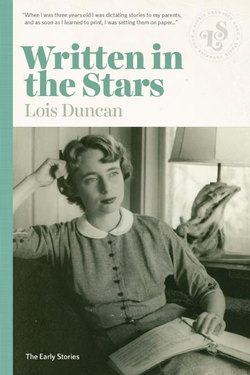

Читать книгу Written in the Stars - Lois Duncan - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWritten in the Stars

Ever since I was very little, I knew that someday my prince would come. At first I used to envision him riding up on a snow-white horse to scoop me up and carry me away to his castle. This changed, of course, as I grew older and my reading matter progressed from Grimm’s Fairy Tales to Romeo and Juliet. I did away with the horse by the time I was eleven, but the rest of the belief remained, a quiet certainty deep inside of me. Somewhere in the world there was The One, the special One, looking for me just as I was looking for him, and someday he would come. It was written in the stars.

I never talked about it much, except once in a while to Mother. I dated just as the other girls did, strings of silly, uninteresting boys, just to kill time until The One arrived. And then, when I was seventeen, two things happened. Mother gave me the locket, and I realized who The One was. Ted Bennington.

When I opened the little white package on my seventeenth birthday and saw the locket, I was flabbergasted. The locket was not a new purchase; I had seen it often before. In fact, every time I rummaged through Mother’s jewelry box to borrow a pair of earrings or a bracelet or something, I saw it, not in the jumble of everyday jewelry but in the separate little tray where she kept all the things Daddy had given her. There was the whole story of a romance in that tray—Daddy’s track medals from college and his fraternity pin, the pearls he gave Mother on their wedding day and the silver pin from their fifteenth anniversary and the silver bars he wore when he was in the Navy during the war. And in the midst of all those things was the locket.

“But, Mother,” I protested, holding it up in amazement, “you can’t really mean for me to have this! It’s yours! It belongs to you!”

“Indeed I do,” Mother said decidedly. “It represents a lot to me, honey. I’ve always said that my daughter would have it when she turned seventeen.” There was a faraway look in her eyes.

“But why seventeen?” I asked. “That’s hardly a milestone like sweet sixteen or eighteen or twenty-one. Seventeen really isn’t anything.”

“It was to me,” Mother said. “It was the age of heartbreak.”

I stared at her in disbelief. “Your heart was never broken!”

It was impossible to imagine Daddy, with his warm gray eyes and gentle smile, ever breaking anyone’s heart, least of all Mother’s. Mother and Daddy had one of the best marriages I had ever known. They always seemed to have fun together, no matter where they were or what they were doing. And they loved each other. You could tell it just by being around them. It wasn’t the grabbing, hanging onto sort of love that kids our age experienced, it went deeper; it was the sort of love that made Mother say two years ago when Daddy died, “Well, I’ve had more happiness in my eighteen years of marriage than most women have in fifty.”

“Oh, it was broken, all right,” Mother said lightly. “And yours will be too, dear. It’s inevitable.” Then she kissed me.

I laughed, a little embarrassed, because we’re not usually a very demonstrative family. Besides, I wasn’t quite sure what Mother was talking about. But I did love the locket. It was tiny and heart-shaped on a thin gold chain, and it was delicate and old-fashioned and lovely. I felt about it the way Mother did about her engagement ring—“Much too valuable just to wear around.” I wrapped it in tissue paper and put it in the corner of my top bureau drawer.

The locket wasn’t the only present I received on my seventeenth birthday. Besides that, Mother gave me an evening dress, ankle length, dark rose taffeta, and Nancy, my best friend, gave me the rose slippers to wear with it. But the gift that topped everything, that caused my stomach to lurch and my heart to beat faster, was a simple blue scarf with a gold border. It came from Ted Bennington.

“I hope you like it,” he said awkwardly. “I didn’t know. I haven’t had much experience picking things out for girls.”

“I love it,” I assured him. “It’s just beautiful.”

I suppressed a desire to lean over and kiss him. It would have been so easy to do because I liked him so much. I liked the way his blond, curly hair fell forward over his forehead, and his honest blue eyes and nice square chin. And I liked his being shy and sweet and serious and a little awkward; it was so different from the smooth know-it-alls in our senior class. I thought, I would like to kiss you, Ted Bennington. But I didn’t say it. And I didn’t kiss him.

Instead I reached over and squeezed his hand and smiled at him and said, “It’s beautiful,” again. Which must have been the right thing to do, because he squeezed my hand and smiled back at me.

