. A friend named Deena who had two moms, both doctors, and though I didn’t spend a lot of time at Deena’s the moms seemed to be in decent sync whenever I dropped over. And Joe’s parents, the first to get a jumbo flat screen TV. We used to pile into their house on weekend nights. When we weren’t watching a movie or playing a game, pictures of the family would come up on the screen, the father’s arms around the mother, the mother’s arms around the father. They weren’t little people by any means. They liked to eat and have all of us for barbeque, baked potatoes with sour cream, garlic bread heavy with butter, and so many beverages stuffed in the icy cooler you could float away. They rarely raised their voices except to call out for more sauce or napkins. Even their kids said they just worked somehow.

When I realized I could only find two larger-than-life couples in the whole lot, I guess I lost faith in the idea.

At school the boys I knew were friends mostly and we traveled in packs with the girls I knew, and I watched them hook up and fall in love or the other way around. They broke each other’s hearts in the middle of movies, over cheap meals, on the phone, in fragmented texts, by ghosting.

My friends said I was too shy, that was my problem, but there was a boy who ran after me into Lake Michigan once and tried to tug my bathing suit off. Another one kissed me in a locker room as if I were a sport he had to win. I had crushes and months of sadness over a third guy but mostly I watched everyone else travel around fortune’s wheel, getting snagged and ripped on its nails.

When Nitro came along, things made their own kind of sense. I didn’t want to be a couple, at least on the conscious side, and neither did he.

That made it extra strange to wake up one morning curled in front of Ajay’s door in my pajamas. Mr. Kapur, his grandfather, stood above me. The morning light was coming up from the entryway. I had no idea how long I had been lying there.

I had mostly seen Mr. Kapur in passing, and he had one of those faces. Wiry and strong, he could have been fifty, but he could just as easily have been seventy or even eighty. He wore the same kind of jeans I had seen him wear each day on his way to and from work. His shirts were neatly tucked in and buttoned to his knobby throat. He was a welder by trade, and I sometimes imagined he and my mother might sit around talking shop.

His cowboy boots, in a state of high polish, were inches from my face. A sailing verbal assault began. “Get up, get up, get up! Do you have no shame?”

I worked my way to a seated position.

A crush of Hindi words followed as I brushed a layer of grit from my face. I asked him the time.

“What time is it? What time?” he mocked. “Six a.m. precisely. You would like the weather report now?”

“How long have I been here?”

“I am getting ready for work, going down to get my newspaper, and the girl from upstairs asks me this as if I have been standing outside my apartment all night long to see if some lovesick person will wander by and ask for a detailed report on conditions?”

“Lovesick?” I said with a laugh. I got up and took a seat on the stairs, too wiped out to make the climb to the third floor yet.

“My grandson is not a movie personality, and I am not the morning news station.”

“Your grandson is not … ? I don’t have any interest in your grandson.” It’s possible I reddened a little but if I did he didn’t seem to notice.

“What is wrong with you then? Making a spectacle of yourself.”

“Sleepwalking,” I said. “Sleepwalking is what’s wrong with me.”

He softened a little and said, “Then you have a nervous condition. You should see a doctor.” Leaving me for a moment, he went into the apartment and came out with a blanket that he draped around my shoulders.

I was going to say something about the uselessness of doctors but decided to drop the subject. Just then the low sun rolled further into the lobby and hit the hall window on the landing between the entry and the first floor, the reflection beaming directly into his face. I thought that’s why his eyes began to fill.

“Are you all right, Mr. Kapur?” I asked.

He looked disoriented.

“Mr. Kapur?”

Stepping out of the beam of light, he seemed to consider me anew. “Are you not the girl from upstairs? If you are going for your newspaper, you should wear a robe,” he said. “Did no one raise you correctly?”

“I …”

“It is a matter of common decency,” he said. Then he got his keys out and quickly disappeared into his apartment. I wondered if this was a one time incident or if his condition was progressive.

