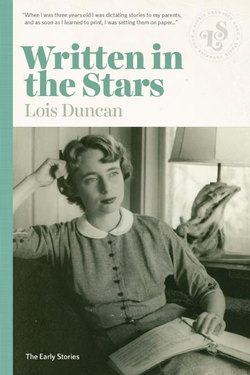

Читать книгу Written in the Stars - Lois Duncan - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеReturn

The curtains were crisp and ruffled at the windows. Outside it was still not quite dark, still just on the edge of twilight when fireflies were beginning to twinkle in the hedge by the walk.

Inside, the kitchen was warm and bright, and the biscuits were baked a little too long, and the woman was smiling across the table while the little boy was feeding a chicken wing to the cat.

Bill looked at them and thought, Well, I’m here.

He thought it in an odd, detached way, as though he were not really there at all.

Last night on the train he had buried his face in the hard Pullman pillow and thought, Just seventeen more hours! Just seventeen more hours and I’ll be home! He had seen himself crossing the yard, opening the front door, going into the hall; he had smelled the cedar wood chest and heard the tick of the hall clock. Then he had gone through the living room into the kitchen, and they had all been there—the woman and the little boy and a serious man with graying hair—and they had hugged each other and laughed and eaten supper together in the kitchen with the twilight outside.

Last night he had been terribly excited.

Now he was here, and he was not excited at all.

“What’s the matter, dear?” asked his mother anxiously. “Are the biscuits too brown for you?”

“No,” Bill said quickly. “Of course not. They’re just the way I like them.”

“You’re not eating very much, dear.”

“Yes, I am,” Bill said. “You just haven’t been noticing.”

He helped himself to another biscuit and buttered it industriously.

“Do they feed you biscuits in the army, Billy?” the little boy asked with interest.

“Sure, Jerry, but not like these.”

“I remembered how you always liked biscuits,” said his mother, “so the first thing I thought when we got your telegram was how we could have biscuits for supper when you got home. Remember how you and your father used to eat two whole plates of biscuits at one meal?”

“Yes,” said Bill, and then he said, “It seems odd without Dad.”

“Yes,” said his mother. “It does.”

The light went out of her eyes, but she still smiled, a determined smile.

“I—I didn’t get your letter about the accident until six weeks after it happened,” Bill went on awkwardly. “We were behind enemy lines and weren’t getting any mail. I wrote as soon as I heard.”

“Yes, dear. I’m sure you did.”

“I guess maybe I didn’t sound like I wanted to. I don’t write very good letters.”

“It was all right, Bill,” his mother said. “I understood.”

Bill nodded gratefully, but he knew she had not understood, because he had not fully understood himself. There had been a stack of letters at one time, ten from his mother and sixteen from Mary. He had read Mary’s first—Dearest Bill—chitchat about college, the last football game, Arden and Mike going steady—I miss you so much. All my love, Mary. He had read slowly and pictured her as she wrote, her face flushed and pretty, her pen racing along the page as she spilled out her thoughts helter-skelter before they had time to get away. When he had finished, he started his mother’s letters—accounts of the Garden Club, Jerry’s toothache, a new paint job on the car—and finally, the accident.

The letter about the accident had been heart-breaking and brief.

Bill had read it carefully and laid it aside. He had thought, My father is dead, but he had not felt any great sorrow, only numbed disbelief.

That night he had dreamed about rows and rows of men, all dead, but none of them was like his father. They were young men with drawn yellow faces; and suddenly they weren’t dead at all, but twisting and turning and screaming in horrible fits of agony. The dream was so real that he awoke with a scream ringing in his ears.

He had lain very still in his blankets and thought, My father is dead. But he could not believe it was true. Death was something close and horrible and frantic, something his gentle, easygoing father could know nothing about.

He had groped for his flashlight and, when he had found it, he had read Mary’s letters again. I miss you so much. All my love, Mary.

When he had gone to sleep that time, he had not dreamed again.

Bill jumped as the cat wound itself around his leg.

“New cat, isn’t it?” he asked.

His mother said, “A female cat came along, and Tuffy went away with her. This is Pepper.”

Jerry leaned forward in his seat, a small, pale boy with glasses.

“Billy,” he said eagerly, “did you ever kill anybody?”

After a moment Bill said, “Yes.”

“With a gun?”

“No,” said Bill. “With a bayonet.”

His stomach contracted and the chicken tasted like meal.

His mother said, “Jerry, you may excuse yourself and go upstairs to your room. I’ll be up to talk to you in a few minutes.”

Bill felt the bayonet, warm and strong in his hands. He felt it pressed against him as he ran. He saw a man in front of him, and he watched the end of the bayonet, and he saw the man’s face when they met—

“Oh, Mother,” Jerry protested, “why? Why do I have to go up now? It’s not even half-past eight yet!”

Bill got up quickly.

“I have to go,” he said. “I’ve got a date.”

“But, Bill, you haven’t had your dessert yet!”

Bill said, “Save it for me and I’ll eat it later. When I talked to Mary on the phone I told her I’d be by at eight-thirty.”