I had begun dating Ted a couple of months before that. It was funny how it started. Ted must have been in my class for years and years, and I never really noticed him. In fact, nobody noticed him. He was a quiet boy and he wasn’t on any of the teams or in the student government or in any of the clubs; he worked after school and on weekends in Parks Drug Store. I think that might have been one of the things that made him shy, having to work when the other kids goofed around. “It made me feel funny,” he told me later, “having to serve Cokes and malts and things to the kids and then seeing them in school the next day. You can’t actually be buddies with people who leave you ten-cent tips.”

“But none of the other kids felt like that,” I told him. “They never gave it a moment’s thought. They would have been glad to be friends anytime if you’d acted like you wanted to.”

“I know that now,” Ted said. “But it took you to show me.”

Which was true. It was cold-blooded in a way. I didn’t have a date to the Homecoming Dance and was on the lookout for someone to take me. You don’t have too much choice when you’re a senior and most of the senior boys are going steady with juniors and sophomores. So I made a mental list of the boys who were left and crossed off the ones who were too short, and that left four. Ronny Brice weighs three hundred pounds, and Steven Porter can’t stand me, and Stanley Pierce spits when he talks. Which left Ted.

“Do you know if Ted Bennington’s asked anyone to Homecoming?” I asked Nancy.

Nancy gave me a surprised look. “Who?”

“Ted Bennington,” I said. “The blond boy in our English class. The quiet one.”

“Oh,” Nancy said. “I didn’t know that was his name. No, I don’t suppose he has. He doesn’t date, does he? I’ve never seen him at any of the dances.”

“No,” I said. “I suppose he doesn’t. But there’s always a first time.”

The next morning I got to English class early and as Ted came in I gave him a real once-over. I was surprised. There was nothing wrong with his looks. He wasn’t awfully tall, but he had a nice build and good features and an honest, clean-cut look about him. I even liked the back of his neck.

Ted Bennington, I thought, you may not know it now, but you are going to take me to the Homecoming Dance.

And I managed it. It is a little shameful to me now to think about how calculating I was—a smile here, a sideways look there, “Hi, Ted,” ever time I passed him in the hall. “Which chapters did she say we were to read tonight, Ted?” as we left class and happened to reach the door together. A week or two of that and then the big step. “Nancy’s having a party this weekend, Ted. A girl-ask-boy affair. Would you like to go?” It was really pretty easy.

Ted was standing at his locker when I asked him. He had the locker door open and was fishing out his gym shorts, and when he turned he looked surprised, as though he wasn’t sure he had heard me correctly.

“Go? You mean, with you?”

“Yes.”

“Why—why, sure. Thanks. I’d like to.” He looked terribly pleased and a little embarrassed, as if he had never taken a girl anywhere in his entire life.

“What night is the party?” he asked now. “And what time? And where do you live?”

We stood there a few minutes, exchanging the routine information, and I began to wonder if maybe I was making a mistake asking Ted to the party, to that particular party anyway, because it would be The Crowd, the school leaders, the group I had run around with since kindergarten days. And Ted wasn’t one of them.

But it was too late then to uninvite him, so I let it go, trying not to worry too much as the week drew to a close, and on Saturday night at eight sharp Ted arrived at my house.

He made a good impression on Mother. I could see that right away. He had that air of formal politeness that parents like. When we left, Mother said, “Have fun, kids,” and didn’t ask, “What time will the party be over?” which is how I always could tell whether she approved of my dates.

Ted didn’t have a car, so we walked to Nancy’s, and it was a nice walk. Everything went off well at the party too. The Crowd seemed surprised to see Ted at first, but they accepted him more easily than I had thought possible. Ted relaxed after the first few minutes and made a real effort to fit in; he danced and took part in the games and talked to people.

Even Nancy was surprised.

“You know,” she said when we were out in the kitchen together getting the soft drinks out of the refrigerator, “that Ted Bennington—he’s really a very nice guy. How come we’ve overlooked him before this?”

I said, “I don’t know.” I was wondering the same thing.

I wondered it even more as we walked home afterward, talking about the party and school and what we were going to do after we graduated, comfortable talk as if we’d known each other forever. I told Ted I was going to secretarial school, and he told me he was working toward a scholarship to Tulane where he wanted to study medicine. I learned that his mother was a widow, as mine was, and that he had three sisters, and that he played the guitar. The moonlight slanted down through the branches of the trees that lined the street, making splotches of light and shadow along the sidewalk, and the air was crisp with autumn, and I was very conscious of my hand, small and empty, swinging along beside me. His hand was swinging too, and after a while they sort of bumped into each other. We walked the rest of the way without saying much, just holding hands and walking through the patches of moonlight.