We rarely saw Lily, the woman who lived next door to us. She would leave her apartment once Lola and I were out of the house and Mom had gone on the clock with her phone sales. She returned before Lola’s afternoon pickup and long before I got home. It was almost as if she wanted to avoid us. Mom saw her figure from our living room window. She wore an old hat and coat and beat-in flats. She always had a camera with her and this made me think of the ghost images she must have inside. So far none of us had come face to face with her.

Though Mom often lost herself in her work, she was by nature gracious and warm. She liked to extend herself and offer help where she could with old people in particular and had volunteered at the senior center in Evanston for many years. Placing a plate of fresh baked cookies by Lily’s door one day with a short welcoming note, Mom hoped to strike up a conversation. The plate sat there untouched until Mom removed it, worried about drawing vermin.

One morning Mom got curious and, purposefully breaking her routine, stepped into the hall when she heard Lily’s door open. Lily was a tall woman, and she looked weary, my mother said, her face deeply lined. She had a Rolleiflex on a strap around her neck. Lily looked her square in the face, coughed as if Mom was a small bone to get out of her throat, and hurried back into her apartment.

It was sometime later that Mom agreed to accompany Lola’s class on a field trip, and I came home early with a migraine. My head was splintering as I got to the top floor. I noticed Lily’s door was ajar. I waited for a moment, trying to figure out if I should do something, but finally decided she’d be annoyed if I knocked.

All I wanted was to lie down with a compress and sip a cold Coke. If I got a dose of medicine quickly, I might avoid a forty-eight-hour siege that would include a light show and severe vomiting. The bottle of medicine was empty. I called the doctor’s office where we had gone for years, and they agreed to send a prescription to the pharmacy near our apartment. I rang Cynthia to see if she was willing to pick it up, but she was out. If I rested, even for a moment, I would be down for the day. Somehow I walked over to the pharmacy on Howard and got my pills and walked home.

When I returned Lily’s door was still open. I thought about my own grandmother, my mother’s mother, and what it would be like if some neighbor ignored a warning sign of a stroke or a fall. Knocking a couple of times, I got no answer. I stepped inside and found a small table and a chair set by the window, looking out toward the lake, the wood floors bare, no other furnishings.

Maybe it was the sparseness, but everything felt still. I called out before I entered her bedroom. A single bed and a small dresser stood watch. Her kitchen seemed to hold only the most essential items. No framed artwork or family pictures. Nothing on the walls. She had the same built-in shelves in her dining room, but where our cabinet doors had panes of clear glass she had backed hers with dark fabric.

The starburst effect from the migraine began, and in that awful glow I thought I must be hallucinating when I found rows of camera bodies and lenses inside the cabinet. A couple of old Kodak Brownies and a Rolleiflex 3.5T, along with a 3.5F, 2.8C, and an Automat. She had a Leica IIIc, an Ihagee Exakta, a Zeiss Contarex and a slew of other SLR cameras. It was impossible that all this beautiful machinery—a collection of cameras that might have taken a lifetime to build—was housed next door. I examined a few and though none had film, the mechanisms worked perfectly. I wondered if she counted out her wealth with regularity, sitting at her little table.

The halos of light grew worse, and I hurried now. The bathroom was, for all intents and purposes, a darkroom with an enlarger, trays and chemicals, though I did find a hairbrush and a bottle of shampoo. Lastly, I pulled back the set of curtains to the walk-in closet slowly so the sound of the metal rings moving along the pole wouldn’t peel through my skull. Inside, hundreds of neatly stacked print and negative boxes lined both sides with an open stepstool in the middle. Against the back wall the boxes were almost to the ceiling, each one clearly marked with dates and subject matter or location. I pulled one print box off the top marked Downtown, 1965.

The work was tender then gritty, cold-eyed then heartbreaking and almost uniformly luminous. Blacks were true, deep black, whites crisp. I pulled open another box and another. I lost track of time and place and even my head seemed to throb differently in those moments of discovery. Weegee, Dater, Cunningham, Bresson somehow all resided in her images yet she was her own photographer. Lily was her last name. Her first name was Anna.

I thought of Nitro, how much he would love this work.