He went outside. It was really dark now, and the fireflies were fairy lanterns across the lawn.

Bill stood in the darkness and breathed deeply and the sickness went away. Then he got into the car and drove to Mary’s.

Her father came to the door. He was much smaller than Bill remembered him.

“Well,” he exclaimed, “look who’s here! How are you, Bill?”

Bill said, “It’s good to see you.”

They shook hands. Mary’s mother came in from the kitchen with the two sisters, the one who played the piano and the little one with the braces, only she wasn’t little now and the braces were gone.

Mary came in.

She was plumper than Bill remembered, and her hair was cut short and fluffy around her face instead of long over her shoulders, but she was still Mary.

She said, “Hi, there, Bill.”

“Hello, Mary.”

Then in the car, she was close and warm beside him.

“Where do you want to go?” he asked.

“There’s a party over at Angie’s. We might go there.” She hesitated. “Or we could go to a movie?”

Bill said, “Let’s skip the party. I’d kind of like to have you to myself this evening.”

Mary said, “All right. I think it will be a stupid party anyway, and the movie’s a good one.”

The movie was terrible. Bill sat stiffly in the cramped seat, conscious of Mary’s presence beside him. He could smell her perfume and feel the warmth of her shoulder pressed against his. Finally he stopped all pretense of watching the screen and shifted his full gaze to her and saw that she was crying because the woman in the movie could not make up her mind between the two men.

Bill felt embarrassed. He had forgotten how Mary cried in movies. Before he had always teased her about it and found it strangely touching. Now, suddenly, it was ridiculous.

“Come on, Mary,” he said, “let’s go.”

“This isn’t where we came in!”

“We’ll see it some other time.”

He got up and made his way between the sets to the exit. Mary followed him, pouting.

“Bill, I don’t understand what’s the matter with you.”

“I don’t know either,” he said apologetically. “I’m sorry. The movie was getting on my nerves, and I wanted to go somewhere quiet where I could just sit and talk to you for a while. I guess I can stand the rest of it, though, if you want to go back in.”

Mary sighed.

“No,” she said. “Let’s do what you want to do tonight.”

They got into the car.

He said, “Tonight’s the first time I’ve driven a car for six months.”

“What was the last time?”

“It was a Jeep, and I didn’t drive it very far.”

He drove out along the river road to their old parking place by the water, but when he reached it there were two cars already there. He swore a little under his breath and stepped on the gas.

A side road loomed up on his left. He slowed down, turned the car into it and stopped.

The wind came up from the river and breathed through the car windows, soft and cool.

“Thanks for writing so much,” Bill said at last to break the silence.

Mary said, “You hardly wrote at all.”

“I know. I didn’t have time.”

“I didn’t either,” Mary said. “It’s hard to do all the things you really have to do in college, much less write letters. But I made time for that.”

“It was swell,” Bill said. His voice was strained.

What’s the matter with me? he asked himself angrily. I’ve been away two years, and now I’m with my girl and there’s nothing to say!

Always before there had been too much to say, things that would not go into letters when he sat down to write them. He would get as far as Dear Mary, and the paper would stare up at him, white and empty, and the things he wanted to tell her would not be written down. Instead he would say, There have been some men sick, but never how they looked with the sickness and how they smelled and how he felt when he saw them; or, A man was shot yesterday, but never a description of a man with half of his face missing, a man who used to chew gum and play a guitar. He did not write, I’m lonely. I’m sick. I’m scared. Those were things he whispered to Mary in the secret night and saved to tell Mary when he got home and they were together.

Now he took a deep breath.

“Mary,” he said, “I killed a man.”

He waited for her to shiver, to gasp, to be horrified. He waited for the tears that came so easily at a movie.

Instead she said, “I guess everybody did, didn’t they?”

“I don’t know,” Bill said. “I guess they did.”

He wanted her to share the horror of it, and in that way perhaps the horror would go away.

“After all,” Mary said, “that’s what you were there for, to protect our country.”

“But he was a man,” Bill said, “and I killed him. He was a live man, and now he isn’t alive.”

He shuddered and the old familiar sickness went through him.

“Bill,” Mary said suddenly, “have you met another girl?”

“What?”

“I said, is there another girl?”

For a moment Bill was sure that she was joking, but then he realized that he was not.

“No,” he said. “There’s no other girl. How on earth could I have met another girl?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “It’s just that you’re acting so odd. I thought maybe you had met someone else.”

“No,” Bill said again. “There’s nobody but you.”

He put his arms around her and pulled her to him and kissed her. When he kissed her the strain went away and the years between them were gone; it was the night of the Senior Prom, and he was very young and in love. He lifted his face and pressed it against her hair, and for a moment he was filled with peace. He was home and everything was all right.

“Mary,” he whispered, “oh, honey, I missed you so!”

“I missed you too, Bill.”

“Mary,” he said, “let’s get married. Let’s get married now.”

He could feel her start.

“Get married?”