The next morning Nancy phoned to ask if Ted had invited me to Homecoming.

“To Homecoming? Why, no,” I said. And to my amazement I realized that I had completely forgotten about Homecoming—that, now, somehow, it didn’t matter very much.

When the time came, of course, we did go, but, now that I think back on it, I don’t think Ted ever did actually ask me. We just went, quite naturally, because by then we went everywhere together.

When did I realize that he was The One? I’m trying hard to remember. I guess there was no special time that the realization came. It just grew, a quiet knowledge deep inside me. It grew out of our walks together, long hikes through the autumn woods with the trees blowing wild and red and gold against the deep blue of the sky, and the winter picnics with The Crowd, sitting on blankets around a fire with snow piled behind us and Ted’s arm around my shoulders. He brought his guitar sometimes to those, and we all sang.

“Why didn’t you tell us you played the guitar?” somebody asked him, and Ted grinned sheepishly and said, “I didn’t know that anybody would be interested.”

It grew, the realization, through the long lovely spring days and easy talk and laughter and a feeling of companionship I had never known before with any boy or, for that matter, with any girl, even Nancy. One Sunday evening (we had been to church together that morning and to the beach all afternoon and to an early movie after dinner), Ted said, “We fit so well together, you and I,” and I said, “Yes,” and Ted said, “It’s as if it were meant to be that way.”

“You mean,” I said, and the words came haltingly to my tongue because I had never said them aloud to him before and I was afraid they would sound silly, “You mean, as though it were written in the stars?”

Ted was silent a moment and then he said, “Yes, I guess that’s what I mean.”

It was the night of the Senior Prom that Ted saw the locket. As I said before, I didn’t wear it often, it was too precious, but somehow the night of the Senior Prom seemed right. I wore my rose evening dress and my rose slippers and no jewelry except the locket on its slender gold chain.

Ted noticed it right away.

“Nice,” he commented. “Makes you look sort of sweet and old-fashioned. Is it a family heirloom?”

“You could say that,” I said. “Daddy gave it to Mother, and Mother gave it to me.” I touched it fondly.

Ted was interested. “Does it open?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

“Let’s see.” He reached over and took the locket in his hands, the gentle, capable hands I had grown to know so well, and fiddled with it for a moment, and it fell open on his palm, disclosing a tiny lock of hair.

“So!” he said, smiling. “I didn’t know your father had red hair.”

“I guess he must have when he was young. He got gray very early.” I smiled too. “Put it back, Ted. It belongs there.”

He did so, closing the locket gently as though anything that had meaning for me had meaning for him also.

I’d tell you about the summer, but it is too hard to describe. I think you must already know what it’s like to be in love. You get up in the morning and shower and dress and eat breakfast just as you always have, but ever motion, every ordinary thing, is flavored with excitement. “I’m going to see him today—in two hours—one hour—ten minutes—and now he is here!”—there’s a radiance, a silent singing inside you that seems to expand to fill your life. That was the summer—and then, so terribly soon, it was autumn again.

Ted got his scholarship. His face, when he told me, was shining with excitement.

“How do you like the sound of it—Doctor Bennington!”

“Wonderful,” I said. “Marvelous! But I’ll miss you.”

“I’ll miss you too.” He sobered. “I’ll be home on vacations.”

“Sure,” I said. The summer lay golden and glorious behind us; there would be other summers.

“I wish—” His voice trembled slightly. “I wish you were going to Tulane too.”

“I’ll be here for you to come back to,” I said. “I’ll be a secretary in a year, you know. Maybe I can come there and get a job that has some connection with the college.”

“That would be great.” Still he did not smile. “I’m afraid,” he said suddenly.

“Afraid of what?”

“Of going. Of leaving you here. I’m afraid something will happen, that you’ll meet somebody else or something. What we’ve got—it’s so right—so perfect! We can’t lose it!”

“We won’t,” I said with confidence. You don’t lose something that is written in the stars.

And so my prince rode away on his snow-white horse, and that was the beginning of the end. We did not marry. If we had, I wouldn’t bother telling this story. Ted went to college and I to secretarial school, and we wrote letters at first constantly, and then not quite so often. Ted couldn’t afford to come home at Thanksgiving, and when he did come at Christmas I had the measles, (horrible thing to have when you’re practically grown), and we did not really get to see each other until spring vacation. By then we had been so long apart that we spent the whole vacation getting re-acquainted, and then it was time for Ted to go back again. He was as sweet and wonderful as ever, you understand; we just felt as though we didn’t know each other quite so well.

“Don’t forget me,” he said a little desperately as he left.