Over decades she had taken photographs of people in every social class along with self-portraits, often in mirrors and windows, some of them of her younger self fully nude. As far as I knew, Anna Lily was unknown.

I heard my mother and Lola on the stairs, talking as they climbed. Then our front door opened and closed, and the TV went on with a kids’ show. I put everything back and at the last moment grabbed one box of negatives marked Arlington Racetrack, 2002. I could never steal anyone’s cameras. But if I borrowed a few of her negatives and prints for my own small use and returned them.... I felt far more nervous with her negatives than I did when I’d stolen a two-thousand-dollar pair of shoes. Before I left I made sure everything appeared to be undisturbed.

I gave myself a minute, tiptoed down and walked up the last set of steps, and arrived at my door, where the pain in my head finally blossomed. Once I was inside, Lola rushed to tell me about her day at the Aquarium while my mother said, “You’re home early.”

“I have to lie down,” I said and held up the prescription bag. Mom swung into action and got me a compress and a Coke over ice and asked Lola to start her homework at the kitchen table—she would fix a snack in a minute.

I got on my computer the next morning and discovered in the world of photographs published, shared, pilfered, over saturated, distorted, lost, retrieved, and made to express every sentiment on earth, there was nothing by a photographer named Anna Lily. Not a single image.

I was mulling this over when I realized my mother had placed a new letter from my father on my desk.

Dear Mona,

When I first got to New Jersey, I found a shortcut to work. This took me by a tract of upscale homes without personality and a stretch of manicured park that no one seemed to use. Eventually I got to a long row of estates that made me think I was driving through a Hollywood set. My boss has his home there and his pool, his tennis court and his little stable—most of which he doesn’t use because he goes to clubs for these things. Each day I was left with a feeling that my temporary world, in this 1950s motel room with its hot plate and view of car dealerships, was rather small.

It was the motel owner who suggested another route and something I might do if I was willing to leave earlier. The next week, instead of turning right at the main bridge I went left and this took me by small brick homes built in the 1940s, most of them well kept, the lawns trim. And then the sad places began, the abandoned houses and the ones where people can’t keep their porches repaired, the windows from getting broken, and the nails in place. This is where a line of men wait, hoping to get day labor. And this is where I was instructed to stop.

I went over to a food truck. Later in the day this truck will sell burritos and pulled-pork sandwiches and icy drinks to men and women who work downtown and line up halfway down the block for tasty home cooking. But in the mornings the day laborers, who are mostly homeless and might not eat otherwise, are given a hearty meal. I was welcomed by the owner, who provided all of this food on his own dime with only a small fund his church had set up. And so for forty-five minutes I helped wrap the food and hand each man a meal so generous he could eat some for breakfast and save some for lunch and get through.

Honestly, I think it’s getting me through the days.

I miss all of you deeply. I am sorry that coming home has been delayed so long. Your mother’s probably told you by now that I am still waiting on my commissions. Maybe the boss had to build a new swimming pool this year. I’m sure things will be straightened out soon. Please try not to worry.

Love,

Dad

I began to look for something I might send in return. Some message to let him know how I felt about his rules to live by. He probably had a new home in New Jersey with some girlfriend and her kids. Because once you’ve lied, especially by omission, you can always lie again. It’s like stealing. The difference was, I knew when I stole.

Then I found it. Mom got the paper delivered for free because of her ad sales. They stacked up by the kitchen door until we took a bunch down to the trash. Right there on the top, on the front page, was a full-color photograph of a car accident that had happened on Lake Shore Drive—two cars smashed together as if they had been propelled by anger. Emergency vehicles with their lights, stretchers, bodies in braces, blood on the asphalt. I got one of my digital cameras and shot this image. I downloaded it, cropped it to remove the caption and ran it out on my printer on the kind of paper stock that makes a good postcard. On the back, all I put was my name and address in the upper left-hand corner and his name and address in the To: space. I stamped it and went downstairs and dropped it in the mail.

He had a talent for metaphors. He could tell his own story.

After that his letters stopped.