“We’d have the rest of this leave together before I have to go back. Please, Mary!”

She pulled away from him and looked at his serious face.

“Bill,” she said nervously, “Don’t be silly. I couldn’t stop college and get married now. Daddy would have a fit if I even suggested such a thing. And what good would it do? You’d be away all the time.”

Bill released her and leaned back against the seat.

“Yes,” he said wearily, “of course, you’re right. It would be a nutty thing to do. It’s just that you’d belong to me then, and I’d belong to you. Right now I don’t feel like I belong anywhere. Everything’s so different from when I left.”

“I’m not different,” Mary said.

“Yes, you are. We used to not even have to talk, we understood each other so well. Now it’s like we didn’t know each other at all.”

“You do have another girl,” Mary said miserably. “I can tell.”

This time Bill did not try to deny it. He started the motor.

“It’s getting late,” he said. “I’d better take you home.”

When they reached the house Mary opened the car door and started across the lawn.

“It’s all right,” she said, “I can walk to the door by myself.”

“Mary!” Bill caught her.

She stopped and turned back to him; there was no anger in her face, only unhappiness.

“Mary, there isn’t any girl!”

Mary said, “I know there isn’t any other girl. I almost wish there were. At least then we’d know what was wrong!”

Bill stood in the yard and watched the hall light go off and later a light go on upstairs. Then he got back into the car. He started it and pressed the accelerator to the floor and watched the needle creep up across the speedometer. He drove out along the river road again, faster and faster until the sound of the wind past the window was a dull roar. He had driven like this once before, in a Jeep, but suddenly the road had ended and the Jeep had gone off into the underbrush where a man was sleeping. Bill and the man had stared into each other faces, and the man had groped in the bush beside him for his gun, and Bill had picked up his bayonet …

Bill slowed down and drove quietly back to town. He drove home, because there was no place else to go.

He crossed the yard and went up the porch steps and opened the door. It was like going into a stranger’s house, a house that was oddly familiar as from a dream, but not a place where he himself had lived. In his mind were other houses, tumbled masses of houses without walls and without roofs and with all their life gone from them. He stepped into the hall and closed the door behind him, but he could not shut the ghost houses out.

The light was on in the living room. His mother looked up when he came in.

“There’s a piece of cake for you in the kitchen.”

He hesitated.

“Were you waiting up for me?”

“Yes,” his mother said. “I know it’s silly, but I couldn’t sleep until I knew you were in.”

Bill thought, how old she looks! Why, Dad and I always used to think she was the prettiest lady in town!

“It hasn’t been easy with Dad gone, has it, Mom?”

It did not sound the way he had meant it to sound.

She said, “No, dear, it hasn’t been easy. But we’re getting along.”

He wanted to go to her and put his arms around her in a protective gesture, the way his father would have, the way he himself would have so short a time ago. He wanted to say, “Oh, Mother, I’m glad to be back!” He wanted to hug her and say, “Mother, you’re still the prettiest lady in town!” But the shadows of the past two years were all about him, close and real and a part of him.

He looked at his mother, and they could not reach each other.

He said, “Mom, have I changed so very much?”

“It’s the war, Bill,” she said slowly, carefully. “War makes boys grow up too fast. It turns them into men before they are ready and teaches them things they should never know.”

“But why?” he demanded unreasonably. “Why? What’s the matter with me? What in God’s name has happened to me?”

His mother was startled by his outburst.

“Don’t look that way, Bill! Everything will be all right, dear. Just give it time and everything will be all right.”

He hadn’t cried much when he was a child. Now, when he cried, it was the way a man cries when he is lost and afraid.

“Mother,” he sobbed, “oh, Mother, I want to come home!”

She went to him and put her arms around him the way one comforts a child. But he was no longer a child.

“There, there, son,” she said helplessly. “You are home.”

She went out to the kitchen to get his piece of cake.

(written at the age of 18)

First Place Winner in Seventeen Magazine’s

Creative Writing Contest, 1953

What was it about this story that caused it to win a national award?

I wish I knew. I have a feeling there was some reason other than the quality of the writing. Perhaps it stood out from the competition because of the male viewpoint and therefore got an especially careful reading. Perhaps one of the judges had a son in the service. Perhaps the story seemed more important because it was about war and death instead of proms and parties.

Perhaps it was the ending. The ending doesn’t follow the rules of plotting that most youth publications of that day adhered to. It differed from “Written in the Stars” in that I did not have an all-wise mother solve the problem, because the problem is unsolvable. The mother’s pathetic token gesture of bringing in a piece of cake is symbolic of the futility of any loving woman’s efforts to undo the emotional damage done to her son by war. If this story had been submitted by an adult writer, I doubt that Seventeen would have bought and published it. They would have thought it too depressing for their vulnerable young readers. The fact that it was one of those vulnerable readers who wrote the story altered the situation.

I named the young man in the story Bill, not because it was my brother’s name (which it was), but because it was solid, down-to-earth and all-American. The Bill in the story had no personality quirks to set him apart from the rest of humanity.

He was Every Man.