And I said, “Of course not,” but this time I did not sound so certain.

As it turned out, it was Ted who met somebody else; he who had been so worried, when I had been so sure! But in the end it was Ted who wrote the letter. The girl, he said, was a premed student just as he was. Her name—well, I’ve forgotten her name—but she was small, he said, and had hazel eyes and was smart and fun and easy to talk to. I would like her, he said. We were alike in many ways. He said he was sorry.

It was raining the day the letter came. I read it in the living room and then gave it to Mother to read and went upstairs to my room.

I lay on the bed and listened to the sound of the rain and thought how strange it was, how unbelievable. I didn’t hate Ted; you don’t hate somebody as sweet as Ted. I didn’t even hate the girl. I was too numb to feel anything; I didn’t even cry. I just lay there listening to the rain and thinking, he was The One—we were right—we fitted—we were perfect. Now he is gone and he was The One, and he will never come again.

I was still lying there when Mother came in. She did not knock, she just opened the door and came in and stood by the bed looking down at me. Before she said it, I knew what she was going to say.

“There will be other boys,” she said. “You may not believe it now, but there will be.”

“Yes,” I replied. “I suppose so.” There was no use arguing about something like that. “Ted was The One,” I said. “There will be other boys, sure, but he was The One.”

Mother was silent a moment. Then she said, “Do you still have the locket?”

“The locket?” I was surprised at the question. “Yes, of course. It’s in my top drawer.”

Mother went over to the bureau and opened the drawer. She took out the locket and brought it over to the bed.

“Put it on,” she said.

“Now?” I was more surprised. “But, why? Why now?”

“Because,” Mother said quietly, “this is why I gave it to you.” She put the locket in my hands and sat down on the edge of the bed, watching me as I raised it and put the chain around my neck and fumbled the tiny clasp into place. “You see,” she said when I had finished, “that locket was given to me by The One on the evening of our engagement. We were very young, and he couldn’t afford a ring yet. The locket had been in his family for a very long time.”

“Oh.” I reached up and touched the locket, feeling a new reverence for it. I thought of Daddy drawing it from his pocket, nervous, excited, watching Mother’s face as he did so, hoping desperately that she would like it. Mother and Daddy—young and newly in love, two people I had never known and would never know.

“He was everything,” Mother continued, “that I ever wanted in a husband. He was good and strong and honest, he was tender, he was fun to be with, and he loved me with all his heart. He was without doubt written for me in the stars.” She paused and then said, “He was killed in a train wreck three weeks later.”

“He what!” I regarded her with bewilderment. “But you said—I thought—” I realized suddenly what she was telling me. “You mean it wasn’t Daddy? You loved somebody before Daddy, somebody you thought was The One, and then—”

“I didn’t just think it,” Mother interrupted. “If I had married him I’m sure I would have been a happy woman and loved him all my life. As it worked out, three years later I married your father, and I have been a happy woman and loved him all my life. What I am trying to tell you, honey”—she leaned forward, searching for just the right words—“There is no One. There are men and there are women. There are many fine men who can give you love and happiness. Ted was probably one of those, but Ted came into your life too soon.”

“But,” I protested weakly, “that’s so cold-blooded, so sort of—of—” I felt as though I were losing the prince on the snow-white horse, the dream that was bright with the wonder of childhood.

“I’m saying,” Mother said gently, “that there are many men worthy of loving. And the one of those who comes along at the right time—he is the One who is written for you in the stars.”

She went out then and closed the door and left me alone, listening to the rain and fingering the locket. I stared at the door that Mother had just closed behind her.

And then I began thinking of the other door, the one she had just opened.

(written at the age of 20)

I was married two days after my nineteenth birthday, at the end of my freshman year of college. During that year I had fallen in love with a senior, who now was graduating and joining the Air Force. I was frightened that being apart might mean the end of our relationship, so when he proposed, I said yes.

It was an unwise marriage and lasted only nine years.

I wrote this story one year after our wedding, at a time when I still was telling myself I was happy.

When writing it, I drew upon fragments of past experiences: my gentle romance with a sweet, shy boy in high school; a story my mother had told me about her first fiancé who was killed in a train wreck; an experience one of my friends had had when she and her high school boyfriend attended different colleges.

That was all this story was supposed to be.

When I read it now, however, I find something in it that I do not think I meant to put there. Was it possible that already I was starting to question, without allowing myself to realize it, the rightness of that step I had taken so hastily? If I had waited until I was wiser, more experienced, more mature, might I have chosen differently?

Was this handsome young man, with whom I was starting to discover I had little in common, truly The One who was written for me in the stars?